According to L.A. Weekly, there are more cars than people in Los Angeles. This has lead to a whole new spectrum of human expression, much of it perilous, like road rage on the 405, and some not so much, like the car note—those scraps of paper tucked beneath windshield wipers that are neither parking tickets nor car wash coupons.

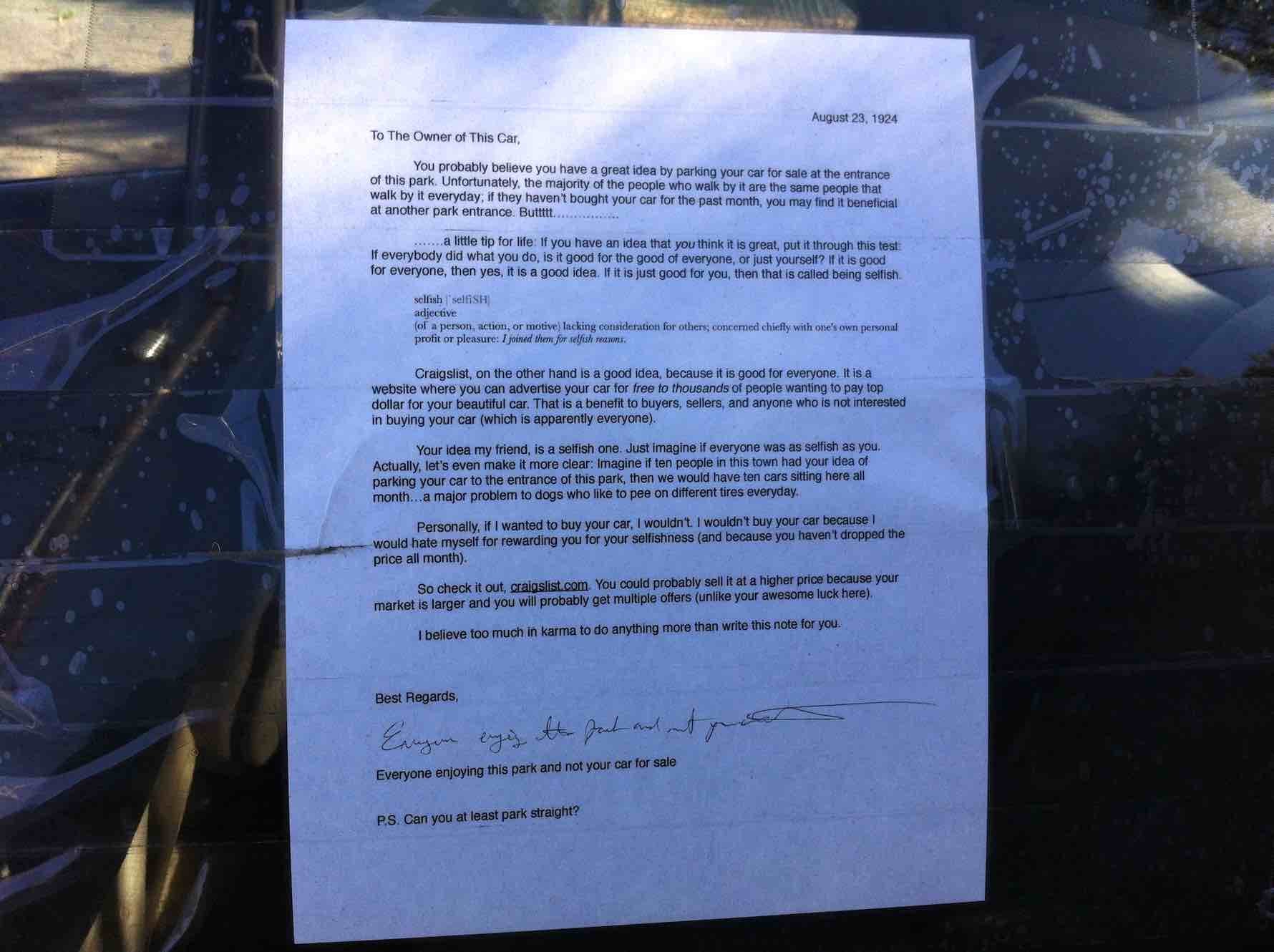

I’ve been accruing car notes in my spare time for several months. I don’t steal them from cars, I wouldn’t do that. Instead, I record their content. Sometimes I photograph them with my phone. The note that began this journey was from a car parked at the lip of a dead-end residential street, near the entrance to a park in Los Angeles, where I live. It wasn’t a bona fide parking place. The parked car contained two notes: One was a “For Sale” sign, and the other a typed letter taped onto the outside of the driver’s side window.

I collect them because they’re one of the increasingly rare non-digital forms of publicly displayed communication, like supermarket bulletin-board notes, London Review of Books personals, Church program social columns, The Penny Saver, etc. Many car notes are structured like a traditional letter, i.e., they address someone, or something, and they largely contain complete sentences. Most are written by hand. This makes them something of a specialty in contemporary human interaction when texting and messaging have essentially turned the form into fragments.

Some notes I’ve come across are simple and self-aware: “Hey, I know my car is taking up two parking spaces, but the gardeners are coming to cut down the dead oak tree—you wouldn’t want to park here anyway!” I asked an A student who’d taken my literature class to read the subtext and let me know what she thought the note was really saying. Her analysis? “Go fuck yourself.”

