Last April I embarked on a road trip around the country. In my 1992 Honda I kept a tent, a sleeping bag, a dozen cans of Bush’s Baked Beans, and about twice as many books and CDs than I needed. Oh, and two cameras. The cameras are important, not because I’m a photographer (I’m not), but because I’m a compulsive recorder. I save notebooks and ticket stubs, postcards and receipts—and I take pictures. The only thing that seems to cure me of this is a city, where I am too self-conscious to label myself a tourist by pulling out my clunky 35-millimeter. And besides, I have friends in the cities—there’s no need to beat back my loneliness with a camera. In fact, I’m probably happiest when I put the camera away altogether. That said, photos to me are like post-it notes: They’re reminders to tell the stories. Here are some of mine.

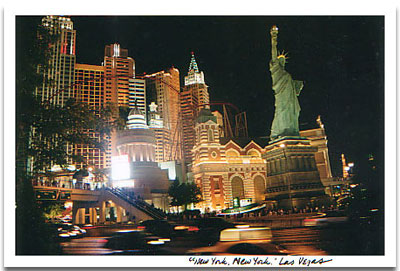

Las Vegas

Films always portray Las Vegas as a dangerous playground for the rich and fabulous. But as far as I could tell, no filmmakers have come closer to the black soul of Vegas than Joe Eszterhas and Paul Verhoeven, perpetrators of the jaw-dropping Showgirls, the story of a sassy and frequently naked farm girl with dreams of being a Vegas dancer. She strips, she talks dirty, she cums like a freight train. Never before has sex been such a turn-off.

And so it is with Vegas, a city so desperate to promote its glitz that it can’t help but seem sad. Sure I marvel at the hotels, the rivers running with chocolate, the Statue of Liberty and the Eiffel Tower—but for me Las Vegas is the world’s best argument for Puritanism. The old people chain-smoking at the slot machines, the girls on the street showing their tits, the drunken frat boys, the all-you-can-eat buffets, Siegfried and Roy. Every time I leave Las Vegas I swear I won’t return. But I do. It’s the same with Showgirls; the film is a disaster, rife with bad dialogue and patently offensive portrayals, but I just can’t stop watching.

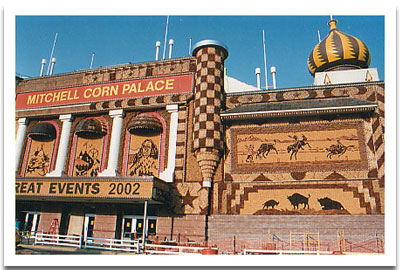

The World’s Only Corn Palace

Every five miles on a bleak South Dakota highway came a sign: ‘Be A-Maize-d!’ Or this one: ‘Ears to You!’ This went on for perhaps an hour, each billboard bolstering my anticipation from a casual curiosity to a five-alarm need. ‘The World’s Only Corn Palace Awaits!’ I drove faster, harder, more reckless: Ear I Come. Corn to be Wild.

The World’s Only Corn Palace (and can you believe there’s only one?) is in Mitchell, SD. A mosaic of black and yellow corn cobs cover its facade—‘What Amazing Ear-chitecture!’—a tribute to agriculture and American kitsch. Inside, vendors crowd a stadium floor, selling corn-cob-shaped candles and windchimes, dolls made of husks, popcorn balls ,and corn lollipops. Curiously lacking: actual corn.

I left empty-handed. Well, shucks.

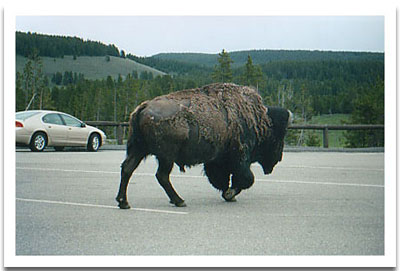

Yellowstone National Park

The buffalo, huge and shaggy, walked through the Yellowstone parking lot. A hundred tourists reached for their cameras.

‘Where’s he going, Mommy?’ asked the little girl behind me. ‘Is he going home?’

‘Maybe,’ she said, clutching the girl around the collar.

We had just looped around the Indian bubbling pots—great blurping vats of boiling mud—when the buffalo began to saunter through the buses and sedans, parting tour groups as he passed. No one went near him, except one giggling young woman who scurried alongside the thing, leaning in and smiling as her boyfriend snapped pictures.

