by Chris Adrian and Eli Horowitz

Buy it at Powell’s »Syreeta McFadden: First, let me start off with a few caveats.

- I don’t do Christmas.

- The universe is a hilarious minx.

- “Sunday Candy” is my jam of the week.

- I’ve seen every episode of NCIS that has ever aired. I’m particularly fond of seasons six and seven.

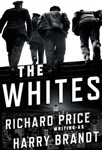

This is all to say that I could not tell you why I’d even agree to be a judge for this competition that will inevitably lead to some kind of dragging from book lovers. But I should also tell you that when I received my books, Richard Price’s The Whites and Kent Haruf’s Our Souls at Night, it was the Chrismakwazukkah (yes, this is a real holiday and it’s mine) present I didn’t even know I wanted. I knew that what would follow would be an impossible decision, but it was so right.

Guys, I’m from Wisconsin. Old people and crime procedurals are kind of our thing, I guess. I don’t need to watch Making a Murderer, I feel like I’m good. I used to volunteer at nursing homes in my hometown of Milwaukee, and we all watched Cocoon together while eating gingersnaps.

That said, I never saw the movie version of Clockers or read any Richard Price book before in my life. I was suspicious of the insistence of the pen name he uses for The Whites—it’s a bit meta. If it’s a Richard Price book, why continue the charade of writing as Harry Brandt? Even Sasha Fierce got dropped after one album to fully embrace the Amazonian cyborg feminist identity known as Beyoncé. Eventually I set the shade aside and soldiered through this book. Price-as-Brandt gives us that old-school hardboiled crime novel protagonist: Night watch manager Billy Graves is shocked out his humdrum state of maudlin suburban living ennui when an old and very cold case surfaces through the death of Jeffery Bannion. Billy used to run with a squad of cops known as the Wild Geese who ran the streets of the Bronx, and “in the eyes of the people they protected and occasionally avenged, walked the streets like gods.” The Wild Geese had long believed Bannion guilty of murder, but the wheels of justice seemed to turn in his favor. And like all squads over time, things fell apart: Billy accidentally killed a 10-year-old boy during a pursuit of another dirtbag, and his career has never been the same.

Here’s the thing though: Price-as-Brandt is situating this story in a very specific social environment right now, so there’s a kind of cognitive dissonance in looking behind the “blue wall of silence” and following a once-promising cop whose career was unraveled by poor personal decisions and an unchecked abuse of power. There were moments when I grew pretty impatient with Billy, and perhaps the book. I’m supposed to feel uncomfortable about that (and I do) because police work is gray and murky, the rule of law is fleeting in the eye of the beholder, good is a child’s fantasy. The Whites is a Crimey McCrime novel that I totally dig, with really compelling descriptions of the New York I pretend not to see except in Law & Order marathons or the occasional episode of Blue Bloods that catches my eye. But it’s also a bit of ghost story, asking us to assess the meaning of vengeance. Satisfaction in reading a crime novel comes when you feel like you can solve the puzzle and right the wrong, as Billy Graves does here. But at what cost? I worry about Billy, his wife Carmen and her undiagnosed PTSD, his dad, and his ex-Wild Geese homie Yasmeen, the Angelica Schuyler of this novel. My heart breaks a little for Pavlicek, Billy’s former police partner. Billy’s life is messy and the suspense is in how he reaches equilibrium without self-destructing.

Price-as-Brandt rushes into Sorkin-esque noir dialogue that occasionally mutes the drama for me. He doesn’t slow scenes down very much, because he relies on the voices of the characters for storytelling. It is clear that his ear for dialogue is inimitable. But when we do get a break from the characters’ snappy, shade-driven conversations, it’s in moments of breathless suspense following the trail of Milton Ramos, the bloodthirsty man seeking revenge against a member of the Graves family. This is where Price-as-Brandt shines:

To avenge his family, he would be destroying what was left of it. The Ramos family would go from two here to two gone, which is to say no one left. But what if instead of Ramos obliteration they—he—went the other way and doubled their number?

…

He was still standing outside his car, bat in hand, when Carmen’s brother suddenly came out of the motel, trotted to the Range Rover, and opened the passenger door. Victor grabbed a mini-recorder from the glove box, then dropped his car keys and accidentally kicked them into the night. Using the light on his cell phone, he sank into a hunch and began duck-walking all over the lot in an effort to find them, Milton watching as Victor unwittingly came in his direction, his bowed head like an offering.

