For my last night in Delhi before heading north to Jammu, my cousin Pinky has promised to take me to the sleek lounge of a five-star New Delhi hotel. Hotel bars are where Indian urbanite hipsters (and anyone else with money) tend to do their drinking. Rising above the bustling poverty of the Delhi streets near my aunt’s house, a billboard advertises what must be a similar place; a font reminiscent of robots spells out the club’s name and a series of instructions: Chill, Dance, Relax, Meet, Chat. I imagine the city’s beautiful people taking this process very seriously. “Yaar, you ass, you’re not chilling correctly—lean back and mellow out more, like this.”

First thing that morning, my aunt, Kanta, and uncle, Mr. Labroo, return home from their business trip, wherever it was. They are exactly as I remember them—except maybe a bit more tired-looking, a bit grayer, a bit more hushed. I like my aunt; she’s very kind and makes me feel tall. Mr. Labroo has something of a latter-day Marlon Brando about him and wears a lot of green suits. Immediately, he wants to take me to Gurgaon, a suburb of Delhi that has in the last few years been developed into an ultra-modern business park and hotbed of condominium property. This is where the Delhi office of his glass company is located, way up on the top floor of a high-rise tower.

In the lobby, I am introduced to a group of profusely bowing underlings. “This is my wife’s nephew,” Mr. Labroo tells them. “Namaste,” I say. “Hello,” they all reply—except for one guy in a fauxhawk and thumb-ring, who offers a very cool, “Yo,” and traps me in a baffling rendition of a soul-shake. At Asahi India, everyone speaks English; not a word of Hindi is uttered inside the building.

Once in Mr. Labroo’s office, I am shown into an adjoining lounge with a flat-screen TV and a lumpy leather couch. While my uncle makes deals on the phone and orders me a lunch I don’t want, I look out from a floor-to-ceiling window over Gurgaon: the skyscrapers and network of new highways, the condos, the shopping malls like giant, Floridian spaceships, a jeans store called Pantaloons. Everywhere, cranes and construction crews are adding to the urban sprawl.

In the shadow of all the office towers is a cluster of tarpaulin huts where crouching women sweep the dust. At one end of the shantytown, a dog sniffs and pisses on a pile of garbage being picked through by naked children; at the other, a shirtless fellow washes himself with a bucket of brown water.

That afternoon, one of the family’s chauffeurs, Kishin, drives Kanta and me to visit my cousin, Sonny, 15 or so years my senior. When I was a kid, Sonny was one of the few Indian relatives who would indulge my insatiable appetite for sports; an avid cricketer and soccer player, he represented a welcome chance to run around and play. Now, Sonny is a higher-up in the glass company; he and his family live in a sort of gated community on the outskirts of town.

A team of uniformed guards (one to blow a whistle, two to open the gate, one to salute us as we pass) lets us inside the walls of Sonny’s home, a massive, sprawling Beverly Hills-style compound featuring a full soccer field replete with painted lines, corner flags, and regulation goals. Two golden retrievers greet us, beautiful and bounding about, providing a striking contrast to the mangy mutts sniffling about in the gutters outside. Compared to my aunt and uncle’s ramshackle house in town, this place seems opulent, on the cusp of something new and modern and exciting.

I sit in the garden with Sonny and his alarmingly attractive wife (whose social circle comprises mainly cricket stars and Bollywood starlets) and my aunt, and we have wine—Indian wine, a prizewinner in some recent international competition. Sonny gets talking about India’s newfound wealth; it is a subject he obviously enjoys discussing.

At Asahi India, everyone speaks English; not a word of Hindi is uttered inside the building. Sonny’s perspective is of one who has enjoyed riches before they were accessible to so many. “These people making money don’t know what to do with it,” he explains. “They spend and spend, with no social conscience, no ethics. What they don’t realize is that the government ignores the people, so it is up to us—” and it is clear by the sweep of his hand across his property who this “us” refers to “—to use our wealth to help the country. GDP isn’t enough. The health-care system, for example, is a mess.”

Later, my aunt tells me that Sonny has spearheaded an initiative that involves a train of doctors driven around the country performing free eye operations on the poor: one car for surgeries, one for recuperation and one offering free meals to villagers, sick or not. Kanta, for her part, has opened a school for girls in northern India, and she dedicates a substantial amount of her time and wealth to help feed and clothe Hindu refugees from Kashmir. When she tells me about this, I’m shocked—but when I press for more information, she dismisses the subject with a wave and clink of a bangled wrist.

Still, this refugee business has me confused. I’ve always assumed that all Kashmiris were like my family—maybe not the exorbitantly wealthy side of my family I’ve been exposed to since arriving in India, but educated professionals, people with nice homes and a car or two and very good, clean teeth.

