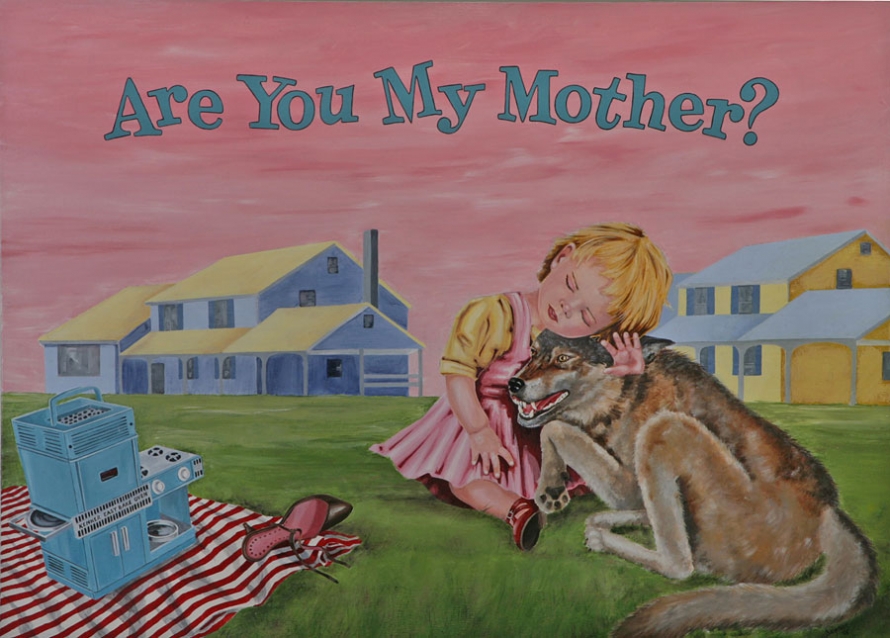

The ladies in Lauren Bergman’s paintings may leave a smear on your pristine mind, and that’s part of the point. The mythology of America, California in particular, is overrun with seductive women and coy little girls and so is Bergman’s Calhalla, currently on show at Corey Helford Gallery. But in Bergman’s world, the happy housewife would probably tie her husband to the back porch in his underwear before she’d greet him at the door with cocktail.

Bergman grew up in Washington, D.C. Select solo exhibitions in New York City include O.K. Harris Gallery and Makor Gallery. Group shows include Corey Helford Gallery in Los Angeles, Carl Hammer Gallery in Chicago, and Claire Oliver Fine Art in New York City. Bergman currently lives and works in Manhattan. Images courtesy Corey Helford Gallery, © copyright the artist, all rights reserved.

Based on the title and the architecture, we appear to be in some idealized California. Where are these paintings set?

In this group of paintings, while continuing an ongoing exploration of female identity, I’m placing the “idealized female” within the context of an idealized or “mythicized” America. Mythology has been a central theme throughout art history and in this show I’ve begun to posit, “What is our American mythology?” I’m using California as an archetype for the American idyll.

