Mammal dads are dicks. Once the heavy breathing is over and the DNA is spilled, they head for the hills.

Oh, there are exceptions. Lions are good dads. And wolves. And marmoset fathers are totally, 100 percent responsible for child care, only bringing in the mom at meal times.

But bears are among the worst. Not only do they not recognize their own offspring, they sometimes eat them. Imagine Papa Bear pushing away his porridge to snack on Baby Bear. Asshole.

Generally, slimy dads are good dads. Male seahorses, catfish, and microhylid frogs all carry their young around till they’re born—their deadbeat mates never send so much as a card.

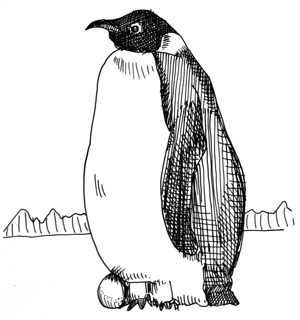

But the “Best Dad” T-shirt goes to a bird.

The Emperor is the largest of the penguins, three or four feet tall, weighing up to 90 pounds. If he doesn’t smoke too much, he could live to see 30. In late summer, these big creatures preen and spoon and then slap on their Barry White albums and get it on. In June, as the long, dark arctic winter is dawning, the female penguin deposits a single perfect egg, the size of a decent ruby grapefruit, there on the sea ice.

The Emperor is the largest of the penguins, three or four feet tall, weighing up to 90 pounds. If he doesn’t smoke too much, he could live to see 30. In late summer, these big creatures preen and spoon and then slap on their Barry White albums and get it on. In June, as the long, dark arctic winter is dawning, the female penguin deposits a single perfect egg, the size of a decent ruby grapefruit, there on the sea ice.

Then she splits for the feeding grounds to gorge on krill and calamari while Dad takes over. Wearing just a feather tuxedo and a bright orange bow tie, he hunkers down over the egg, tucking it between his belly flap and his leathery webbed feet. Like an overdressed Horton the Elephant, he stands there for the rest of the winter, 115 days at 40 degrees below zero. Beyond shifting his weight from foot to foot, he doesn’t budge. Beyond whatever crumbs he may have caught in his bridgework, he doesn’t eat. And then, as spring breaks, so does the egg. The Empress returns to take over the diaper changing and the dad gets to take a break, hit the john, and have a sandwich.

What a guy.

While I admire the Emperor penguin for his commitment, he clearly has issues. When I set out to be a dad, I wanted to be a good one—helpful, present—but not a total control freak.

It was hard to find great examples. My own parents separated months after I was born. My various stepfathers taught me more about what not to be. My friends, by and large, weren’t having kids yet and, being men, didn’t talk about this sort of stuff. I’ve always hated Bill Cosby, Robert Young is dead, and Homer is a cartoon.

Barnes & Noble was full of pregnancy books for women: how to get pregnant, how to stay pregnant, what to eat, what to wear, how to exercise, how to cope, how to scratch your ass; and for men: basically zip.

The few books that were for expectant fathers were full of lame jokes about midnight feedings, stinky diapers, and women’s weirdnesses, but they didn’t tackle the issues I was wrestling with, like, “What the hell do you think you’re doing pretending you’re qualified to be a parent?” and, “Have you seen how many screwed-up, gun-toting kids there are already out there cruising the strip malls of America and now here you come contributing to the problem?” and of course, “Why would you go from being swingingly single or, at worst, part of a couple with plenty of cash and time and beer, to a harried, balding, asshole in a fanny pack yelling at a pack of brats around the entrance to Six Flags?”

Most of the regular women’s books on the subject made patronizing suggestions to include the dad in things like attending office visits, training to be a birthing coach, learning to diaper a rubber doll, but they are as real world as the sex advice in Cosmo. It’s as if the literature of womankind wants to make men feel obligated enough that they can’t sneak out of the room (“Honey, are you listening to this?”) but also as if everyone knows their only contribution consisted of a teaspoon or two of viscous liquid.

