On the drive north from Delhi I try to decide what I will be, once we get over the border into Jammu and Kashmir state. During my visits as a kid, this of course had never been an issue: I was very clearly my father’s son and traipsed along behind him with my Gameboy in one hand and an Amar Chitra Katha comic in the other. I’ve heard advice that being a tourist in Kashmir is safest; others say that identifying as foreign could encourage kidnappers. I could probably pass for a local, I figure—although there would of course be that pesky issue of language. (A local mute, maybe. Or one of those elusive Kashmiri mimes?)

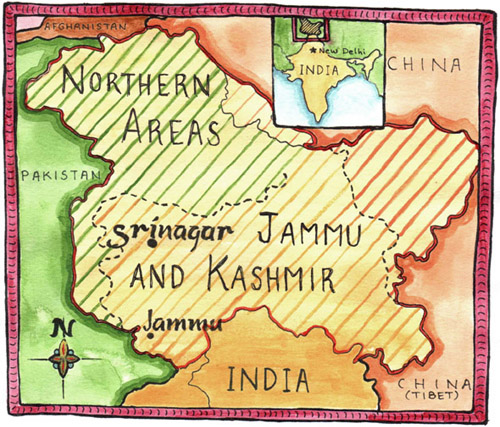

Of course, there is still no distinct plan to head into Kashmir proper. Jammu, the state’s winter capital, is 300 kilometers south of the summer capital, my family’s hometown, Srinagar; it has become something of a refuge for Hindus exiled from the Valley since things got really hectic back in 1991. But, despite its proximity, Jammu is not Kashmir; the closest I can compare it to is camping out in the parking lot of Yankee Stadium, following the game by the roar of the crowd inside.

The family I know best in Jammu consists of my dad’s brother, Jawahar, and his wife, Santosh; until her death when I was in my last year of high school, my grandmother lived with them too. My cousin Manisha, the one getting married, now lives in Bangalore; Manisha’s sister Mona and her husband make their home in the United Arab Emirates. Jammu, the dusty, ugly, stiflingly hot “winter capital” of J&K state, is a stark contrast to the Kashmir Valley—regarded by many, and remembered by my family, as “the most beautiful place in the world.” But this is the closest our family can get to the land of our ancestry, and, for the sake of Manisha’s wedding (an intensely traditional, five-day affair), the best we can do.

My aunt, Kanta, and I leave for Jammu in the middle of the night with Kishin as our chauffeur. The drive, through the breaking dawn, proves terrifying; sleep is an impossibility. Kishin’s horn is a steady, bleating pulse punctuating the tick-tick-tick of highbeams as we tear up behind lorry after lorry, each eventually sliding over to let us pass and occasionally revealing another lorry bearing down on us from the other direction.

Thanks to the influx of new money, one of the Indian government’s recent national incentives is a more fully developed network of highways around the country. These are being done in stages, however, so we alternate between sections of smooth motorway and the treacherous rubble of roads either under construction or, at this stage, completely ignored. Often there are huge potholes we either have to swerve around or barrel over and into and through. At one point we pass a Tata truck whose front axle has been torn from the undercarriage in one of these potholes. While the driver yells into his cellphone, the truck sits in the middle of the road like an elephant slumped to its knees.

We make our way into Punjab and the sun rises. A few hours later we reach the border to Jammu and Kashmir. I expect an ordeal, and brace myself for intensive questioning and potential gunplay. What actually happens—a leisurely wave-through more reminiscent of a tollbooth operation than the boundary into one of the most violent regions in the world—is a nice surprise.

But my relief fades a few kilometers down the road, where we encounter a military checkpoint. We pull up to a barricade and men brandishing machine guns surround the car. My aunt seems unperturbed. She calmly rolls down the window and starts talking in a subdued voice. Kishin stares through the windshield at the open road ahead.

A soldier opens my aunt’s door and jerks his gun in a get-out-of-the-car motion. Another soldier taps my door with the butt of his rifle. I roll down the window. His nametag says Aziz—a Muslim—and his moustache is so neatly clipped it looks glued on. “Are you a Kashmiri?” Aziz asks me in English. I look to my aunt, now standing on the roadside, handing over her purse. What is the right answer?

Kishin’s horn is a steady, bleating pulse punctuating the tick-tick-tick of highbeams as we tear up behind lorry after lorry. “Identification!” barks Aziz. The gun hanging over his shoulder has plastic bits on it; it looks like a toy, almost. “Identification!” Aziz commands again, leaning into the open window to look around the car. “It’s in the back,” I stammer, “in my bag.” “Search the boot!” he orders, and two other soldiers set to it. “Where are you from?” he asks, eyes narrowing. “Canada,” I manage. “I’m Canadian.”

Then I hear my aunt laughing. The officer questioning her turns to the others and announces, “She’s a Kashmiri,” and suddenly the search is abandoned. The soldiers lower their weapons. They bow in a jovial way; a few shake Kanta’s hand. Her purse is returned. Aziz opens the car door for her and says, “Welcome home, Auntie,” as she climbs up into the seat. With waves and more smiles, we are ushered through.

