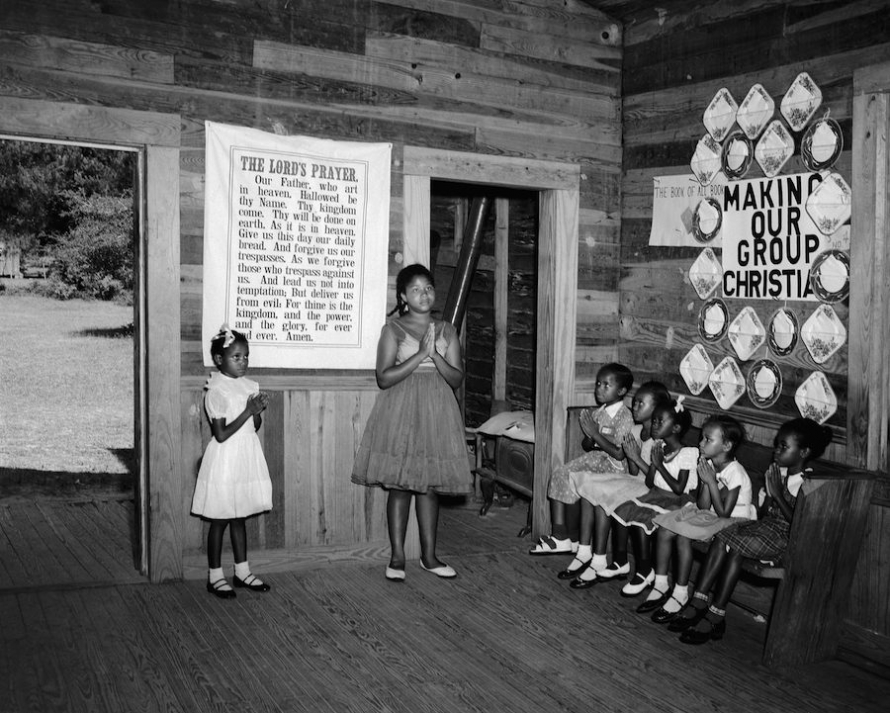

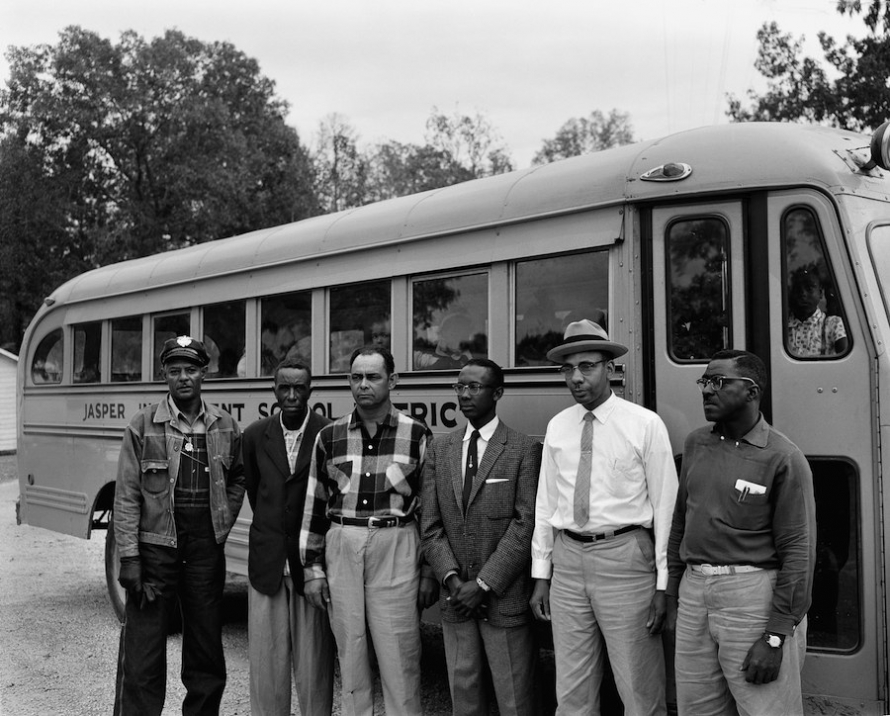

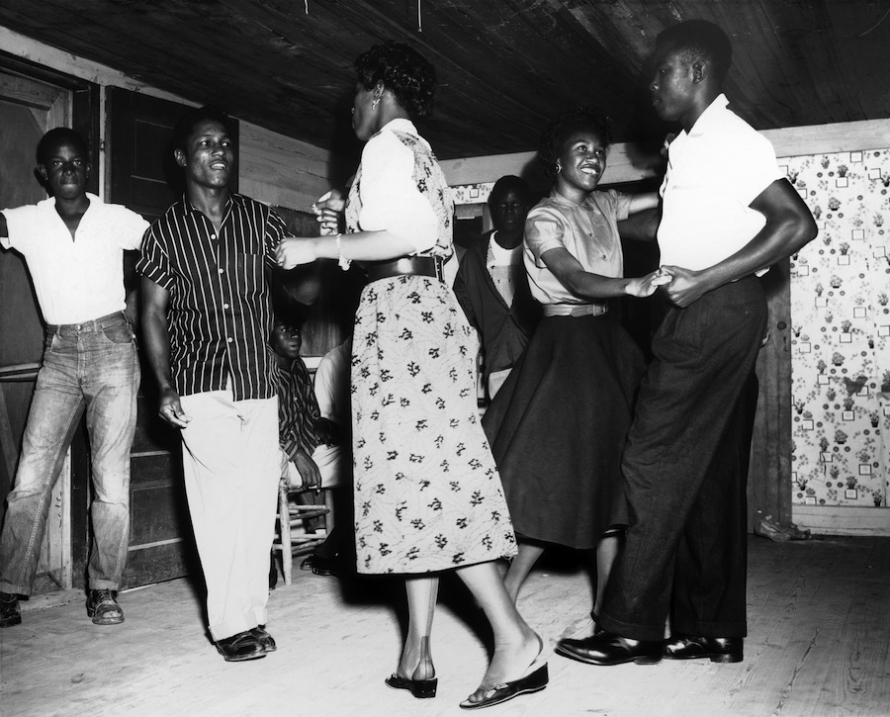

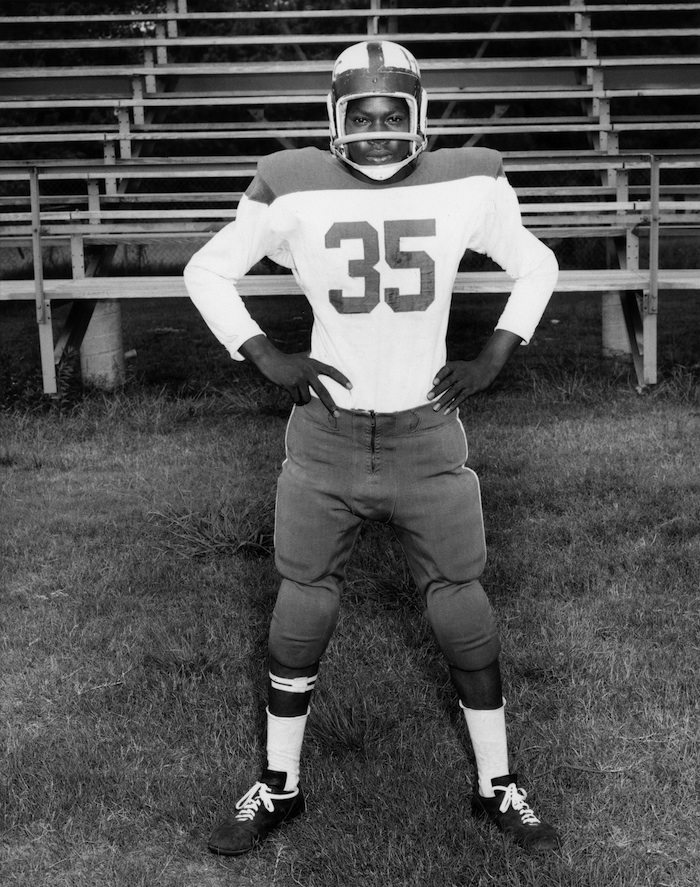

You might recognize Jasper, Texas, as the scene of the 1998 murder of James Byrd, Jr., which brought the East Texas town into headlines. But the complex social life of Jasper’s historically segregated citizens goes beyond the killing, as we see in Alonzo Jordan’s photos of the town, taken from the Great Depression to the Civil Rights movement and beyond. The photographs show a fascinating view of segregation, and highlight the value of community photographers as recorders of history.

Curator Alan Govenar is an author, folklorist, photographer, and founder of Documentary Arts, Inc., a nonprofit organization that presents new perspectives on historical issues and diverse cultures. Govenar is the recipient of a 2010 Guggenheim