At 6:00 this morning, I set out for Woodstock Square by foot. The clerk at the Best Western called a cab for me, but there was no answer. It’s four degrees outside, and windy, so when I see a building labeled police department, I walk in to ask for a ride. After some questioning, my request is granted, and I find myself in a police cruiser with Officer David. There were no cabs, I tell him apologetically. “Oh, there’s one guy,” he says. “But, you know, he’s been busy with the storm and the Super Bowl and all.” He grants my request to sit in the front seat and drops me at the square, just in front of Starbucks.

In Starbucks, I run into Rick Bellairs, the organizer of the Groundhog Days festival. I ask him if he expects a large turnout. “No,” he says, laughing. He suspects the weather will keep people away. Bellairs invites me next door, to the Stage Left Cafe, where the polka band and committee members are warming up. It’s here that I get a different sense of the event. Before it was Groundhog Days, the multi-day celebration, it was an annual breakfast, just an opportunity for local participants to gather and tell stories about their days working on the film. The mood at Stage Left is convivial, neither totally earnest nor ironic. Here in the Midwest, inclement weather means one might go weeks without seeing friends—this time of year, I can go weeks without seeing my next-door neighbor—and Groundhog Days is, to locals, something to do in February.

When light dawns, we head out to the square. About a hundred people are gathered, bundled tightly, to hear the weather report. The band plays “Woodstock Willie’s Polka.” It includes the line, “everybody had the mania / to sing in Woodstock, not Pennsylvania,” which gets a big cheer. Richard Henzel, who plays the DJ in the movie and usually comes down to reprise his role for the festivities, has canceled due to the weather, so Bellairs and fellow committee member Craig Krandel step in to do the morning DJ bit as people in the audience shout along. A representative from Home State Bank, Groundhog Days’ biggest sponsor, knocks on Woodstock Willie’s log, and, after a brief huddle, six more weeks of winter is declared.

After the prognostication, we adjourn to the Moose Lodge for the annual Groundhog Breakfast. The polka band plays. Groundhog Day is running, muted, on the televisions in the corners of the rooms. I am finally eating a real meal. Bob Hudgins, the location manager, who came in from Austin, gets up to speak. He’s been coming to the fest for more than a decade, but looks humbled and happy, standing before a packed room. This town’s got a bit magic, he says. “The fact that we are here, and it’s all because of a silly movie. Harold Ramis made a good one.”

On Friday night, at the annual Groundhog Dinner and Dance at the Moose Lodge in Woodstock, Ill., Theresa from Sun Prairie, Wis., approaches my table after noticing my recorder and notebook. Visiting the town where her favorite movie, Groundhog Day, was filmed, she tells me, was on her bucket list, and she was surprised to learn she wouldn’t need to travel all the way to Punxsutawney to cross it off. She and her husband drove down earlier in the afternoon, and are staying through the weekend.

She becomes flustered when I pick up my recorder. “Am I going to be on TV?” she asks. She declines to state her last name with a wave of her hands, declaring she is not important enough to be interviewed. But she does have some advice for me.

“Here’s what you can say in your story: Hey, campers! You don’t need to go all the way to Punxsutawney. You can come right here to Woodstock, where Bill Murray made the film and it’s so special.”

Theresa’s response is far from unusual here at Groundhog Days, a five-day celebration of the filming of the 1993 movie in Woodstock, 50 miles northwest of Chicago. The attendees can be divided into two camps, each as enthusiastic as the other: the tourists, who are rapturous about the film, and the locals, who are rapturous about their town.

Chuck Friedel, who has lived in Woodstock his entire life, is also at the Moose. We met while I was scoping a table of raffle prizes—jerseys for all major Chicago sports teams, a large package of Lotto scratchers, gift cards to various local shops—and the woman selling raffle tickets introduces us. “He’s from the movie!” she says. Friedel, whose graying ponytail is hidden behind a newsboy cap, looks a little embarrassed and a little proud. He explains how, 23 years earlier, he got involved with the movie.

“I’m a carpenter, and it was a slow time,” he says, so he joined the line of hopefuls at the local high school, where extras were being cast. “The first time, I was going to be a police officer, but that didn’t work out.” However, once filming for the dance scene toward the end of the film was underway, he got a second chance. “We were downstairs in the basement of the Moose here, and a good friend of mine got picked [to dance] and she said, ‘I want him for my partner.’” (The next day, at a screening of the film, I will recognize him, just behind Murray and Andie MacDowell.)