So I thought it would be good to document what an engaged, involved, eager-beaver dad could expect, based on my experience, and also to capture some of the issues one considers as the big day approaches: a travel journal of sort, charting the journey from dude to dad. I imagined a hefty trade paperback full of diagrams and charts printed on laminated stock to be wiped free of the inevitable formula and urine spills, a well-thumbed and “beloved classic” that would be the “indispensable companion of every modern father-to-be,” updated every couple of years to include the latest views on how to lay a newborn in its crib, the 10 most popular baby names, how to mix formula with common power tools—in short, “an extraordinary help for the regular guy.”

Instead, I wrote this.

Unfortunately, for you and for me, I’m not regular. Just like the deformed sweaters you find in factory outlets, I’m irregular in just about every way. My advice on what to expect or how to respond is suspect and hard to fit into diagrams.

To compound the problem, pregnancy is not a very regular business either. Sure, it has a standard beginning and just a handful of optional endings. But the trip in between can take many turns and swirl your brain in countless directions.

I’m not much one for sports or sports metaphors, but this being a book about manly things, let me take a stab at one and please be forgiving.

Pregnancy is like golf.

You need at least one ball and a club to start the game and by the end you will be praying and staring at a hole. That’s crude in a stand-up comic kind of way, I know, but that is also the key to its poetry. At the tee, a board announces what constitutes “par,” the standard course of events to come, nine months, four strokes, etc. Invariably, however, things don’t go as planned. There are infinite meddling factors that will extend or contract the outcome, and practice is no guarantee of success. You come clean off the tee, then hook into the rough. You take penalty strokes, lose balls, bury yourself in a bunker, or roll into the drink. You can bogey a hole one day and pull a birdie on the same hole the next. Regardless of whether you take seven months or 10 to finish up, you’ll end up in the clubhouse telling stories about your round and puffing on a cigar.

You need at least one ball and a club to start the game and by the end you will be praying and staring at a hole. That’s crude in a stand-up comic kind of way, I know, but that is also the key to its poetry. At the tee, a board announces what constitutes “par,” the standard course of events to come, nine months, four strokes, etc. Invariably, however, things don’t go as planned. There are infinite meddling factors that will extend or contract the outcome, and practice is no guarantee of success. You come clean off the tee, then hook into the rough. You take penalty strokes, lose balls, bury yourself in a bunker, or roll into the drink. You can bogey a hole one day and pull a birdie on the same hole the next. Regardless of whether you take seven months or 10 to finish up, you’ll end up in the clubhouse telling stories about your round and puffing on a cigar.

My metaphor’s a little tangled, but do heed one point. You, the father, are at best the caddy. Maybe you’ll get to suggest a club now and then, maybe you’ll be asked to estimate the distance to the pin, and if it rains, you will hold the umbrella—and probably not over yourself. So what do caddies think as they trudge behind the players, schlepping the bag? Does anyone care? Maybe that’s why, in trying to write about caddying on one particular round, I ended up having to tell the whole history of the sport since the birth of birth itself.

My Family: A Long, Sexual History

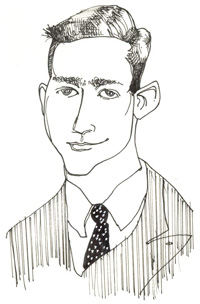

The primal scene. A bed sit near Portobello Road. Recently extinguished cigarettes smoldering in the lid from a marmalade jar. Snow gathering. The ‘60s just beginning. My mother: Pipsi, short for Pippschoen, German for “beautiful little doll.” She has just turned 21, maybe even that day. Nubile, buxom, and ripe. Her hair straightened on coffee cans. Her lipstick pale. Her dress on the floor. My father, Keir: not yet balding. Slim. Slightly manic. Their activity: grunting and commingling DNA.

Rewind.

A whitewashed room in Northern India. A skink crosses a crack in the plaster. The punkah revolves lazily overhead, rippling the mosquito net. Within, two refugees: my grandparents. Ninny has just arrived from Italy via the Suez Canal. She and Gran had been separated for months as he drifted through the government offices of the subcontinent, seeking haven amid a flurry of rubber stamps and carbon paper. Their new marriage has been held together with aerograms and hope. Now, like newly captured animals, they have finally acclimated to their cage. They are safe and ready to breed. They grunt happily between the sheets and the netting.

