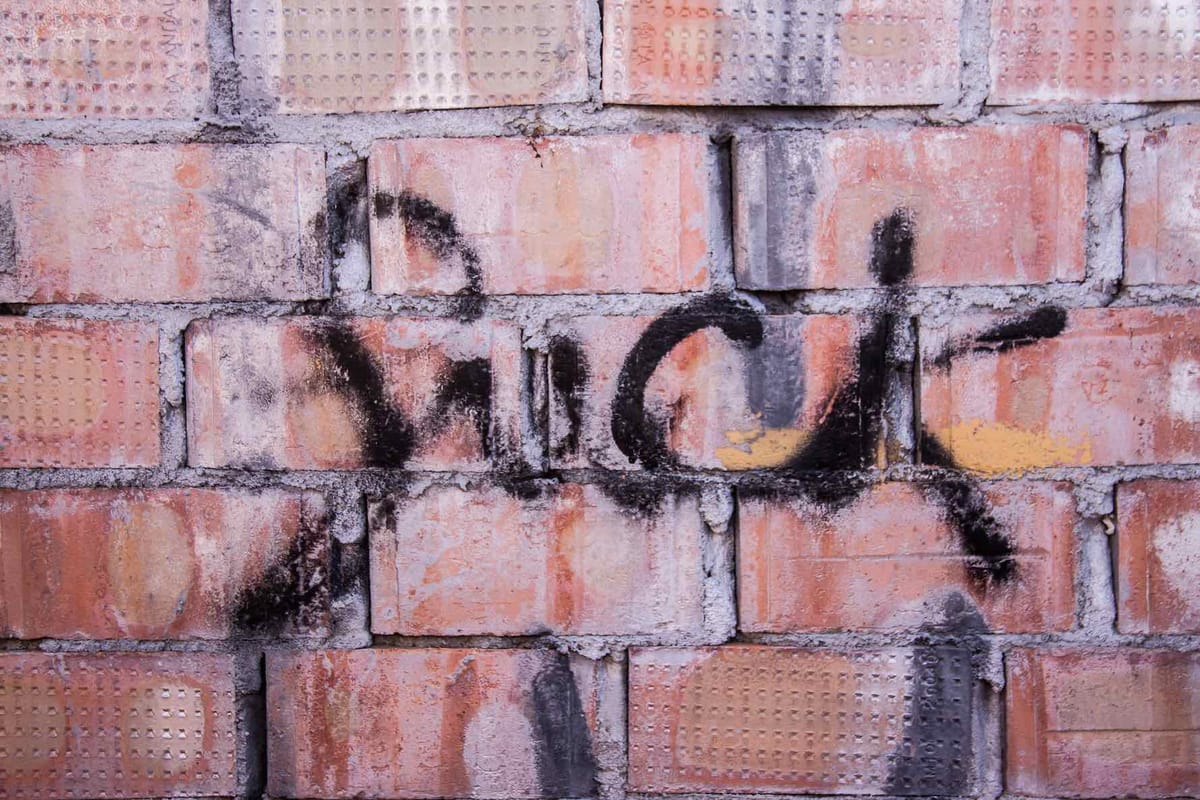

Dirty Words

Throwing f-bombs may be offensive to some people, but it's also one of the greatest mental health regimens ever devised.

The first play I ever wrote, at the age of 21, was about a woman who drank and smoked too much. (Write what you know.) The opening scene found our sauced heroine returning to her hotel room and trying in vain to light a cigarette with a childproof lighter, scourge of the mid-’90s. For drunks, igniting those tricky plastic contraptions could be like cross-stitching while wearing oven mitts, so her efforts were nothing but a series of flinty scratches. “Fuck the children!” she finally says, flinging the lighter against the wall, which always got a laugh, especially among the smokers.

It was my friend Bryan’s idea to produce a double bill of one-acts in our senior year of college. Normally I preferred locking up my artistic efforts in the file folders of my clunky old Mac, but I was trying to take more risks in those days, even if it kept me up at night, even if I had to chug a beer every time I thought about the curtain opening on an audience of strangers.

