The essential American soul is hard, isolate, stoic, and a killer. It has never yet melted. —D.H. Lawrence

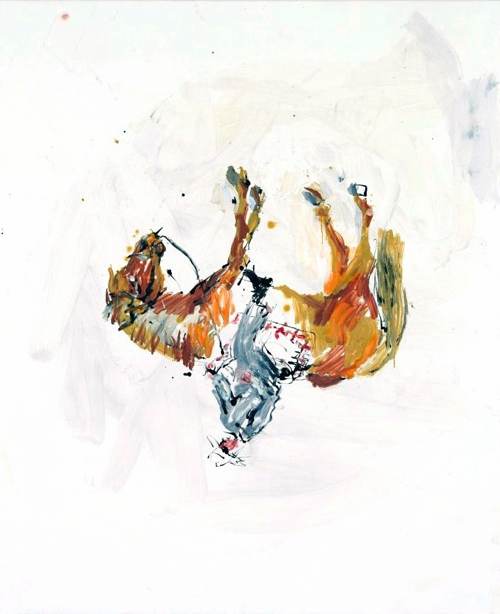

There is a truism in advertising that you should not sell drills but sell holes. After all, the ultimate purpose of the drill is not to whir fast or feel solid in your hand but to create a hole. The same is true of guns (and bullets). When all is said and done, you pull the trigger and there is a hole, maybe in a wall or a target, or maybe in a human skull.

Modern guns are good at making holes. And if guns were used only for hunting and target shooting, the holes might be useful or even fun. But guns aren’t just used for hunting and target shooting; they are used when life is at its most fraught, in fights, in self-defense, in crimes, and to commit suicide. They make holes in people and holes in homes, and for two years in the late 1990s, I lived surrounded by thousands upon thousands of these hellish holes in a little town in eastern Croatia called Pakrac.

Pakrac featured the classic elements of a late 20th-century Balkan conflagration: neighbor killing neighbor, shelling of civilians by the army, and massacres by outside death squads. The town changed hands five times in street-to-street fighting, and for more than three years, a ceasefire line ran through its center, with snipers taking aim at any driver brave or reckless enough to run the road that served as part of the line. Croats burned Serb homes on the Croatian side, and Serbs bombed Croat homes on theirs until, finally, the Croatian Army swept out the Serbian forces in 1995.

I came to Pakrac three months after the last fighting, and while the guns were already gone, or at least hidden, every surface of every building was a random pattern of blasted plaster. I soon learned to tell which houses had burned, which had been bombed and which had been blown up. But all of them had been shot.

I also lived in the psychic echoes of those tiny voids, talking for hour upon hour with old people in broken Serbo-Croatian about their families and friends, all either dead or fled. I heard machine gun fire many nights, and a local war hero once shot his brother over a game of cards. But I faced a gun only once, when a drunken ex-soldier set it down on a café table, pointed right at me, as he rambled about the deceitfulness of the Serbs.

Pakrac was a world with mines exploding in the forest and 23 bars for 5,000 people and the constant exposure to the physical destruction of the town, and to the psychic trauma of the residents, engendered a slow, sneaky stress that found my weakest points.

I lived in the psychic echoes of tiny voids, talking for hour upon hour with old people in broken Serbo-Croatian about their families and friends, all either dead or fled.

I tried desperately not to shut out the pain but to recklessly embrace it, terrified of the detachment I saw in the townspeople and other volunteers. I found empathy and gentleness through that pain but, by the time I came home, I was both alienated and fragile.

Fast forward to Sept. 11, 2001. I lived in the exurbs northwest of New York City, and I had a different reaction to the terrorist attacks than most people I knew. I was not shocked, and I was not angry. Instead, I was weary, wandering in the echoes of explosions and witness only to the holes, not to the airplanes that acted like jet-propelled bullets. I worked at a suburban newspaper then, and after months of covering funerals, sitting in the living rooms of dead firefighters and taking notes across tables from parents recounting cell phone conversations with a panicked and doomed child, I was hollowed out once again.

As 9/11 turned into war in Afghanistan and then in Iraq, it became fixed in my heart that the bad guys were winning, the U.S. was a kill zone, and right-thinking people were under siege by fanatics spouting off about their rights under the Second Amendment.