In contrast, I was prepared to be bored reading Kent Haruf. Years ago, a guy I had a crush on loved the hell out of his novel Plainsong. When he told me the plot, I tried to care but found that it bored the socks off my eyes. I know that’s not a real thing, but for serious, I might have fallen asleep while he explained it to me.

And yet, Haruf had me at beat drop when not-so-very-young (like legit elderly) Addie Moore, widowed and living alone, just came out with her “indecent proposal” to her neighbor and acquaintance, widower Louis Waters, and asked him if he’d agree to sleep with her nightly. I know, right?! Naturally, I was like…whaa???? Let’s. Go. The scandalous proposal only exposes our very ageist views about the courtship and sex lives of seniors. The slow burn of Addie and Louis’s relationship is life-affirming. Love and companionship may die when we lose our significant others but it can be found again, if we’re brave and bold enough to ask for it.

Our Souls at Night is spare and taut, yet reading it feels expansive and familiar. The characters eat iceberg lettuce with Thousand Island dressing. They drink root beer floats. I realized that I’d been robbed by letting a not-so-interesting man describe Haruf’s work to me—I was immediately taken in by this love after love, all the simplest pleasures that the poet Jack Gilbert tells us that we should indulge. I never imagined that I would feel so awake following Addie and Louis’s nightly confessions of the failures and triumphs of their lives. Haruf makes their conversation feel so urgent, vital, necessary, and present. They have very little to hide from each other and the tension is on the town, their adult children, and trying to process how two single elderly adults could dare to be so unapologetically casual about their relationship. They have nothing to hide from each other about who they were before and what they learned; the way they’re so honest with sharing their own stories is just so edifying. They actually make dating fun.

In some ways, Price-as-Brandt’s mundane descriptions share this style with Haruf, if you can believe it. Haruf uses a poet’s economy to make the small world of their town of Holt, Colo., palpable—the absence of excessive detail to identify place allows for such fluidity in the dialogue that you feel the characters are sitting next to you. It makes their voices so very clear. As they lay side by side talking before settling into a sleep, you hear the warmth and softness in Addie’s voice, and Louis’s small gestures become enormous, befitting a moment in a Philip Levine poem:

They lay next to each other and listened to the rain.

So life hasn’t turned out right for either of us, not the way we expected, he said.

Except it feels good now, at this moment.

Better than I have reason to believe I deserve, he said.

…

In Addie’s bedroom Louis put his hand out the window and caught the rain dripping off the eaves and came to bed and touched his wet hand on Addie’s soft cheek.

How could one make such an impossible choice given these two wildly divergent fictional universes, guys? I’m looking forward to seeing the film adaption of The Whites but for now, I choose the December-December romance in the heart of America for reminding us to risk happiness at any age, no matter what anyone thinks.

Match Commentary

By Kevin Guilfoile & John Warner

Kevin: How many of the ToB books did you read digitally this year? For me, The Whites was the only one. For some reason I feel like I should be doing it more by now, but I don’t. Which isn’t to say I don’t read on my phone—I do, every day—but it’s almost exclusively nonfiction. It’s usually texts (I have a Richard Dawkins thing in there now, one of his books, not his tweets) that I can drop in and out of while waiting for the kids at music lessons or standing in line at the butcher. I already spend too many hours each day staring at a screen, like a closet cannabis plant leaning into a grow lamp. Reading on paper is spa time for my eyes.

John: If I had my choice I would’ve read none, for two main reasons. One is that I try to keep my Amazon purchases as close to $0 as possible, and while I’m aware that there are other ways to read ebooks, my second reason is that I vastly prefer reading physical books, so I just haven’t bothered to find an alternative ebook retailer. There was a period four or five years ago where I was about 60/40 ebooks to physical books, but over time, that’s evolved to more like 5/95. The one ToB ebook I read this year was The New World, and the reasons I read it that way were because the physical copies have long disappeared from stores and I knew that it was relatively short, so the necessary screen time for reading it would be limited.

I was amused by Judge McFadden’s disclamatory introduction. Her credentials more than qualify her as a judge in our contest, particularly considering the rather broad scope of judges we’ve had in the past, but I think sometimes the reputation of our commentariat precedes us, and the judges feel obligated to do the job well or worry that their work may be found wanting.

I don’t think Judge McFadden needs to worry.

Kevin: In fact, I can add little to Judge McFadden’s analysis beyond my consent. I have always liked Price and enjoyed both of these novels, but Haruf’s book thrilled me. Reading it, I was struck by the fact that nobody (nobody I regularly read, anyway) writes about the elderly like this. In contemporary novels, older people are almost always props whose significance is only the degree to which their existence affects younger characters. Even books written by older authors—take A Spool of Blue Thread, for example—often place their elderly characters, interesting as they may be, in an orbit around the younger ones. To be fair, this might not be the fault of authors. Even very successful writers don’t always get to write the stories they’d like to.