A whitewashed room in Northern India. A skink crosses a crack in the plaster. The punkah revolves lazily overhead, rippling the mosquito net. Within, two refugees: my grandparents. Ninny has just arrived from Italy via the Suez Canal. She and Gran had been separated for months as he drifted through the government offices of the subcontinent, seeking haven amid a flurry of rubber stamps and carbon paper. Their new marriage has been held together with aerograms and hope. Now, like newly captured animals, they have finally acclimated to their cage. They are safe and ready to breed. They grunt happily between the sheets and the netting.

Rewind.

A shtetl in western Poland. My great-grandparents approach each other from opposite ends of a carved rosewood bedstead. He is equipped only with a spade-shaped black beard, she draped in a sheet with a strategically situated hole. Of all God’s obligations, this is the one to which he is most devoted. In a few years, he will funnel all of his money into a warehouse full of sacks. When he sells them the following week, a gentile will wait two days too long to pay him. Inflation will ravish his investment, leaving him with only a wheelbarrow full of worthless deutsche marks. He will spend it all on two loaves of bread to feed the child he is about to conceive. She mutters a brakhah. He grunts and reaches for the form beyond the holey sheet.

Rewind.

Great5-grandparents grunting in a hayrick.

Rewind.

Great9 grunting in a tent.

Rewind.

Great87 grunting on the veldt.

Rewind.

Great2405 grunting in the primeval swamp.

Rewind…

Ancestry is destiny. All of these contributors to the Peanut’s constitution come from so many places and perspectives, each of them strong and willful, survivors who made it long enough to reproduce.

What chance does the little bugger have against this mountain of history? What choices can the Peanut possibly make in life? Isn’t every attitude, every outcome, preordained?

And what choice do I have in being a father? Aren’t I just doomed to play out my role, to be just a chip off Keir’s block or Gran’s or that of every Chaim Yankel or Clifford Horace that preceded them? I don’t know that there’s a one of them I actually want to closely emulate, but why? Might they all actually have been great parents, great people, leading great23 lives and I just don’t see it? Am I the only freak, the only misfit in an unbroken line of great dads who played catch with their kids, showed them how to harness a mule or spear a mastodon, helped them with their homework and tucked them into bed feeling confident and capable? Am I horribly unfair and judgmental? Am I just cataloging the occasional lapses any parent is capable of, using the distorting lenses of time to turn them into Grave Wrongs, crafting a Dickensian childhood out of an ordinary one?

And what choice do I have in being a father? Aren’t I just doomed to play out my role, to be just a chip off Keir’s block or Gran’s or that of every Chaim Yankel or Clifford Horace that preceded them? I don’t know that there’s a one of them I actually want to closely emulate, but why? Might they all actually have been great parents, great people, leading great23 lives and I just don’t see it? Am I the only freak, the only misfit in an unbroken line of great dads who played catch with their kids, showed them how to harness a mule or spear a mastodon, helped them with their homework and tucked them into bed feeling confident and capable? Am I horribly unfair and judgmental? Am I just cataloging the occasional lapses any parent is capable of, using the distorting lenses of time to turn them into Grave Wrongs, crafting a Dickensian childhood out of an ordinary one?

Am I just as capable of cruel selfishness, of slapping my children with shoes and hairbrushes, of shipping them around the world for years at a time? Am I bound for the same impatience and carelessness, misguidedly thinking I’m doing all I can? Is it all in my head? How did it get there?

Fatherhood: A Résumé

I was a newborn, and my father opened my diaper. As he inspected its contents, I peed full in his face.

I was two, and there was a long staircase that wound down a white cliff. My paternal grandmother, Nana, made me beans on toast and sweet tea. She had a tortoise with a hole drilled in its shell so I could lead it around with a ribbon.

My father had kidnapped me after a fight with Pipsi, convinced that she was nuts and irresponsible, and had hidden me with his own mother at a rented cottage by the sea. Pipsi had no idea where I’d gone until he relented and brought me back—one of their many reconciliations.