But it is not good to live too long with unexamined certainties. I live in Sweden now, where guns and violence in general are non-issues. The war in the Balkans appears as a fratricidal outburst that should have, would have, could have been avoided. But in the U.S., the killing never stops, and the Newtown massacre—and the subsequent shouting about gun control—roused me from my Scandinavian complacency.

What I went looking for was an answer to a deeper question about the metaphoric holes left in a person, a family or a community by murderous acts, whether by guns, knives, or bare hands. If nothing else, talking about guns can serve as a beacon, starting me on the road toward answering the question: Why do Americans kill so much?

I turned first to the everyday gun deaths catalogued post-Newtown at Slate, via @GunDeaths on Twitter. The numbers add up so fast, at the pace of a Columbine massacre almost every day, with each murder a head-twisting disaster, either a torturous tragedy like a murder suicide in a lonely house at the end of a cul-de-sac or something cheap and casual like a shooting after a drunken fight outside a nightclub. I got lost in the stories, in the heat of human passion or the coldness of a premeditated murder. Each violent death creates ripples of rage and grief that pulse through family and friends and down generations. Think then of all those ripples flowing together to create waves that wash over the American soil. Each time I visited the Slate gun deaths page, I felt myself disengaging, suddenly back in wasted Pakrac or revisiting the psychic scars of firefighter families in late 2001.

The data on gun ownership, gun crime, and gun deaths are a morass of flawed polls and comparative rates that, as with all statistics, usually tell you what someone else wants you to hear.

Let’s just look at March 10: an elderly murder-suicide in Marietta, a shooting outside a bar in Camden, a fight-related shooting in Miami, a police shooting of a man threatening a woman in Dallas, a police shooting of a man holding a shotgun in Memphis, a shooting outside a nightclub in Philadelphia, a man shot down by a woman in a post office in Jacksonville, a man driving an Aston Martin shot to death in Oakland, a shooting in Dallas, a shooting in Hampton, a nightclub shooting in Calcasieu Parish, and a 16-year-old boy in Brooklyn who pulled a gun on police and got shot.

So I turned to statistics, looking for hard truths behind the human drama and political rhetoric. But the data on gun ownership, gun crime, and gun deaths are a morass of flawed polls and comparative rates that, as with all statistics, usually tell you what someone else wants you to hear. Plus, huge chunks of the information are based on telephone surveys, and your guess is as good as mine whether to trust those.

But there are a few more relevant and reliable numbers.

- Americans have the highest rate of civilian gun ownership in the world, with a rate of about 88.8 guns per 100 people in 2007, more than a third higher than the next highest country, Yemen.

- Since 2007, the rate has surely risen even higher. There were approximately 310 million guns in the U.S. in 2009, 40 million more than in 2007, according to data released in 2011 from the U.S. Department of the Treasury, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms. There are only approximately 315 million people in the U.S. today, so the rate is likely closer to one gun for each American, even as gun and ammunition sales and FBI background checks continue to skyrocket.

- The number of people killed by guns in the U.S. is dropping like a stone, with the gun murder rate falling from 6.6 per 100,000 people in 1993 to 3.2 in 2011. This reflects a broader collapse in crime over the same period but the numbers remain dramatic, with juvenile gun deaths dropping 58 percent and accidental deaths plummeting 64 percent between 1993 and 2009.

- Still, even with these declines, the U.S. remains an outlier in its gun-related homicide rate, with its rate dwarfing almost every other developed country. For example, the U.S. rate is eight times that of Croatia’s and 32 times greater than the rate in England and Wales.

So what’s it all mean?

When I started my research, I must admit, I assumed the academic literature would turn up unassailable arguments along the lines of this headline from Harvard: “Where there are more guns there is more homicide.”

But the literature on guns is just as messy as the statistics—often completely contradictory, with some studies showing convincing correlation between guns and homicide, while others equally convincingly show none. In the end, most of it shares an unfortunately quality: too much of the language implies causation (or lack thereof) between guns and death but only really shows varying levels of correlation. This is a problem in much social science research, but seems particularly vivid here. A Centers for Disease Control task force in 2003 summed up the situation nicely: “The application of imperfect methods to imperfect data has commonly resulted in inconsistent and otherwise insufficient evidence with which to determine the effectiveness of firearms laws in modifying violent outcomes.”

Talk about a moving target.