Strangers, it turned out, were not the problem. One night, my older brother came to the show. Afterward, we stood across from each other in the auditorium, two empty rows between us.

“There was a lot of cussing in that show,” he said.

“That’s true,” I said, stung by his sole assessment and trying not to let it show.

Technically, my brother was correct. The 45-minute play contained probably a dozen f-bombs, and at least one reference to the sucking of a hard male body part. But come on. This was 1996, the golden age of Tarantino and Goodfellas. Cussing was a badge of authenticity, a sign that your work was raw and vital. So many aspects of that play rattled around in my brain: Was it any good? Did it reveal too much about my own private sadness? Would the sound cues work? I had never once worried about the language.

“Have mom and dad seen this?” my brother asked.

“They came last week.”

He let out an exaggerated cry of despair, meant to make me laugh. Instead I carried this moment around for years, like a jagged stone of anger I could rub with my fingers whenever I felt the need to inflame my own sense of being misunderstood. Too much cussing. What the fuck did that mean, anyway?

Nearly two decades later, in March of 2015, I sat in a soundproof booth and recorded the audiobook for my first memoir, about the years when I drank and smoked too much. If the play had given me the ability to hide backstage, or behind an actress who was taller and prettier than me, performing the audiobook was the inverse: just me, unadorned, seated on a wooden stool with a microphone in front of me and a bottle of water at my side. The only audience I had in that tiny studio was a bearded engineer named Gary. I tried to pretend he wasn’t on the other side of the glass as I read aloud lines I had certainly written but never intended to perform. The opening scene of the book also takes place in a hotel room, strangely enough, although the episode is not a stylized fiction but an incident that took place in Paris when I was 31, where I came out of a blackout in the middle of having sex with a guy I couldn’t remember meeting. “Who are you, and why are we fucking?” is one of the early lines, and I tried to keep my voice calm and honeyed as I read it, even as I was dying inside.

It had been months since I’d looked at the book. I worried with the distance of time I would find the writing clumsy or flat. Instead I was struck by something else entirely. Midway through chapter three, which takes place during my college years, I felt some mix of irritation and exhaustion when I read this sentence: “He was one of the many male friends I never slept with, and I couldn’t tell if this was a tribute to our amazing friendship, or evidence of my supreme unfuckability.”

The words floated into my head: There is a lot of cussing in this book.

Dammit. Had my brother been right?

I was in fifth grade when I learned the thrill of teaching cuss words to my classmates. I loved scandalizing those innocents with a new and dangerous vocabulary. The discovery of dirty words was a bit like the discovery of sex itself, an induction to the shadow side. Simple children’s book words like “cock” and “pussy” were leading double lives. Vulgarity turned out to be a matter of tone, context, and tiny spelling changes. “Come” versus “cum.” “Dam” versus “damn.” Language was a spin toy I never grew tired of twirling across a wooden floor.

The dirty words arrived from various sources. My older cousins were a reliable supplier of R-rated comedies starring Eddie Murphy, Bill Murray, Steve Martin. The Breakfast Club came out my fifth-grade year and beefed up my playbook. I prided myself on reading beyond my age range: Stephen King, John Irving, V.C. Andrews. And of course there was Top 40 radio. I was 11 when Tipper Gore, wife of then-Sen. Al Gore, launched a nationwide campaign against filth in pop songs, which was pretty much a checklist of my favorite artists: Prince, Madonna, Cyndi Lauper, Mötley Crüe. It seemed to me, even then, the only art that mattered was the art that contained questionable language, double entendre, “adult situations.” Was something in poor taste? Then you could find my name in bubbly letters on the waiting list.

