TMN: What’s your background in art? Have you always been an artist?

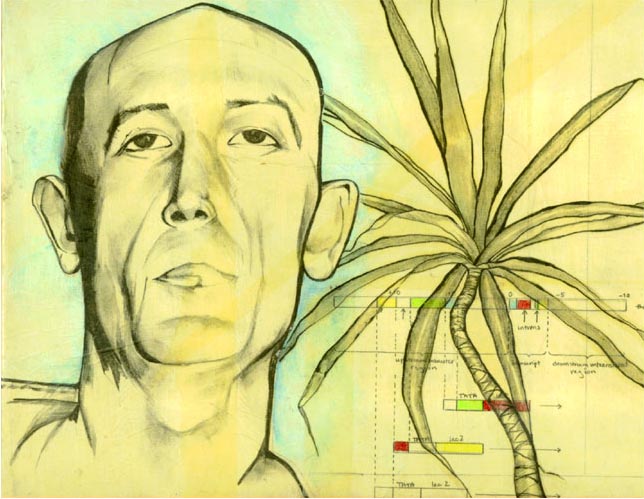

CO: I have not always been an artist. My father is a physician, along with what seems to be everyone else on that side of the family, plus I have an enormous fascination with anatomy and the body. So, I always thought I was going to be a doctor. I began college as a pre-med student, but found myself stifled by the pre-determined plan of it all. Change and serendipity became the running theme in my life as I fell in love, made a trans-continental move to Los Angeles, and swapped my major for creative writing.

Writing was the instigation to art and the creative process for me. (I mentioned that my father’s side of the family is all doctors, but it seems that his overwhelming rationalization and pragmatism were balanced by my mother’s creativity and whim—her family is all artists.) I always knew I could draw and paint, but I had never put any focus into it until my drawing teacher encouraged me to relate my drawings to my stories. It wasn’t until the last year of college that I decided to minor in Fine Art. And ever since then my writing and my art have been very closely linked. Back then I was writing these deeply sad and surreal stories, but in every broken story there were shards of bizarre beauty. And I think this idea became a foundation for all of my work.

TMN: What, in your words, are the ‘diagrammatics’? What’s behind the name, and what inspires them? Can you describe the process by which you fit the objects together, both in your mind and on paper?

CO: The word ‘diagrammatic’ is an adjective describing ‘a drawing, sketch, plan, or chart that makes something easier to understand.’ I simply fabricated the noun ‘diagrammatic’ from the adjective, because, well, I think a fabricated word is very fitting to describe this series. And it lends itself to the humor behind the pieces as well. In college, I was into dramatic nudes done with dark lines of charcoal. It was much more expressionistic. But now, my work is lighter and tighter, and humor has become a subtle aspect of my work. The diagrammatics hold substance, yet it seems to be derived from nonsense—kind of how I perceive Los Angeles. But that perception definitely relies on a sense of humor.

