Looking at the City or, the Look From the City

by Takuma Nakahira

It can no longer be recovered. Whenever I am presented with the photographs of Eugène Atget I am overcome with this feeling. For a very long time I have tried to figure out exactly where it comes from. This is also the main reason why I am attracted to Atget. Yet, now that I am compelled to write about Atget once more, it would be no use to merely describe these vague sorts of impressions.

Eugène Atget, who in the midst of destitution ceaselessly took photographs of the streets of fin-de-siècle Paris, eking out a living by selling these as “documents for artists,” died alone in obscurity and poverty, an artisan of photography. Furthermore, there is Atget who after his death became a tremendous influence on the surrealist movement. This has even become a kind of myth. These humanistic aspects of Atget have been described by many people starting with Bernice Abbot and will be a story handed down for generations hereafter. But with my extremely personal feelings of attraction to Atget as my only lead, I will instead think about Eugène Atget, and moreover, what photography exactly is.

This “irrecoverable sensation” I feel when looking at Atget’s photographs may certainly emanate from the spatial and temporal gulf between fin-de-siècle Paris and myself in the present. But if it was merely this, then we know of many photographs besides Atget’s that have this kind of nostalgia, or those that entice our yearning for far off places. The sole value of these prevalent banal photographs is derived by transporting ever older, ever more distant things through the photograph to us in the present.

Unlike these, Atget’s photographs each go beyond this enormous gulf of space and time, and while I am entangled with the remote memories of the experience of having encountered and seen this scene somewhere during my not-so-short life, I am brutally confronted with the “irrecoverable” thought of having never been to this scene, this street captured by Atget. Or in other words, Atget’s is a kind of photography where in the end, I am thoroughly ejected from these streets, these material objects. What I described by saying, “it can no longer be recovered” comes from the connotation of this sensation of rejection. Surely I have seen this sort of sculpture in a park somewhere, seen a sculpture and trees reflected in the surface of a pond in the same way, surely I have felt the midsummer rays of sunlight pour upon me, filtering through the trees just like this. I have a childhood memory of drifting through a place just like these antiquated streets, passing along a surface just like these stain-saturated walls. But no matter what, these branch filtered rays of sunlight, these streets of Atget are absolutely not my own.

In the end, the images of Atget reject my own memories and feelings; the streets indifferently stare back at me as streets and the material objects stare back as objects. In these images my attempts to ascribe significance or sentimentalize cannot penetrate into them. They entwine themselves within my memories, and yet ultimately they reject these completely with a kind of twisting. Atget’s photographs hang suspended in midair between this kind of attraction-catharsis and repulsion-alienation. This is where the unique characteristic of Atget’s photography lies.

Be that as it may, there are no human figures in Atget’s photographs. As Walter Benjamin aptly pointed out, they are like “scenes of a crime.” Even when people appear in them, they are stripped of personality, and most have somehow been completely embedded within the city or within material objects themselves. The streets, the people and the material objects are dead silent, as entirely identical elements, each stripped of their individual shadows. They are completely disillusioning, like when one peeks through pale florescent light into the world beyond the glass of the fish tanks lined up in an aquarium. This is what instills terror in their viewer.

However, what is seeing exactly? I understand the fact that seeing is to possess and give meaning to the world according to the process of establishing a secured distance between myself and the subject, reducing the world to a subject which must be something visible. But what happens if this distance disintegrates? All this will be a bit personal, but a few years ago I was hospitalized for close to a month with a condition of a constant sensory abnormality that was brought about as a result of my habitual use of sleeping pills, which I had been taking for insomnia. It is difficult to briefly describe the hallucinations I had at the time. I call them hallucinations, yet it was not that I was having visions of something that was not there. This condition was instead the disintegration of this sense of distance, the loss of the balance that maintains the relationships between material reality and myself.

For example, if I was at a café talking with a friend, I would suddenly notice that there was a glass on the table. In that instant, I could not ascertain the distance between the glass and myself. As a result, I was unable to recognize the glass as a glass. Once seized by the attack, I became seemingly immobilized with terror, and although at the time I completely lost the composure to be able to analyze indifferently what was happening, later I would look back and realize that this was exactly what was happening.

