Matt Duffin’s paintings aren’t what you’d call cheery—but who wants Disney these days with the sky falling around our heads? Anxiety and dread, and perhaps hope, are the keywords for today, and Duffin’s paintings in encaustic wax reach them directly, amplifying what we thought were private feelings.

Duffin was born in 1968 and grew up in Houston. He studied architecture, but never practiced as an architect. He has lived in Spain, Costa Rica, and Taos, N.M., and currently resides in northern California with his wife and two small children. All images copyright © Matt Duffin, all rights reserved.

Where do the images start?

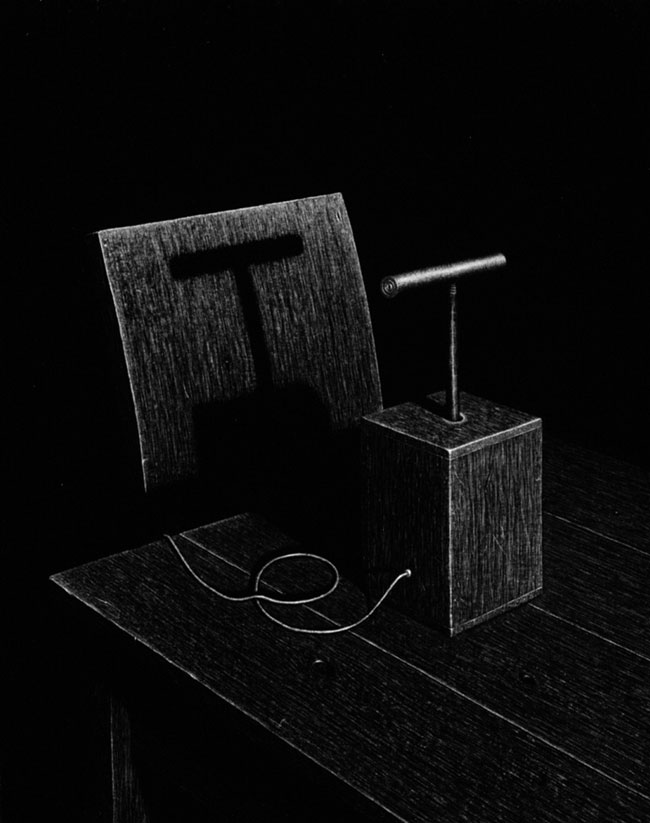

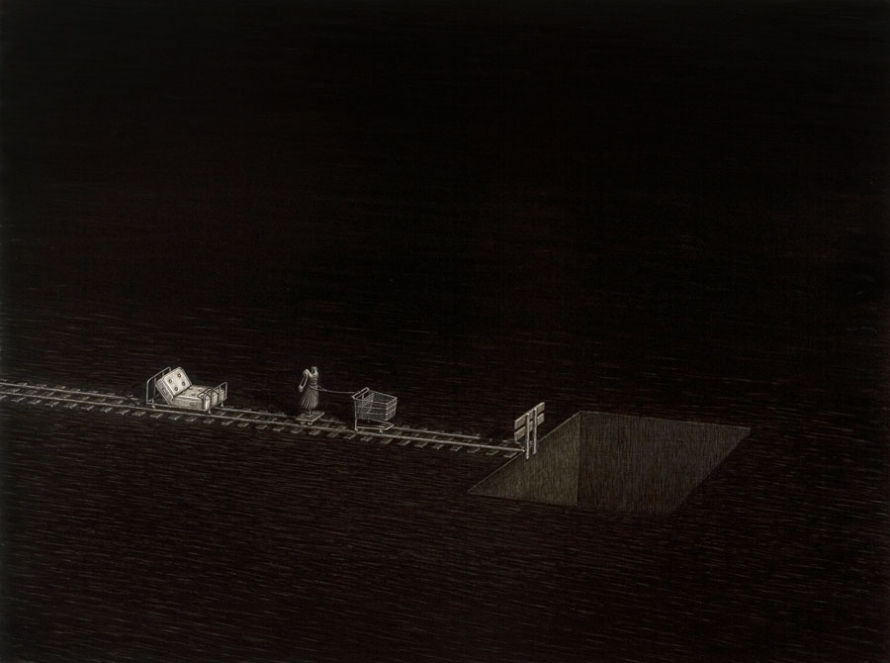

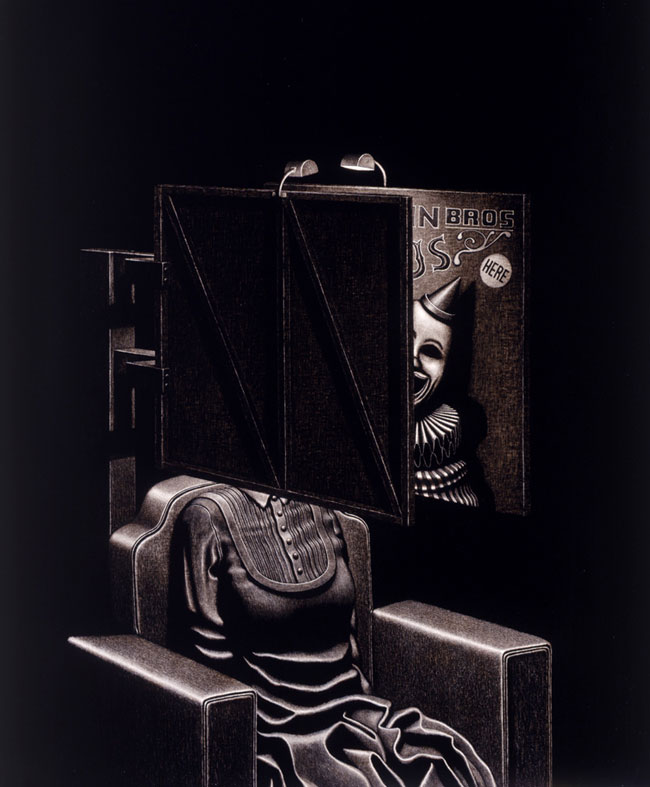

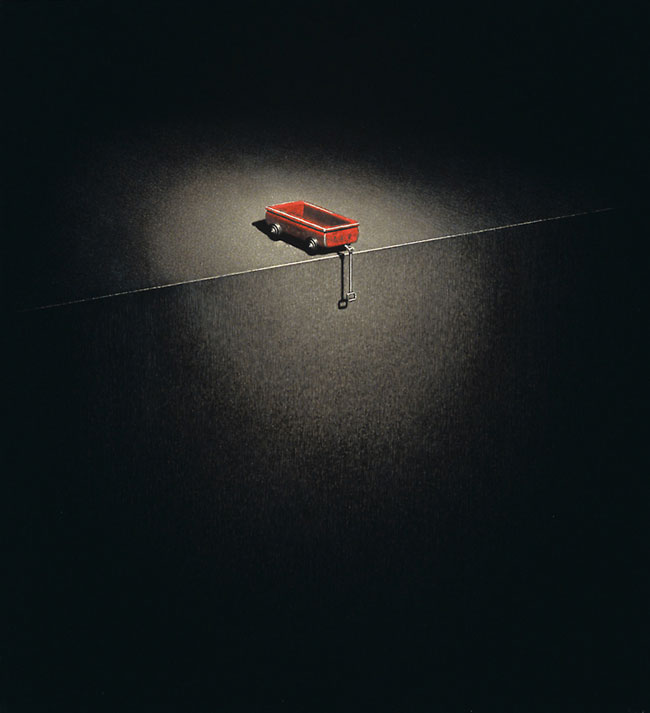

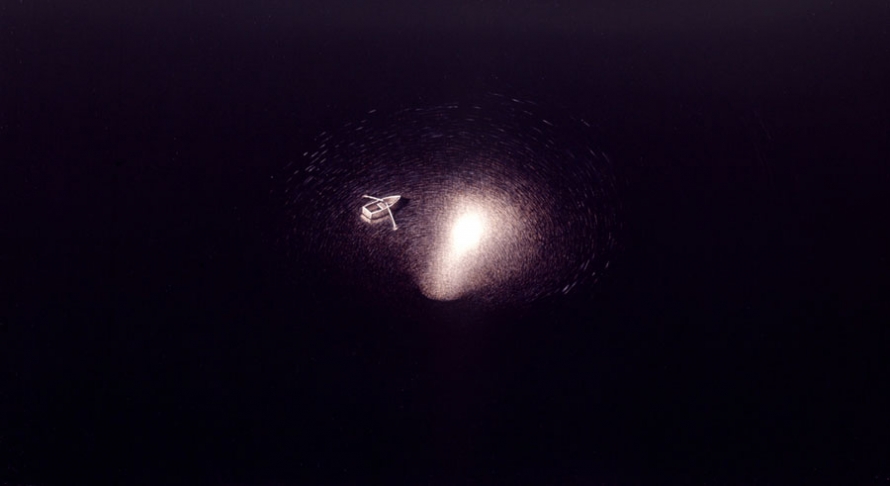

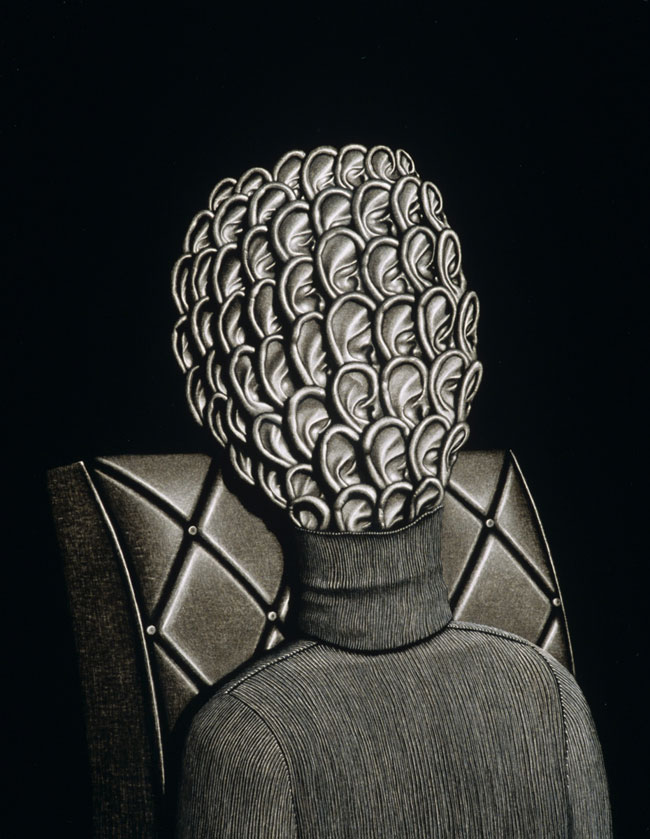

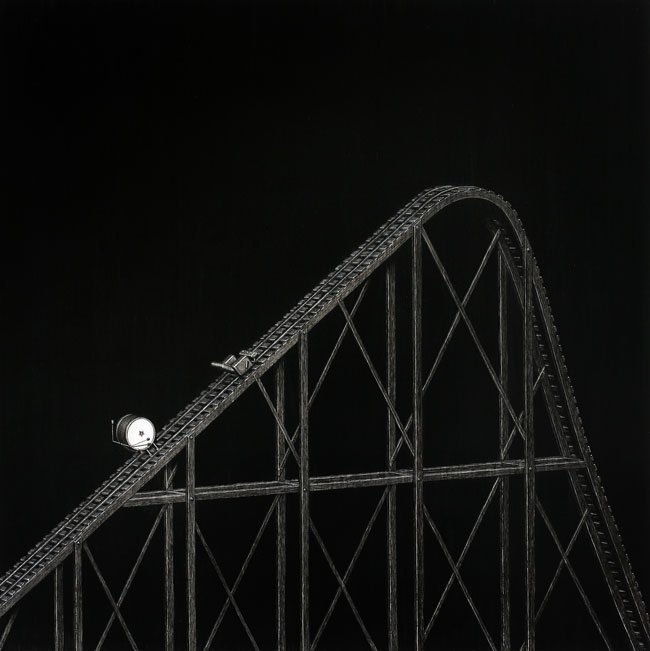

My process stems from a fascination that I have with darkness and the myriad feelings that it evokes—melancholy, tranquility, mystery. I always start with this as a backdrop. I sketch an idea that plays on these feelings, often throw in a bit of black humor, and then try to execute it in the wax. Once I’m working with the wax, literally scratching out the idea I’ve chosen to work with, those feelings and the space I’m creating almost become real to me. In a way, I’m sort of pulled into the painting like a writer getting sucked into the story he’s weaving. It’s just that in my story the characters are the objects in the painting—the balloons, the chairs, the doors, and the rooms. It’s akin to daydreaming.