But the ambiguity can be useful, if you’re willing to explore the dark gap between correlation and causation. So if we can give up on guns as the root of the problem, just for a while, there are a host of possible other causes for the special American brand of rich country violence. Let’s start with what we are not going to discuss. The list runs very roughly from least relevant to most relevant:

- Hurricanes. Tornadoes. Riots. Terrorists. Gangs. Lone criminals

- Race

- Mental illness

- Drug use

- Religiosity or lack thereof

- Violent media and video games

- Poverty

- Gun control laws or lack thereof

- Crises of masculinity

- Culture of honor

- Public faith or lack thereof in government

- Inequality

Of all these, income inequality rings the most true—and there is high correlation between inequality and homicide in studies—but beneath even that there is another issue that transcends all the standard bugaboos of race, class, and poverty, one possibly rooted deep in the primate building blocks of humanity.

It’s called social capital, and while it’s a relatively new term, it is an old concept, with American roots reaching as far back as Alexis de Tocqueville and his classic analysis of the United States in the 1830s, in which he identified both American individualism and an American propensity to gather into groups “very general and very particular, immense and very small.”

“No sooner do you set foot upon the American soil, than you are stunned by a kind of tumult; a confused clamour is heard on every side; and a thousand simultaneous voices demand the immediate satisfaction of their social wants,” he wrote. “Everything is in motion around you; here, the people of one quarter of a town are met to decide upon the building of a church; there, the election of a representative is going on; a little further, the delegates of a district are posting to the town in order to consult upon some local improvements; or in another place the labourers of a village quit their ploughs to deliberate upon the project of a road or a public school.”

This engagement was central to de Tocqueville’s understanding of American democracy. He saw voluntary groups spreading like wildfire (among primarily white males, of course) and filling a gap between family on the local end and the state on the more distant end. And it was in this middle ground that de Tocqueville perceived a budding sense of a new and better common good.

There is another issue that transcends all the standard bugaboos of race, class, and poverty, one possibly rooted deep in the primate building blocks of humanity. It’s called social capita.

Both in academia and the wider culture, social capital burst into the national consciousness in the mid-1990s, driven by political scientist Robert Putnam, who defined it as “the collective value of all ‘social networks’ (who people know) and the inclinations that arise from these networks to do things for each other (‘norms of reciprocity’).”

It includes everything from voting to dinner parties to Little League, from religious groups to farmer’s markets and the local zoning board. It includes Facebook, yoga classes, picnics of all kinds, hanging out on the stoop, and watching over the neighbor’s kids. Putnam raised an alarm about declining social capital, pointing to precipitous drops in the very voluntary associations—the Rotary Club, the Boy Scouts, the Jaycees—that de Tocqueville had gushed over and writing that “we are becoming mere observers of our collective destiny.” He attributed the decline to sprawl, television, and demographic shifts, but his underlying focus was on the struggles of dual-income middle-class families whose overworked members were not able to participate in wider society as they once did.

There are two kinds of social capital—bonding and bridging—and each impact a society differently. Bonding capital is what you get within a given group. These tend to be closer and more reliable bonds that form the foundation of our social capital. Yet bonding social capital is not always positive: Tight-knit groups can turn insular, reaching their logical conclusion in gangs and militias but with negative effects found in everything from families to groups of friends to certain kinds of religious communities.

In contrast, bridging social capital reaches across a societal divide such as race, region or religion and is by nature weak. But it also promotes empathy and tolerance and enlarges our radius of trust, allowing us to see other people as people, not as a faceless other.

This sense of bridging a divide is especially important in the U.S. because, contrary to popular opinion, we regularly put the needs of the group ahead of the needs of the individual in a way Europeans don’t. In surveys, Western Europeans are more likely than Americans to say citizens should follow their conscience and break an unjust law or that citizens should defy their homeland if they believe their country is acting immorally.

On the other hand, Americans are more likely to believe they control their own fate and to believe in a more laissez-faire relationship with the state. It’s a more complex mix than our myths allow for, and the end result is that it can be hard to fathom just how different Americans are from the rest of the world.

This sense of bridging a divide is especially important in the U.S. because, contrary to popular opinion, we regularly put the needs of the group ahead of the needs of the individual in a way Europeans don’t.