Looking out at the scenery beyond a train window, suddenly material reality would come at me and directly pierce my eyes. In order to protect myself within the train car speeding on, (the anxiety that I was unable to control myself and would leap out the window was very strong), I had to close my eyes and tightly clutch the armrest. Under this kind of sensory abnormality, I firmly believed that consciousness was a mass of scar tissue from the wounds inflicted by material things directly upon my eyes or my retina. For seeing material things meant that they would directly stab into my eyes. No longer able to go out and walk the streets, I was thus hospitalized. It’s not as though this anxiety has been eliminated, for even now my consciousness is taken over by that of a sick person’s. Therefore, isn’t “seeing” exactly the act described by the reversed expression, “material reality would come at me stabbing?” While looking at Agtet’s photobook, Paris du Temps Perdu I suddenly recalled all of this.

I’ve written the phrase “Eugène Atget’s photography” nonchalantly before. But it would be more appropriate to say “the worlds that occasionally entered the camera operated by a professional artisan of photography named Eugène Atget.” That is to say, Atget did not take photographs according to a pre-determined image that Atget himself had. He turned the camera towards all objects and all the streets of Paris. These were without fail then fused upon dry plates in accordance with the laws of optics. We cannot ignore the conditions of the development of film and the camera at the time, of the era, that shaped the characteristics of his photography. He had to take long exposures with low sensitivity film, which completely removed people’s forms. This also made it impossible to take photographs at night. Thus, these photographs that resemble “scenes of a crime,” were in no way the realization, the representation of pre-determined images he had in mind. They became that way out of necessity. It is an undeniable fact that the level of technological advancement in photography of that era decided the nature of Atget’s photographic images. In this sense too, his photographs were not photographs that had been permeated by his own consciousness. Instead, it was the elements that Atget was not conscious of, the elements of the unconscious, which decided the nature of his photographs. The fact that we are moved when we see his photographs is precisely because the world ruled by this “unconscious” conveyed through Atget’s camera stirs our consciousnesses even today. Walter Benjamin aptly grasps something like this in his “Little History of Photography.”

No matter how artful the photographer, no matter how carefully posed his subject, the beholder feels an irresistible urge to search such a picture for the tiny spark of contingency, of the here and now, with which reality has (so to speak) seared the subject, to find the inconspicuous spot where in the immediacy of that long-forgotten moment the future nests so eloquently that we, looking back, may rediscover it. For it is another nature which speaks to the camera rather than to the eye: “other” above all in the sense that a space informed by human consciousness gives way to a space informed by the unconscious (see translator’s note —ed).

Of course it is obvious here that nature does not mean what is called the natural world or trees and plants. In Atget’s case, “nature” could be substituted with the words “the city,” or “material reality.” I wrote before that I feel that I cannot enter into Atget’s photos. But this is due to the close relationship between feeling the naked hostile stare of material reality and the sense of disorientation we feel encountering a world exceeding all “human significance” that we have forced upon it. A world which was produced conversely from the fact that Atget always shot photographs as an artisan, discarding all a priori images of the world. The resulting influence of Atget on the surrealists, and on the contrary, what drew the attention of the surrealist artists to Atget’s photographs, was due to these acts of differentiation and the defamiliarization effects they produced.

If we consider that what gave rise to surrealism as a movement was an era that had begun to fundamentally question all values in the wake of the collapse of the world as a pre-established harmony following World War I, we can fully comprehend the fact that in order to reexamine the world and their own positions in it, young artists set out to return material things to the world of material things and to question piece by piece the entire system of meanings, values and images that had been historically constructed up to that point in time. It was also an effort to rescue humanity by rightly locating humanity’s position in the world through the act of thrusting things distinctly back to the side of material things. Considered in this way, we can perhaps begin to understand why Eugène Atget’s photographs began to receive the attention of the surrealists. The illusory atmosphere and surrealistic sensation that wafts through the photographic images of Atget emerge from the naked material things that peer out from the fissures of humanistic meaning.

