Chiraq, Drillinois

Originating on the South Side, drill music has attracted major labels to Chicago in search of young rappers—as gang violence turns the city into the murder capital. Each has everything to do with the other.

Lil Durk, the 20-year-old South Side rapper who just released his first single on Def Jam Recordings, was nearing the end of a 20-minute set at the Link Bar in Gary, Ind., when, as he put it, “a drunk woman jumped up on stage.” A member of Durk’s crew shoved her back off. This did not sit well with the crowd, which began hurling beer bottles at the rappers. Durk and his friends threw bottles back. Within moments, the club’s stage was a mess of glass shards and pooling, foaming suds. To prevent a brawl, security guards hustled the rappers offstage, ending the night’s entertainment.

The melee at the Link Bar was the fulfillment of a line in Lil Durk’s new single, “Dis Ain’t What U Want”: “I can’t do no shows / ’Cause I terrify my city.”

“There be violence at all our shows,” he admits. “We don’t control what happens in the club.”

Last October, the Congress Theater cancelled a Lil Durk show, because it feared a melee. But the violence that surrounds Durk is not just confined to clubs. Shortly after signing his contract with Def Jam, he spent three months in prison on a weapons charge. He’s a reputed affiliate of the Black Disciples street gang. And last year, he was a participant in a rap beef that ended with the shooting death of his antagonist, Joseph Coleman, an aspiring MC who went by the name Lil Jojo.

A member of rap movement called 300, a triumvirate that also includes boyhood friends Chief Keef and Lil Reese, Durk is one of the pioneers of drill music, a dark, hardcore iteration of hip-hop that originated on the South Side. Drill is a Midwestern twist on Atlanta’s trap sound, but its style and lyrics were also inspired by the gang violence that has turned Chicago into the nation’s murder capital. The term was coined by Pac Man, a rapper who was shot to death in 2010.

“It’s more of a harder sound, harder drums,” says Andrew Barber, editor of fakeshoredrive, a website that chronicles the local rap scene. “The content is more aggressive. It’s not necessarily more violent, but it’s more like Chicago’s music. It could be played alongside a Rick Ross or a Lil Wayne.”

“You’re going to give me $200,000? I’m 16. What you want me to rap about? Killing each other? Cool.”

Drill has made Chicago the nation’s rap capital—and earned it the nickname Chiraq, Drillinois, a reference to both murder and music. In the last year, a dozen Chicago rappers have been signed to major label deals—Lil Reese with Def Jam, Chief Keef with Interscope, King Louie with Epic.

But veterans of the local rap community say the labels aren’t here for the music, they’re here to exploit the city’s reputation for murder.

“The record companies want an ‘authentic urban experience,’” complains Rhymefest, a member of the generation of Chicago rappers that includes Common, Kanye West, and Lupe Fiasco, and is known for socially conscious lyrics that draws more from black poetry, politics, and philosophy than gang life. “The authentic urban experience started to represent gang banging? Guess what? In Chicago, you just had 500 murders. What you find with labels is someone who doesn’t look like the people that they’re exploiting using their image. It’s kind of like doing blackface using black people.”

To accomplish that, he says, the labels sign impressionable young rappers who are either living a thug life, or can be persuaded to present that image. “A young person’s going to say, ‘You’re going to give me $200,000? I’m 16. What you want me to rap about? Killing each other? Cool.’”

Lil Durk, whose real name is Durk Banks, is short, puckish, and graffitied with tattoos from his eyebrows to his fingers. He wears his hair cropped short, because his stylish braids were shaved off by the Illinois Department of Corrections. Durk grew up in his grandmother’s threadbare second-floor flat, whose only adornments are an overstuffed couch, a glass dining table, and a painting of praying hands above the mantel. When Durk was two years old, his father, Dontay Banks, was sentenced to life in a federal penitentiary for dealing crack.

While a student at Paul Robeson High School, Durk was introduced to producer/director DGainz, who shot a video for his song “Sneak Dissin’,” and posted it to YouTube.

“That was his first time into recording,” DGainz says. “I don’t think he was into music. He was more into street stuff.”