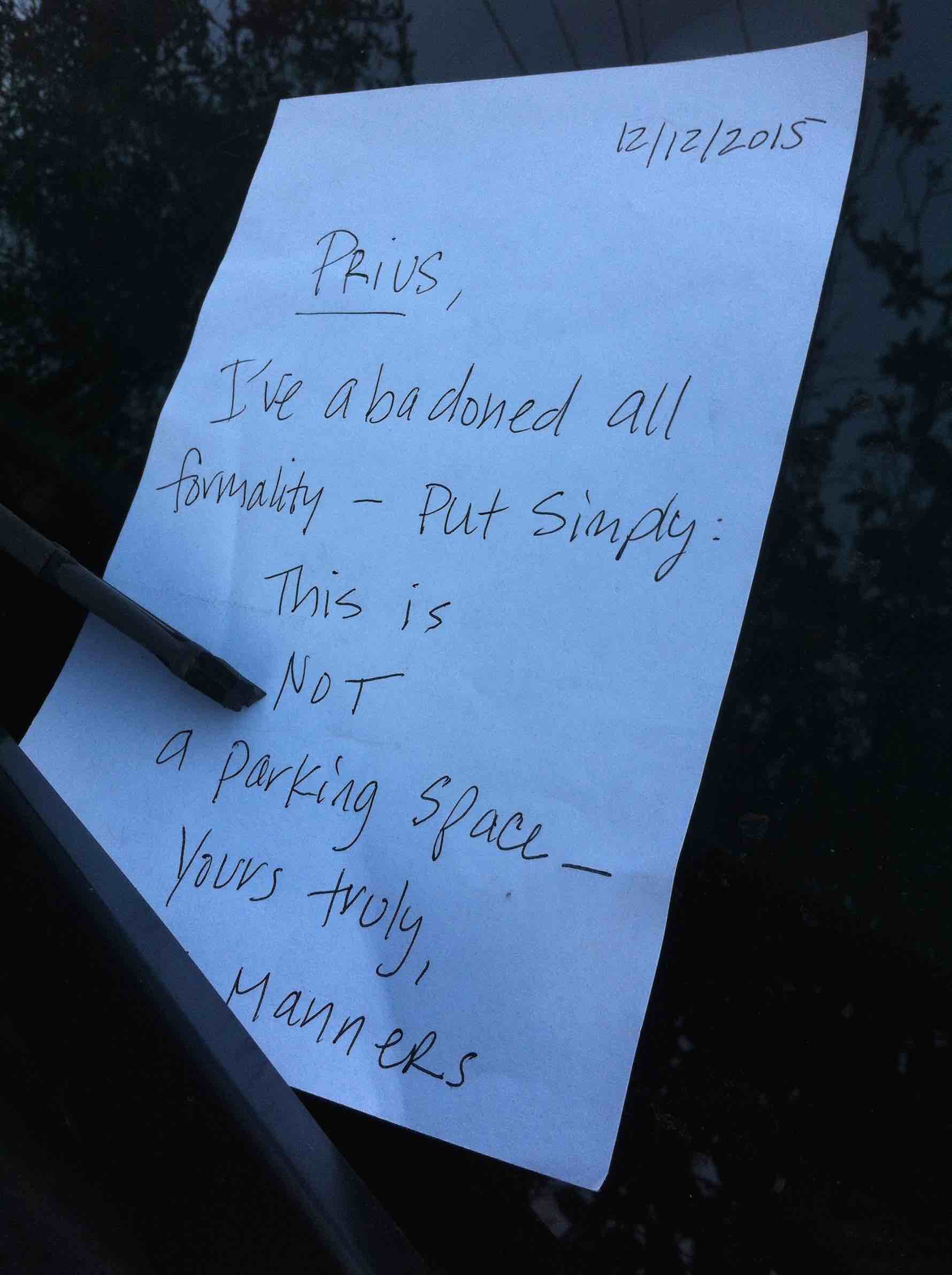

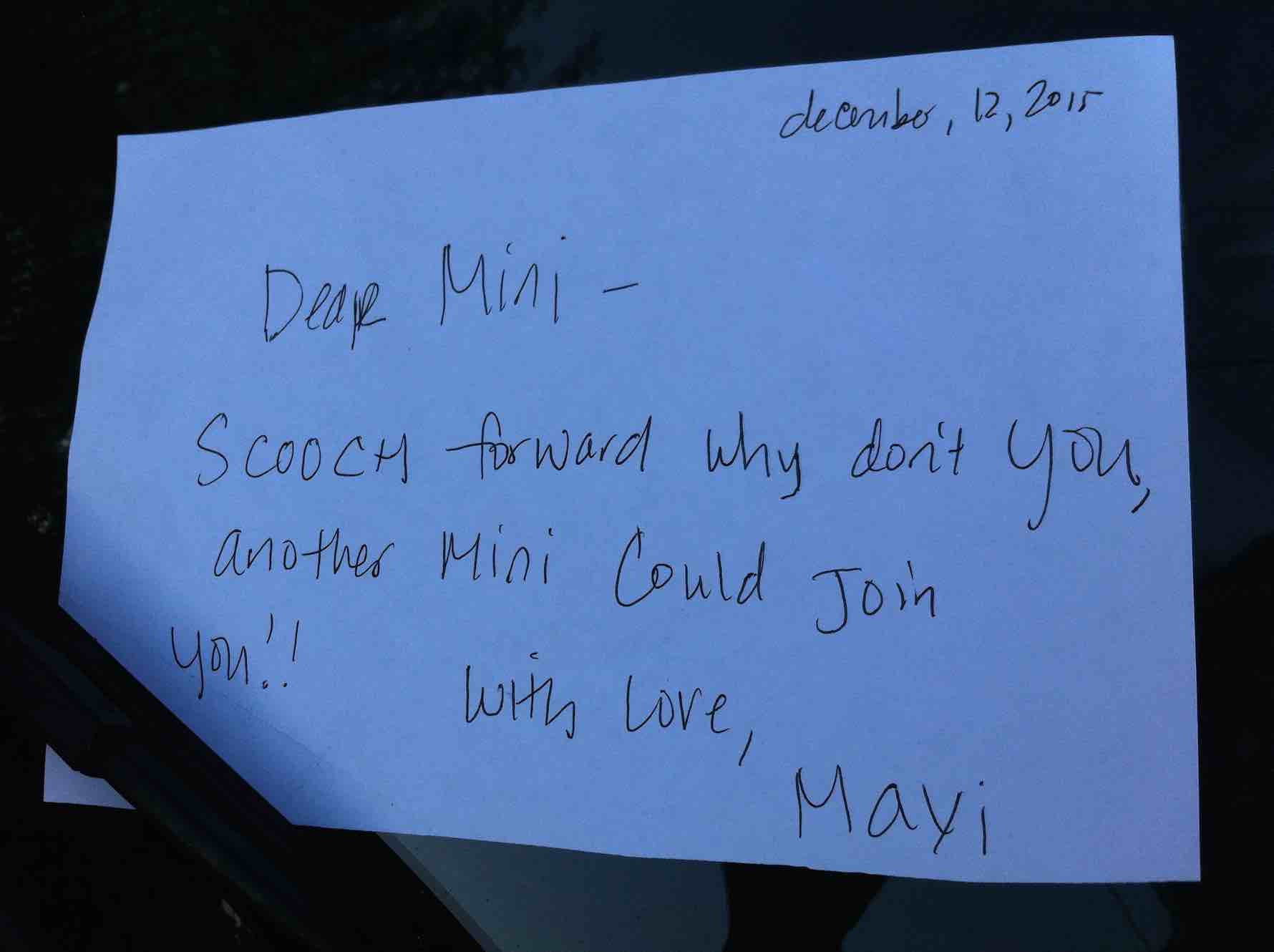

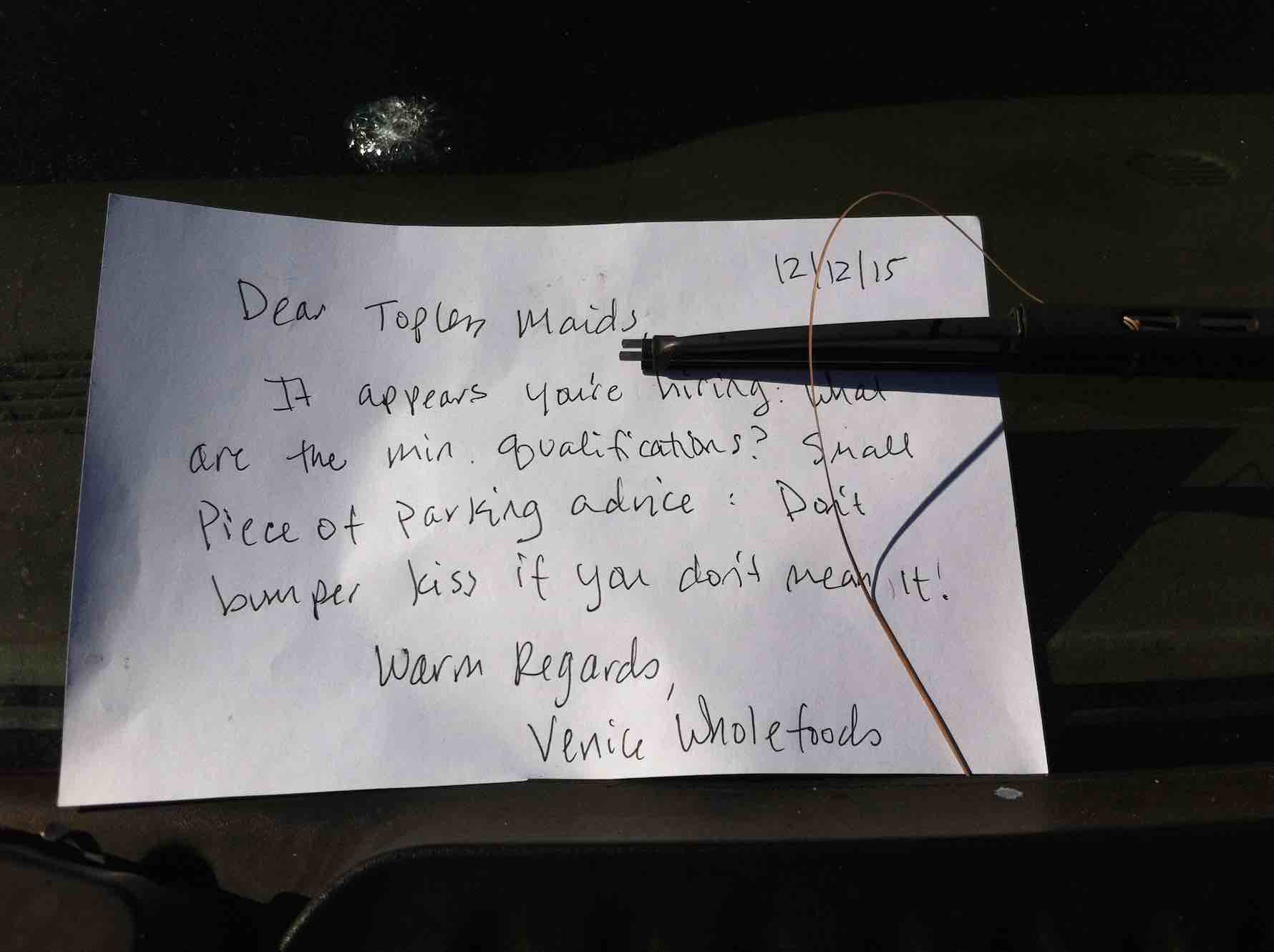

Others I’ve found broadcast their messages with a more acerbic flair:

It’s got me thinking about how we express ourselves when communicating with strangers. Social media can’t reach out to the person sitting next to you in traffic. There isn’t license plate recognition on Facebook. In these particular situations, the most direct and efficient form of communication is the good old fashioned letter, with all its formalities. After months of observing this phenomena, I decided to entertain the full range of what letter writing could accomplish, and to finally express all my feelings about living in a city where cars are king. In December, I traveled across the vast city of Los Angeles in search of any and every opportunity to leave car notes for strangers.

Etiquette, as defined in 1924’s anonymously authored Standard Book of Etiquette, is “the accepted conventional form of good manners required by the customs of polite