Who are the sleepers?

Dhruv Malhotra:The sleeping human figure, in the context of the larger urban landscape surrounding it, is the metaphor I use to address my own self and the world around me. Usually intentionally obscured, the sleepers are the people in my images who choose to sleep outdoors, for a variety of reasons, and are often guards, migrants, and construction workers, amongst others. The specific person doesn’t much concern me, as my intention is to use the human figure as a metaphor and a point to explore my concerns about the urban landscape.

TMN:If sleepers awaken while you’re photographing, how do you react?

DM:Usually I just speak to them. Some are a bit surprised at being photographed sleeping, but most go right back to sleep after minimal persuasion, once their sense of threat and alarm is allayed.

Many of these moments of awakening have translated onto film as ghostly shapes emerging from sleeping bodies—moments of awakening glimpsed along with the dormant potential of the sleeper.

TMN:When not taking photographs, what else do you do at night?

DM:Often I just look at photographs or read about them. Usually I read a lot, think, hang out with friends, drive. Sometimes I sleep.

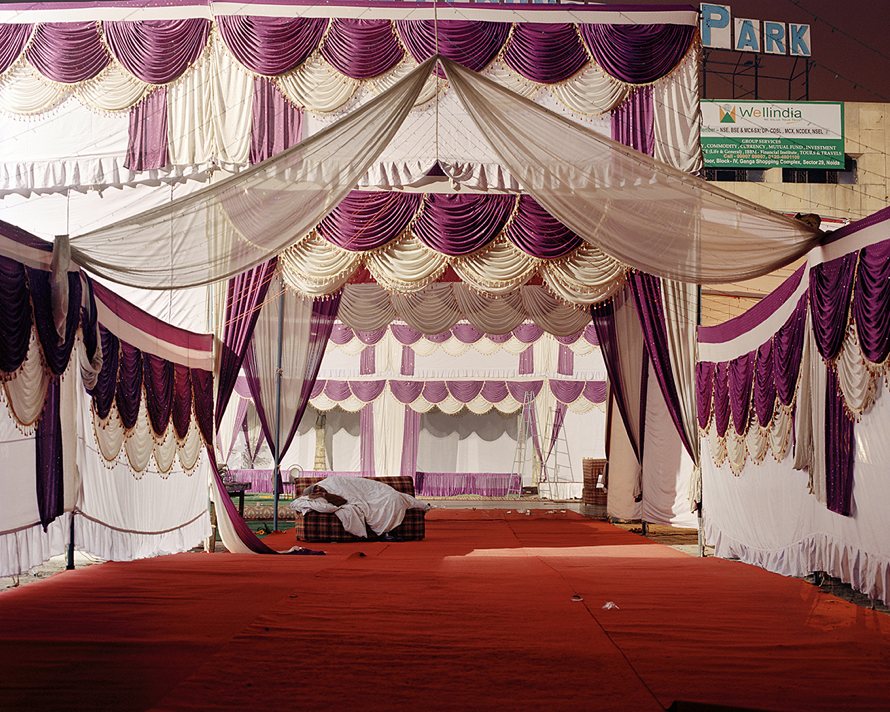

TMN:Your photos capture scenes that are desolate and silent, instead of the noisy chorus of auto-wallahs and honking buses we usually associate with city life. What do they teach us about nighttime in urban India?

DM:The noise and the honking don’t usually prevail at night. The night is a silent, eerie, and almost otherworldly kind of space, one that is largely deserted and absent of the crowds of people who are around by day. That is one of the reasons I prefer working at night, and part of my intention is to look at these silent places that lie at the edge of a borderland of sorts and to disclose what the darkness holds, in order to find a sense of sentience.

TMN:Describe the art community in Jaipur. How does it compare to Delhi?

DM:Usually I’m in Jaipur visiting my family or living on a farm outside the city, so I don’t know much about the art community. But it is probably more nascent compared to Delhi, as it is a much smaller city.

TMN:What are you working on now?

DM:A couple of projects that “Noida” and “Sleepers” have led me to; playing around with the idea of a book at some point; and some new work. I wouldn’t want to say much and gaffe—I’d rather just wait and show you!