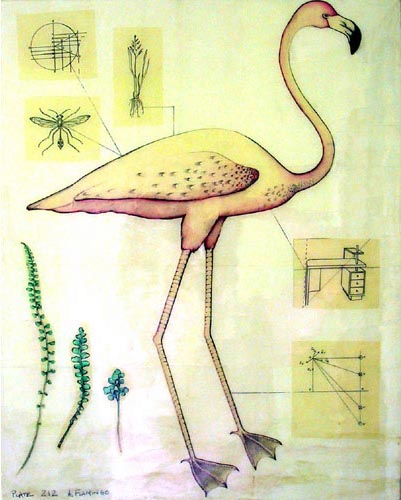

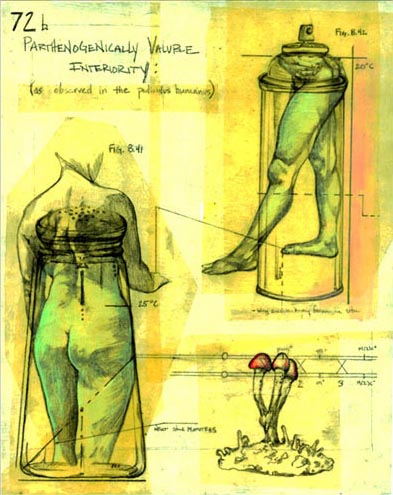

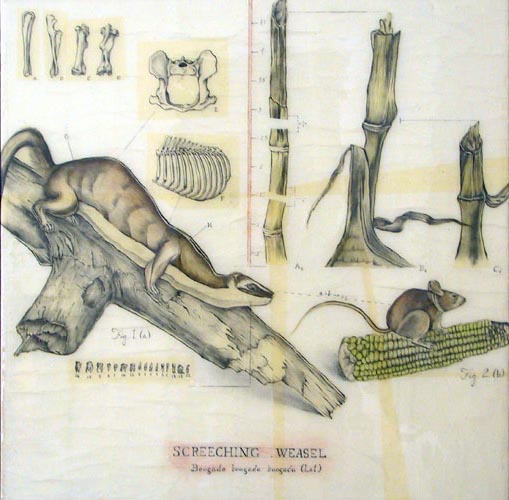

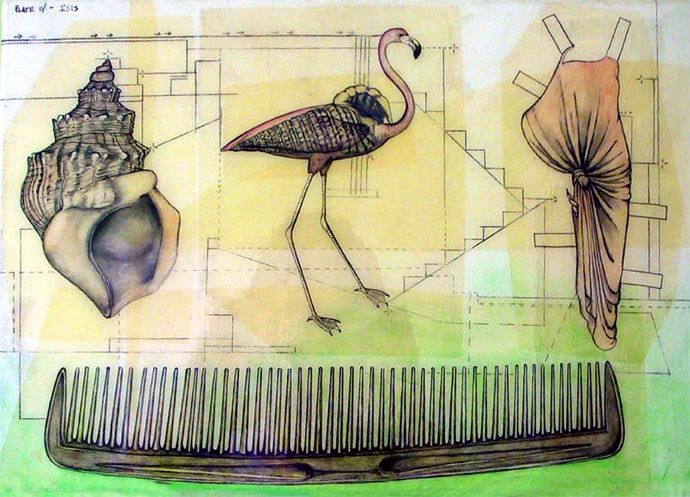

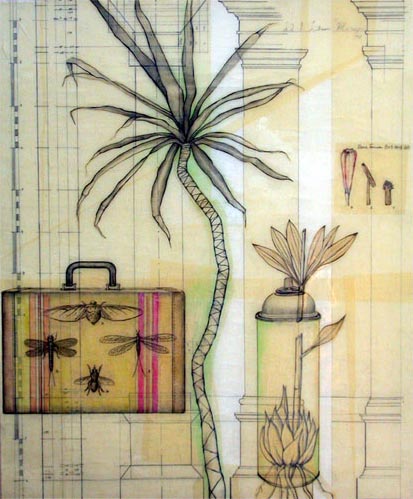

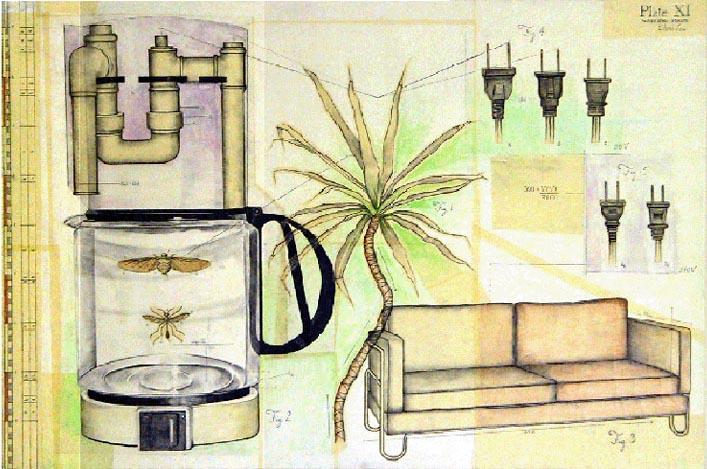

Diagrammatics is a series that exploits the illustrative print style of earlier centuries with detailed, technical lines and a sterile disposition. However, as the word suggests, a diagrammatic consists of a language, a dialogue between objects. And as a result, I believe a story is told within each piece. And as common objects are placed within new contexts, they are oftentimes given new meaning.