Operating only with a laptop computer on which he composed beats, a studio microphone to record rappers, and a handheld camera to shoot videos, DGainz helped drill break out of its South Side cradle. His YouTube page, DGaines1234, has more than 138 million views. Its most popular video is Chief Keef’s “Love Sosa,” but Durk’s “I’m a Hitta” has more than a million views, and “L’s Anthem” nearly three million. Accessible to anyone with a computer or a smartphone, YouTube allowed poor kids from Englewood to share their music without the intercession of TV networks or record labels. The early videos became hits on Chicago Public Schools students’ mobile devices.

“It’s new as far as how Chicago’s gettin’ noticed, as far as the viral world,” DGainz says. “I don’t think there ever been a spotlight on the hood. It ain’t all glitz and glamour. Everybody hearing about the violence in Chicago and they want to see what it look like.”

The “I’m a Hitta” video attracted the attention of No I.D., a Chicago native who is now executive vice president of Def Jam. No I.D. offered contracts to both Durk and Lil Reese. Last April, the two friends signed simultaneously, sitting at the same table in Los Angeles.

“I first heard from No I.D. when I made the ‘I’m a Hitta’ mixtape,” Durk recalls. “He called me, and I’m like, ‘This ain’t the real No I.D.’ And he called me, like, ‘Yeah, send me the mixtape. I want to check you out.’ But in my head, I'm like, ‘Dang, this the real No I.D.’ So I know a lot of eyes on me. Then a couple weeks later, he set up a meeting with me, and we just talked about the reason I should be on Def Jam, and I’m like, man, they signing me.”

Def Jam won’t discuss the size of the contract, but Durk says it was for “a couple hundred thousand” dollars. Shortly after signing, though, Durk spent three months in Vandalia Correctional Center for unlawful possession of a handgun. Durk says the gun belonged to a friend who was already on parole. The friend pinned possession on Durk so he wouldn’t go back to jail. The police bought that story because of his reputation as a street rapper, he claims. (According to the police report, when Durk spotted a police car, he fled through the gangway of a building, carrying a loaded, nickel-plated .40 caliber semi-automatic Smith & Wesson pistol, with the serial number scratched off. He hid the gun behind the rear wheel of a car, then ran into a house, where he was arrested.)

In Vandalia, he was a celebrity, especially after a copy of RedEye, a free Chicago tabloid featuring a story about Chicago rappers, circulated through the prison.

Jojo posted a video of himself riding past a car containing Lil Reese and an unidentified friend, shouting “you a bitch” and “I’m’a kill you.” Hours later, Jojo was shot to death near the corner of 69th Street and Princeton Avenue.

“A lot of people knew,” he boasts. “It started out during the process when they ask if you’ve got a job. I tell ’em, ‘Yeah, I’m a Def Jam recording artist.’ A lot of people like, ‘Dude, he just tryin’ to be cool. He lyin’. Until the newspaper came in. That newspaper went around the whole jail: me, Louie, Reesie. People looked like, ‘Damn, that’s him for real.’ They started believing me.”

Even though he had signed a six-figure contract, Durk was on parole, so he returned to his grandmother’s flat, which he shares with his girlfriend, Nicole Covone, and his infant son, Angelo. (Nicole’s nickname is tattooed on his wrist, Angelo’s over his eyebrow, in baby blocks.) Because he needs the parole board’s permission to leave Illinois, Durk recorded his mixtape at a studio in the South Loop, with local producer Paris Bueller.

Almost as soon as he got out, Durk became embroiled in the beef with Lil Jojo. According to Durk, his rap crew’s name, 300, comes from the movie of the same name, about a small group of Spartan warriors holding a mountain pass against the Persians. “It wasn’t a lot of ’em, but they was takin’ on everybody,” says Durk. But 300 is also a number associated with the Black Disciple Nation, signifying three stripes, one for each word in the gang’s name. Likewise, Durk says that the L in “L’s Anthem” stands for, “life, love, loyalty. You represent those three, throw ’em up,” by making the L sign with a thumb and forefinger. But it’s also the first letter of “Lamron,” the backwards spelling of Normal Avenue, where his street crew hung out. (On his Def Jam mixtape, Signed to the Streets, Durk is standing under a street sign for 64th and Normal.) Durk is also tattooed with the letters “OTF,” which stands for “One of the Family”—a Black Disciples slogan.

