You’ve written about your childhood interest in Niagara Falls, that you knew that someday you’d honeymoon there or go over the falls in a barrel. Has either thing happened?

Rebecca Bird:No, although I finally visited Niagara Falls on the way to see friends in Toronto a couple years ago, and it was fairly thrilling, a little unreal.

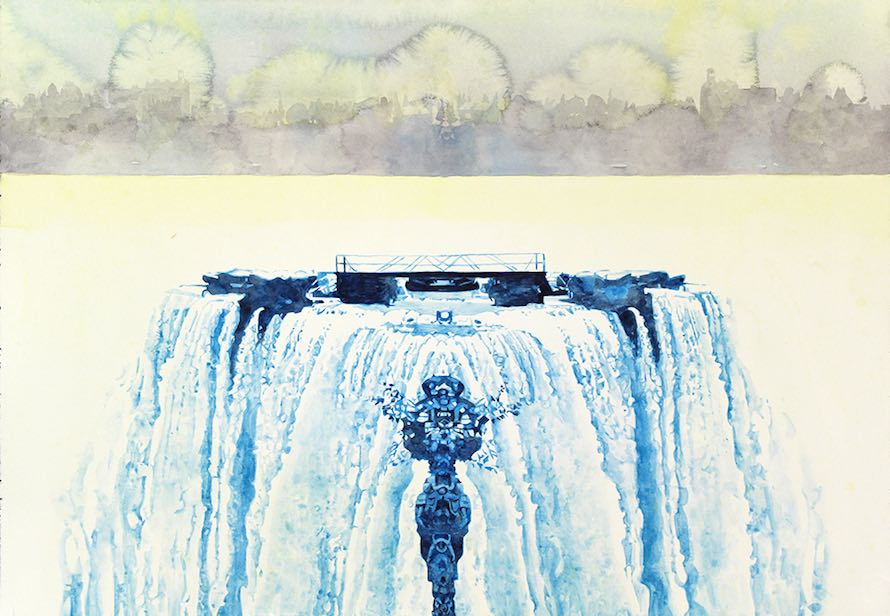

I think painting Niagara Falls has been less about a real or personal experience than about the ideas attached to a place that you don’t have to have visited to know.

What I realized while working with this imagery was, I’d always taken for granted Niagara Falls as a symbol of the perfect unattainable romance, or this death-defying feat of going over the falls as a stunt. It became a window into the kinds of expectations you have for your life when you are a child—the things you think you’re supposed to do, or the dangers you expect you may face. Those two ideas about Niagara Falls were ideas about growing up, that things could go perfectly and correctly, or somehow go terrifying wrong. And neither of them in retrospect were realistic expectations, they were old ideas that were still around, leftover from the last century but still present enough in the culture to be familiar to the average person. I think I saw these two images in Bugs Bunny cartoons, although I can’t find them on YouTube now.