What is encaustic wax anyway?

Encaustic wax is a medium that’s been around for a really long time. It was fairly ubiquitous in Greek and Roman painting and sculpture. It wallowed in obscurity until the early 20th century, when it was revived by artists such as Diego Rivera, Robert Delauney, and eventually Jasper Johns. But because it’s a wax-based medium, the artist has always had to contend with the problem of melting it to be able to work with it. It really wasn’t until the advent of portable electric heating devices that it was accepted as a viable artists’ medium.

Historically, encaustic wax was a haphazard mix of vegetable, mineral, and even insect waxes, combined with oil or resin and solvents such as turpentine, which often made it unsafe to work with. Modern encaustic wax has eliminated the need for harsh solvents and is comprised of beeswax, Damar resin, and finely-milled pigments. While it’s possible for the artist to make his or her own encaustic paint, the process is laborious and complicated. I leave all the wax-making to a small company in the Hudson River Valley in New York called R&F Paints. The owner, Richard Frumess, worked for Torch Art Supply, the small art store in New York City that in the ‘40s was the first to make ready-made encaustic paint available to the public. When Torch went out of business in the late ‘80s, Frumess formed R&F and spent years refining the production techniques and expanding the color line.

How did you progress to wax?

I stumbled onto encaustic wax after years of experimentation and discovery with other mediums. Like most artists, I started out with a pencil and sketchpad. I graduated to progressively darker, richer mediums, but always stuck with black and white because it spoke to me more than color. And because I went to architecture school, where the black-ink pen was king, I never saw the need to learn color theory or even the color wheel, for that matter.

After architecture school, I spent a decade exploring lead pencils, graphite, grease pencils, shoe polish—whatever gave me the richest, most saturated black. I eventually settled on black encaustic wax. The rich, dark, luminous quality of the wax pulls the viewer into the painting moreso than say, a flat watercolor does.

There’s a lot of narrative in each picture, and irony and black humor, but also something childlike or remembered.

My kids are wholly responsible for the childlike quality of some of my work. There is a residual personality that lingers in a space well after they have left it. The toys, the scattered pots and pans, the chair that was brought to a spot to give them access to a previously unreachable cabinet all take on a life of their own after my kids have fled the scene. It would be a dream come true for a detective, were he to have to solve the crime. It’s almost eerily suggestive of something otherworldly, where everything comes to life while no one’s looking.

Charles Addams comes to mind. Is humor harder or easier to capture than other human qualities?

Humor allows me to almost excuse myself of the responsibility of creating “important” work. Because I didn’t go to art school, I’ve always had the sense that I missed out on learning what it means to make important art. I’m constantly haunted by the notion that there are important precepts, or conditions, that I’m supposed to abide by, but can’t, because I don’t know what they are. This is compounded by the fact that I’m fairly out to lunch when it comes to art history, especially with regard to specific artists. Like everybody else, I know Warhol, Pollack, Magritte, etc., but even my kids know more about everybody in between. So by relying on humor as a main ingredient in my work, I find that I am given a free pass of sorts. Visual humor is a universal language—everybody gets it. No matter what your level of schooling with regard to art, the only thing that matters when the art is about humor is whether or not the piece is funny. If it accomplishes that goal, then it is successful. Maybe not in landing itself in history books, but in moving the viewer in such a way that he or she connects with the work. And in using black humor, the target audience is narrowed to that slice of society that is cynical and jaded enough to know that however jolly and good things are, the end is the same for all of us- the ineffable abyss of eternal nothingness.