Lil Jojo belonged to a rival gang called Brick Squad, which is associated with the Gangster Disciples. According to Jojo’s cousin, a retired rap promoter who goes by the name Swift, the beef started when Jojo and his friends chased Durk and Lil Reese out of Adrianna’s, a suburban nightclub where the two had just performed, and posted a video of the confrontation on YouTube. Jojo also released a video called “Tied Up,” which featured a Chief Keef look-alike bound with duct tape. Jojo wanted the same success as the 300 crew, and believed that beefing with them would attract a label’s attention. But Durk participated, too. On “L’s Anthem,” he rapped, “My own niggas, I don’t trust ’em/ Brick Squad, I say fuck ’em.”

In his last diss video, Jojo pointed guns at the camera, and rapped, “Durk says fuck us so I can’t wait to catch ’im.” And he referred to 300 as “3hunnaK”—the K standing for “kill.” On the day he died, Jojo posted a video of himself riding past a car containing Lil Reese and an unidentified friend, shouting “you a bitch” and “I’m’a kill you.” Hours later, Jojo was shot to death near the corner of 69th Street and Princeton Avenue.

“Lil Jojo was trying to be famous,” says Rhymefest, who met the young rapper as a volunteer for his 2011 aldermanic campaign. “This stuff here today is about how shocking can I be? So I’m gonna go to your neighborhood, call you out, tell you I’m gonna kill you, and all this stuff, and I’m gonna post it on YouTube with an outrageous song about it. He saw Chief Keef get a deal based on that, and that was his way. He was not an extraordinary lyricist, and this was his way to say, ‘If I do this enough, I’ll get a record deal.’ And sure enough, he had labels talking with him. So that encouraged the behavior.”

Swift, who promoted concerts for last-generation rapper Twista before leaving the music business to become a private investigator, blames the music industry for his cousin’s murder.

“These kids were reaching for a false dream, and these record (companies) are coming to our city … and telling them that they’re going to be superstars,” Swift said at his cousin’s wake. “And they’re not looking at giving these kids guidance or artist development.”

In an interview at his Englewood home, Swift said he is considering filing a lawsuit against Chief Keef, Lil Reese, Lil Durk, Interscope, and Def Jam for culpability in his cousin’s death. “If the label wouldn’t have financed them, he probably would not have been dead.” He also believes the notoriety generated by the murder caused Interscope to bump up Chief Keef’s first release from a mixtape to a CD. Finally Rich sold 50,000 copies in its first week.

“Before the record label came about, you go on YouTube, we been talkin’ about guns,” Durk says. “The only thing they pressuring is they telling us to stick to what got us the deal.”

“I think the music industry is, for lack of a better word, single-handedly supplying homeland terrorism,” Swift rages. “They’re the only industry that services the ghetto. Who else searches for guys that sell drugs and talk about it, and openly pays them for it?”

Durk refuses to discuss Lil Jojo’s death—and it should be noted Durk is not a suspect, nor has he been investigated in connection with the murder. Asked whether it was fair that his name was mentioned in news accounts of the murder, Durk insists he doesn’t pay attention to newspapers, despite his earlier boast about how RedEye made him a prison celebrity.

“I don’t know,” he says. “The newspaper’s all about drama. I ain’t read none of that. I’m not too much into that.”

But Durk seems to taunt Lil Jojo on “Dis Ain’t What U Want,” which is selling for $1.29 on iTunes. “A nigga claim 300 / Add a K, you done,” he raps.

Durk does dispute that Def Jam is pressuring him to rap about violence, pointing out that violence was part of his subject matter before he was discovered—and was a reason the label signed him.

