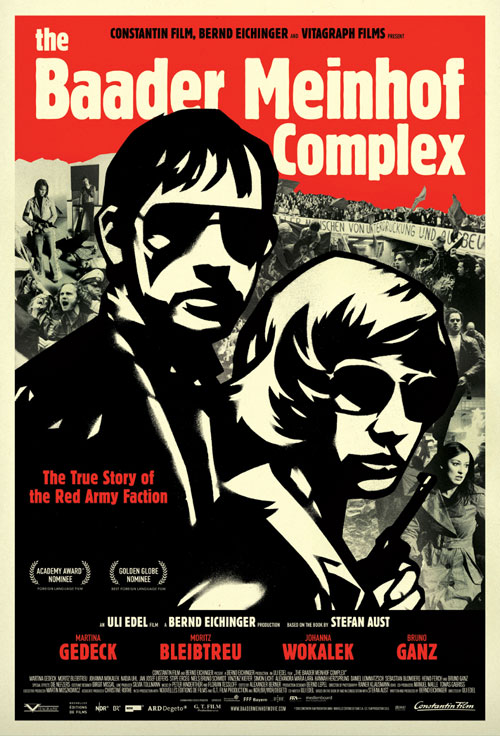

There is a scene in the 2008 film The Baader-Meinhof Complex—a dramatized history of 1970s left-wing violence in Germany—in which an assassin on the back of a motorcycle riddles a car and its three passengers with machine-gun bullets. The car, sitting at a stoplight, is carrying federal prosecutor Siegfried Buback, an aide, and his driver. The first two die immediately, but the driver manages to open his door and tumble out as the car rolls onto the sidewalk. The motorcycle driver pulls alongside, the assassin shoots the driver again for good measure, and the pair rides off.

Though the April 1977 crime has never been solved, credit was taken by the Red Army Faction, a leftist paramilitary organization made up of middle-class baby boomers; like their American co-generationalists, they were the products of unbelievable affluence in the postwar years. It is not the most violent scene in the movie, but for me it was the most affecting: The assassin’s face hidden behind a tinted helmet shield, the cold professionalism of the hit. And its location in Karlsruhe, the seat of the West German federal court and a byword for Teutonic law and order. But above all, knowing that the assassin is not some mob hitman or CIA spy, but a middle-class, twentysomething German, someone who could just as easily be tipping back a pilsner or shooting pool with friends at the corner bar.

The assassin is not some mob hitman or CIA spy, but a middle-class, twentysomething German, someone who could just as easily be tipping back a pilsner.I saw The Baader-Meinhof Complex for the first time a few weeks ago, but the Buback assassination is on my mind these days for another reason: In late August, German police arrested former RAF member Verena Becker, claiming to have new evidence linking her to the killing. In May 1977, the then-24-year-old was arrested after police chased her car down a dead-end street; she shot a cop in the process and was sentenced to life in prison. In the trunk of her car, investigators found the gun used to kill Buback, but at the time even stronger evidence seemed to point elsewhere. Becker received a pardon in 1989 and, from then until August, lived under an assumed name in the Berlin suburbs. Police now say traces of her DNA found on letters sent afterward to German authorities show that, at the very least, she was intimately involved in the operation. She is now back in prison, awaiting trial.

The story knocked the upcoming national elections off the front page for days, only months after another RAF-era shocker was uncovered: The cop who had killed a demonstrator at a 1967 protest and sparked ensuing decades of far-left violence was in fact a valuable agent for the East German Stasi. That revelation rocked Germany for weeks; it was still a topic of conversation in late summer, when I arrived for a two-month fellowship at the newspaper Der Tagesspiegel. It’s hard to convey just how much the RAF and the 1970s radical left still matter in Germany. America had its own advocates of left-wing violence in the 1970s, but the scene in The Baader-Meinhof Complex underlines how much worse things were in Germany. Bernardine Dohrn may have gabbed about offin’ pigs, but it’s hard to picture her on the back of that motorcycle.

In the United States all but a few die-hard culture warriors see Dohrn, the Weather Underground, and other outbursts of the 1960s radical effervescence as near-ancient history, if not historical footnotes. With the first post-boomer president now almost a year into his first term, it’s harder and harder to make the case that the ‘60s still matter. Even most baby boomers don’t seem up for the fight anymore.

It’s different in Germany. As in France, being an Achtundsechsiger, or “‘68er,” is a badge worn with pride. Even the worst of the RAF’s actions are debated, if not supported, at boomer-age dinner parties. Proponents say that the movement may have gone too far at times, but that the central goals—ridding the nation’s leadership of ex-Nazis, expanding opportunities for democratic expression—are unassailable. Critics, like the historian Götz Aly (himself an Achtundsechsiger), say they use it as camouflage for their upper-middle-class lifestyles; as long as doctors and lawyers stay true to the cause rhetorically, they can morally afford to wear Prada and drive a Porsche. In America, boomers salve their conscience by shopping at Whole Foods; in Germany they do it with Rudi Dutschke posters.

Poke around Hyde Park long enough and you’ll find people like this in the States, too; visit Berkeley and you’ll have a hard time avoiding them. But the magnitude in Germany is simply, overwhelmingly greater, to the point that the tumult of the late ‘60s and 1970s is still a part of everyday political life. In the film a midlevel official mentions that 25 percent of young Germans, some seven million people, sympathized with the RAF in the mid-1970s. Many still do. In 2007 the government granted clemency to Brigitte Mohnhaupt, an RAF leader from its most violent period—good evidence indicates she coordinated at least three high-profile murders in 1977 alone. Mohnhaupt was arrested in 1982 and had been sentenced to five consecutive life terms in prison. Though the police union and law-and-order conservatives opposed the clemency, scores of left-wing politicians and journalists supported her, arguing that she deserved a “second chance.”

Such sympathies are unimaginable in the United States, where a casual relationship with a child’s-play ex-radical like Bill Ayers became a major right-wing talking point against Barack Obama. In America, the near-complete lack of a radical left makes it that much easier for the right to demonize Obama and the Democrats with surreal charges of “socialism” and “Maoism”—the words have no meaning in the States, so they can be used to mean anything.

But the radical left is alive and well in Germany. In last month’s elections, the leading far-left party, the Linke, won 13 percent of the vote. Much of their base lies among the nostalgics of the former East Germany, but they picked up surprising support from still-radical-after-all-these-years boomers in the West.

“Fuck the system” may be a great song lyric, but it’s not much for a political platform.And then there are the ranks of semi-professional protesters, squatters, anarchists, and gutter punks who, according to police, have been responsible for more than 250 late-night car-burnings in Berlin this year. Most of them are in their teens and twenties; hardly any stick around the scene past 30. They gather in Hamburg and other cities for seasonal, pre-planned riots, in which protesters attack cops and cops beat back protesters and some people get concussions and several get arrested, all in the name of increasingly vague social and political causes. “Violence is a way of achieving our aims,” one young protester told The Local, an English-language Berlin news site. “We do not accept that the state has the monopoly on violence, and it is our aim for there to be social unrest.” The problem is that no one knows what those aims are; “fuck the system” may be a great song lyric, but it’s not much for a political platform.

In Berlin you can still see young people dressed as ‘70s-era British punks—mile-high mohawks, leather jackets stuck through with oversized safety pins, Doc Martens. Thirty years ago, the look was frightening; today, it’s just so… passé. People from the Achtundsechsiger generation see these people, their children—or even grandchildren—and shake their heads. “In our day… ” they tsk-tsk. “What do they want that we can’t give them?” It rarely occurs to them to wonder whether their own parents said the exact same thing.