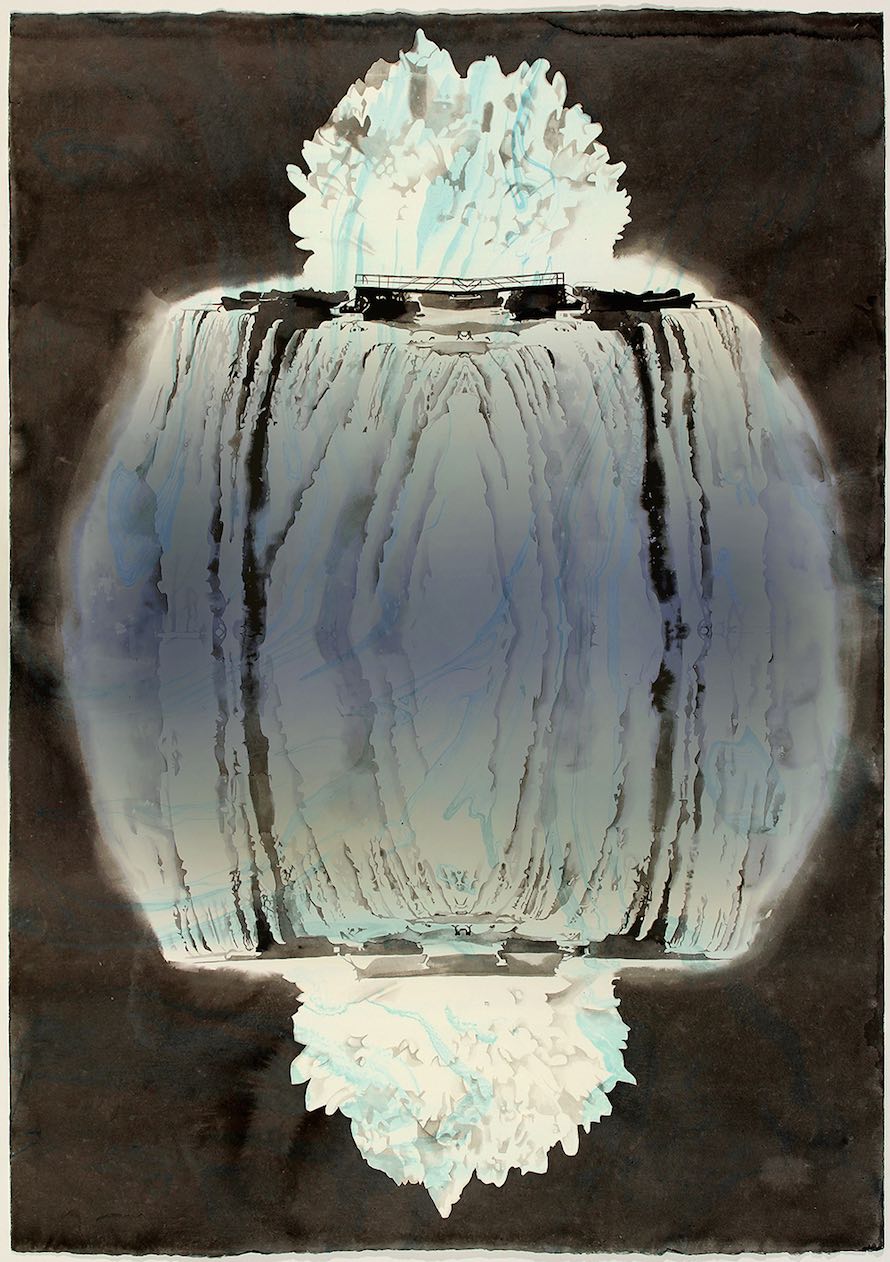

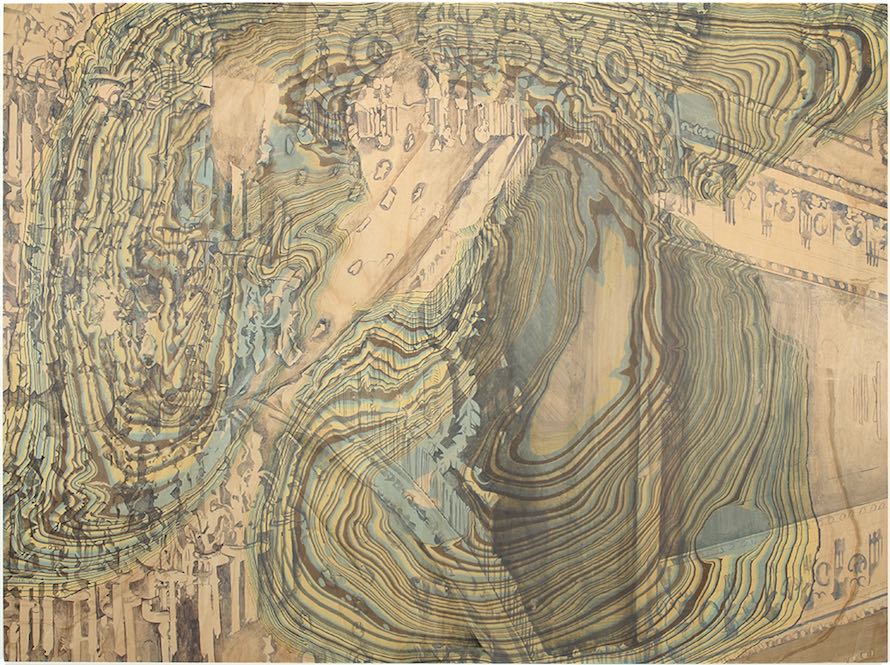

Niagara Falls had cropped up in my work a few times, as an ironic image, then I found an old 1910 book of photos of the falls, and eventually began this series of works based on photos of Niagara Falls. But they aren’t my photos, they’re old, even familiar photos that you could find anywhere.

TMN:What appeals to you about motion stopped in place? Is it the tension of something unresolved? Is there anything about it that you find repellant?

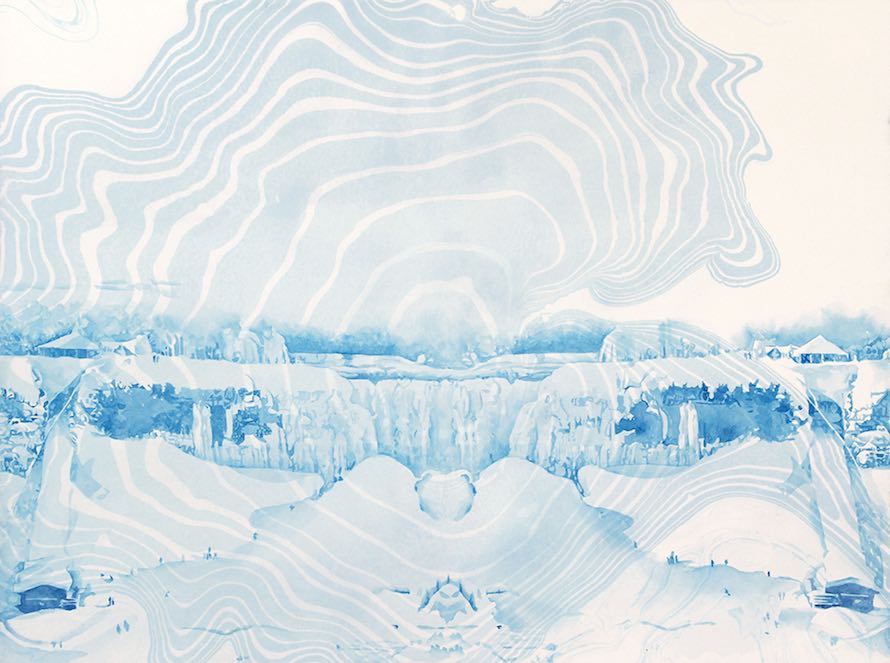

RB:The thing I find endlessly compelling about painting is that it’s a method of stopping time, or encoding it in material. An image of violent motion frozen makes that explicit.

Something else about violent motion is that it has an inevitable outcome. An image of a waterfall frozen, for example, is like retaining one powerful memory from a chain of events, and also like a kind of wish-fulfillment, keeping something still and under control that is unstoppable.

TMN:Does your artistic self ever freeze?

RB:Do you mean as in a “block?”

TMN:Sure.

RB:I seldom stop painting for more that a day or two. Sometimes I may not know if things are going in the right direction, flowing right, but I try to keep going and I push through those times.

TMN:Do you look back and see yourself working through different periods? Do you prefer some to others?

RB:There are ideas that I will become really captivated by for a period of time and work with intensively, that will seem to form pretty naturally into series. There are also images that recur from time to time, that are part of my vocabulary and have a developing symbolic meaning for me; maybe I won’t know what to do with them for a while, or what they’re about. Often what’s happening in the work is very connected to what’s happening in my life, almost the same thing.

There is work I’ve made that I’m proud of, but I’m always thinking about making something better in the future. I think of my life as a whole going toward something that I haven’t accomplished yet or may never accomplish. Sometimes it’s really good to look back on early work and feel affection for it, but know you’ve grown or see something to build on.