society.” Which, in LA car culture, is hardly the norm. A Los Angeles driver will give you the finger because they cut you off. Why do manners exist? Mannered communication is meant to allow people a way to express themselves without disrupting the social order, and this succeeds though disingenuously. At least that is what I teach my university students when we read The Importance of Being Ernest. Oscar Wilde spent his life’s work revealing the satirical edge of these invectives, specifically how people manage to use them to achieve their goals. Of Wilde’s comedy of manners, scholar David P. Pierson says, “One of the underlying assumptions of these dramas is that people primarily act out of self-interest and as such, they have few commitments to anybody or anything but themselves.”

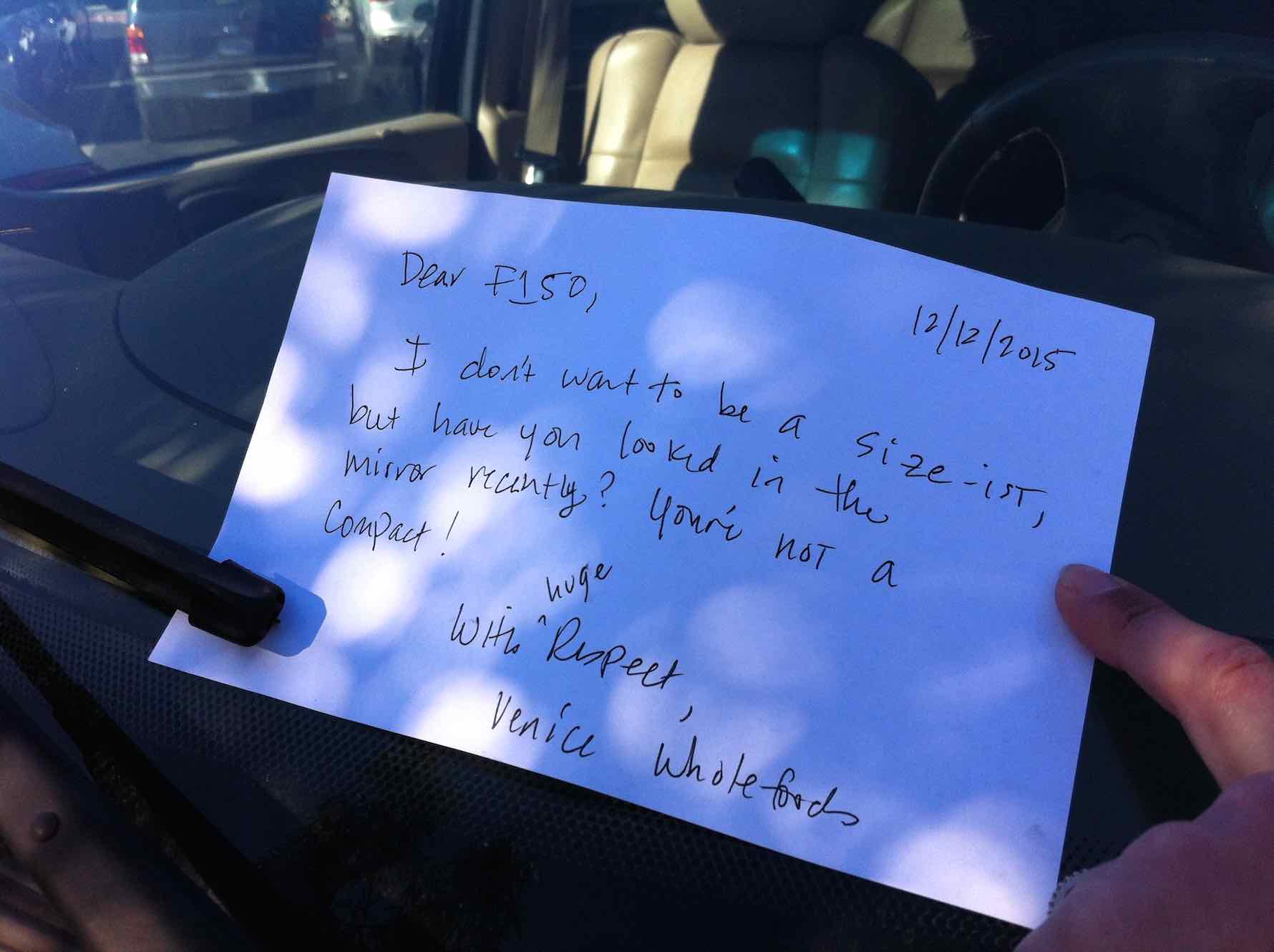

Take that F-150 I found parked in a compact space at the Whole Foods parking lot in Venice. A typical Los Angeles scene: Congratulations on getting your truck into that spot, and thanks to you no one else can open their doors.