Cussing was also an adult privilege. I was the youngest in a large brood of cousins, and some of my earliest memories involve being teased for my softness, my clinginess. I was a sensitive kid, who over-identified with her stuffed animals. By the time I’d reached double digits, I was ready to leave the vulnerability of childhood behind. Dirty words were a way to brine the tender pink baby skin so that it became thicker, coarser, calloused. Cussing made you tough.

Fifth grade happens to be the year I got busted for cussing. A group of us had a habit of passing notes behind the teacher’s back and hiding them in our desks, a stash eventually discovered, although mine were the standouts: I called the teacher a bitch. I used words like “bullshit.” After class, I slouched in my plastic seat as the teacher chided us, and each of us was sent home with an uncomfortable letter for our parents.

I was a sensitive kid, who over-identified with her stuffed animals. Dirty words were a way to brine the tender pink baby skin so that it became thicker, coarser, calloused.

“Help me understand why you’re so angry,” my mom said when she came into my room that night. My mother was training to be a therapist. She saw in my notes a simmering rage I had masked in our polite interactions, and I told her I wasn’t angry, because I longed to be a good kid, a sweetheart, a straight-A student. I did not understand that sweethearts still felt anger, too, and that “anger” was exactly the word to describe the burning I felt.

I was angry I had been born into a family of earthy, middle-class eggheads, then drop-kicked into a rich school district where tony labels and status cars determined your value. I was angry that my underwear clotted with blood each month, even though, to my knowledge, no other girl had gotten her period and I was the youngest kid in the class. I was angry that my mother spent all her time with other children instead of her own, that my father was silent and unknowable, that my brother preferred football practice and computer games to the company of his younger sister, and that for years I had been forced to stay with the librarian after school, watching the same boring filmstrips over and over until one of the older neighbor kids got out of class and could walk me home. I was angry because I was weird and wrong-sized and alone, but in fifth grade, you can’t get your hands around those feelings. You just have “shit,” “bitch,” “motherfucker,” “goddammit.”

By middle school, my mother was fighting me on so many fronts. The amount of television I watched. The kind of food I ate. My commitment to Sun-In, electric blue mascara, and Clinique foundation in unnatural shades of tan. However, she did not fight me on cussing, and I am grateful for this. It was a soft sin, so much superior to fists and punched walls. She understood the pressure-valve release of those bleep-able words. Cussing may be objectionable to some, but it is also one of the greatest mental health regimens ever invented. The gratification of a dramatically drawn-out “f,” the grand, percussive “k” at the end. Use in case of emergency.

Having just written a book about my drinking, it strikes me how much the appeal of cussing tracks with the lure of alcohol. They are both a salve for uncomfortable feelings, a grown-up thrill, an expression of freedom. By college, alcohol and cussing were twin emblems of liberation. Fuck this, let’s drink. In those years, my heroes were men who cussed up a blue streak. I’d been weaned on the macho banter of David Mamet, the gutter growl of Tom Waits, the raunchy philosophical riffs of Tom Robbins. When I wrote that play in my senior year, I was trying to capture the same dirty poetry of the streets—never mind that I had grown up on the tree-lined streets of upscale suburban Dallas. I was also trying to camouflage my own girlishness. That play had been inspired by a break-up, and though failed romance is one of the great artistic drivers, I still felt a stinging shame for its drippy emotional center. So I carpet-bombed each scene with cigarettes and empty liquor bottles and f-bombs to detract from my own heartbreak. Come to think of it, I did the same thing in real life, too.

When my brother dinged me for the play’s language that evening in the auditorium, I was disappointed, but not surprised. By 1996, he and I were standing on two different sides of the yawning culture wars. He was a naval officer, a Civil War history buff, who preferred Tolkien books to postmodern fiction and wore Polo shirts and baseball caps for about 20 years straight. My brother is not a political conservative so much as a philosophical traditionalist. His attitude about women struck me as particularly old-fashioned. Years after that exchange, he would say of Sarah Silverman, “She’s so pretty. Why does she have to say such filthy things?”