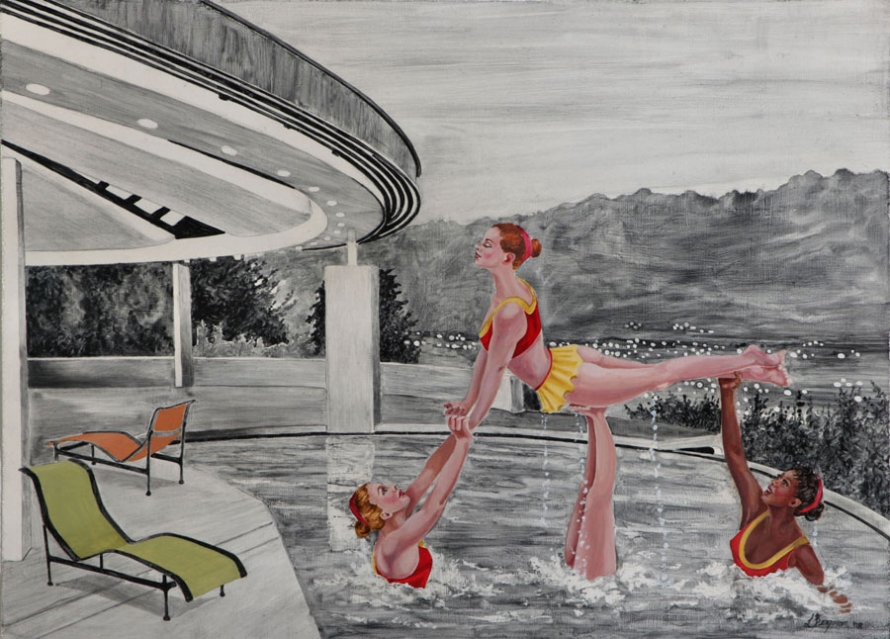

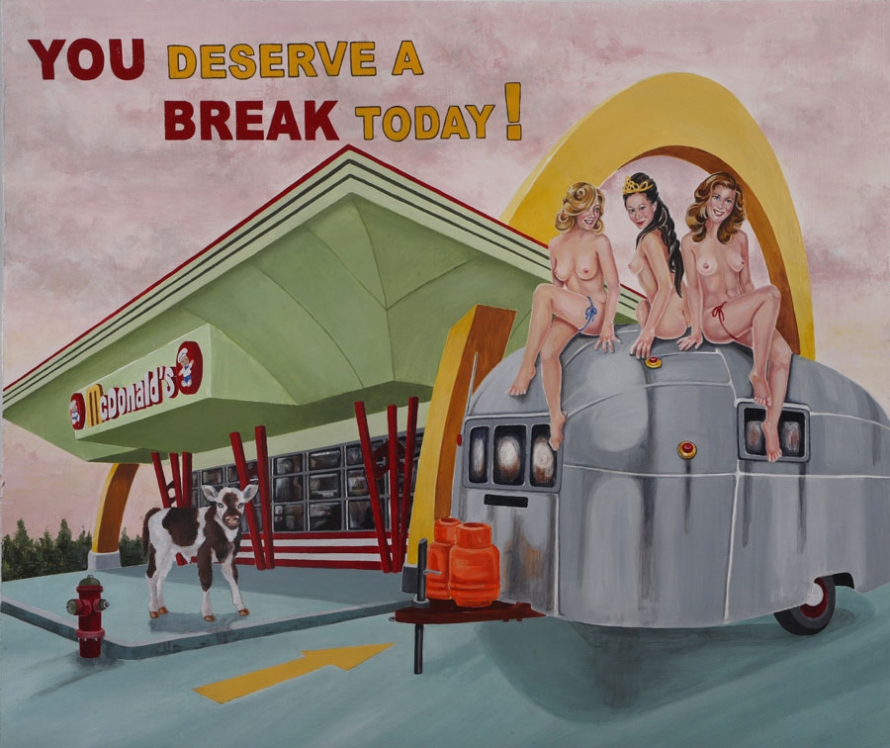

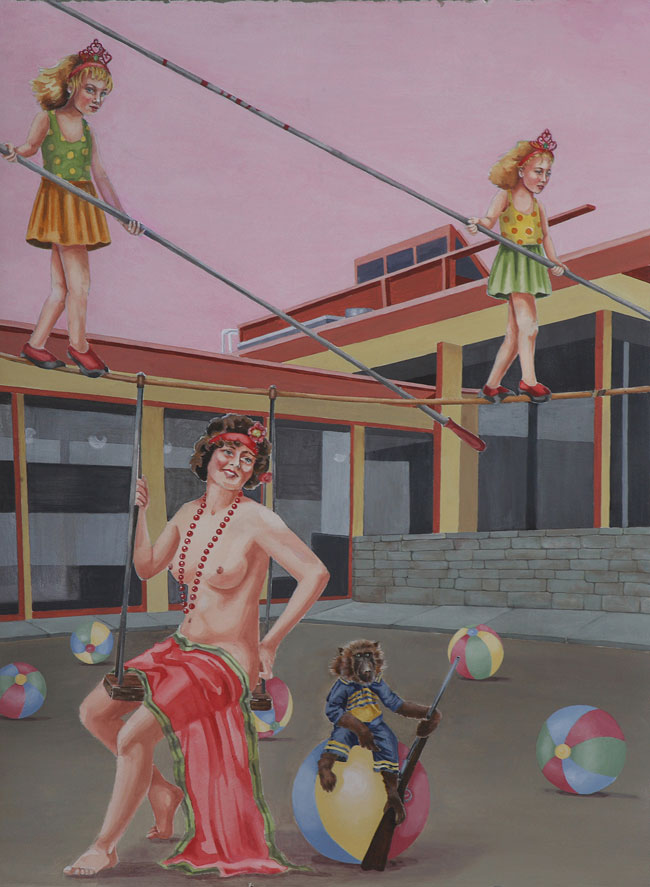

The show is titled “CalHalla: Dreams of Future Passed.” The title contrasts California and Valhalla alluding to how California and its mid-century architecture reflect the utopian idealization that exists in our collective unconscious: a sunny and modern Eden. Both the vast and sprawling tract-home neighborhoods (the “little boxes on the hillside”), populist in design, to the more daring modernist structures of Lautner, Neutra, Lloyd-Wright, and Koenig are emblematic of our collective future vision of hope and optimism. If America were to have a Mount Olympus it would look like these buildings and our goddesses would look like pinup girls residing in this modernist paradise.

It’s surprising that work with such a tie to advertising looks so American. Are the representations of mid-century advertising really that ingrained in our national identity?

Like the proverbial snake swallowing its own tail, a culture creates media, and media affects culture, and on and on until it’s unclear whether media is a product of our culture or culture is a product of the media. I reference mid-20th-century imagery partially because by distancing ourselves from its original context we view it as separate from contemporary culture, allowing for perspective. Yet even viewed through the lens of irony this time period and these images exist within our culture as our mythical version.

When I asked my editor if we could interview you for a gallery, his response to your paintings was, “ooh, sort of hot.” And I agree, the paintings, though they do strike me as commentary, are sort of hot. Was that your intention?

The central ongoing theme of my work is the exploration of female identity. How cultures have portrayed women historically is generally through goddess imagery, royalty, maidens dancing in the forest, etc. I have chosen to focus on the depiction of women in advertising imagery as a way of entering the dialogue. Commonly women are portrayed as either sexualized or infantilized (or both). The big-eyed pouting pin-up girl sold everything from cigars to cars. Contemporary advertising, while perhaps less coy, is little changed. So