Americans believe in contracts—or covenants, as sociologist Claude Fischer puts it: “Our culture insists that if you marry, if you take a job, if you join a club, and so on, you are signing an explicit or implicit contract to cooperate and conform. If the group no longer works for you, the door is open.”

It’s an all or nothing approach that seems riddled with anxiety, with banishment or voluntary exile lurking behind every disagreement. It makes us hold tight to what we have because the threat of isolation is a very real one.

By contrast, here in Sweden, people take membership in the larger society for granted. You don’t have to join anything, and, for most Swedes, the whole purpose of this big national group is to protect the rights of the individual members. This is what Americans often miss about the welfare state: It is about ensuring personal dignity, no matter the circumstance of the citizen. And, with that dignity intact, people can question the group because they know they’re never leaving it, and it will never reject them (even if they are occasionally put in their place). This is an idealized view of Sweden, but it is true in essence, if not always in practice. It has its roots deep in Swedish history, which is more diverse than most people think, filled with fierce regional identities, German-dominated cities, steady Walloon immigration, rule over Finland and Norway, and the Swedification of Danish Skåne—now southern Sweden—starting in 1658 and continuing, some might say, until today. But what is more important than this rarely recognized diversity is a tradition of a modest nobility, relatively independent peasants, and a deep-rooted Lutheranism that puts the individual, not the church, front and center in the relationship with God. This created a culture of relatively equal partners who bargained on relatively fair terms, which led to a broad sense of trust in strangers (at least ones from Scandinavia) and contributed to the strong belief in the rights of the individual. To this day, these political traditions reinforce openness and transparency, creating a virtuous circle of a strong economy, good social capital, and more trust.

In Croatia, on the other hand, I lived in the gap between deeply bonded Croat and Serb communities, and, in fact, my mission was to rebuild bridging social capital between them. Before the war, the town had been split relatively evenly between Croat, Serb, and “Yugoslav,” and there were more inter-ethnic marriages than not. The area had been depopulated during Turkish invasions and then repopulated by the Hapsburg Empire to serve as a buffer against nearby Ottoman Bosnia, so there was no tradition of ethnic warfare tied to historical claims. Yet the bridges between Croat and Serb were probably never as strong as some people claimed afterwards—imposed to some degree from an authoritarian state—and they had crumbled under the pressure of outside nationalism, the collapse of the Yugoslav state, and the suppressed trauma of World War II, with the notorious Croatian-run Jasenovac concentration camp only a few miles away.

In the late 1990s, lost in the postwar haze, I saw only the bullet holes and heard the bitter, likely apocryphal, stories of Serbs abandoning Pakrac the night before the Serbian-dominated Yugoslav Army started shelling town from the hills above. I could only guess at what had gone so wrong that this little town would turn on itself (with much outside help) so viciously.

The Croats and remaining Serbs did, however, co-exist far more respectfully than I expected, with Serb kids going relatively peacefully to the local school and with little ethnic violence of any sort. This was clearest in contrast with the local Croat attitude towards ethnic Croat refugees from Bosnia and Kosovo. The three groups shared no real culture, save for a vague ethnic identity, and after one brawl between local and Bosnian Croats in a nearby town, a Croat I knew said to me, “It just makes me wish all the Serbs would come back. They were so much more like us.”

In the U.S., public health researcher Ichiro Kawachi published a paper in 1999 based on national data that showed that social capital had a higher correlation with homicide than any other factor. According to this theory, communities with low social cohesion get caught in a vicious cycle of violence destroying social capital, which leads to more violence and so on. There are fewer checks on bad behavior, families get broken, jobs disappear, schools go bad, and kids get lost.

What if a cultural embrace of violence—and we’re not talking about the right-wing talking point on our “culture of violence” here—is actually at the root of the killing instead?

So what comes first: the murders or the low social capital? It seems intuitive to say that unstable communities would lead to more violence. But what if a cultural embrace of violence—and we’re not talking about the right-wing talking point on our “culture of violence” here—is actually at the root of the killing instead?

Perhaps, like a true original sin, groups in power in the U.S. have systematically destroyed social capital in vulnerable communities and between groups of all kinds in order to gain wealth and power and deny it to others. And perhaps they have done this in more ruthless fashion than in other comparable cultures. This could explain why the murder rate in New York has been more than five times higher than London’s for 200 years, though the American propensity for violence reaches even farther back than that, going all the way back to frantic religious refugees with visions of the Apocalypse both at their back and before their eyes.