And at least one answer to that question is: “Because guys like you say things like that.” Sarah Silverman did not chew the broken glass of endless open mic nights, wasted audiences, and obnoxious hecklers in order to be told she was “pretty.” And one of the ways she proved herself in that swinging-dick arena was to be just as gross, just as outrageous, just as cringingly vulgar as the many, many male comics who took the mic before and after her. I felt the same impulse in my own writing. To be a foul-mouthed woman was to smash the bell jar. To burn the corset and light your cigarette against its lapping flames.

You see a similar moxie in online feminism, where cussing has long been a tribal marking for a new wave of activists who take pride in their refusal to sound like proper ladies. “Shit is fucked up when it comes to appearances and women,” reads a typical line from Full Frontal Feminism, a 2007 book by Jessica Valenti, founder of Feministing and one of the most influential figures in today’s feminist movement. Cussing signals defiance, swagger, exasperation, but also humor, which upends the “prude” and “scold” label all too easily thrown at women speaking truth to power. Feministing has a regular “Friday Feminist Fuck Yeah.” Two recent headlines on Jezebel read, “Why the fuck are middle-class parents this overwhelmed?” and “Wow, what the FUCK is a ‘babyccino’?”

But singling out feminists for cussing on the internet is a bit like pointing out that swimmers get wet. The internet is an ocean of f-bombs, and I say that with love. This is the realm of dick pics, nude selfies, crass clickability. So ubiquitous and necessary is the word “fuck” in the kneejerk wired world that cutesy acronyms and abbreviations were invented: Eff this, WTF, LMFAO.

Good writing is purposeful, rigorous, careful. My cussing had become the opposite.

One reason why my writing probably remained blue during my late twenties and thirties was that it stayed primarily online. Daily newspapers keep strict standards for language, but I came up in the alternative newspaper world, where cussing was nearly mandatory. And then I transferred to the world of blogs and websites, where editors rarely pushed back on my copious swearing. (Apparently having no advertising model or paying customers means you can’t piss them off.)

Back in the ’70s and ’80s, television limited the language used in widely available entertainment. George Carlin’s famous seven dirty words routine is centered around things you can’t say on network TV, which prompts the obvious question: What’s “network?” Entertainment has splintered so dramatically, and the internet is still untamed country, free of government regulation. In the pilot of Aziz Ansari’s wildly lauded Amazon show, Master of None, he says to a little girl he’s babysitting, “Let’s get the fuck out of here.” It’s meant to be a comic sign of his ineptitude as an authority figure, but swearing in front of the kids is also a commentary on the day. The internet is a place where anonymous posters can fire off death and rape threats, and ISIS posts propaganda to recruit new members. Nobody is raising an eyebrow about your “bitch” and “shit.”

I suppose the life cycle of a four-letter-word fanatic would be that eventually you have kids, and the wee ones act as bumpers on your language. I haven’t had kids, though, and I’m not sure I ever will. My friends have children old enough to read my work, and during the lead-up to my book’s release, a few kids asked if they could have a copy. No. Oh, nooooo. Disappointed, they sometimes asked if anything else I had written would be kid-friendly. Surely I could find something, right?

I once wrote a piece about training my cat Bubba to walk on a leash. Now here was something for the wee ones: misadventures with my cute, cuddly, orange tabby. I opened the article, however, to discover this sentence: “Lately Bubba has been a real dick.” Even in a story about my cat, I couldn’t help cussing. I paged through piece after piece in my archives. To my dismay, I could not find one I liked in which I didn’t say something racy, questionable, or flat-out profane. It’s like I didn’t trust my own storytelling. I had to keep calling attention to my bohemian nature: Hey, look, you guys, I’m down.

No one has ever complained about my language, at least to my face. Well, I did get one negative response. A few months after my book came out, someone posted a note to my author’s page on Facebook, which read something like, “Do you know that when you use the lord’s name in vain, it’s like slapping a person of faith in the face?” On one hand: Jesus Christ. On the other hand: Was there something to her comment? There are many other words I have eliminated from my vocabulary because they might potentially offend someone, even if that was never my intent. I’m not saying I’ll never use “oh god” again. I’m saying when I do, I should think about whether it’s necessary. Good writing is purposeful, rigorous, careful, but my cussing had become the opposite.