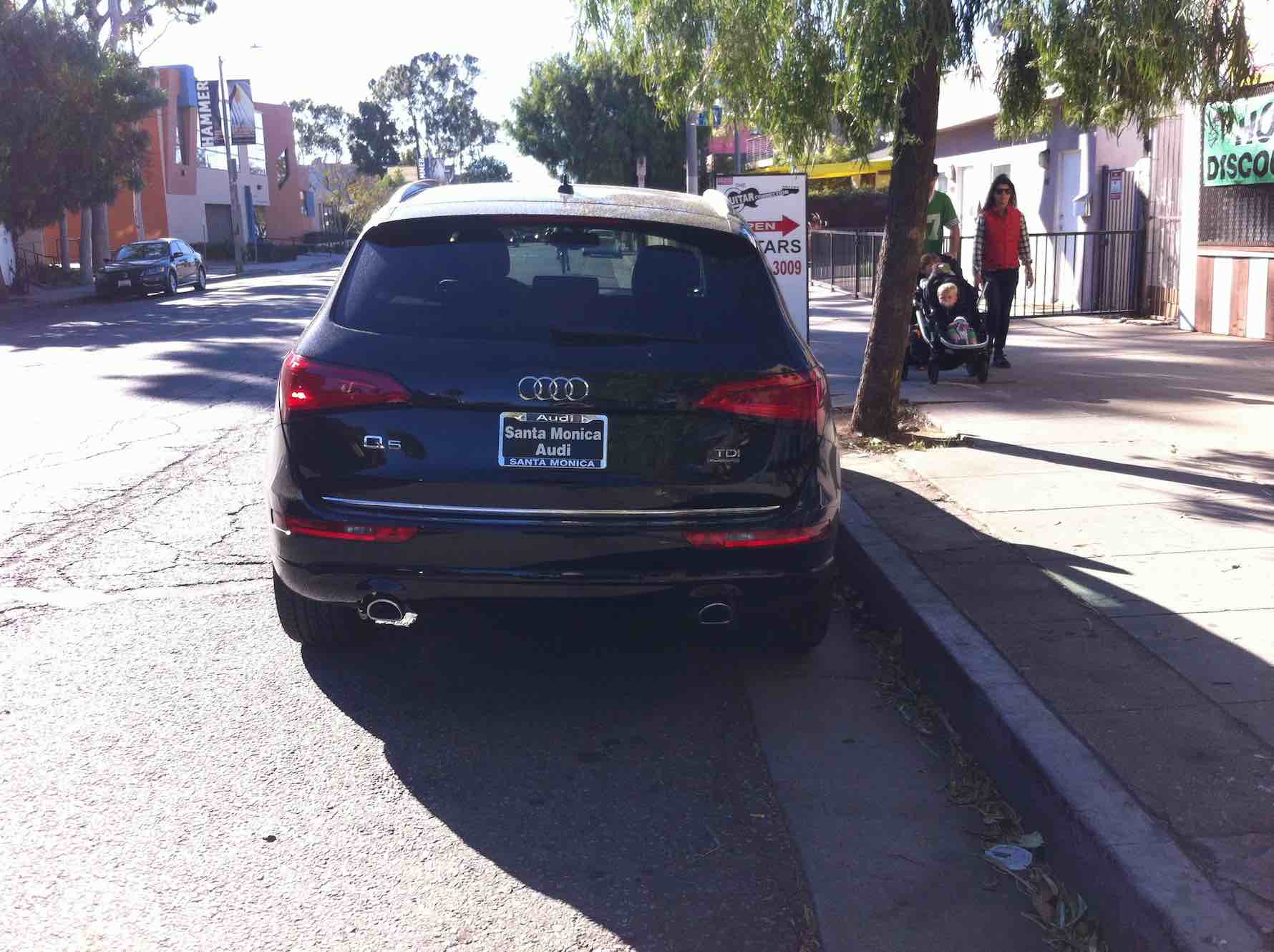

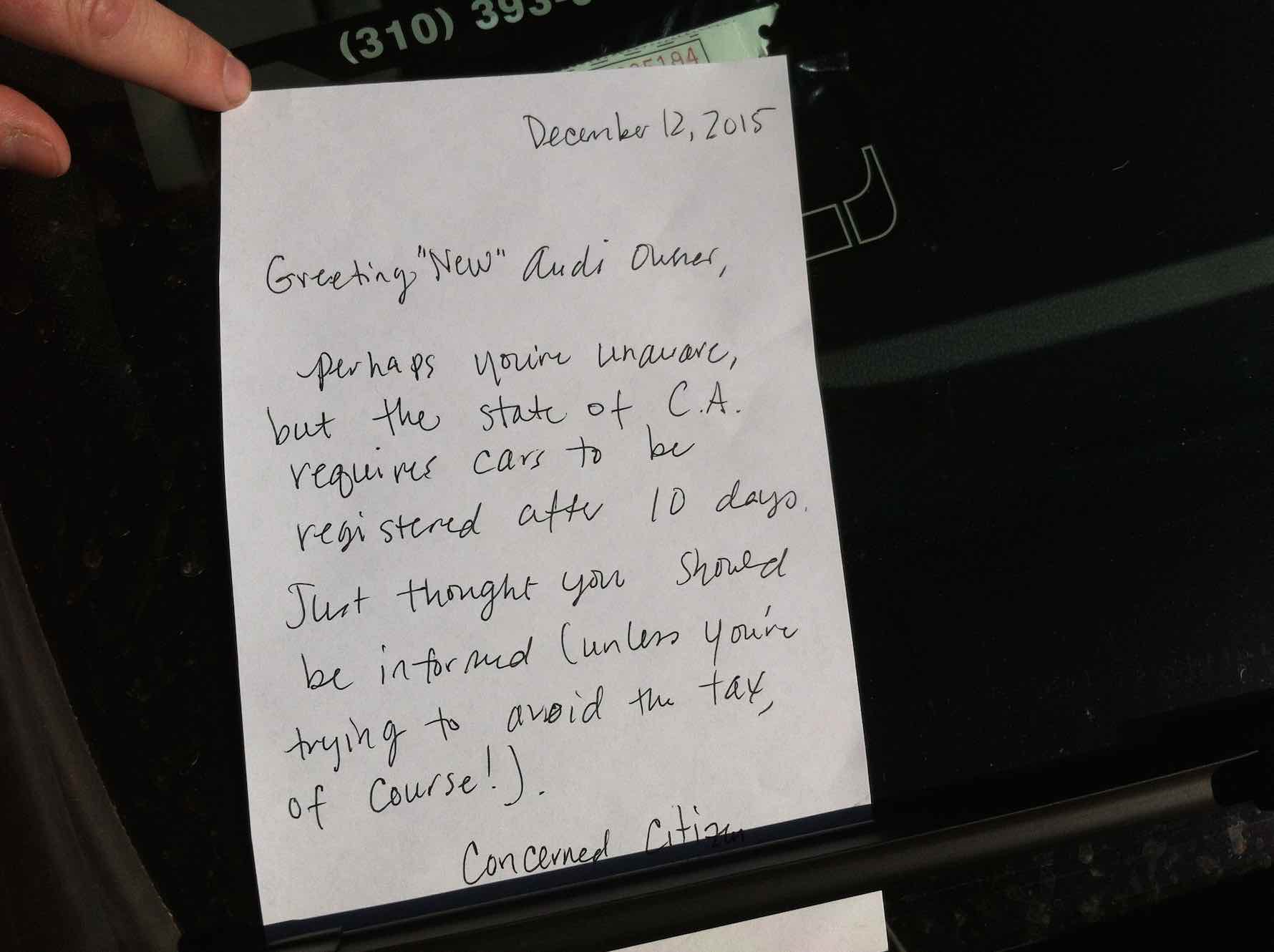

Manners, in addition to being about getting what you want, are also about righting wrongs. Above is a prime example of somebody who has the money to buy a luxury automobile, but presumably doesn’t want to pony up and pay the taxes to register it.

I’m snapping a photo of the note I left when a young couple comes up to read it. The man says, “That’s really nice that you’d leave a note. In San Francisco, nobody would leave a note.” The irony of course was that this refined mode of behavior served to appear as a kind gesture, when really the note was a way to vent my frustration at this common LA scofflawery.

In LA you are your car—Swingers, anyone? This emphasis on cars makes the car note an especially vital mode of articulation. Not to mention it’s a legally approved method of communication between car owners when only one driver is present after an accident. According to the California