You grew up hearing about the “Ghost Army” from your father, William Sayles. What’s your appreciation of those stories like now that you co-authored this book?

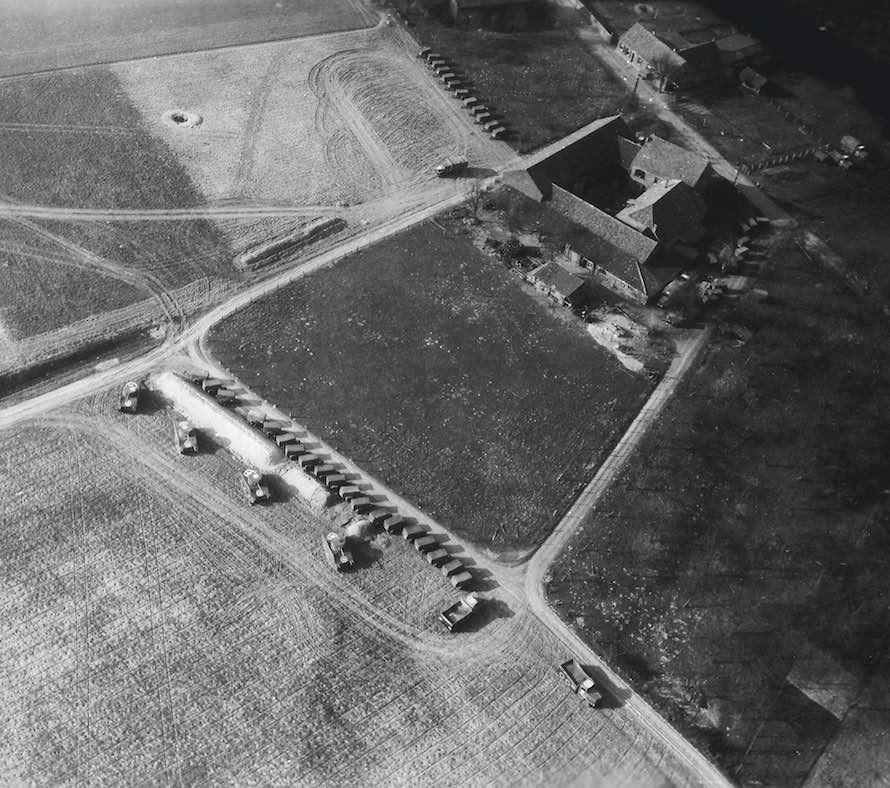

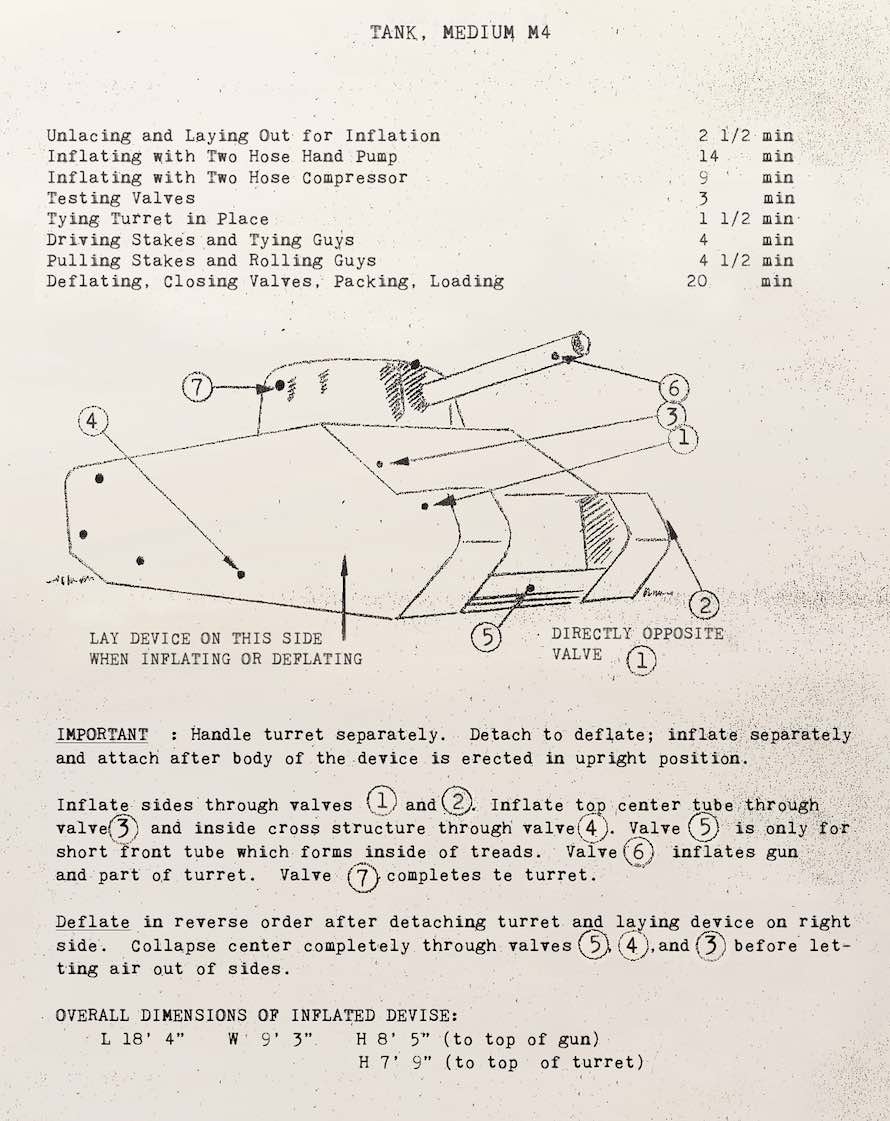

Elizabeth Sayles:My father told us very entertaining stories of his time in the war, which contrasted sharply with what some of my friends’ dads had been through. His stories focused on how they would inflate the tanks at night, or how they would impersonate other army divisions. Or how Bill Blass re-sewed his uniform so it fit better. But after working with Rick [Beyer] on this book, and other projects, I see how dangerous their missions really were, and also how effective. So I am very proud of what they did.

I’m not sure they actually realized the scope of some of their deceptions. For example, they were just told to “set up dummy tanks here,” or “drive around town over there and pretend to be 6th Armored division.” But they weren’t necessarily told what the big picture was. My father actually learned a lot from watching the Ghost Army documentary and reading the book.

TMN:In your research, were there stories you hadn’t heard before, that really surprised you?

ES:There was so much I learned through working with Rick on this project. Rick had contacted my father in the late ‘90s to interview him for the Ghost Army documentary. I hadn’t thought about those war stories in years, but I got interested in them again. Eventually Rick and I joined forces to mount a couple of art exhibits of the original artwork of the men of the Ghost Army. And then we collaborated on this book.

Most of the logistics and operations I had no idea about, but what was the most surprising to me was how much time they spent on the front line. I had no idea that they were right where the fighting was going on. They carried out several missions inside Germany, sometimes very close to Panzer divisions. They barely escaped the Battle of the Bulge, spent freezing nights sleeping in the cold in Belgium, Germany, and Luxembourg. And they were even shelled. My father had never told us any of that.

TMN:The tricks the unit pulled off weren’t just inventive, but effective as military maneuvers. Did you father and his colleagues see themselves as artists first? As soldiers?

ES:I think they always thought of themselves as artists first. The Army’s rules and bureaucracy were a source of frustration for most of them. Many of the ideas for the deceptions came from the men themselves.

TMN:Lots of the maneuvers were highly innovative.

ES:They innovated as they went along. They decided at one point to set up a fake headquarters, with fake MPs and even a fake general (which was definitely against Army rules). But it all had to be done perfectly and with precision, because the Germans were hard to fool and the consequences would have been dire if they’d been found out. But they never were.