Recently, I had dinner with my brother. We get along better now and have dinner every month or so at a sushi restaurant where we make fun of the excessive blue ambient lighting. That’s Dallas in a nutshell: always working overtime to look fancy.

“So I’m writing a story about cussing,” I say, as we dig into an ahi tuna tower that’s been smashed on the plate by a carefully manicured waitress.

“That’s a good subject,” he says.

I ask if he remembers what he said after seeing my play in college. He cringes and nods. “That never should have been the first thing out of my mouth,” he says. I want to know, though, why had it bothered him so much? Was it because I was his younger sister? Was it because I was a girl?

“Definitely a younger sister component,” he says. “But I also think I didn’t understand why you wanted to be that way. You have to remember, I had grown up in these male-dominated structures, and I didn’t understand. Why didn’t you just want to be this dainty, pretty girl?”

I get it. I wanted that, too, for a while, except life had given me outsized emotions and last year’s jeans and the lonely pain of squares among circles. For a long time, I didn’t have a way to express this, but life had also given me an ability to bend the chaos of my emotions and pin them on a page. It helped to have cuss words. It helped to have alcohol, too, at least until I had to give it up. I’m not sure I ever needed either of them, but they gave me an assist on the long, uncertain path of a creative career, one that paid the bills in three different cities and resulted in hundreds of published stories and at least one book, which is not bad at all.

People often ask how I feel about strangers knowing my secrets, but I rarely worry about them. I worry about the people who know me best, the ones I love.

Last July, a few days after my brother finally read my book, we’d gone for dinner at that same sushi restaurant. My parents had seen the manuscript months before it came out, but my brother had insisted on waiting for the hardback. My hands trembled as I put on my makeup that night. What would he say? Had I embarrassed him again? People often ask how I feel about strangers knowing my secrets, but I rarely worry about them. I worry about the people who know me best, the ones I love. I worry about failing them.

“Your book was great,” my brother told me after we got seated. “I loved it.” I waited for the “but” to come, and it never did.

One of the tricky things of adulthood is that you become responsible for your own behavior. It’s not on your parents, or your kids, or your friends to micromanage your behavior—it’s on you. We live in a world of innumerable choices. I could eat all the ice cream in the freezer. I could sit in bed all day watching Shark Tank. I could cuss in every story I write. Free country, motherfucker. But in the end, do those choices reflect the person I want to be? Foul-mouthed, mouth crammed with Häagen-Dazs peanut butter and chocolate, and talking back to Mark Cuban? And the answer is, on occasion, yes. But not always.

I don’t know that there’s too much cussing in my book. I did a search for “fuck” in my manuscript and counted 48 uses. By contrast, The Liar’s Club, written by the famously foul-mouthed Mary Karr, has a perfectly restrained eight. My book is an honest and accurate reflection of who I was in my twenties and thirties, when I was punching so fast and so hard. What’s funny about the idea of cussing as authenticity is that cussing is a posture. When we say cussing is real, what we mean is that people do talk that way. But cussing is not necessarily an authentic way to speak. For the tough guys in Goodfellas, the cuss words are a put-on, a slick suit they wear to sound a certain way, the same way their defensive homophobia is, in part, a deflection against anyone thinking they’re soft.

My reliance on cursing, like my dependence on drinking, was in part a desire to be more than what I am: a sensitive person who thinks too much about herself and other people. Of course, cussing is also the cherished domain of the passionate, the enthusiasts, the people who need extra exclamation marks, and I am proud to be among their ranks. Don’t get me wrong: I’m not swearing off cuss words. No, no, fuck no. But I also know that if you don’t pay attention, so much uncompromising language will start to compromise your own voice.