I am relieved, but my fear is, of course, based in ignorance. What I know about the situation in Kashmir is embarrassingly little, and can be summed up in a few sentences: In 1947 the country was partitioned during Independence, and Kashmir’s Maharaja refused to join India rather than Pakistan; after several outbreaks of sectarian violence, which include an invasion of the Pakistani army, the state was divided between the two countries by a ceasefire line. Ever since there has been an ongoing conflict over the “disputed territories” and the region has become a flashpoint for Indo-Pakistani tensions, heightened in the past decade by the emergence of both nations as nuclear powers.

Islamic militants have made it nearly impossible for Hindu Brahmins, Kashmir’s ruling class for most of its history, to live in peace; assassinations, kidnappings, and bombings occur all too frequently, as do often excessively retributive strikes from the Indian army. The most tragic thing, according to my dad, is that most Kashmiri Muslims would happily live in peace with their former Hindu neighbors. While certain formal divisions remained, as kids he and his siblings used to count among their close friends in Srinagar a number of Muslim families. Any present acrimony is a result of the import of soldiers of the mujahedeen who are trained elsewhere—Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran—and shipped to Kashmir to join the war of liberation.

How this all affects me, being here, I’m not entirely sure. All I have to go on are my dad’s warnings and vague notions of danger. I do know that Jammu is a hotbed of terrorist activity and, apparently, under tight military control. But my suspicion of Aziz, as we pull back onto the highway and continue our journey north, has me feeling guilty. This is a guy no doubt as committed to peacefully securing the region as any other patriotic Indian—Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, Jain, Jew, whatever. And his beaming reception of my aunt speaks more to my dad’s memories of communal harmony than any of the sectarian discord I’d expected to exist between Muslims and Hindus.

But then, at midday, we make it to Jammu. At every corner is a sandbagged bunker stationed with police or soldiers, or both, guns poking out through strategic turrets. We pull up to a traffic light and in front of us, perched on the rear wheel-guard of an idling motorcycle, is an officer sighting pedestrians along the barrel of his rifle. Armed guards patrol the streets. Military convoys—those parades of olive-green, canopied lorries—stall traffic as they go grumbling around town, the truck-beds lined with army men staring out morosely as they rattle around inside.

“The last time I saw you, you were playing with toy trucks in the garden,” one lady, maybe an aunt, announces while she clutches me to her bosom. My uncle Jawahar’s house, a two-level concrete block, is across town, and when we arrive preparations for the wedding are already under way. The place teems with people—relatives, neighbors, priests, whoever, with more on their way—all bustling purposefully around while I stand with my luggage in the garden. This is where as kids my cousins and I used to play; now, two cooks hired specially for the wedding have set up a tent where they chop mutton into bite-sized chunks and toss them into a sizzling skillet.

After wandering around for a bit, I find Manisha upstairs getting her arms and legs decorated with henna by two dark, silent women. It’s been 15 years, of course, since I’ve seen my cousin. I remember her as an enthusiast of coloring books and badminton. Now she’s 26 and is some make of engineer or doctor or computer something. I hover nearby, unsure what to say. “Excited?” I ask. She shrugs. “Just tired.”

Back outside, Kanta leads a charge of stout middle-aged women who descend on me with puckered lips and saris flowing. Some I recognize, others I have no clue about. “The last time I saw you, you were playing with toy trucks in the garden,” one lady, maybe an aunt, announces while she clutches me to her bosom.

My sister, Cara, who with her boyfriend, Yonnas, has recently moved to Bangalore to teach outsourced telemarketers to sound less Indian, will be arriving by train later in the day. I offer to meet them at the station, but Uncle Jawahar isn’t having any of it. “This is a terrorist state,” he explains. “Foreigners may be killed.” By whom, I ask him, and he tells me, “By anyone—police, militants, thieves, even locals who think you look suspicious. Things are different from when you were younger. Now you can trust no one here.” I think about Aziz and wonder if my uncle, who has lived here most of his adult life, is overreacting or legitimately concerned for my safety.

Jawahar is off to assign a cousin or neighbor or someone the duty of picking up Cara and Yonnas and dropping them off at their hotel. I find myself standing alone in the garden watching the cooks peel potatoes and chop lotus stems. Even the crush of aunties has abandoned me, gone to the market to get some guavas, which were apparently my favorite fruit as a child—and perhaps still are.

Left alone for a moment of peace—with no guns pointed at me, no relatives to embrace, no screaming car horns and constant threat of death—the smell of Jammu hits me: Shit. Outside the sewers run open along the streets, carrying streams of black sludge from house to house and down to the river. Finally, here is something that seems to have remained from my visits to India as a kid. I breathe the smell in, deeply.

That this is my first brush with tangible familiarity in this place, where I spent at least a month every other year up to the time I was 13, speaks volumes. When I was younger and used to visit I was oblivious to any threat of violence. I played and ate and slept, watched Hindi movies with everyone in the evening and tried to figure out what my grandmother was saying to me the next morning at breakfast. Fifteen years after my last visit I now feel some awareness of what is going on in this place. The tension is palpable. But, ultimately, I remain as ignorant as I was back when I was pushing dinky cars around the yard: I don’t really understand, and I can’t take on a task as simple as picking up my sister in a taxi from the train station.

Along bumpy roads and past intimidating border posts, our author heads north for his cousin’s wedding and discovers safety might be just a state of mind, in the fourth installment in his travel journal.