A few years ago I had the privilege of interviewing Sara Paretsky on stage at Bouchercon, the largest of the annual mystery conventions. Sara related the difficulty she had publishing a novel that was not about her famous detective, VI Warshawski. That was astonishing to me, John. They let everyone else write novels without VI Warshawski in them. They let you and me write novels without VI Warshawski. How the hell does mystery royalty like Sara Paretsky not get to write about whatever the hell she wants? (Sara did publish that novel, by the way. It’s called Bleeding Kansas and it’s terrific.)

So some of the credit should go to Knopf for nurturing this novel into existence. It’s beautiful, it’s insightful, it’s funny, it’s wise, it’s not at all commercial. In today’s publishing environment, it seems like a little miracle it even exists, a gift to all of us from Haruf in his final days.

John: You’d think, at some point, that writers like Sara Paretsky would get a lifetime achievement dispensation to write and publish whatever they want, and yet I know a number of people who have had the critical and sales success equivalents of winning the Powerball, who tell similar stories.

Publishing is a dumb business folks. Never think otherwise.

And yet, sometimes, the fact that publishing is a business doesn’t get in the way of novelists like Kent Haruf having long and successful careers writing about quiet people in out-of-the-way places.

It’s such a slim volume, but Our Souls at Night was probably—strike that, definitely—the most emotional reading experience I had this year. This is partially because I knew that Haruf knew he was dying as he wrote it. I eased through it on a quiet Sunday morning and closed it with the most wonderful sense of melancholy coursing over me. I’d been a fan of Haruf’s earlier books set in the fictional Holt, Colo. (particularly Plainsong and Eventide), so part of me was likely mourning the fact that I’d never be invited back inside that world again.

I was worried for this little book in our tournament. Novels about the aging and lonely aren’t usually the sexiest of competitors, but to me, Haruf’s work is universal. He writes about people trying their best to love each other, and how difficult that can be sometimes. I’m thrilled that Our Souls at Night gets to stick around.

Kevin: I just checked. Do you know how many times Law & Order is on various broadcast and cable networks today? Twenty-nine times. There are literally not enough hours in the day to watch Law & Order on television. And that doesn’t even count Law & Order Criminal Intent (19 times today), and Law & Order SVU (13).

So with that in mind, a few words about The Whites. As popular as it is, one of the problems the mystery genre has had in the ToB is that by its nature genre novels can seem a little familiar. The language Judge McFadden uses in this review (old school, hardboiled, Sorkin-esque, Crimey-McCrime, noir) suggests that she’s seen these characters before. And she has. But she enjoyed Price’s novel a great deal anyway, because originality isn’t normally our only measuring stick. Crime novels often use well-known and accepted character types and settings and situations to reveal complicated truths about the darker sides of human nature. It’s difficult to feel one way or another about a transgression against a culture (or a person or a place) you know nothing about. Good crime novels often put you in a comfortable place, and then try to subvert those comfortable expectations. (There are plenty of literary novels that employ the same trick, of course.)

When someone has two novels chosen for them and has to justify their preference for one of them over another, I think originality takes on more relative significance. Yet one look at the bestseller list (or the program listings on my TiVo) and it’s clear that not many of us value originality when we are selecting what we want to read or to watch for ourselves. I’m not sure what that means, but I think it is related to Price’s initial decision to publish The Whites under a different name. We talked a little about this in our commentary last year, so I won’t repeat myself, but I hope Price’s curious, shared byline with an imaginary person doesn’t put anyone off this book.

Every year there’s a novel that’s an easy recommendation, a book you can safely put in the hands of the largest number of people and be reasonably assured they will like it. The Whites might be that title for 2016. It’s familiar, yes, but very entertaining.

Tomorrow the spotlight finds A Little Life, which might have been the most talked-about novel of 2015, if you determine that designation by tallying up the number of Style-section newspaper features written about the hip people who are reading it. A Little Life takes on The New World by Chris Adrian and Eli Horowitz. Choire Sicha will judge.

I am fairly certain The New World is the first novel with non-make-believe co-authors ever to be shortlisted for the Rooster. (I could fact check that, but it will be easier to just suffer the humiliation of a correction in the comments if I am wrong.)

The official 2016 Tournament of Books T-Shirt by book designer Janet Hansen. Order yours!