In February of 2006 I returned to India, after 15 years away, in search of the past. I gave myself one week on either side of a cousin’s five-day wedding up north in Jammu, the winter capital of the tumultuous state of Jammu and Kashmir—the closest that most exiled Hindus, like my family, can safely get to Kashmir proper. Three weeks: a scant period in a country where a billion things seem to happen every second, where time itself has a malleability like nowhere else in the world.

If I were a real journalist who wanted to seem as though he knew what he were talking about, I might tell you something about India that went like this:

India has roared through adolescence as an independent nation and, like a youthful heir, emerged brazen, cocky, ready to take on the world. Assured of superpower status before 2050, India was the hot topic at last year’s World Economic Forum in Davos, prompting Newsweek to run a cover story (“India Rising,” March 6, 2006) that concludes, “Today it is India’s moment. It can grasp it and forge a new path for itself.”

Then I might say something like this:

On this path, India has a gleam in her eye and a spring in her step. She’s traded in her sari and bangles for a power suit and BlackBerry. The world is watching, waiting, wondering what India will do with her burgeoning wealth, status, and newfound confidence—whether she will lead the way into the new millennium or fall victim to her own, bubbling inner turmoil.

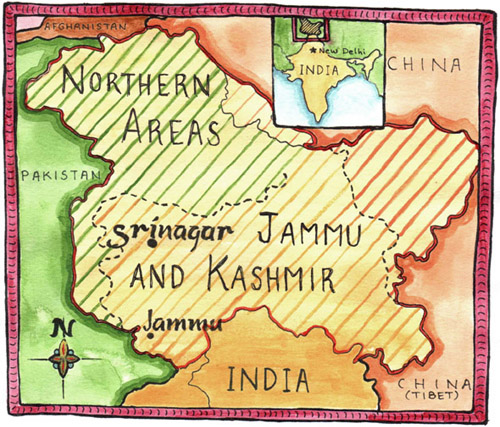

These are the sorts of things people seem to be writing about, anyway. But despite being vaguely aware of this glaring international spotlight, my own trip to India was fueled almost entirely by personal curiosity. The truth is: I’m a fraud. Prior to my trip, I didn’t really understand what was going on over there—and I still don’t, not really. I don’t know anything about economics; last January I could barely remember the names of most of the family I’d be staying with. As one of the Hindu families forced by sectarian violence from the Srinagar Valley in 1990, we Mallas are a diasporic lot, scattered from Jammu to Bangalore and to places as far afield and varied as Britain, Switzerland, Japan, Dubai, New Zealand, the United States, and, in the case of me and my immediate family, Canada. Over the past 15 years, opportunities for visits with my relatives have been few and far between. And, get this: Of all the 30-odd Malla grandchildren of my dad’s dad, Pandit Srikanth Malla, somehow I, of all people, am the last remaining male to carry on the family name.

The drive through Delhi is a startling reminder that, while much about India has changed, on a street level things are about the same as they were when I was last there: filthy. Being Kashmiri has been something I’ve sort of appreciated in a distant, convenient way, something I bring up occasionally to give myself credibility and a manufactured sense of identity. “You don’t look Indian,” people tell me. I’ve got blue eyes and light skin, sure, but “we all look this way,” I assure them, and go on, as though I know what I’m talking about, to detail the history of the Kashmiri Pandits as descendents of Central Asian migrants ethnically distinct from their Dravidian neighbors to the south, blah, blah, blah, namaskar, goodnight.

I don’t speak Kashmiri and have only a cursory understanding of the conflict and very little connection to the culture itself. So, approaching 30 and having not visited in half my own lifetime, I decided to go to India. I went with the hope that something would emerge from the trip to make me feel more confident in being the last hope for future Malla progeny. While the world’s eyes are on India as a nation, I only wanted to know what’s happened to my family, who we used to be—name a cliché, and I probably had it covered.

But when I got to India, I found the past more difficult to track down than I’d imagined it would be.

My trip begins at Jawaharlal Nehru airport in New Delhi, where two men, Raju and Manoj, pick me up and take me back to my aunt’s house in the upscale Vasant Vihar neighborhood. My aunt and her husband are rich; they own the company that provides 90% of the auto glass to Indian car manufacturers and are rumored to be worth close to $80 million. They are away on business for a few days, but Raju, my aunt’s personal assistant, will be taking care of me until they return. Manoj is one of two drivers in their employ in Delhi (the other is Kishin); there is also a sentry in a beret who opens and closes the gate, two cleaning ladies, a cook, and a boy Raju refers to as “the Boy.”

The drive through Delhi is a startling reminder that, while much about India has changed, aesthetically, at least on a street level, things are about the same as they were when I was last there: filthy. Part of the problem seems to be plastic; signs everywhere begging people to “Say no to plastic bags!” seem to be ignored, if the piles of polyethylene garbage everywhere are any indication. Despite embracing the disposable products of the West, India has made few infrastructural moves to deal with the subsequent volume of waste. I remember my family almost obsessively reusing glass containers; now, instead of advising people to recycle, plastic bottles only suggest, meekly, Please crush.

My aunt’s place is not the luxurious mansion I remember; it is much smaller, slightly derelict, bordering on shabby. The paint everywhere is peeling, water damage spreads in a deep bruise over the lower half of one of the walls in the guest bedroom, and all of the light switches in the house are marked with the grubby fingerprints that seem to surround every Indian light switch, trailing in gray smudges up the wall as though someone (or 1.2 billion someones) has been blindly stabbing at the area in the dark.