I appeared in my mother’s womb when Pipsi was a student at the University of London. She and Keir weren’t married, and he claimed that I was conceived on their first date. They had a tumultuous relationship and Pipsi went to the abortion clinic to get rid of me. In the waiting room, she changed her mind and walked out. They got married five months later. It didn’t last, and they split several times, finally divorcing when I was three or four.

I appeared in my mother’s womb when Pipsi was a student at the University of London. She and Keir weren’t married, and he claimed that I was conceived on their first date. They had a tumultuous relationship and Pipsi went to the abortion clinic to get rid of me. In the waiting room, she changed her mind and walked out. They got married five months later. It didn’t last, and they split several times, finally divorcing when I was three or four.

I have a few eight-millimeter home movies that they made while she was carrying me. They are quite playful and loving, and my mother is very beautiful, like Merle Oberon or a young Elizabeth Taylor. He filmed her pushing an empty pram and dressed as a gypsy, but despite all the larking about, you can feel his need for control. When she films him, Keir is always directing her, telling her when to shut the camera off or to move to a different angle, a tight smile on his face.

My mother’s parents, Gran and Ninny, weren’t very supportive during these squabbles because my father wasn’t a Jew. Keir’s father, an old anti-Semite, was similarly against the union. Still, they all seemed to have loved me, the first child of first children.

Pipsi and I finally fled England when I was four. She set up a ruse, telling Keir that they should take a little time apart and then reunite in Pakistan at my grandparents’ house. However, we went the opposite direction, to Pittsburgh with Bill, a gangly American mathematician who was to be her second husband and to father my half sister, Miranda. When Keir found out he’d been duped, he notified the American immigration authorities that Pipsi was a prostitute and Bill a pimp who’d brought her into the country for depraved purposes. I didn’t see Keir again for a decade.

Pipsi and I finally fled England when I was four. She set up a ruse, telling Keir that they should take a little time apart and then reunite in Pakistan at my grandparents’ house. However, we went the opposite direction, to Pittsburgh with Bill, a gangly American mathematician who was to be her second husband and to father my half sister, Miranda. When Keir found out he’d been duped, he notified the American immigration authorities that Pipsi was a prostitute and Bill a pimp who’d brought her into the country for depraved purposes. I didn’t see Keir again for a decade.

Pittsburgh didn’t keep our interest long. Within a year, we had immigrated to Canberra, where Bill and Pipsi continued their studies at Australian National University.

I was nine and alone in the Bangkok airport with three hours until my connecting flight. Gran had sent me $10 to spend on the trip. I had already bought a glass of 7-Up and some crisps. He had told me there would be men selling battery-operated toys in the airport, specifically, a mechanical bartender that would drink a beer, then roll its eyes and emit green smoke from its ears. “Buy yourself such a toy and bring it with you,” he said in his letter. There were no such men or toys. I bought a second 7-Up, guiltily.

I was nine and alone in the Bangkok airport with three hours until my connecting flight. Gran had sent me $10 to spend on the trip. I had already bought a glass of 7-Up and some crisps. He had told me there would be men selling battery-operated toys in the airport, specifically, a mechanical bartender that would drink a beer, then roll its eyes and emit green smoke from its ears. “Buy yourself such a toy and bring it with you,” he said in his letter. There were no such men or toys. I bought a second 7-Up, guiltily.

Pipsi had just started living with Mike Kahan. Bill had gone, after kicking in the door of her new maroon MGB. Pipsi drove off while Bill hopped around the front yard, clutching his broken toe, and I stood nearby, apologizing. Miranda was still in nappies and Pipsi’s doctoral thesis was still in outline. I was to spend the next 15 months in Pakistan, with my grandparents, while Pipsi finished her work. Then she would come and get me, and we would go somewhere. Meanwhile, the three Ms: my mum, Miranda, and Mike Kahan, would live in Australia. I was on my way to Lahore, 6,709 miles away.