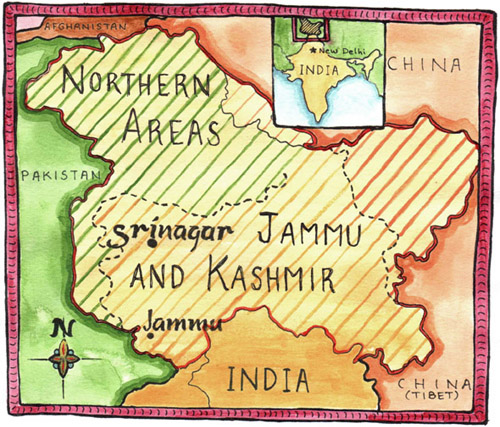

After dinner back at my aunt’s place, Sonny’s sister Pinky fetches me with her driver and we hit the Delhi nightclub scene. Pinky, who splits her time between homes in London and Delhi, is a nationally graded classical singer who often records at a studio in Srinagar in the heart of the Kashmiri Valley. She has protection when she goes, a team of bodyguards provided through entertainment industry and government contacts; without this security, who knows what might happen. With no inroads so far with anyone else, I look forward to finally talking to someone about one of the main reasons I’d come to India—someone who, unlike anyone else in my family, still makes visits to our ancestral homeland.

Instead, at the lounge we set up shop in a corner booth, order complicated drinks, and within minutes find ourselves half-drunk and transfixed by a beautiful, dancing white woman. There is no dance floor in this place (although there is a backlit waterfall and a lot of mirrors), but this woman—more of a girl, really, maybe 19, and boasting that severe brand of beauty particular to former Soviet states—has created one: She slinks and shimmies, and Pinky and I and all the other brown faces sit staring, enraptured.

At the table beside us, the three men who I imagine to be the girl’s companions are speaking what seems to be Russian. These men are dressed in pinstriped suits and alarmingly pointed shoes; all have hair slicked back wetly against their scalps. They look dangerous; they drink their beers methodically, peering around the bar with an intensity that seems almost predatory. Is one of these men the girl’s lover? Or dad?

Then something happens. We aren’t quite sure what it is, but two of the men stand, button their jackets and stride purposefully across the lounge, where they sit down in a booth with two middle-aged Indian businessmen. Their remaining comrade stays at the table beside Pinky and me. He drinks his drink. “Should I ask him to join us?” I wonder, whispering. Pinky shakes her head. “Are you crazy?”

“That doesn’t happen here. Not like in places this. At least it didn’t used to.” In the meantime, a young Indian couple has gone up and interrupted the beautiful girl’s dancing. They want to have their picture taken with her. She complies, smiling; the flash flashes and the couple retreat to their seats, already checking the picture on the camera’s display screen, beaming.

I look over at the fellow beside us. He catches my eye, nods. A scar slices palely across his forehead and down along his nose.

“So,” I say, my courage bolstered by Kingfisher beer, “where are you from?”

“My friends and I come from Ukraine.” His voice is soot shaken about in a coffin. “But we have brought her—” he gestures toward the girl “—from Russia.”

Then the other two Ukrainians are back, now with the Indian businessmen in tow. All four of them stand over the table, muttering. The seated man summons the Russian girl with his index finger. She comes over, is given instructions, nods, and then takes one of the Indian fellows by the hand and leads him out of the bar, into the elevator, and upstairs into the hotel. Twenty minutes later they return, and it is the other Indian businessman’s turn with the girl.

Pinky and I finish our drinks in silence. After we order another round, she tells me, “That doesn’t happen here. Not like in places this.” Then, as a sort of sad, nostalgic revelation, she adds, “At least it didn’t used to.”

At some point after midnight, Pinky’s driver drops me off at my aunt’s house. I stand on the street and wait for the guy who opens the gate to do his job. “Well, I’ll see you in Jammu for the wedding,” says Pinky from the backseat, the car door hanging open.

I realize that I’ve been too busy sightseeing and caught up in New India that I keep forgetting the real reason I’ve come here: Kashmir. My only glimpses into the past have been monuments, those safe, museumized relics of history that have become a sort of Indian brand. Otherwise, I’ve been immersed in the strange fantasy-world of my family’s wealth; while the rest of India shuffles along on its knees I’ve been whisked between mansions and ranches and high-end nightclubs, all of it somehow barreling headlong toward the promising future.

With the car door hanging open, Pinky mentions that she is going to be heading to Srinagar after the wedding to do some recording. “You can probably come along if you want,” she tells me.

My thoughts of Kashmir to this point have ranged from non-existent to fleeting; going there hasn’t even crossed my mind. Before leaving Canada, my instructions from my dad were strictly, “You can’t go, it’s too dangerous.”

“Kashmir?” I say. I feel frightened already.

“Sure,” says Pinky, reaching over to close the door. “Just let me know.”

Then the door closes and the car takes her away, and I am left standing alone in the street.

On a trip back to India, our author sees the shining new face of the country’s idealistic business elite—and also the not-so-shining parts. The third installment in a series of travel essays.