Imagine that you live in New England in the mid-17th century. You fled mother England to escape not just religious oppression but also what you believe is the coming Apocalypse, the final destruction of all that is sinful in the decadent Old World.

You are a member of John Winthrop’s flock in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, submitting your individuality to the larger community onboard the flagship Arbella in the vast Atlantic Ocean in May of 1630. Or you arrived a decade before on the Mayflower and signed the Mayflower Compact, and you hold your faith so deeply that you would rather starve or die of disease than submit to the tyranny of the English king. You do this because you know the dark truth that we are all doomed, that our original sin cannot be cleansed. You once possessed such fervent faith that you could build a shining city upon the hill, the new Jerusalem, but, already, here in the Massachusetts Bay or Plymouth colonies, it’s clear that there will be neither walls of jasper nor streets of gold, and that not only is your nascent community doomed by heresy from within, but that you must wade through rivers of blood in battle with the proxies of Satan, whether the original inhabitants or the French or the Dutch.

War came early to your nascent colony, barely more than a decade after the first boat landed. The Pequot Wars of the mid-1630s were as much between native tribes as between the English and Pequot, with the balance of power not always on the English side. It was a brutal war over territory and the fur trade, but it was also a war that you and your brethren injected with all your tortured fervor, and it was a war that helped define you in this new American context.

In the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries, Americans laid more of their terrible bricks—the genocide on the Great Plains, the myth and occasional reality of a lawless frontier, the slaughter of the bison, brutal segregation, Prohibition and the rise of organized crime.

By the 1670s, the colonists far outnumbered the Pequot and other tribes, who were decimated by disease and under severe economic and territorial pressure from the British. The social order was in flux, with Puritans going native out in the woods and Native Americans converting to Christianity in the towns. In 1675, war broke out again, as the British provoked the Wampanoag tribe and its allies, led by the native chief the English called King Philip, into opening the seal on the most deadly fight in American history in terms of percentage of population killed.

In King Philip’s War, up to 40 percent of the native population died or fled the region, one out of every 10 colonists perished, and one-half of the towns in New England were ravaged, as a small band of native soldiers almost drove the British back into the sea. It is powerful to picture New England as a wasteland, and both sides pushed far beyond their cultural norms, torturing prisoners, mutilating bodies, and killing children. In a speech, historian Jill Lepore evokes “a landscape of ashes, of farms laid waste, corpses without heads, a place where three-legged cattle wander aimlessly, dragging their guts after them.”

The English won in 1676—sticking King Philip’s head on a stake, where it stayed for decades, a place of pilgrimage. His followers who survived were, as you would guess, doomed to servitude, disease, and the loss of their ancestral lands, even those who had become Christian and supported the colonists. Yet, at the same time, murder rates among the people who remained in New England, now unified by race and nationality, plummeted.

A foundation of brutality had been laid, and, in the ensuing decades, Americans constructed their house of pain brick by brick, starting with one for the radical anti-militaristic (but pro-militia) politics leading up to American Revolution, another for the culture of honor in the South and West, and another for the Civil War and the failure of Reconstruction.

Then in the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries, Americans laid more of their terrible bricks—the genocide on the Great Plains, the myth and occasional reality of a lawless frontier, the slaughter of the bison, brutal segregation, Prohibition and the rise of organized crime, the terror of the Cold War and the Second Red Scare, the Vietnam War and the domestic chaos around it, white flight, the crack cocaine epidemic, the war on drugs, long years of fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan, the spurt of mass shootings over the past 15 years, and the manic spike in gun sales that we’re seeing right now.

That brings us to today, when, simultaneously, we are in a social revolution, one of feminism, of globalization and of a future as a majority-minority country. The digital economy and the creative class are booming in places like Silicon Valley and Boston, while gay marriage goes mainstream, a black president gets reelected, interfaith cooperation rises, and young adults in large numbers flee the suburbs, forgo buying cars, and occupy public spaces nationwide in the name of the 99 percent. There might still be a libertarian streak in all this but it is one of rights—of the right to marry, to smoke, to define oneself—that seems more communal, more of a peaceable city and how we negotiate it.