I was 10 and in a bed and breakfast in London. After a year and change in Lahore, Pipsi and posse had shown up to collect me. It wasn’t clear where we were to go next. Australia was no longer the land of opportunity, and so we were exploring. I’m not sure exactly what we were looking for, but the choice had come down to England or Israel.

My mother and Mike Kahan had gone for the evening, leaving Miranda and me in our room. It smelled of dust and cold wallpaper. Miranda was three and asleep. I inched open the creaking door and edged out into the creaking hallway. The creaking staircase was lit with occasional brass sconces and was deserted. I crept down and down, riding the banister, until I came to the lobby. The pub door was ajar and tendrils of cigarette smoke and the barking of adults dribbled through. In a darkened corner around the staircase stood a wooden phone box and when I slid open the creaking door, a light illuminated a pair of hinged directories dangling within. I flipped through the pages and found several pages of Gregorys. There were no Keirs. He was not listed or not living.

My mother and Mike Kahan had gone for the evening, leaving Miranda and me in our room. It smelled of dust and cold wallpaper. Miranda was three and asleep. I inched open the creaking door and edged out into the creaking hallway. The creaking staircase was lit with occasional brass sconces and was deserted. I crept down and down, riding the banister, until I came to the lobby. The pub door was ajar and tendrils of cigarette smoke and the barking of adults dribbled through. In a darkened corner around the staircase stood a wooden phone box and when I slid open the creaking door, a light illuminated a pair of hinged directories dangling within. I flipped through the pages and found several pages of Gregorys. There were no Keirs. He was not listed or not living.

I hadn’t seen my father in many years and I wondered a lot about him. Pipsi painted an attractive picture of him: amusing, eccentric, creative, soulful. I had no memories of him at all.

I was an awkward child, and despite my mother’s efforts, I felt unloved, outside of everything. It seemed to me that my true identity lay elsewhere, that I was meant to a proper British gentleman, dignified, respected, self confident, perhaps a bit of a swashbuckling adventurer. Somehow, it seemed that Keir was my link to that true self. He would ground me and welcome me home to my birthright.

I just couldn’t find him in the London phone book. I ran back upstairs, afraid that Miranda would have woken up.

I was 11, Miranda was five. We were in the backseat of the Saab, driving to Tel Aviv. Mike Kahan explained as he drove, using his fingers to demonstrate.

I was 11, Miranda was five. We were in the backseat of the Saab, driving to Tel Aviv. Mike Kahan explained as he drove, using his fingers to demonstrate.

“You expect me to believe you did that to her?” I said in disgust.

“They must have done it twice,” Miranda piped up. “They have two kids.”

“We’re not their kids,” I said. “Bill’s your dad, and Keir’s my dad, stupid.” I indicated Mike Kahan’s back with my thumb. “He’s not our real father.”

“Do you think you two are ever going to do it?” Miranda asked Pipsi. “Can we watch?”

Pipsi turned up the radio.

I was 13 and standing in front of the congregation of Har El Temple in Detroit. We had been back in America for eight weeks, literally fresh off the boat from Israel. I had studied with a rabbi in our former hometown of Kfar Saba, an hour from Jerusalem, learning the singsong of my haftorah portion. My Hebrew was flawless after six months on a kibbutz and two years in an Israeli public school.

Mike Kahan decided that I should have my bar mitzvah in the same synagogue in which he’d had his two decades before. The various wings of his clan gathered for the occasion, meeting the newest additions. They were all super-sized people who breathed noisily through their noses. Mike Kahan’s mother was froglike with a tight helmet of poodle hair and hands like unpedicured feet. His brothers were lawyers; one would soon run off with a younger woman and then OD on cocaine. The other was in his 20s and his third marriage. The children were all large, football playing boys with stars of David around their necks. They were super-confident, super-fit, with large allowances, trust funds, and cigar boxes full of marijuana.

Mike Kahan decided that I should have my bar mitzvah in the same synagogue in which he’d had his two decades before. The various wings of his clan gathered for the occasion, meeting the newest additions. They were all super-sized people who breathed noisily through their noses. Mike Kahan’s mother was froglike with a tight helmet of poodle hair and hands like unpedicured feet. His brothers were lawyers; one would soon run off with a younger woman and then OD on cocaine. The other was in his 20s and his third marriage. The children were all large, football playing boys with stars of David around their necks. They were super-confident, super-fit, with large allowances, trust funds, and cigar boxes full of marijuana.