However, photographers since Atget, the so-called photographers as the “authors” of modernity, have taken a completely different direction away from Eugène Atget. That is, their struggle to remake the world in accordance to their images, holding onto their own personal private images of it in order to establish their selves as “artists,” is demonstrated by history. We could say this of many photographers including Alvin Langdon Coburn’s abstractionism, László Moholy-Nagy’s photograms, Albert Renger-Patzsch’s Neue Sachlichkeit (“New Objectivity”) and Edward Weston of Group f/64 as well to name a few at random.

Nagy, Patzsch and Weston have certainly struggled to expand our field of view by turning their eye on the minute parts of reality and material objects to present and enlarge them. But ultimately these merely culminated in dressing up reality with another new aesthetics and image. Furthermore, the so-called straight photography of photojournalists and reportage photographers such as Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen and Dorthea Lange, seek out from reality the meanings of “poverty” and “suffering” to merely extract and display literally whatever meanings they presume to find therein. Of course this is putting it a bit strongly. There must be a more suitable commentator on these histories than me. But if I might dare to state my own biases, among the century long history of photography, I think the only person comparable to Eugène Atget is Walker Evans who photographed the impoverishment of American rural areas following the Great Depression of 1929.

The real question is what is the photographer exactly? As a photographer myself, whenever I think about Eugène Atget I always end up facing this question. This also raises the question, does the photographer as “author” exist? Clearly photographers do exist today as vocational specialists, I myself am a petty ranking member of these. Yet, if we consider that the “author” is someone who literally “produces” the world by asserting the “self,” there is no need for the photographer as author to exist. This should be clear from what I have already written on Atget thus far. Precisely because he did not have his own image, Atget succeeded in invoking the world and reality. Because he lacked any a priori images, Atget laid bare the world as the world. But for us, who already “fully know” the world all too well, can we still nakedly manifest reality like this or not? If we suppose it is possible, then there is no other way than to start out by first discarding one’s self.

Ben Vautier, the contemporary French artist that fervently writes slogans, said, “If one intends to change the world, to change art, first they must discard their own ego’s.” That’s it exactly. It is no longer possible for the photographer to gain anything by asserting the individual self. By doing so, this is merely the story of how one at most might be able to succeed in joining the ranks of those photographers of the system and the artists of the system found in the continuously drifting course of photographic history. Ultimately, however, these have been enclosed by these systems, given the so-called official approval as the “sacred artist.” In a lecture entitled “Literature as Institution,” Hans Magnus Enzensberger notes that until the era of Guy de Maupassant, literature possessed a certain normative social capacity—the power to influence the shared sense of material values, aesthetics, morals—yet in the 20th century, with the growth of productive capacities that brought forth a variety of mass media, like photography, radio and television, literature lost the power to regulate the consciousnesses of the masses; the unconscious. What’s more, he describes the literature that can still endure today as “the literature of the catacombs,” that has become the prized possession of an extremely limited and privileged few. This precisely indicates the state of photography and of photographers to come from now on.

Photography “as art” will be placed in the hands of a privileged few. And at the same time, this sort of art-photography will become increasingly divorced from reality and history, and in proportion, acquire an increasingly “sacred” character. However, these few will not be able to obtain the potentiality that photography has by its very nature, to expand our perceptions, and to lay the world bare (precisely in the way that Atget’s photographs do). On the contrary, it is certain that the intrinsic function of photography will been grasped by the masses more strongly than in recent photography, contingent upon the development of film technologies. I said the masses. This does not refer to the “amateurs,” the bad imitators of the “authors” of the day. These “amateurs” are the colossal reserve army of “authors.” They just carry out the bad extended reproduction of the aesthetics and images brandished by the “author.” The masses I refer to precisely indicate the anonymous masses. It is within the specificity of photography’s intrinsic nature, for which it matters not who took the photograph but how it reveals the world, that photography will be evaluated and at the same time will acquire its true anonymity. The anonymity I speak of can only be achieved from within this kind of historical flow.