while I paint the idealized, sexualized female, by the very nature of the fact that I am a contemporary female the work by default becomes a somewhat politicized commentary on the barrage of images and messages that to one degree or another inform and define our identities. And gender politics aside, it’s just a lot of fun to create these hotties and place them in absurd contexts.

Especially in this series, the women you paint have a certain jovial, or joking power, like this is all tongue-in-cheek. Who are your subjects?

I often use classic pinups, vintage erotica, Bettie Page and Josephine Baker photographs as reference material. I seek out images both of women and the other elements of the paintings that have some sort of iconic resonance; images that illicit a collective emotional response.

The paintings contain a lot of childish accessories, even actual children, juxtaposed with “naughty”-seeming text and half-dressed women. Is this a comment on infantilization of women in art and representation, or is it more complicated than that?

I like the juxtaposition of the idealized little girl next to the idealized woman and the resulting tension between the infantalization and the overtly sexual. It pokes at the grand dilemmas of “naughty vs. nice”, “good vs. bad”, or “angel vs. devil.” Yet while the little girls appear innocent and naïve, on closer inspection they are quite fearless.

How do you come up with a concept for a painting?

I was excited about having my first West Coast show and started thinking about the paintings in a California context. Having lived on the East Coast my entire life, California has always existed in my mind as the utopian America. Mid-century California imagery seems to epitomize how we collectively envision that better, brighter future. Once I have the concept I pretty much see groups of finished paintings in my head. The time-consuming part is actually making them. Any text used is taken directly from actual advertisements or printed material. I have piles of vintage magazines and extensive digital files that I’ll pour through until I find text that works. In addition to using source material for the figures I also have a group of lovely girlfriends who generously let me use them in my paintings.