I had been nursing a fantasy through the whole process, one inspired by a passing comment Mike Kahan had made when he first talked about coming to Michigan. A friend of his, upon his son’s bar mitzvah, had brought a $500 hooker to the boy’s room after the party and said, “Now you’re really a man.” Somewhere deep down I believed that this was Mike Kahan’s plan, too, and that if I played my part through the ceremony and the reception, he would be doing the same for me. Of course he didn’t. I didn’t get any present from him at all. I asked my mother about it as Mike Kahan pocketed all of the checks his relatives handed me (I netted $1,300 that day but after Mike Kahan “invested” it for me, I never saw a cent).

“Don’t be so ungrateful,” she said. “Do you know how much it’s costing to rent this hall?”

I rattled through my prayers and readings. I was perturbed by the Yiddish pronunciation of the rabbi and the ancients in the congregation, garbling the language I had spoken with my friends for years. I couldn’t stand the way they said R, the way they turned T into S, the incomprehensible emphases they placed.

I wasn’t just a language snob. I was scared by how foreign I felt. Their Hebrew was different than mine, their Judaism was different, even their English was full of words and pronunciation I didn’t understand. My accent, my word choices pegged me as a scrawny foreigner amidst the strapping, milk-fed, straight-toothed, tanned, girl-grabbing, strapping youth of my “family.” By welcoming me into their tribe, into the community, into the country, this group, through no fault of their own and with the best of intentions, had helped me to feel more alienated than ever.

I wasn’t a Kahan. I wasn’t an American. I wasn’t a Jew. I wasn’t a man.

I was still 14, in a bedroom above a pub in Dorset. Keir and I sat on parallel twin beds. My father was crying. I had tracked him down—I can’t remember how, but I’m sure Pipsi helped.

Earlier in the day, he and I had shared a rowboat with his eldest daughter, Tilly. She was three. I had never been in a rowboat before and struggled with the oars. As I flailed, the brass oarlocks slipped out of their moorings and fell, one after another, into the brown canal. I tried to paddle without them, splashing water and moving the portly boat hopelessly in circles. My passengers sat watching me, Tilly stoic, Keir getting angrier and angrier.

Earlier in the day, he and I had shared a rowboat with his eldest daughter, Tilly. She was three. I had never been in a rowboat before and struggled with the oars. As I flailed, the brass oarlocks slipped out of their moorings and fell, one after another, into the brown canal. I tried to paddle without them, splashing water and moving the portly boat hopelessly in circles. My passengers sat watching me, Tilly stoic, Keir getting angrier and angrier.

“Go in and get them,” he yelled.

“I don’t know where they went.”

“They went in the water. Dive in and find them.”

“But I don’t have a swimsuit.”

“I will not have you endangering the life of this child. Get in the water.”

“But I can’t see anything.”

“Feel around for them.”

“It’s very muddy. I can’t feel anything.”

“Get your head under the water.”

“I’m trying.”

“Come on.”

“I can’t find them.”

“Then push the boat. Go on, kick.”

Now, as Tilly and her sister and mum slept at Keir’s brother’s house, my father was crying. He told me how my mother had stolen me when I was little, how he’d felt when I was gone, unable to do anything but drink and paint horrible pictures of my mother being disemboweled and of himself being crucified. He did a lot of beautiful painted scenes of my mother with a big nose, watching him bleed on the cross, often while eating. He told me how he’d looked for me, writing letters to various governments, how he’d finally given up and married Sue.

I felt slightly thrilled to hear his story. He was talking to me like an adult, very frank and self-pitying. He told me he could only think of me as a little boy, just three or four years old. I could only be his son as a memory. He told me he didn’t really care much about how I was now, pubescent, rangy, unhuggable. I wasn’t even English anymore. I talked like a Yank, I couldn’t make a decent cup of tea, couldn’t even row a boat. What had she been teaching me?