‘She’s going to get us all killed,’ said the mother.

The buffalo just kept walking. He’d seen worse.

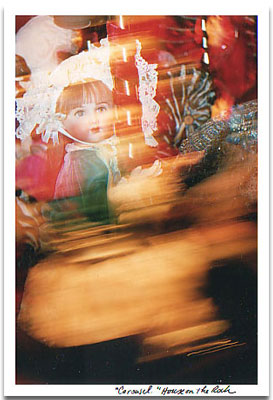

The House on the Rock

In other countries tourists travel for days to visit a cathedral, a mosque, ancient ruins. In Wisconsin I drove two hours out of Madison to find the House on the Rock: 200 acres of eccentricity, like Graceland times 10. True to its name, it is built on a rock and dangles off one side in a bizarre game of architectural Double Dare. But the true feat lies inside, in the two-mile labyrinth of collectibles—vintage cars, coin-operated games, automated music machines—every room dark and empty and tinkling with sound. A carousel ridden by a thousand curly-haired cherubs. A room filled with instruments that play themselves. It was like a ghost-land—cold and creepy and a quarter a pop.

I dropped a coin in a slot and heard it land with a plunk. A hundred mannequins popped open their eyes. Their jaws unhinged, and they began to sing. I left immediately.

The Most Finnish Town in America

Hancock, Mich., is known (in guidebooks, at least) as the most Finnish town in America. The shopkeepers speak Finnish and sell Finnish products—cardamom bread, sauna equipment, and Nokia phones. I’m part Finnish, but that’s never meant much to me besides the fact that no one can pronounce my last name.

‘Christine Lahti is Finnish,’ my dad used to tell me. It didn’t explain things. I had only the most casual sense of my heritage.

That’s part of the reason my dad and I took this trip to the Upper Peninsula, that blob of land across the Great Lakes, 10 hours north from Detroit, where he flew in to meet me. While we were there, my father wanted me to see the Hancock mine—the dark and drippy mine, climate-controlled for a hangover—where my relatives used to work. I don’t like guided tours much; I’m embarrassed by the hand-holding, wearied by the historical spiels. And though I wanted to do this for my father, though he asks so little of me, though I know this ignorance about my heritage is embarrassing and too typically American, I soon grew bratty.

‘Do you want to take a picture of the world’s largest steel hoist?’ my father asked, rubbing my shoulders.

‘No,’ I said, pulling away. ‘I want to take a picture of the stairs.’ I wandered off from the group.

Our guide was a teen girl—blue eyes, ruddy cheeks, dark hair falling over her pierced brow—and she was perhaps the only person there more bored than I. Her eyes skid over the steel hoist, a huge silver barrel that filled the room. She stared out the window.

‘Do you have any questions about the world’s largest steel hoist?’ she asked.

A woman raised her hand. ‘Are you Finnish?’

‘Yes. Terveteloa,’ she said, rolling her eyes and blushing.

I’d just learned that word. It meant ‘Welcome.’

Always After Me Lucky Charms

The Mall of America boasts many attractions—an indoor aquarium, a Ferris wheel, something called ‘Camp Snoopy’—but none captured my imagination like Cereal Adventures. A funland based on everyone’s favorite breakfast food, Cereal Adventures features such unforgettable games as Cocoa Puffs Canyon, a first-person shooter in which Sonny the Cuckoo Bird sprays the world with chocolatey pebbles. Kids crawled through the Cheerios Play Park, a mini-maze of mesh and plastic; I was the oldest customer by a decade.

‘You want to play a game?’ asked one of the employees, desperate for distraction. He pummeled me at Trix Rabbit skee-ball, and afterward, looked to see if his boss was nearby. ‘Three out of five?’

Cereal Adventures also promises a restaurant where you can ‘Make your own cereal!’ That’s not true, exactly, but you can combine three existing brands. I gorged on every cereal my mother forbade me to eat.

‘I’ll take Cookie Crisp…and Cinnamon Honey Toast Crunch…and, uh, Reese’s Peanut Butter Puffs.’

And yes, mom, I did get sick.