Fellowship for his work on African American photographers in Texas and is the cofounder with Kaleta Doolin of the Texas African American Photography Archive in Dallas. Jasper, Texas: The Community Photographs of Alonzo Jordan is on view at the International Center of Photography through May 8, 2011.

How did you decide to feature these photos in an exhibition?

I first learned about Alonzo Jordan in 1995 from Lloyd Thompson, a history professor at Wiley College in Marshall, Texas, whose wife had grown up in Jasper and was an elementary school teacher in the town. Alonzo Jordan had made her school photographs. At the time, I was completing my book Portraits of Community and was administering an internship program for Wiley College students at the Texas African American Photography (T.A.A.P.) Archive in Dallas that I had cofounded with Kaleta Doolin earlier that year.

On June 19, 1996, I drove to Jasper and met with Alonzo Jordan’s widow Helen Jordan. After a lengthy discussion, Mrs. Jordan decided to donate more than 6,000 prints and negatives to the T.A.A.P. Archive because she wanted to preserve the collection and help her husband to receive the recognition that he deserved. Mr. Jordan’s studio had been damaged in a storm and the collection was in desperate need of conservation.

This exhibition marks the first major presentation of Alonzo Jordan’s work, which spans the period from 1943 until his death in 1984.

What was segregation’s effect on the black community of Jasper? How did these photos reflect or affect that?

Racial separation was a way of life in Jasper. “We were totally against segregation,” Helen Jordan said, “It was a horrible thing, but on a day-to-day basis we were working hard to make our business and our church and schools what they are supposed to be.”

