How did you come to choose these three areas—the US, Japan, and western Europe?

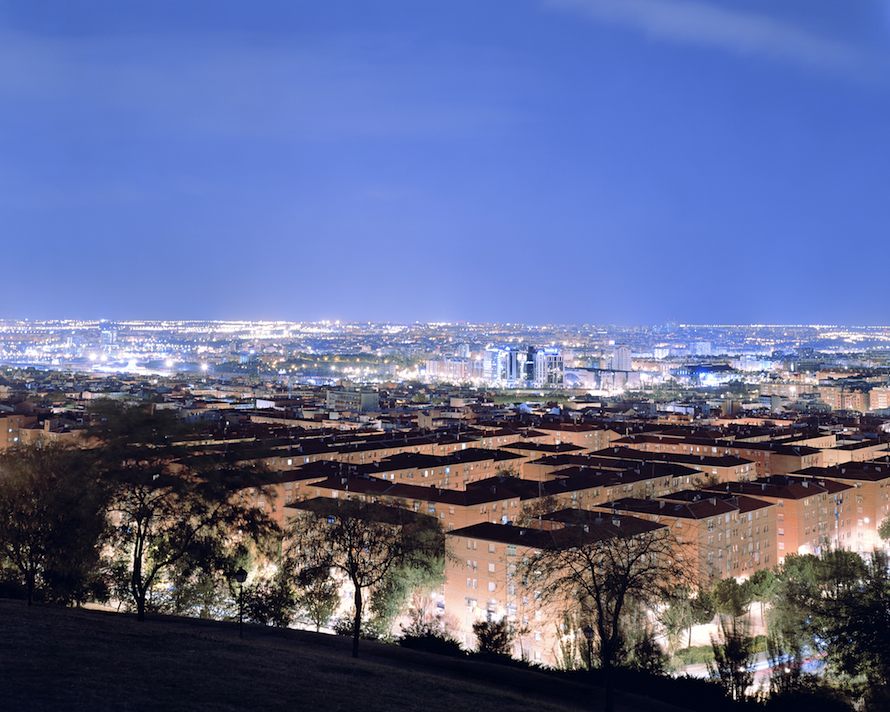

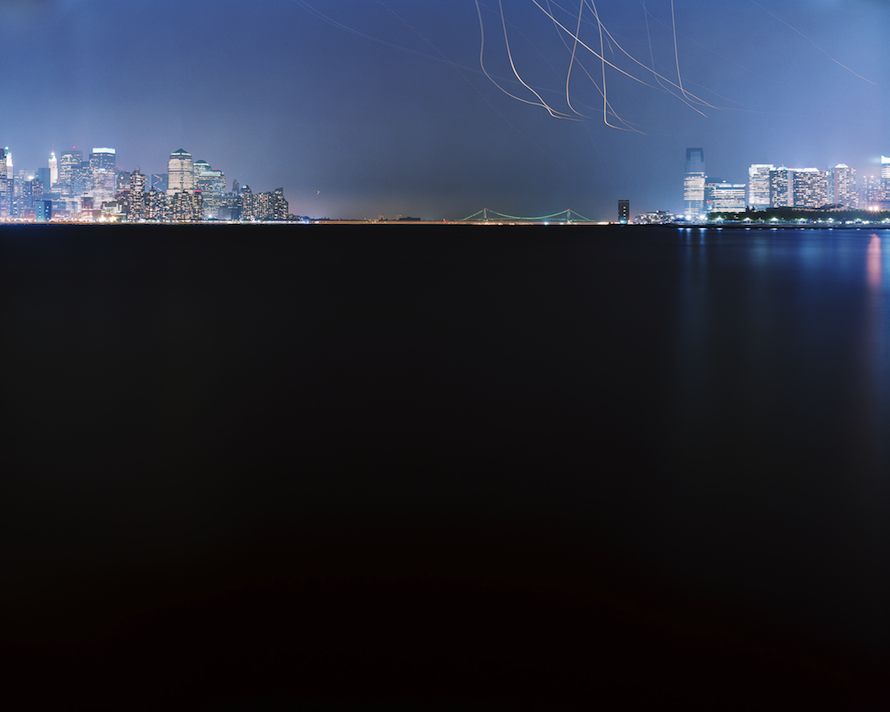

Christina Seely:“Lux” is made up of photographic portraits of cities within the most brightly illuminated regions on the NASA map of the earth at night. About five years ago I rediscovered this NASA map and I became interested in the dialogue between the beauty produced by manmade light and the complexity of what this light represents.

The distribution of light, with three regions noticeably brighter than the rest, read as a form of information about human activity and our relationship to the planet. The US, Western Europe, and Japan (with China now coming close in as a fourth), are not surprisingly the wealthiest, most powerful, and most consumptive regions in the world. Together they use around two-thirds of the world’s resources and create about half the world’s CO2. While these statistics lead to the obvious conclusion that this light represents an intensely negative impact on the planet, since its inception manmade light has also represented a range of fundamentally positive and hopeful things—ingenuity and progress, innovation and growth, prosperity, amusement, optimism and promise. My real interest lies in this contradiction and what it reflects about our current relationship with the planet.

TMN:Artificial light isn’t often construed as beautiful. Are there urban-light aesthetics we’re overlooking?

CS:Over the last few year the public conversation about light as pollution has increased exponentially. There has been a mass call to tone down its overall use, which many cities across the world are working toward. More often than not, urban light is unnecessary and often unappealing. At the same time electric light is used to enhance the identity of cities. It’s used to outline the Eiffel Tower in Paris, or the bridges in the San Francisco Bay Area, or to accentuate the changing maple leaves in Kyoto in the fall. When it’s thought of as beautiful, we are looking at it and considering the city as place. When it’s thought of as pollution, we are looking beyond it and considering what it it might be blocking out, what we are no longer connecting to—natural night, natural rhythms.

TMN:Have other light-focused artists influenced your work?

CS:Many artists I draw inspiration from make work that deal in innovative ways with our perception of light and time. For example, the experiential works of James Turrell and Olafur Eliasson. I am also a particular fan of Hiroshi Sugimoto’s theatre series. In each photographed theatre, the length of the photograph’s exposure is equal to the length of the film playing on the movie screen. The light from the screens build to bright white, creating compounded and stilled information. The capturing of an entire story and the reference to the passage of time are indicated in such an elegant way in this work.

The exposure times for “Lux” are between one to four hours long, so trails from airplanes and cars, the smoothing of the water’s edge as the tide comes in, the moon rising, and even stars tracking across the sky—all offer traces of the passage of time and refer back to the medium being used in ways that draw on Sugimoto’s series.

TMN:You’re currently shooting in the Arctic on a very different project. Have your ideas about light changed as you’ve lived and worked so far away from cities?

CS:Definitely. The new project, “Markers of Time,” was inspired by a three-week trip on the Bering Sea a few summers back where I witnessed 20 hours of daily sunlight during the height of summer wildlife migration. The intense contrast between photographing cities at night for Lux over the previous five years and this trip on the Bering Sea led me to think about our various attempts to control time and how this tendency dangerously eradicates our relationship to the planet’s inherent natural rhythms and cycles.

So last year I moved up to Alaska for six months between summer and winter solstice in order to witness and understand what going from 20 hours of light to 20 hours of dark would do to my body from a biological standpoint and to have a period of time where I was supposed to be paying close attention to natural rhythms. There is no doubt my ideas about light have been effected quite a bit. My experiences have only emphasized how very much out of sync we are in modern city life with natural rhythms. I have gained a new and more complex appreciation for both day and night.