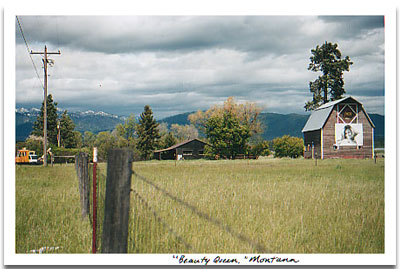

Montana

There’s a certain degree of solitude that resembles insanity. A certain sloughing off of social conventions, when a traveler ceases to bathe, say, or change her clothes, when a traveler begins to pick her nose in public, or sing John Denver songs to a tree. I achieved that degree of solitude in Montana. The fat, purple skies and the marbled mountains and the road, the road, the road are like a drunken episode that only exists in snapshots for me. Montana is beautiful, of course, but my eyes were heavy with beauty by then. I had been spoiled by beauty. ‘Huh,’ I thought as I drove. ‘Another perfect sunset.’ I spent full days alone, running my hands over my shortcomings like a pimple that won’t go away.

So when I saw this barn, I screeched my car around on the highway. Who was this girl? A farmer’s daughter? A beauty queen? A debutante? I drove away imagining her life, which took me out of my own for a while.

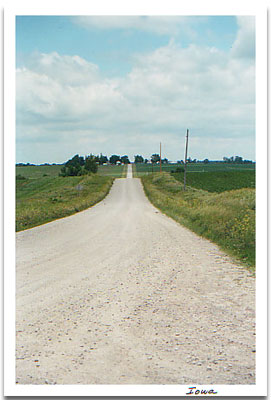

Iowa

I stayed in Iowa with a retired couple, two tree farmers named John and Betty. They woke every morning at 5:00 a.m. to tend the trees—acres and acres of trees—and at night we watched television—a documentary on the disappearing prairie, the PBS show Frontier House. ‘Of course,’ Betty explained, flipping the channel, ‘John loves The Wheel.’

John was a gentle old man, with a big moon of a face, prone to La-Z-Boy recliners and impromptu speeches. ‘The chestnut is a greatly overlooked nut,’ began one. ‘We never should have killed off the buffalo,’ went another. And don’t even get him started on Bush.

‘John, you’re boring her to tears,’ Betty would tease. ‘Have I shown you pictures of our grandchildren? This one’s as beautiful as pie,’ only she had a Southern accent, so she said ‘pah.’

‘She doesn’t want to see those, Betty,’ John would say. And then he’d try to outguess the Wheel contestants.

They had come to Winfield, Iowa—‘a town so quaint they blow the lunch whistle every day,’ Betty told me—after John inherited the family farm. He was a research psychologist working in Illinois—nice suburban life, decades away from his youth spent in the Great Sagging Middle. I can’t remember what prompted the idea—maybe an article or a TV program—but they decided to sell everything to raise trees. It would be their contribution to the earth. Trees. Forty-thousand of them—shade trees and evergreens and, of course, chestnut trees. That was two years ago, and since then they had become experts in soil and oxidation, in the frustrating balancing act of the land.

At the tree farm we slogged along the squishy trail as a dozen tiny frogs leapt off the ground like flies. ‘The frog is an interesting animal,’ John began.

‘She doesn’t want to hear it,’ Betty said, laughing.

‘But I do,’ I said. And I really did.

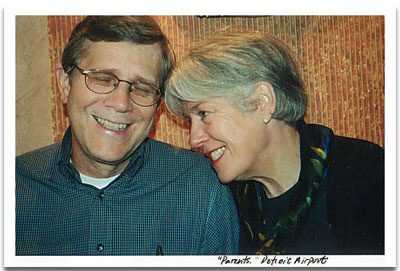

Parents

When I announced my plans for this road trip, my dad told me it was a good idea. My mother told me it was a good idea for someone else’s daughter. For the six months I traveled, we talked on the phone often—dad asking after my car and my computer, mom asking after my health and my loneliness.

Somewhere around Atlanta I told my mom I might keep going. I was sleeping in my car by then, stretching a 20-dollar bill for a week, and like so many travelers who can’t bring the trip to an end, I had this impulse toward inertia.

‘I just feel like I haven’t seen enough yet,’ I said. There was the Deep South. And Florida. And Dollywood.

‘I think I’m ready for you to come home,’ my mom said. And the way she said it, I knew I was too.