Driver Handbook, “If you hit a parked vehicle or other property, leave a note with your name, phone number, and address in or securely attached to the vehicle or property you hit.”

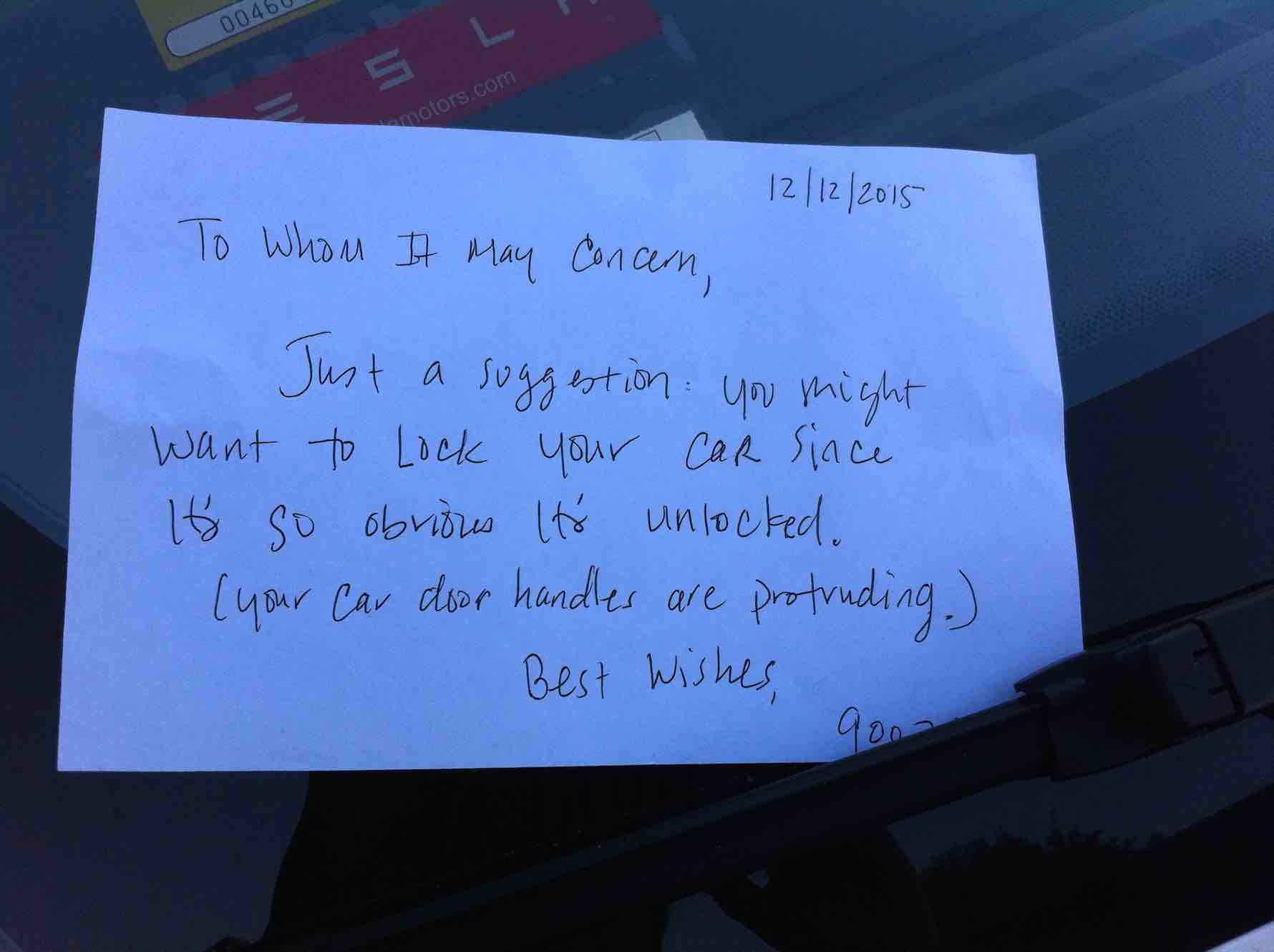

When I saw that Tesla in Beverly Hills with its doors obviously unlocked, I had to intervene, though mostly I used politeness as a sanctioned excuse to touch it. The wealthier the area, the freakier this project became. The stakes were different in that part of town, with its clean streets, heavily adorned women, and drought-inappropriate greenery. I had a TV in the '90s; I know what 90210 is all about. I simply don’t belong in Beverly Hills, and there wasn’t any way to fake it, but no one could stop me from touching the Tesla. I got out my notepaper and nervously began writing. I carefully placed the note below the windshield wiper, making sure not to smudge the glass. Thank you, etiquette—without you I’d never been able to get away with it.