Then there is the connected world of Facebook and Foursquare, Twitter and Vine, and while there is fierce debate over the strength and nature of social media ties (as well as the social effect of the internet as a whole), people clearly build social capital of some sort on these platforms, both bridging and bonding. You can see this in the data from Facebook after millions of people replaced their profile pictures with a symbol to support gay marriage. The campaign was started by the Human Rights Campaign, but the symbol spread virally, and the highest percentages of changes were in uber-connected places like college towns and the Bay Area, with a moderate correlation for population density nationwide.

From the ascendant liberal viewpoint, it is easy—but dangerous—to dismiss out of hand these deeply and honestly held beliefs from people who could match the Puritans for their zeal.

Yet progress lags in what Rebecca Solnit calls the “low-pressure zones” of the U.S, the areas left behind economically and socially, and it is in many of these places that people are feeling besieged, marginalized in some larger cultural sense even as they control much of the political machinery. The more extreme of them are slipping into apocalyptic time, with visions of the four horsemen of the Apocalypse charging across the plain, like this from Matt Barber, vice president of Liberty Counsel Action, a Christian-right advocacy group: “I fear this nation, already on the precipice of widespread civil unrest and economic disaster … might finally spiral into utter chaos, into a second civil war.”

From the ascendant liberal viewpoint, it is easy—but dangerous—to dismiss out of hand these deeply and honestly held beliefs from people who could match the Puritans for their zeal and who, like the colonists in 1675, are deeply unsure how to survive in a world in which the traditional “other” is disappearing and new divides of class, geography, and single-issue orthodoxies are opening.

And this is where I come back to guns, for what kind of gaping hole in our society requires 310 million guns to fill it?

Buying a gun in our times, especially for self-defense, seems to me an aggressive or defensive act—a statement by the purchaser about how he feels about his community, his neighbors and his country. It means he doesn’t feel safe in his bed at night, that he doesn’t trust the police to stop the criminals, and he doesn’t trust his fellow citizens not to attack. You can mask it with talk of freedom or the Constitution but underneath it all is fear. Firearms have become a manifestation of a massive distrust of both government and the wider society, a physical manifestation of a deepening societal and political divide.

I don’t mean to ignore the millions of hunters and target shooters, for whom guns carry none of this loaded symbolism. Partisans on either side unfairly dismiss these people, but, rightly or wrongly, guns have become a symbol for currents deeper in our national soul than discussions on hunting and skeet shooting, and we need to talk about guns, if just to work out where we want this country to go.

So, like, what do we do?

I’d like to address that question with an excerpt from what I consider the best presidential speech of my lifetime:

“Our public interest depends on private character, on civic duty and family bonds and basic fairness, on uncounted, unhonored acts of decency which give direction to our freedom …

“I ask you to seek a common good beyond your comfort; to defend needed reforms against easy attacks; to serve your nation, beginning with your neighbor. I ask you to be citizens: citizens, not spectators; citizens, not subjects; responsible citizens, building communities of service and a nation of character.”

I listened to this speech driving my Plymouth Neon alone through heavy traffic in New Jersey, heading back to my basement apartment in Mechanicstown, N.Y., on the edges of Middletown, which is on the edges of the New York City suburbs, where I was spending my nights at zoning board meetings and my days wandering around empty exurbs, and, for a moment, I had this sense that, hey, there is hope. Everything might just be all right.

The year was 2001, and the president was George W. Bush giving his first inauguration speech, and everything definitely did not turn out all right.

But it remains a hell of a speech, one that fleshed out “compassionate conservatism” in a way that soothed my suspicious soul and took it beyond a crass code for starving the government and punishing the poor. After his vapid campaign and the disputed election, Bush talked about community more than the self-made man, and he urged us to work together—and with the government—to build a comity and to share a vision of a better society. He called us to sacrifice, even, and in retrospect, the words could easily have come from Bill Clinton or Barack Obama, whose first inaugural address was not nearly as soaring, either live or on the page.

How do we help people feel safe enough that they don’t need four guns and a shed full of ammo? Get involved.

It seems clear that Bush, or someone on Bush’s team, got that whole vision thing when it came to the state of American society at the turn of the century. Of course, after the speech came nine ineffectual months and then 9/11 happened and then fear became smart, and trust and social capital were for suckers. With the Great Recession and Obama’s election and the deepening of the partisan divide, this dynamic has changed in ways both hopeful and sickening.