“Before the record label came about, you go on YouTube, we been talkin’ about guns,” he says. “The only thing they pressuring is they telling us to stick to what got us the deal.”

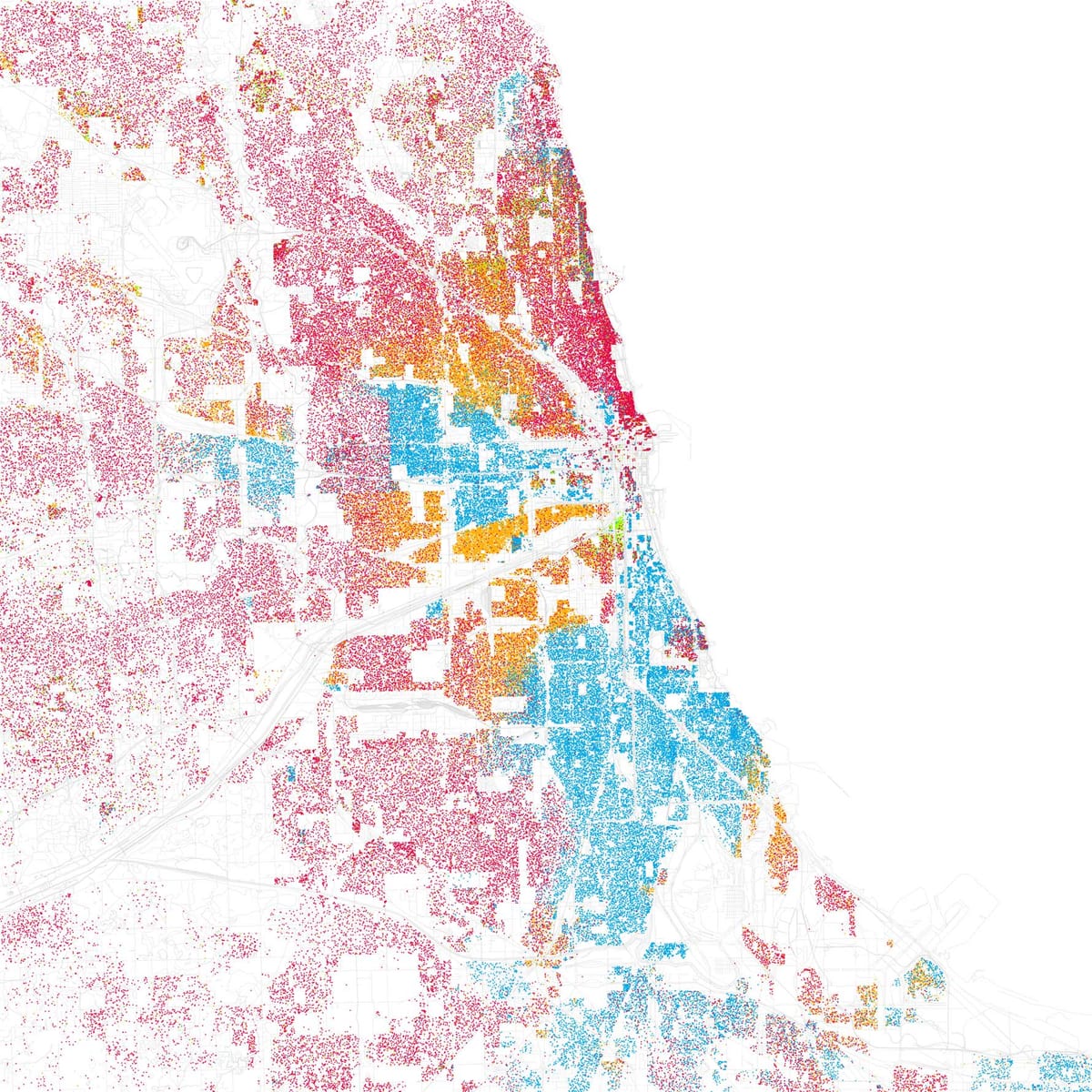

Sickamore, the Def Jam A&R man who handles Durk, says complaints about drill music come from rappers whose “voice doesn’t mean anything in Chicago.” (Rhymefest, who won a Grammy in 2004 for co-writing “Jesus Walks” with Kanye West, does not currently have a record deal.) He denies that Def Jam was attracted to Chicago because of its violence, but acknowledges the role that violence played in making the city the epicenter of rap. In common with local crime experts, Sickamore traces drill’s roots to the destruction of the Chicago Housing Authority projects, which dispersed gangbangers throughout the city, atomizing a well-organized gang structure. At one time, 500-member gangs operating out of CHA towers controlled several square miles of turf, says former police lieutenant Arthur Bilek, executive vice president of the Chicago Crime Commission. Now neighborhood gangs, like Durk’s Lamron crew, are shooting each other over the right to sell drugs on a single street corner, sending the city’s murder rate to a 10-year high.

“When the wars got really crazy, the climate of the music changed,” Sickamore says. “The music went from like OK, cool, like Kanye or Lupe … Chicago kind of reminds me of Harlem during the renaissance. I think through all the despair and the pain and the violence and all the real shit going on, I think that you get some of the most pure music, especially aggressive music. With a lot of the drill music, there’s no real separation between the street and the art in the music. They go to the studio, but they’re just as much in the mix as anyone of these kids out here, so that’s why I think the other kids see that and can relate.”

Durk hopes his rapping will take him away from Englewood. “I want to put my son in a more safer environment.” But once he leaves Englewood, can he still be Def Jam’s gangsta?

When Durk goes to the studio, he shows up at 10:30 for an all-night session, carrying a bag of BK Chicken Nuggets. He wears a red warm-up jacket and pants barely held up by a white belt that circles his upper thighs. Since Durk composes all his lyrics on his smartphone, he holds the device in his right hand while his left hand flails to the beat. He’s working on a song called “10 Year Niggas,” about friends who’ve been with him half his life. (“Same niggas from the same hood.”) Unlike other drill artists, Durk sings, his voice strained through the electronic filter of Auto-Tune. “Molly Girl,” a song off his “Life Ain’t No Joke” mixtape, is a flat-out tune. Such versatility, Durk says, will give him a longer career than if he were a mere street rapper.