I ask Friedel if he ever thought, back in the days of filming, that the movie would have such a big impact on the town, and he tells me he had no idea Woodstock would be such a sustaining source of interest. “It seems like it gets bigger and bigger each year,” he says, noting that he’d met people who’d traveled from across the country to visit the festival this year. But its enduring success, he says, is because of the friendliness of Woodstock, which he describes as “a very nice, quaint town.”

On Saturday, the third day of the festival, the weather is sunny but cold, and as I make the drive from Chicago, I watch the suburbs give way to increasingly rural landscapes, interrupted with clumps of new housing developments. Mostly, the vistas are still straw-colored prairie grass and farmland dotted with snow. The houses leading up to the square in Woodstock are pretty and Victorian, reflecting its long history. It is picturesque in a way that feels Midwestern—not like the Midwest I’ve known as a Chicago dweller these past five years, but the Midwest I imagined, as I was growing up in Southern California. It’s the Midwest of the movies.

I was born and raised in Downey, a working-class city about 10 miles outside of LA proper, and I grew up in a world that was not at all Hollywood. Still, to live in Southern California is to have a substitute teacher who is in a Cracklin’ Oat Bran commercial; or to know a kid at church whose mom supplements the family income by picking up work as an extra; and, of course, to see one’s neighborhood on screens big and small. The filming in my hometown was interesting enough that everyone could rattle off the films that had been shot there, but common enough that it wasn’t a source of enduring excitement. The cult film Suburbia, which follows homeless punk youth squatting in a tract of abandoned houses, was filmed in my neighborhood. When those homes were finally razed, the movie Speed was shot on the freeway that replaced them. Later, industry scouts would repurpose our long-closed Rockwell plant and use the empty lot and aerospace hangars to film some of the biggest blockbusters of the early 2000s. (Downey Studios, despite of the many films made there, only lasted a dozen years. The buildings were demolished last year to make way for a shopping center.)

Christian, Jewish, and Buddhist groups have all embraced Groundhog Day, saying the movie demonstrates important tenets of their religions. But I think it’s a perfect film for atheists.

I pull into the parking lot behind the opera house, which served in the movie as the Pennsylvania Hotel, and I’m struck by how familiar the square looks. More so than at the Moose, I feel transported to Harold Ramis’s Punxsutawney-cum-Woodstock. To me, Groundhog Days seems a little absurd—a town most famous for impersonating another, more famous town, and reliving the same moments, engaging in the same movie trivia, year after year, that’s not at all unlike the Groundhog Day’s premise. I also kind of get it—the film is such a picture of the town, and the town bears such a resemblance to the film, that it’s exciting for anyone who loves this town to see. Rarely is so much of a movie filmed so much in one location.

This morning the Woodstock Theater (renamed the Alpine Theater in the film), will play free screenings of Groundhog Day, as they do every year. The theater is packed, and smells of popcorn and cough drops. We are one of four auditoriums showing the movie, and before the screening begins, festival organizer Rick Bellairs visits each one to say a few words about Harold Ramis. One of the newly refurbished auditoriums is being dedicated to the director, who died last February. Ramis grew up in Chicago and, after a few years in LA, returned to the area in 1996. He even visited Woodstock for Groundhog Days once, on the five-year anniversary of the film’s release, and locals remember him fondly. They clap and cheer when he first appears on screen, as the neurologist who examines Bill Murray. They also cheer when the news van pulls into the town square for the first time. Beyond that, the viewers are quiet, except for occasional laughter. I half-expected people would call out favorite lines, or that the screening would otherwise be interactive, here in this room of superfans.

After the screening, I meet Alden Riak in the lobby. He was born two years after the film was released, and grew up in Woodstock. “Ever since I was little,” he says, “we’d come to the Groundhog Days festival. The entire week of Groundhog Day was basically one long holiday.” I recall the families that had gathered to watch the movie in our auditorium, the mothers quietly explaining morsels of trivia to children during the trailers. I ask Riak, who estimates he’s seen the movie more than 20 times, if he’s sick of it yet. “Not at all!” he tells me, beaming. He’s going away to college next year, but plans, always, to return to Woodstock. “It’s a beautiful town,” he says.