The discontinuation of Life magazine surely tells us one aspect of the fact that photography has been surpassed by television and other more advanced media. But to be more precise, the photographic method like that of Life, a form of communication where the reporter as the spokesperson of the masses unilaterally conveys “true reality” to the masses, has disintegrated as far as photography is concerned. This kind of form has been taken over by television in a much more centralized and monopolistic manner. That being said, does this not also suggest that photography, at least potentially, has drawn much closer to the side of the masses?

Will photography not proceed along the polarization between the photography of “the photographer within the catacombs” and the photography of the masses from now on? The photography of the masses will surely be a kind of photography like Eugène Atget’s photography. A photography assessed by how the world is condensed in its true form on film in an instant and not a photography assessed by how the world can be captured by the personal image of a single person. It is this sort of photography that will clearly display the intrinsic function of photography all the more on the horizon called “society.”

The first chapter of Eugène Atget’s photobook, Paris du Temps Perdu is entitled, “Looking at the City.” But now, this must be properly restated as “the Look from the City.” This is because these are not images of the city, images of the world grasped by means of a gaze concentrating on the city from a firmly established ego, but rather photographs that have succeeded in a curious inscription of the world and the city that leap at us from that side, with what might be called a vacuum or concave eye.

In this sense, for us photographers, Eugène Atget persistently continues to ask us to return to the starting point and reconsider the questions, what is the photographer, what is photography?

Translator’s Note: Emphasis is Nakahira’s. Walter Benjamin, “Little History of Photography” in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings Volume 2, 1927-1934 (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001), 510.

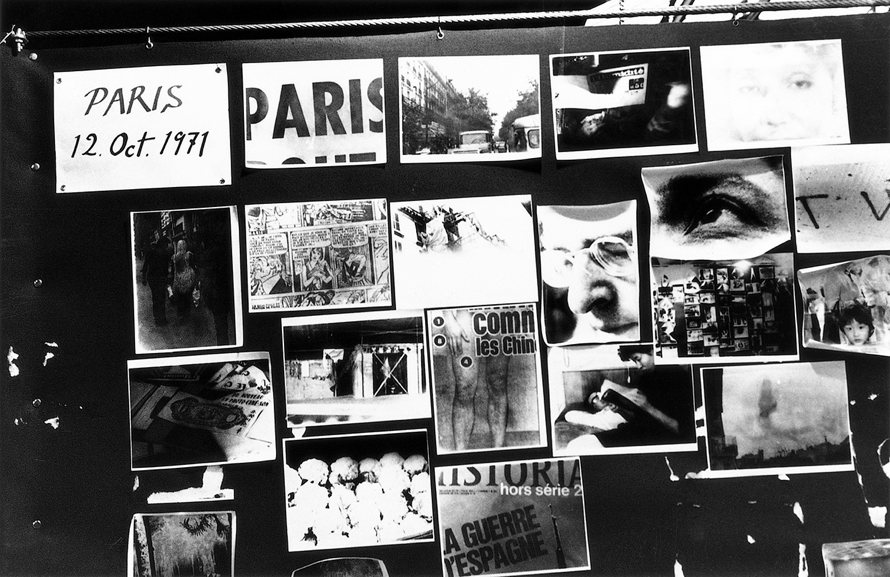

First published as “Eugène Atget: Toshi e no shisen aruiwa toshi kara no shisen” [“Eugène Atget: Looking at the City or, the Look from the City”] in Asahi Camera, November, 1973. It was later included in the book coauthored by Takuma Nakahira and Kishin Shinoyama, Kettō shashin-ron [Duel on Photography] (Tokyo: Asahi Shimbunsha, 1977) with minor revisions by the author. This translation is based upon the version appearing in Duel on Photography.

Copyright © 2010 by Takuma Nakahira and Osiris. Translation copyright © 2010 by Franz K. Prichard