I was just a reminder that he was getting old, reminded him of the bad time in his life, of that bitch. He had a new family now, new children, a new and pliable wife, and he was going to make sure that they never went away. Meanwhile, I had my mum and “that Mike” to look after me. That’s just the way that it was.

I was 15 and thin and solitary. I’d never had a girlfriend, never been on a date. A few months before, during a game of spin the bottle, I had kissed one girl. She had braces, on her legs.

Pipsi sat at her carved Spanish dressing table. An open suitcase lay on the bed. Mike Kahan called me into his walk-in closet. The apartment was ridiculously huge and lavish, with a gilt-ceilinged library, stained-glass windows, a Monet. It had once belonged to J.P. Morgan. We were renting it with the money my grandparents had given us to buy a house.

“While we’re away, I want you to be careful, “ Mike Kahan said in the closet.

“Fine.”

“Seriously. Be careful.”

“You’re only going to be gone for the weekend. I can handle it.”

“Still. I want you to have this.”

He handed me a brown paper bag. I started to open it and he said, “Careful.”

Inside were four six-packs of Trojans. Twenty-four lubricated and ribbed rubbers.

“Keep it down,” he said through gritted teeth as I laughed. I tried to hold it in and felt stuff rise through my nose.

“What are you doing in there?” Pipsi called.

Still helplessly snickering and snorting, I went up to my room with the bag.

I was 19 with a freshly pierced earlobe. During Thanksgiving break, I went to visit a friend in Pittsburgh and dropped by the Piercing Pagoda, then returned home with a fair amount of trepidation. Pipsi had been explicit when I’d raised the subject before. I would look ridiculous with an earring, and she was against it. I had done so little to rebel during my adolescence, it seemed the least I could do.

When I walked into the house, Pipsi and Mike Kahan were waiting for me in the living room, wearing grave expressions. Before I could begin to defend my punctured earlobe, Mike Kahan said, “We have something important to tell you. Your mother is leaving us. She is in love with another man and has been having an affair with him behind our backs.”

It was clear from the way he made the announcement that he relished being the offended party. My mother at first said nothing, then came up to me and said, “I’ll have a bedroom for you in my place.” Then she paused and said, “Show me your ear.”

“Screw you,” I said and ran up to the room I already had.

I met Pipsi’s new boyfriend a few days later at their new apartment, four blocks from our house. After 10 minutes of small talk, Pipsi said, “George has a sports car, and he’s thinking he’d like to give it to you.”

“Well, said George, “Not give, more like sell at a very reasonable price…”

“That’s nice,” I said, “but I don’t drive,” and headed to my new room with the new bunk bed and new sheets and new rug and new framed poster of a flower.

“You could learn,” Pipsi called. “George could teach you. He’s a good driver.”

“We could work out a financing deal,” George said. Two days later, he and the sports car returned to his wife and kids.

Pipsi stayed in the apartment and Miranda and I moved back and forth between the two addresses. One day, as I came out of the subway, I saw Mike Kahan down the block. He was walking hand-in-hand with a dark-haired woman, and at first my heart jumped, thinking it was Pipsi. They’d reconciled. As they came closer, I saw my mistake.

“This is Sara,” Mike Kahan introduced the woman, one of his students, 20 years his junior. I saw more of Sara as she spent that night in our house. A few days later, I decided to confront Mike Kahan. Why were Miranda and I living with him and some other woman? We weren’t even related to him. We should be living with our mother.

“Look,” he said. “I’m the wronged party here. Unlike your mother, I value our home and our family, and I will keep it together.

“But you’re not,” I said, “You’re bringing in Sara.”

“My name’s Jessica,” said the woman.

“Yes, Danny. Things didn’t work out with Sara. This is Jessica. I introduced you already. Please don’t be so rude to the people I care about. Now give us some privacy.”

I went back to college, and when I returned several months later, Pipsi and Mike Kahan had reconciled and she was home. Mike Kahan made it clear that Pipsi was on some sort of probation. The arrangement lasted for another couple of years, after which Mike Kahan was the one to leave. Just before he did, he told Pipsi that during the time they had been together, a dozen years on three continents, he had slept with more than 300 women, including virtually all of her friends and neighbors. As Pipsi spooled out names, in disbelief, he nodded to each of them.