So how, after all this, do we start trusting that our neighbors—either immediate or in a broader sense—can be trusted? How do we build trust that the government—just talking the basics of public safety and public health here, though I’d love to bend your ear about parental leave and the value of a strong safety net—can bring peace and prosperity?

How do we help people feel safe enough that they don’t need four guns and a shed full of ammo?

Get involved. For the best social capital is built naturally, with communities coming together—both inside and outside government—and then linking in ever-larger circles. Sociologists Blaine Robbins and David Pettinicchio examined social capital and homicide globally and found that, above all else, social activism exhibits a “significant negative association with homicide rates, net of other influences.”

“This is because politically oriented individuals are also more likely to serve the needs of their community and assist in collective endeavors aimed at reducing crime,” they wrote. “All of which follows the classic Tocquevillian premise: a willingness to take part in political affairs generates a willingness to contribute to the common good, including the production and maintenance of a safe and secure society.”

Yes, they are talking about community organizing. They are also talking about what I did in Pakrac, where we called it social reconstruction and where big players like the European Union and the United Nations called it building civil society. But it’s also called serving on the school board or signing a petition to save a wetland or showing up at a planning board meeting to support a new business. It is about interfaith movements to help the homeless, attending political meetings (from socialists to tea party groups), and bending the ear of your state senator at the volunteer fire department’s pancake breakfast.

Of course, the work of Robbins and Pettinicchio shows only correlation, not absolute proof. But I accept now that nothing is going to prove causation when it comes to homicide (or guns), and, in my judgment, the literature on social capital provides enough proof to make a moral judgment, even if it is naturally imperfect.

This is not a liberal or conservative thing. It is a citizen thing, and this act of making others’ conditions our own is not foreign to the American experience. We don’t all have to get along, and we don’t have to sit in a big circle and sing Kumbaya. But we do have to agree to disagree through reasonable and rational channels, rather than with the apocalyptic brutality—both physical and emotional—that marks so much of American history.

Through millions of small acts, we must come to a larger agreement on what we want our nation to be, something never wholly accomplished during the Revolution and something never really tried since. And while we should never betray our respective ideals, if we are given a fair hearing we must accept the decision of the group, even as we can work to change or overturn it. This will not be an easy road, as introducing democratic ideals into societies divided by caste and class is “profoundly disruptive,” according to historian Randolph Roth. It will also not prevent individual massacres—for which more immediate prescriptions such as gun control laws or better mental health care may provide moderate help. But even with gun control and public health campaigns, our homicide rates will not fall significantly until we succeed in our larger mission.

As an outsider in Pakrac, first in a grassroots peace project and later with a U.S. government-funded NGO, my work was often both pointless and self-serving. But I was never able to reject it completely, and when my presence among the bullet holes and the collective trauma seemed particularly random, I told myself that I could only hope that in 50 years my work might pay off in ways big or small. Maybe one of our wispy bridges between Croat and Serb would endure—empathy for a struggling old woman or an introduction between two former soldiers—or maybe the children and grandchildren of the members of a women’s group might make a multi-ethnic business deal or approve of a Croat-Serb wedding or, this is the big hope, somehow help stop the next war before it starts.

In the U.S., we need to make a conscious decision to be one country, and we must hope that the better angels of all our faiths and creeds will win the day. We must fulfill the promise of de Tocqueville and find liberty not in isolated selves or clans but in the exercising of our local democratic rights, in the dignity of the individual within the caring community. Only by bridging our divides will we preserve freedom and possibly atone for our national sins.

And here is why I still worry about guns, even if they are not the root of anything, and this is almost purely grounded in my time in Pakrac. Guns are not an idea or a prejudice or an emotion. They will not pass like opposition to gay marriage or dangerously moronic views on rape. They are objects, and they will endure. They get stolen, sold, found, and washed into the loneliest, least connected places, where they do the most damage. And at some point, violence has the potential to build beyond murder to something even worse—riots, wars, pogroms—and then I say that a concentration of guns does matter, too much tinder to be ignited by too small a spark.

The United States is a young country with much blood on its hands. But it is also a young country filled with independent yet community-minded citizens who can evolve and build bridges and stop the killing. And if that happens, 300 million guns might rust away, and no one will ever pull their triggers, and there will be no more blasted holes.