Looking back—a lot of the struggle of being an artist is creating a life that allows you do what you are compelled to do. The least successful times are when circumstance prevented bringing something to fruition. The last few years have been some of the most exciting in my life because I’ve been able to have a studio and work there every day. I stay immersed in what I’m doing for days at a time, and it feel like it moves very quickly.

TMN:When are you afraid?

RB:The most afraid I’ve ever been has been thinking someone was dying; thinking you’re dying yourself is probably a close second.

There are irrational fears, like being afraid of the dark or the supernatural, and rational fears, like being afraid of the ocean, something that simply big and powerful and indifferent to you. And that fear also has an aspect of awe and beauty. I love swimming in the ocean but I’m certainly afraid of it.

I’m also interested in the fear that one perhaps should feel but doesn’t—fear of climate disaster from global warming, for instance, which I don’t experience as a visceral fear. Something else about these frozen images of violent motion is, they are a distanced image of fear, very detached and intellectual. To me they are less about fear than thinking about how we think about fear, or safety.

TMN:Are you ever afraid in the art world, so to speak?

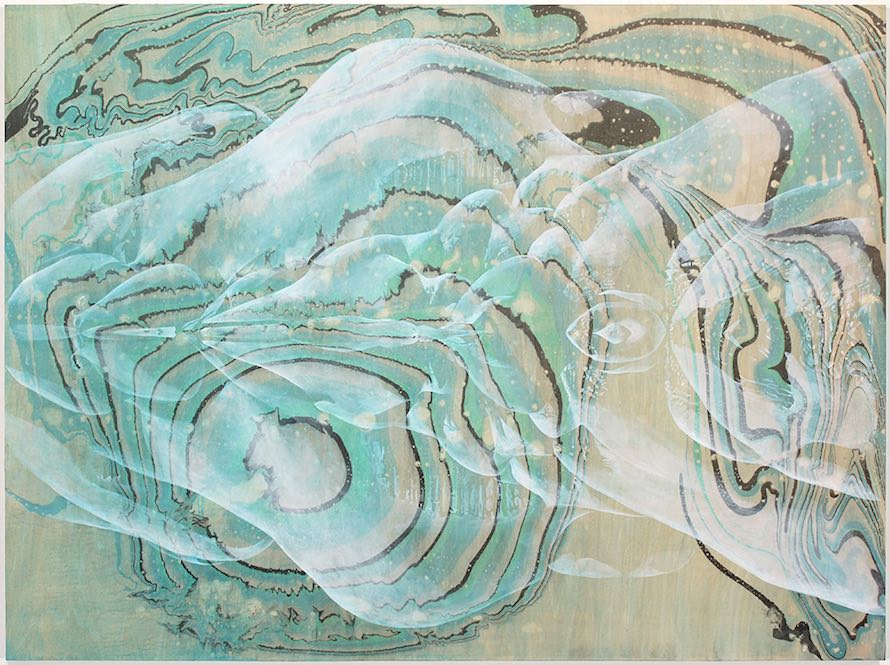

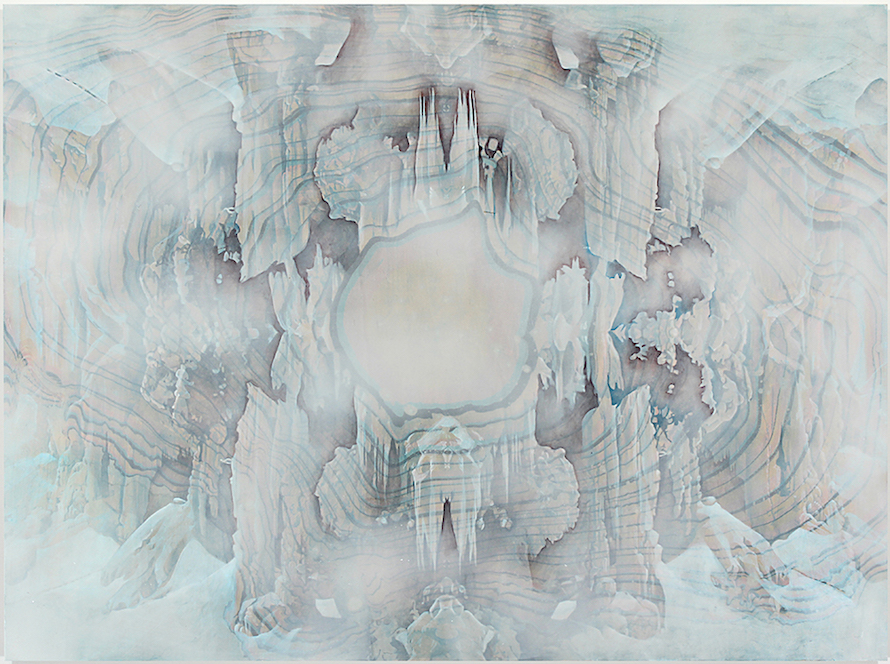

RB:Once I was at a museum reception and I became quite ill and passed out, ended up in a hospital. The art world is a rarified space, but biology and mortality intrude on whatever intellectual aims we’re pursuing. There’s an awareness that at some points you lose control—that’s an underlying current in my work. The imaginary landmasses I’ve painted, like islands surrounded by waterfalls, are constructing a place of safety. The implausibility of these spaces in the paintings reflects the fact that you can’t ever be totally safe.

The most frightening art experience I’ve ever had was Nathan Whipple performing as Triple Whipple at a small gallery in Brooklyn. It was two muck-smeared androgynes connected by an umbilical cord crawling screaming out of some kind of entrails, in a very small room. They were close to you and there was a palpable sense of defilement. I’m afraid I don’t know the name of his collaborator in that piece.

TMN:How much faith do you put in your unconscious as part of working?