I was 21 and decided that if Keir knew more about me, he’d want to be closer to me. I wrote a book. Literally, I wrote 50 or more pages about everything I thought and knew and liked and felt. Because he once told me he wished he’d learned to be a bookbinder, I bound the pages into a book. I sent it off to him and heard nothing.

I was 21 and decided that if Keir knew more about me, he’d want to be closer to me. I wrote a book. Literally, I wrote 50 or more pages about everything I thought and knew and liked and felt. Because he once told me he wished he’d learned to be a bookbinder, I bound the pages into a book. I sent it off to him and heard nothing.

Years later and I asked him why he never mentioned the book I wrote for him.

“You didn’t write that book for me,” he said. “You wrote it for yourself.”

I was 25 and had never had a girlfriend for more than six consecutive weeks. A group of friends invited me to a trendy bar at 18 W. 18th St. The party was to celebrate the birthday of one Jellybean Benitez, the DJ of the moment, an intimate of Madonna. I didn’t know him or most of the scores of other guests. Although it was a Monday night, I outstayed my friends. Perhaps I was carried away by enthusiasm for Mr. Benitez’s happy occasion.

At several points, I noticed a girl across the room. Her hair was jet black, her dress wildly colored. Eventually I found myself next to her at the bar. She was trying to buy a White Russian but had no cash. The bartender refused to accept her corporate American Express for just one drink. I valiantly offered to pay.

“Taste it,” she said.

“But I have one of my own here.”

“I know. But taste mine,” she said.

And I did. “It tastes better than mine. Your lips must make it sweeter.

“You’re one of those guys, huh?” she said. I wasn’t really one of those guys.

“Not really. Want to taste mine?”

Minutes later, more than 20, less than 60, she asked me if I wanted to kiss her. I told her I wouldn’t compete with other men. I told her that when she was with me, she wouldn’t have to worry about money. I told her it was very nice down by the Hudson River and asked if she wanted to accompany me down there. Instead, we went to a nightclub. The goon at the door knew her and whipped the velvet rope aside. We danced, badly, and I walked her home at 4 a.m. She had had fun, she said, but wouldn’t see me again. It was June 16.

Her first name was Patti (actually, I thought it was Patty) but that was all I knew. I wrote a note, expressing how much fun I’d had the night before and hoping that if she regained her sense of humor she would call me. I went to her building. It was rush hour on one of the busiest intersections in Manhattan and people stared at me as I tore lengths of red tape and attached the note to her front door.

She waited two days to call.

Five years later, on June 16, I went back to 18 W. 18th St., drank a White Russian and married Patti.

At our wedding, during a pause in the processional, a divorced friend of Pipsi’s with two divorced sons of her own, was overheard to say, “It’ll never last.”

I was 26 and Patti I had been an item for six months when I fell in love again. We were at the Jersey City pound, a cinderblock building that smelled of disinfectant. I’d worked in much the same place when I was 11, back in Kfar Saba. That pound had been connected to the town slaughterhouse, and the vet to whom I apprenticed attended both places, providing bills of health to the condemned cows and then gassing unwanted pets. I hosed out kennels, butchered stillborn calves for dog meat, and emptied intestines for sausage casings. My only coworker was a piebald mule who stood hitched to a wooden cart under the abattoir. When his cart was filled with the shit that was dredged from the sausage casings, he would trudge to a pit, upend the cart till it emptied, then return to his post.

Patti and I browsed through the pound’s inventory. The only puppies were all siblings. They had been found in an empty lot, abandoned in a cardboard box. We chose the calmest of the litter and named him after Frank Sinatra. For the next 16 years, he joined us at meals, in bed, and on vacation. We dressed him up for Easter, Christmas, and Halloween and gave him endless nicknames (Houndy, Houndini, Houndenstein, Francise, the Beast, Pinknose…). He was our best friend and firstborn, our starter child.

Fast forward.