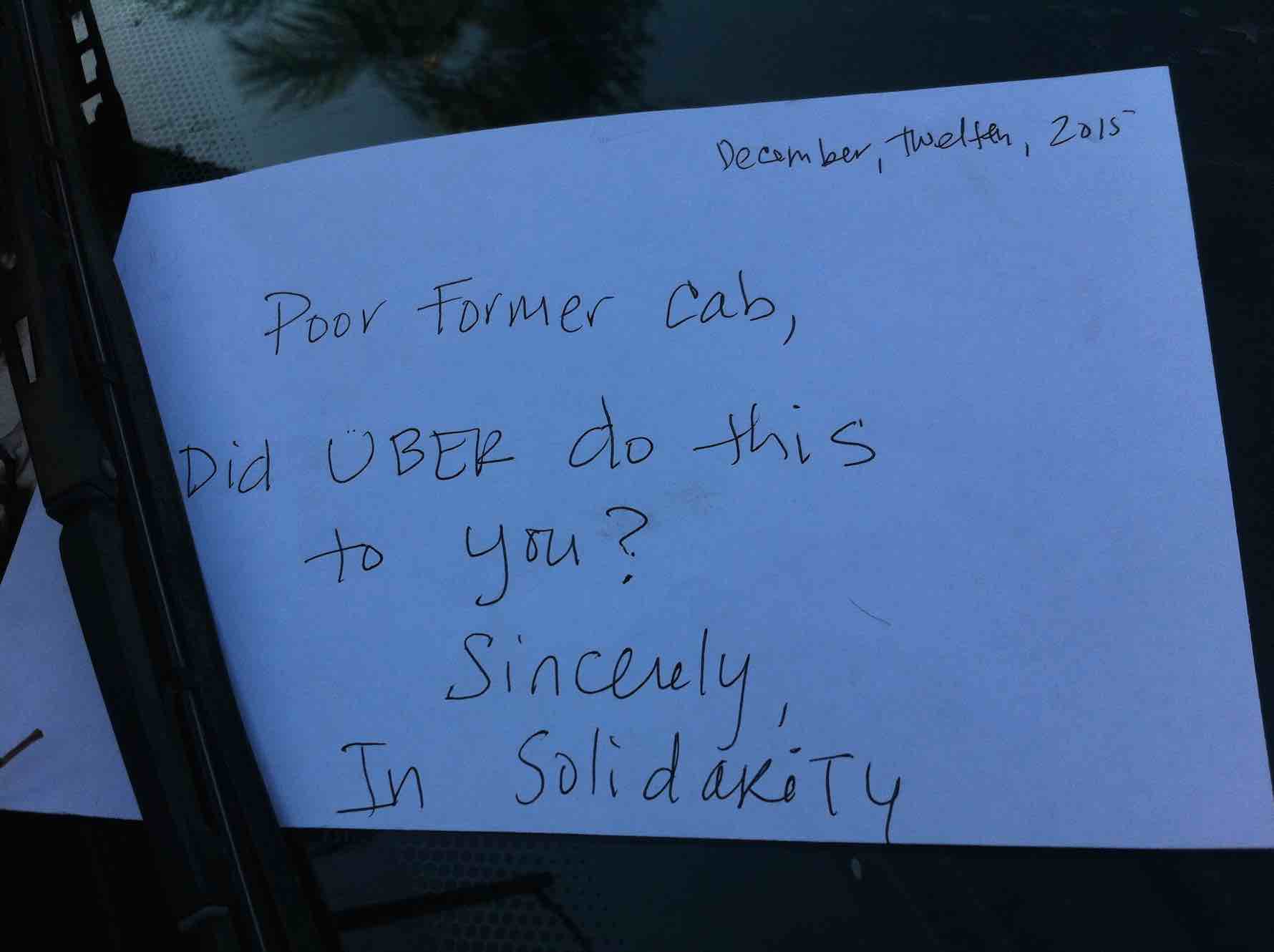

Then there are the cars that have taken a beating. They are plentiful in the City of Angels. And isn’t another component of good manners showing concern for the downtrodden? I empathized with the former taxi I found in Melrose Hill. Does it still get flagged down and taken for a ride?

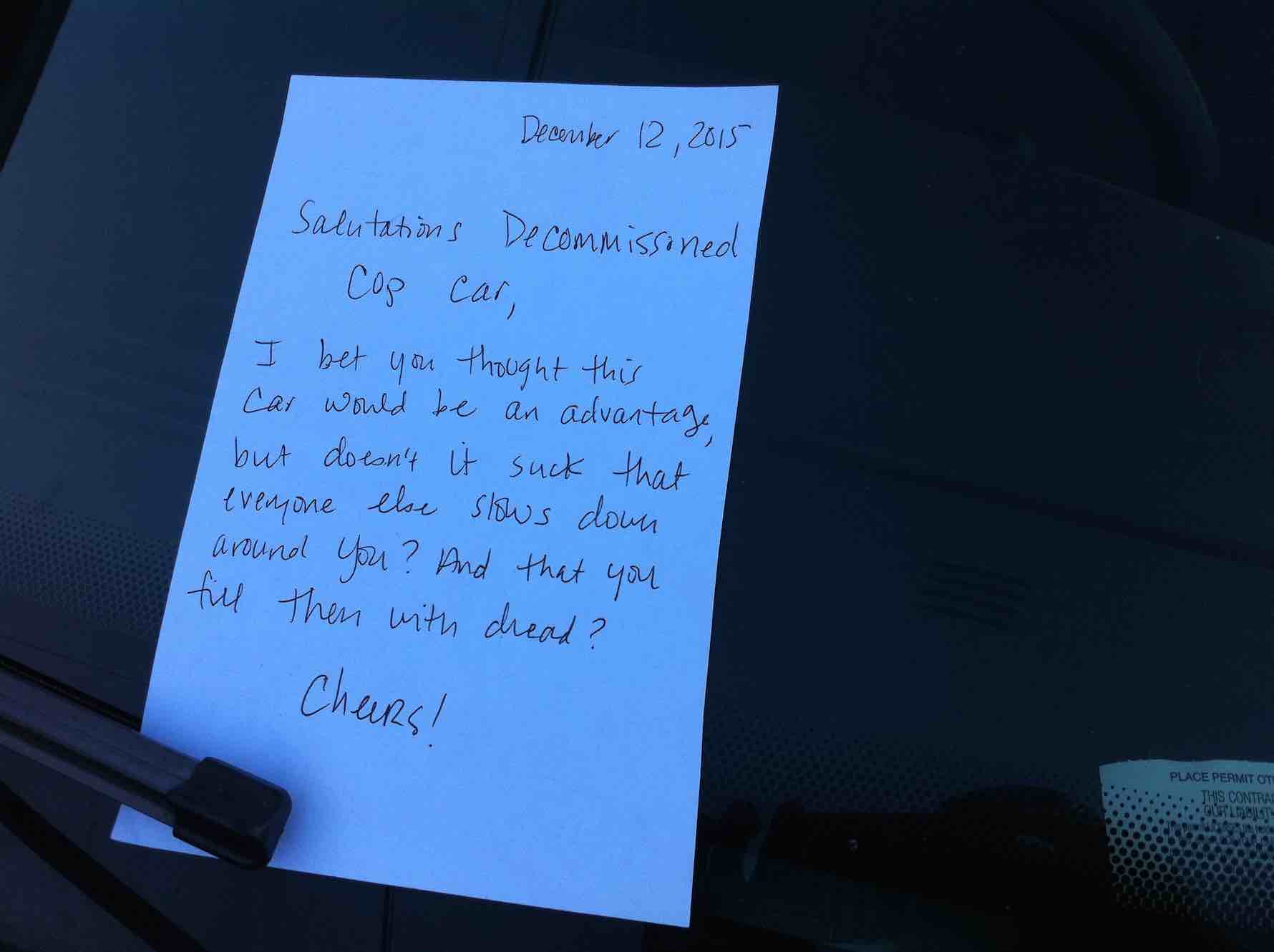

And the decommissioned cop car, is it an advantage or a hindrance? Does it mean the driver gets to break laws, or does he or she simply inspire paranoia in everyone else, thus obliterating any chance of having fun? The latter makes me think about the guy on my street in Echo Park, who owns one of these Crown Victorias (not pictured). He likes my Sheltie runt. We don’t exchange many words, but he always calls out “Miniature fucking Lassie” when I pass by with my dog. And I like him for his deadpan humor.