We swerve into the other lane, sending a garlanded Tata truck, horn blaring, into the ditch. In the rearview mirror, smoke billows from the truck’s engine. Is anyone dead? Does it matter? In the dining room is the Boy, peeling Styrofoam lids off my supper (the cook is off for the night). After some prying it turns out the Boy has a name: Vijay. Later, I discover that my aunt is grooming young Vijay to replace Raju as her personal assistant, and Raju’s attitude toward him makes a bit more sense. Vijay is 17, stylishly dressed, computer-savvy, teaching himself English. Raju has the standard-issue moustache and pot-belly of the Hindu middle-class male, and a hairstyle straight from a 1984 Top Cuts catalog. (“That one! The saucy-but-manly bouffant on page 28!”)

After dinner, Raju hovers in the doorway of my room while I root through my bag for my toothbrush. Is he waiting to tuck me in? “For eating tomorrow, Mr. Pasha?” he finally asks. “Domino’s? KFC?”

“Indian food is fine,” I tell him. “I can get that stuff in Canada.”

Raju looks disappointed. He closes the door without even saying goodnight.

The next morning Raju wakes me bright and early to go sightseeing. Manoj drives. Our first stop is Qutb Minar, a 13th-century Islamic compound with a really tall tower on the outskirts of the city. Until 25 years ago, when a group of schoolchildren were trampled to death in the stairwell, people used to be allowed to climb to the top. Now, you can only take pictures from below. The tower leans a bit, something Raju fails to capture in the wonky photographs he insists on taking with my camera. When he asks me, “How many megapixels?” and I have to admit, “One,” he snorts and hands it back to me. “I will be in the car,” he says, and is gone.

After lunch in Connaught Circus, Manoj drives us to my aunt’s farmhouse in the country. On the way, something immense and frightening flaps across the road—a pterodactyl, I’m pretty sure—and we swerve into the other lane, sending a garlanded Tata truck, horn blaring, into the ditch. Manoj straightens the car; we carry on. In the rearview mirror, smoke billows from the truck’s engine. Is anyone dead? Does it matter?

The farmhouse is the sort of place I imagine graces most high-end vineyards in the Napa Valley: gabled roof, white-washed everything, sprawling grounds replete with a giant stone fountain plonked into the middle of the lawn, more estate than home. On a patch of land behind the swimming pool, what Raju explains as “Kashmiri food” is growing in neatly tended rows. Apparently, two things perturb exiled Kashmiri Pandits like my relatives: the “situation” back home and where to buy kohlrabi with the leaves on—they are usually removed by grocers outside of the Srinagar Valley. My relatives in Delhi have solved this by growing their own, along with an array of other hard-to-find Kashmiri vegetables: monge, haakh, gogge, sochal and kashir palak. What they can’t eat is distributed to the few Kashmiri families in the surrounding area. The rest, I assume, is either discarded as waste or left in the streets for beggars and dogs.

After Manoj drops me back off at my aunt and uncle’s house in the city, Vijay brings me a beer while I watch NBA highlights on satellite. Being at the farmhouse with no one around but a few gardeners, security guards, Raju, and Manoj is a strange experience. I feel like a tourist in a place that should be a refuge from Delhi’s hustle—I’d expected this place to feel, even in some intangible way, like home. Instead I am perched in a lawn chair while the sun sets and the fountain perched in the middle of the lawn is turned on for my amusement: lighted in pastel shades, the water spurts up a nozzle and splashes down, runs in channels back into the centre, then shot back up through the nozzle at the top, around and around and around.

“Beautiful, isn’t it,” whispers Raju, kneeling beside me in the grass.

“Yeah,” I tell him. “It sure is.”

After Manoj drops me back off at my aunt and uncle’s house in the city, Vijay brings me a beer while I watch NBA highlights on satellite, and then excuses himself to go home for the night. Sitting there, I realize that I have been in India 24 hours and, while Raju and Manoj have been performing their best efforts as guides, I have yet to see anyone I’m even vaguely related to. The big old house suddenly feels empty and echoes with the frenetic play-by-play from the dude on ESPN. This isn’t why I’ve come here—to traipse around to tourist attractions and bask in my family’s weird wealth. Where are the personal epiphanies, the sudden understanding of myself I’d expected—fuck, counted on? The only thing close to understanding Kashmir has been gazing briefly at a bunch of collard greens. Instead, I’m drinking piss-warm Kingfisher alone in my aunt’s crumbling mansion, watching Gilbert Arenas go for 45 against the Orlando Magic.

That’s when I notice the clock in the living room. Since arriving, I’ve been struggling to tell time on it, a problem I attributed to jetlag or just being dumb. But, sitting there, I finally figure out what the problem is: The clock runs backward. For some reason the numbers ascend counter-clockwise, the 1 to the left of the 12 at the top, and then the 2, and so on. This strikes me at first as bewildering, then hilarious, and, finally, somehow apt.

Before I go to bed, Raju calls. “Tomorrow you get up early, Mr. Pasha. We’ll have a big, big day. Day after, Auntie and Uncle come home.”

“OK,” I tell him. I’m suddenly very, very tired. “See you in the morning.”