Christian, Jewish, and Buddhist groups have all embraced Groundhog Day, saying the movie demonstrates important tenets of their religions. But I think it’s a perfect film for atheists. For Phil, there is no tomorrow. Sure, at the end of the movie, the day turns. But Phil has no faith that the day will change. He cycles through his baser instincts, but the conquests and manipulations, day after day, lose their luster, and he begins to change. It’s an existential problem—who is not living the same day, over and over?—with an existential solution. Phil needs to create meaning in order to live happily, and by the end, even lacking all evidence of a future, let alone a higher power, he does. He turns his attention to self-improvement, using eternity as an extended opportunity to learn, and the town is his university, its “hicks”—as he calls them in the movie—become his teachers. Perhaps that’s why Woodstock residents also embrace the movie. If Phil is an anti-hero for much of the film, the townspeople are the unfailing heroes.

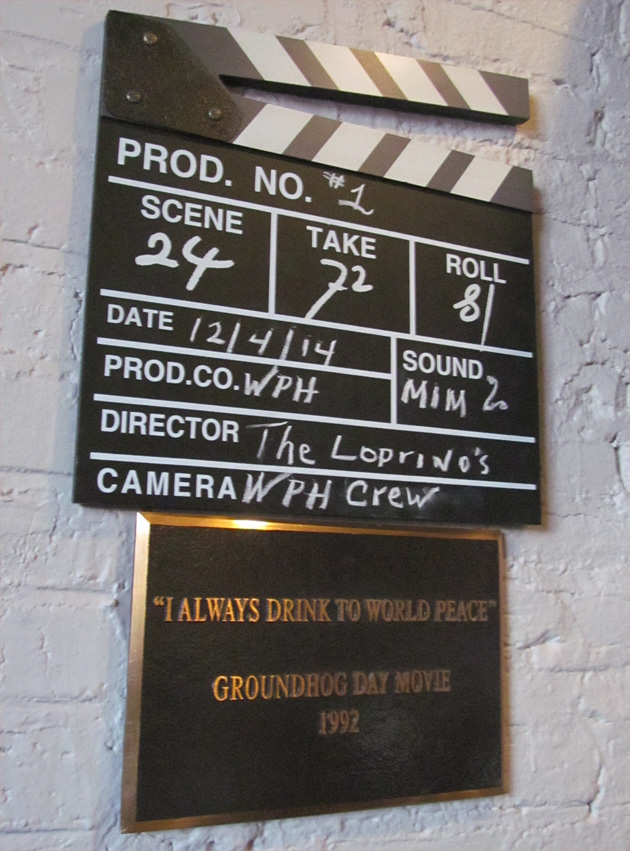

When the movie was shot here, in 1992, Woodstock Square was largely vacant. It had suffered the fate of so many downtowns in that era: People were moving to the newer developments further afield. In fact, lacking viable options for food, the film crew built out a diner in an empty storefront for the movie. After the film wrapped, that diner, the Tip Top Cafe, reopened as a working restaurant. The movie revitalized the town’s confidence in its square, and now the buildings are filled with little shops and restaurants. The Tip Top closed in 2012, but I eat at its replacement, Taqueria La Placita, which serves pretty good Mexican food. From the window of the restaurant, I can see the pavilion in the center of the square. An older couple is dancing there, alone, recreating a scene from the movie. They freeze, mid twirl, and someone takes their photo.

Throughout the weekend I witness similar romantic moments. During the chili cook-off, I talk to Ed Kring of Lombard, Ill., who is in Woodstock with a group of about 20 family and friends. The trip was a surprise for his wife’s 60th birthday, and it had taken him five months to orchestrate. People came from as far as Dallas to see her at Groundhog Days.

By Sunday morning, the sun is gone, and a blizzard is moving in fast. With the roads too treacherous, I travel in by train. Many of my fellow passengers are headed out to Super Bowl parties. When I tell them where I am going, more than once I hear, “When is Groundhog Day, anyway?” An event that is all consuming in Woodstock or Punxsutawney, that lasts for multiple days and is even treated like a major holiday, is a single morning’s footnote to most everyone else.

This year, the festival’s VIP guests are Bob Hudgins, Groundhog Day’s location manager, who leads a walking tour of the filming sites and provides trivia about the making of the movie. Rick Le Fevour, who was Bill Murray’s stuntman, also appears and waves to the crowds before the film screenings.

I call actor Stephen Tobolowsky, who played Ned Ryerson in the movie, to reminisce about the one time he visited. “It was quite the do,” he says, chuckling. He went along for the walking tour, bought a stuffed groundhog (which his cat has since claimed as his own), and stayed in the same B&B where he lived during the filming.

“The thing that surprised me most,” he says, “is, well, you know reality is not the same as movie reality. But it was so festive and fun—it captured the spirit of the movie. It shocked me, how the film reality and real reality had merged.”