TMN:For a long time, the Ghost Army’s achievements were classified information. How did your father adapt to civilian life? Was it difficult to carry the secret?

ES:My father was very happy to come back and resume civilian life. I think they all were. They were eager to restart their lives, begin their careers, and get on with it. I’m not sure he knew that it was supposed to be secret because he told us about it when we were kids!

TMN:Talk about the art produced by the group. It has the feel of close reporting, almost journalism, in the way that artists used to trail armies and work for the newspapers. There’s also the intimacy of the men being among one another, as both artists and soldiers, sharing this harrowing experience.

ES:The artists who were sent to the front by magazines and newspapers had only one job, and that was to document the war in paintings.

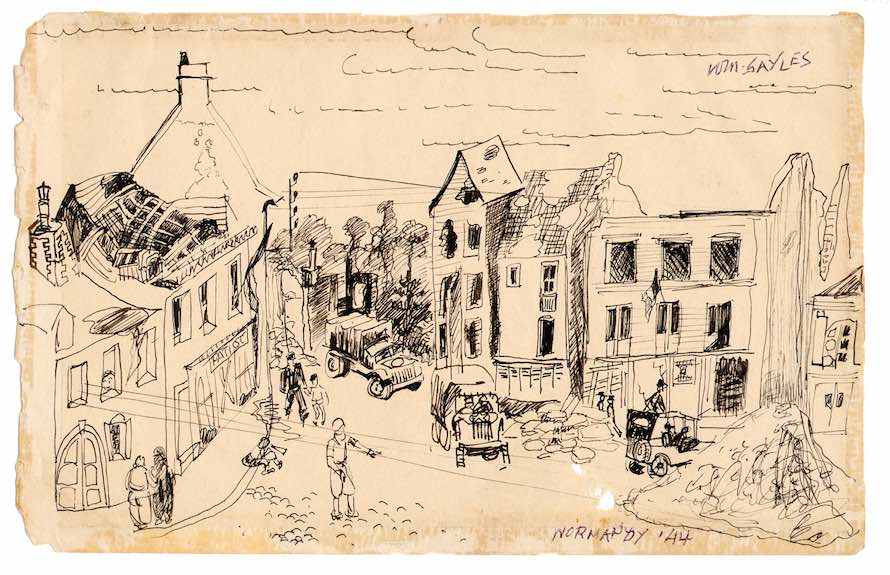

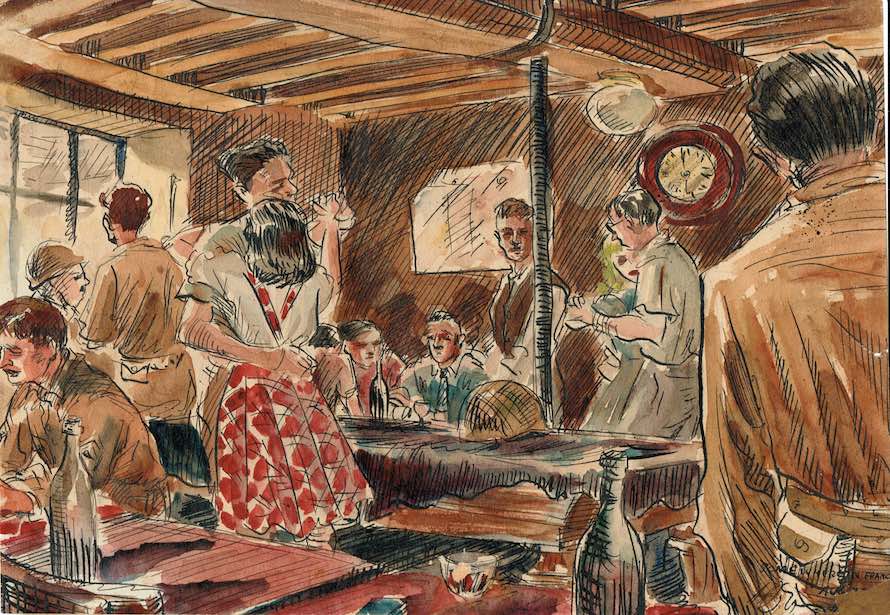

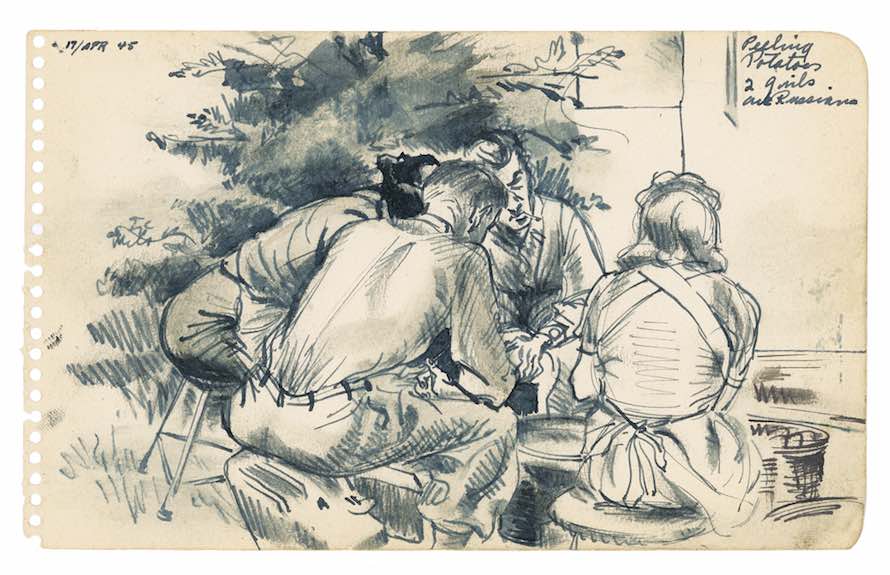

The artists of the Ghost Army, however, drew and painted in their down time in order to keep their sanity, and also because they were just in the habit of drawing all the time. I think for most they weren’t solely interested in documenting the war, they just drew what was there. They drew the shattered villages they passed through, and the people, and each other.

The artwork is amazing for how accomplished it is considering how young most of them were. Many of them were in art school at the time they enlisted, and they just carried their studies into Europe. They practiced drawing and they learned from each other. Ned Harris, who was 18 when he enlisted, learned how to use watercolors from Arthur Singer, who was already a working illustrator. He swears he learned more in the Army than at school. It’s interesting to see how several men would paint the same scene, but in different styles, and how some of their styles began merging.

In art school they were studying the theories of the German Bauhaus, and of course all the painters of Europe. The idea that they now found themselves at the center of the art world was actually very exciting to them, despite the fact that it was a war zone and they were sent there with fake weapons!

TMN:That’s amazing.

ES:My father was excited to go. It was the only way he would ever get to Europe because he had no money. When they got to Paris, of course all the museums were closed, but they could still experience the city that has such a rich artistic legacy. They even visited the brothels so they could draw nudes, ala Toulouse-Lautrec.

And they saved their work. They carried it across Europe with them, sometimes shipped it home or traded it with each other. It has been interesting tracking the work down. And it’s exciting that we keep finding new pieces.

TMN:The variety of the men’s backgrounds, including all these significant artists, is striking. Did the group maintain connections over the years?

ES:The Ghost Army was an interesting mix of artists from the Northeast and a large contingent of coal miners and mechanics from the South.

After the war many of the art students went back and finished their degrees and became a network for each other as they began their careers. My father and Arthur Shilstone had a design studio together in New York in the ‘50s. Bill Blass, Jack Masey, my father, and others all kept in touch for awhile. Ned Harris and my father are neighbors and remain friendly to this day.