The process behind the pieces is actually a collage, but I don’t like calling it that because the word ‘collage’ is misleading. I do the drawings with graphite on separate pieces of vellum, and then I work with these pieces to create a larger image. After I fit all the pieces together on the canvas, and add a bit of color, I cover the canvas with a thick layer of resin. Unfortunately, the effect of the resin goes unseen in pictures. But it creates this fantastic sheen, giving the pieces an ephemeral effect—as if they are just fabricated, transient dreams, or perhaps a bizarre bug that has been pinned behind glass, and therefore made eternal.

I usually have an idea in my mind of what I want to create, but usually the final product is so far from the original plan. I’m not sure what my thought processes are behind my work, but I am fascinated by them nevertheless. I am fascinated that I can begin with a simple attraction to a single object—an attraction that stems from shape, lines, or even social relation—and then after combining several of those single attractions, or objects, the final product results in an amalgam of so many different parts of me. It is usually after I have finished a piece, when I am able to sit down in front of it, that I can really work it out. It is then that I begin to understand where the specific attractions come from, or why I combined them the way I did. And sometimes, it is not until a stranger approaches me and wants to discuss the relationship between an asparagus and a water pipe that I finally recognize a place in me from which that idea came.

TMN: Are there any diagrammatics that you haven’t yet created? Are you still making them? Can you see them in anything you look at, in the real world?

CO: There are so many diagrammatics that have yet to be created, and yes, I see them all the time, in both my imagination and in real life. I mentioned that I have a fascination with anatomy and the body, and I feel like I’m about to dive head-first into the pit of all that good stuff. I have watched my dad do open-heart surgery numerous times, and each time I remember thinking how sadly foreign our own bodies are to us. Organs and guts and bones connote disgust and death, but yet they are utterly vital to life. Just a few inches beneath our chests lies our heart, an organ we will never see, yet upon which we rely for life. For me, that is surreal. Life is fleeting, and just like the bizzare bug, it needs to be captured, documented, and put behind glass.

TMN: What inspires you, as an artist? Music, film—everything? How would you describe your style?

CO: Wow, I’m inspired by so many things. Everything from the cracks in the sidewalk to the sound of spinach being squashed down into a porcelain bowl. But some of the obvious inspirations would be illustrations (textbook or print), and the intricacies and design of gadgets and machines. And I must not forget Los Angeles. I have lived in L.A. for four and a half years now, and it has taken me three of those years to be able to say I love it, and mean it. There is really no other place like L.A. I can stand on the beach in Venice, on the edge of the continent, looking out towards the ocean, with mountains on my right, airplanes flying no more than ten thousand feet above me, and I’m surrounded by people who are making a career out of detecting metal. It’s fantasy made reality. And in this I find beauty, as I find beauty in plants growing out of aerosol cans and women being bottled in salt shakers. I want to ground wonderland through clinical diagrams. I want to document the imagination, or maybe just a single dream.

As many authors have more eloquently stated: Los Angeles is the symbol of the American dream, yet that’s all it is, a mere, intangible symbol. L.A. is just the last stop on the westward search for the ‘good life.’

My boyfriend is an actor, and although I miss some of the twenty-some-odd films he watches each week, I probably end the week with five or six new movies in my cine-file. So I think I would be crazy to say that I am not influenced by film. Hal Ashby is one of my favorite directors—I am attracted to his slightly skewed and exaggerated version of reality. In this I find a likeness to my own work.

One of my favorite movies is She’s So Lovely by Nick Cassavetes. She’s So Lovely is not a remake, but more of an homage to his father’s (John Cassavetes) film A Woman Under the Influence. Both films are amazing stories about a woman and man who maintain this absolutely beautiful and pure love amidst insanity and chaos. It’s that whole serendipity thing again.

Gallery

Diagrammatics

Read artist interview