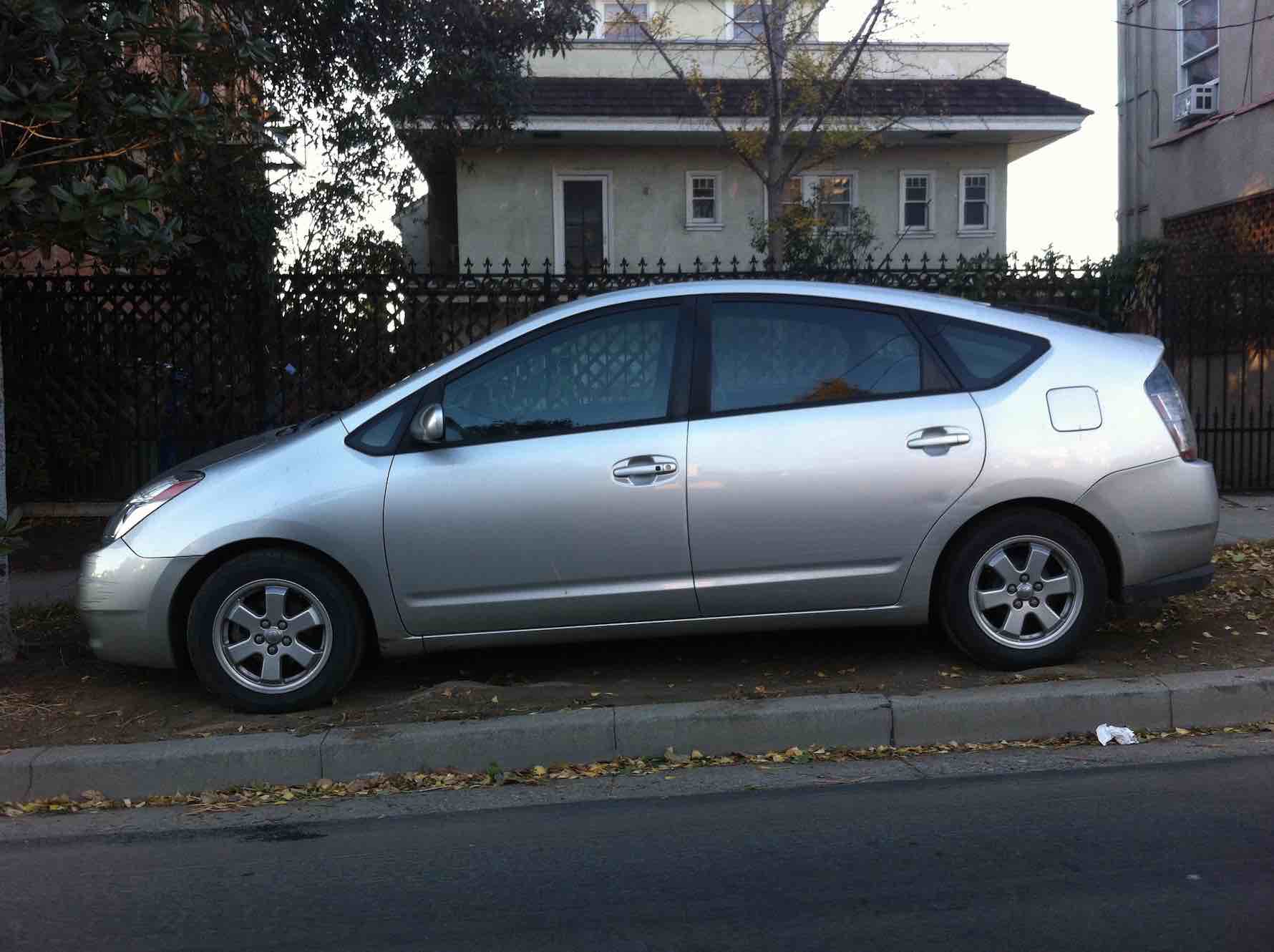

In Complete Letter-Writer for Ladies and Gentlemen, another anonymous book, published around 1907, to write a proper letter one is advised, “(1) Weigh your words, and (2) Never exaggerate.” Through a variety of letter templates, the book aims to give people a way to express their feelings without insulting anyone. The car note presents a great opportunity to engage with others; occasionally, car owners in LA just need a little nudge to get them back on track. If I’ve learned one thing from my Sheltie runt, who herds strangers like sheep, we all occasionally can use a polite reminder that we’re part of civil society. (Wink, wink, Prius, Mini, Topless Maids Van.)