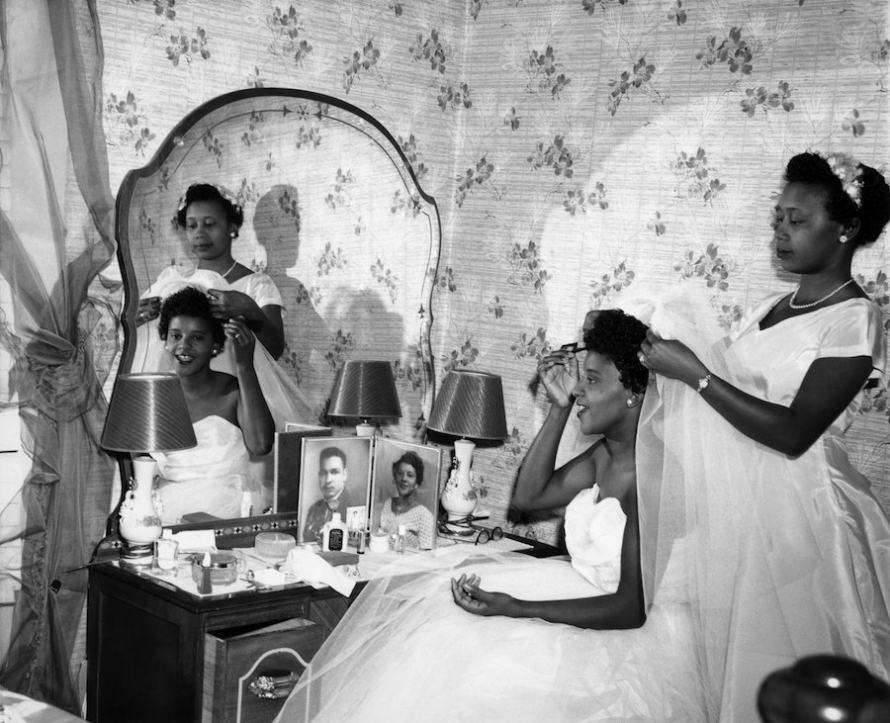

Alonzo Jordan’s photography was mainly service and commercially oriented, but it was also highly personalized, and in this way offers a unique window into the social and cultural milieu of Jasper and the surrounding communities in which he worked. Today, Jordan’s photographs can be found all over southeast Texas, not only in public places, such as the offices and hallways of churches, schools, libraries, and community centers, but also in local businesses, as well as in family albums, yearbooks, brochures, and an array of commemorative publications.

When did Alonzo Jordon decide to start photographing the life of Jasper?

A barber by trade, Jordan was also a Prince Hall Mason, a deacon in his church, an educator, and a local leader, who took up photography in 1943 to fill a social need he recognized. Over the years, he chronicled the everyday world of black East Texas, especially civic events and social rituals that were integral to the daily life of the people he served.

Was this kind of photography of a town’s life common in that era?

Like many small-town photographers, Alonzo Jordan fulfilled various roles in his community. Across the nation photographs of this kind have been proudly displayed for decades in people’s homes, local churches, businesses, civic buildings, and schools because they document groups and individuals who are held in high esteem. Frequently, the photographer is not identified or credited because the emphasis is upon the family, social and professional groups, and the recognition of the community infrastructure.

Are these photographs art or journalism? Is Jordan an artist?

“Jasper, Texas” challenges existing formalistic approaches to the study of vernacular photography and considers Jordan’s distinguished career as a “community photographer,” who actively documented the world in which he lived and worked. Jordan’s photographs have become part of the larger public memory of Jasper. The aesthetics of these images is secondary to their content. At a time when racism and discrimination undermined the fundamental rights and aspirations of African Americans, Jordan countered the degrading images that were insidious in advertising, newspapers, and magazines. The photographs presented here are an expression of history and pride, testaments not only to experiences shared and talked about, but to beliefs and values that are at the core of local cultural traditions during the Civil Rights era.

How do you reconcile the pleasant life we see depicted in these photos with the reality of “separate but equal”—as well as with the 1998 murder of James Byrd, Jr.?

How we perceive and understand the photography of Alonzo Jordan, more than 25 years after his death, is inevitably affected by the magnitude of the James Byrd hate crime that traumatized the African American community in Jasper. While Jordan’s photographs offer a distinct counterpoint to the media coverage that inundated Jasper during the period between the murder and the last trial, they nonetheless raise difficult questions about how one views photographic images retrospectively.

In looking at Jordan’s photographs, we want to search for answers or clues about the underlying racial tensions in Jasper, but there may be none. Perhaps the absence of photographic evidence, given the history of racial violence in the region, is in its own way revealing. The photograph in this context has a different purpose. Jordan’s photographs were an affirmation of the fundamental traditions, values, and beliefs of the community in which they were made. As Jasper resident Oletha Woods explained, “Segregationally speaking, it was kind of bitter in Jasper, but how you responded is what made the difference. You can make things better or you can make things worse, and I try to think positive about everything. Mr. Jordan wanted to help make things better.”