RB:A lot. When I don’t know what I’m doing, when the imagery that’s developing surprises me, is always when it’s best. I think when you’re consciously directing yourself or making a statement, you’re usually not connecting to what is deepest or most interesting. It takes some faith to act while not knowing.

TMN:Does Niagara Falls have any romantic allure for you anymore?

RB:It’s funny you know—that kind of idea of romance seems pretty foreign to me now. I’ve been to some wonderful places, like Eiheiji Temple in Japan, or the Eiffel Tower is pretty romantic, but romance is such an old fashioned idea! I think I feel romantic about airports, just going somewhere, going away and coming home. New York was pretty romantic to me when I first came here, a kind of fairyland, and I still feel that way not infrequently.

TMN:Favorite airport then?

RB:Airports are romantic because they aren’t anyplace, they are between places, like the woods between the worlds. No “terroir” at all. The coldness and impersonality creates a sensation of being detached from your life, looking at it from the outside, but also a kind of eternal moment, like being your objective self in this non-place. The most efficient, clean, and indistinguishable airports, where you barely know where you are, are my favorites—like Zurich or Amsterdam Schiphol. But then there’s the Cairo Airport, where you stumble off a plane, find your bags, and a cab driver holds up a fake badge and tells you you’re under arrest to get you take his cab, which is the opposite experience; you know immediately that you’re in Egypt again.

TMN:We ask everyone, what was the first piece of art you ever sold?

RB:There was a broken-down old maroon brocade sofa with carved wood feet in the painting studio at Everett Community College in Everett, WA, when I was taking classes there as a teenager. Sometimes if I got to school early I would sleep there. Inevitably I’d wake up and find I was the model for a drawing class. The painting teacher was John Simpson, a great artist and friend. His joke was to have the morning class draw me until I woke up and ran off to whatever class I was late for… Anyway, at some point I made a little watercolor of that sofa, and it ran in the campus magazine, and someone asked me if I would sell it. The person who bought it was nice, he clearly liked it a lot, and I was a mix of surprised to get $75 for it, but also convinced that it was something good.

That place and time were important to me and I felt like you could see that in the picture. I got a sense of possibility from that exchange, a realization that I would find other people who appreciated the things I appreciated.