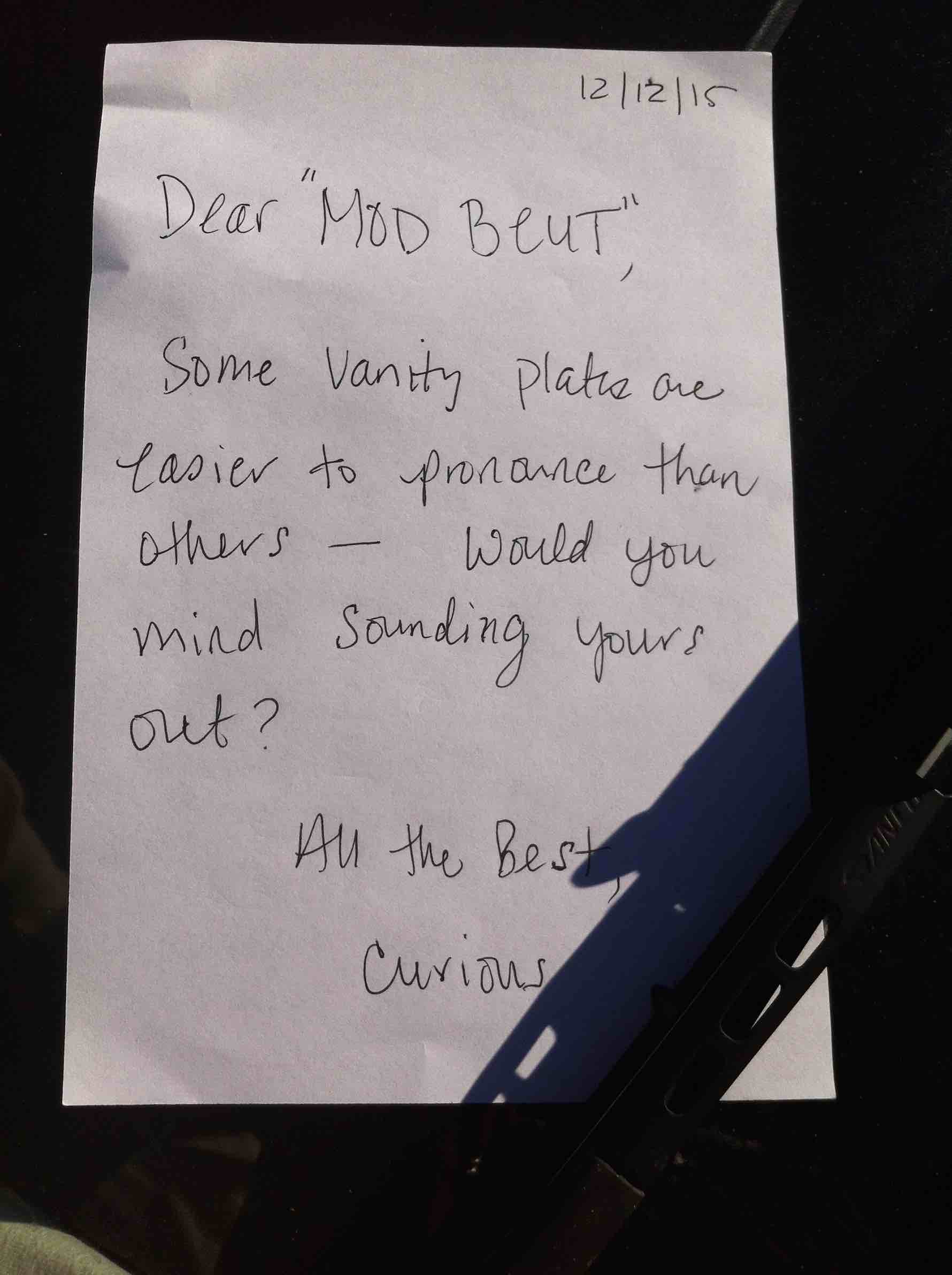

In a polite society, we’re better off not screaming obscenities at incomprehensible vanity plates since there is no sure way to tell if someone is famous or powerful or carrying a knife. Which is why the letter is the perfect means of expression, with its shielded directedness and its formal opaqueness. Inputting frustrations into a specific mold or template goes a long way to releasing pent-up rage, and there is some chance that the reader will receive the sentiment. I hadn’t yet paid the parking meter, and I was busy trying to finish my note to “Mod Beut” on the Sunset Strip—that stretch of roadway famous for tragic overdoses—when a county sheriff pulled up behind me. Things were tense. The other side of the street was bumper-to-bumper with star-spotting double-decker buses, full of visitors vying for a glimpse of Ashton Kutcher’s new baby. The clock was ticking. The sheriff sat there for nearly 10 minutes, watching me suspiciously as I tried to finish the car note. Anxious, I took a deep breath and thought, Oscar Wilde was persecuted too!

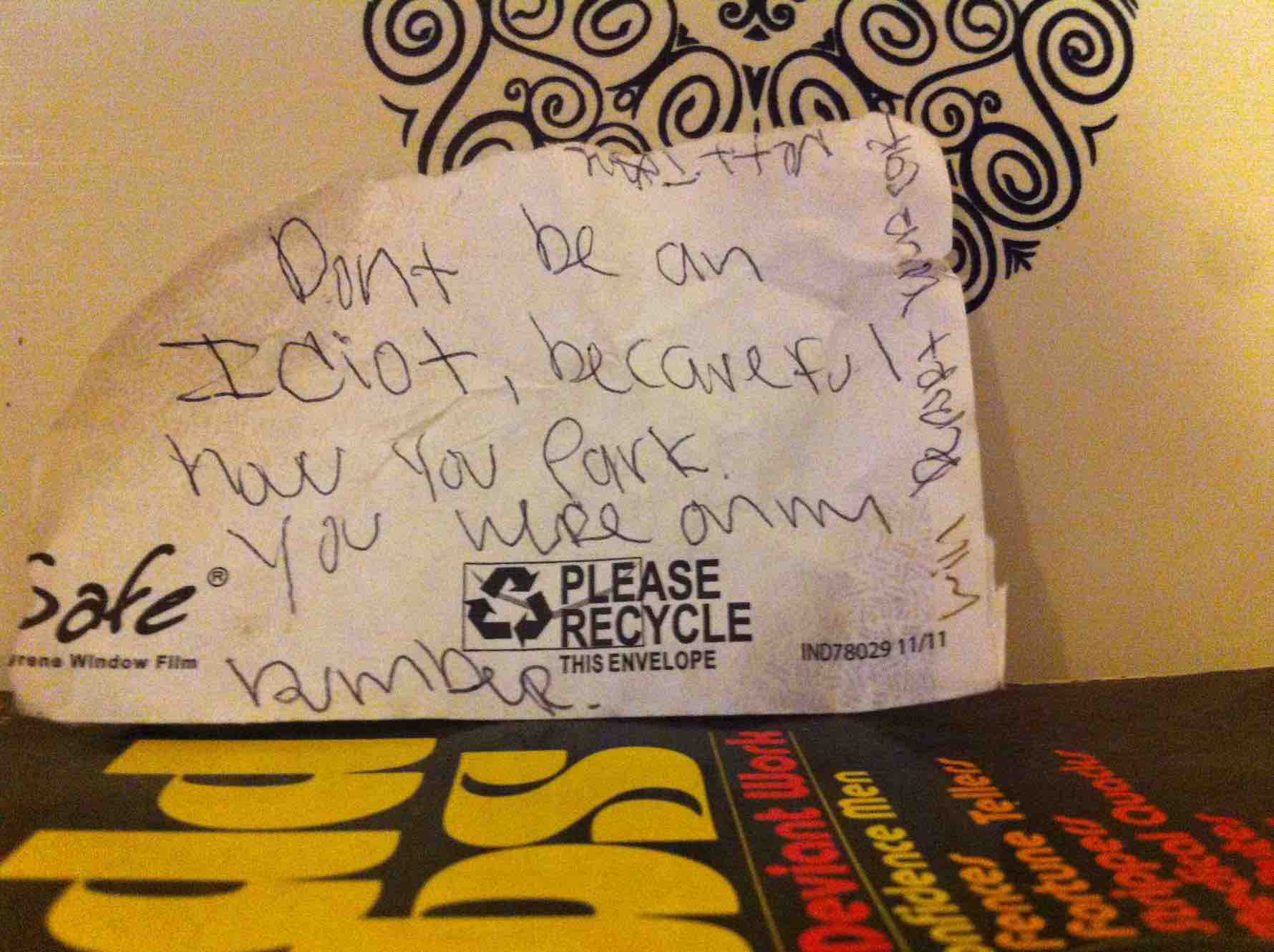

I received my driver’s license in August, at the age of 35. Many people wonder how I’ve gotten by all those years in this overwhelming car city, and I tell them I like bikes and buses and was trying to save money. Eventually I caved. I had to own up to the fact that my life would be made easier if I had a car. And everyone pointed to the falling gas prices. Time will tell, but I’m sure they’re right. Though it was within my first week of driving that I received my first and only car note. I was late to a birthday party and proud to have squeezed into a seemingly impossible space; parallel parking is not my forte. But I left the party to find this scrawled scrap beneath my wiper:

So much rage from a simple touching of bumpers.

Reflecting on a day of writing car notes that began at noon on the West side and ended at five on the East, I realized that maybe these notes were almost exclusively about the writer and not the receiver, and that a dose of satire when addressing the perils of driving can, in fact, be positive whether a note is intentionally humorous, or like the note I received for bad parallel parking, unintentionally. After all this time, we still depend on the letter, with all its conventions, as a way to adequately present ourselves. I find this to be a relief. As Wilde himself wrote in a letter from jail in Reading, England, where his escapades with etiquette had landed him—which I’ve escaped for the moment—“I didn’t write this letter to put bitterness into your heart, but to pluck it out of mine.”