“I think I can switch up any type of genre song,” he says. “If I knew about country, I can make a country song. That’s branding myself, anyway. If you stuck to one subject, and that subject run out, then you go downhill.”

There are two obstacles between Durk and enduring success. The first is simply getting people who can listen to his music for free on the internet to pay $12.99 for a CD. Chief Keef’s first-week sales of 50,000 were considered a disappointment for a much-hyped rapper with a seven-figure contract. Since CD sales are no longer the main source of a musician’s profits, Def Jam signed Durk to a “360 deal,” which also entitles the label to a share of his concert receipts and merchandising. The label will first release a mixtape, followed by a national tour and a CD in the fall. (In March, Durk performed at the Lawless Inc. showcase and the Def Jam Party at SXSW.)

The second is an issue common to all rappers, but which may be particularly acute in Durk’s case: In a genre which treats authenticity as coin, how can he continue calling himself a street rapper once he becomes a well-off recording artist? Particularly since his violent, hardscrabble background is the source of his appeal. A rapper’s success can destroy the source of that success. Durk hopes his rapping will take him away from Englewood. “I want to put my son in a more safer environment.” But once he leaves Englewood, can he still be Def Jam’s gangsta?

“That’s what people do when they make it,” he says. “Jay Z, Kanye West. Everybody had a chance to leave, they left.”

More importantly—and not just for Lil Durk, but for the entire drill music scene—what happens if the violence that inspired the music subsides? The first wave of gangsta rap grew out of the crack wars of the late 1980s and early 1990s, as chronicled on such albums as N.W.A.’s Straight Outta Compton and Ice-T’s O.G. Original Gangster. Now that Los Angeles has fewer murders than Chicago, it’s no longer the center of the hip-hop universe. If Chiraq, Drillinois, goes back to being Chicago, Illinois, the rap labels will stop sending their talent scouts to the South Side, and move on to the next desperate corner of America.