I think a comparison with Chas Addams is quite a compliment, but don’t quite know if I’m worthy of it. He was a master of that kind of humor.

What about anxiety?

Anxiety is perhaps the only human emotion, or quality rather, that I find easier to capture in my work than humor. While it’s a challenge to successfully skirt the very thin line between funny and corny, there is no risk of failure in conveying what makes me truly anxious. It’s an emotion in which I’m very well versed, a state that I reside in daily. Or perhaps biweekly, depending on the state of the world. In these times, it’s a state from which I find it hard to find refuge. There is no crisis, fear, or potential catastrophe these days that escapes my radar. The risk that I take when basing my work on anxiety is that of unnerving the viewer to such an extent that he or she avoids my work altogether. Unless that person is, of course, as much of a masochist as I am.

Music appears to be a theme—is that something personal?

If you’re referring to the recurrent use of gramophones in my work, they’re very specifically meant to symbolize the relentless and redundant message of fear, punishment, and unquestioned loyalty we’ve all been subjected to for the last eight years. In my work, the recipients of this message are often portrayed by the hapless, obsequious donkey—the Joe the Plumbers out there who need that sort of simple, forceful directive to cling to. The same can be said of anyone who clings to any other dogma of “my way or the highway”—be it religious, philosophical, or political. It’s amazing to me how many people were bullied into accepting that way of thinking during the last two political cycles. I think there has finally been a resounding rejection of that approach, given the results of the last election and the fact that Bush’s recent approval ratings are higher than those of only Truman and Nixon. The fact that change is in the air is a relief to me for more than the obvious reason—the use of that theme in my work was sort of wearing on me.

What are you working on now?

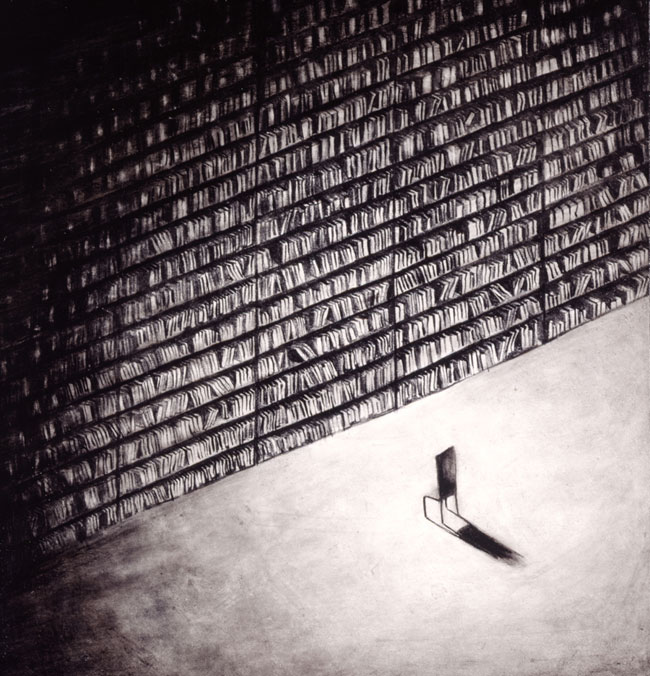

My work has come full circle. When reduced to its purest elements, it’s nothing more than a single object of focus in a sad, lonely, desolate, dark, and impossible place that stretches to infinity in all directions. “The Library” was one of the first pieces I did, and I think it epitomizes that experience. Some of the balloon pieces do, too. My newest work is reminiscent of those origins, only that now the space offers nothing more than a small patch of lighted ground to hold onto—it’s almost the absence of space, eternal darkness. While some people find such a place to be suffocatingly depressing, I find it to be incredibly soothing. Maybe what makes it so peaceful to me is the relief that the enormity and mystery of it are far too big to be figured out, so why bother.