Dressed to Kill

Real-life villains to inspire costumes, including the conquistador so horrible the king of Spain made it a crime to say his name.

Lope de Aguirre (c. 1511-1561)

As one historian said of Aguirre, no one who knew the man ever said a good word about him. Even Aguirre called himself “The Wanderer,” “Traitor,” and “The Wrath of God.”

The younger son of a middling family in the Basque region of Spain, Aguirre came to the New World in 1534 to seek his fortune. The chroniclers in Peru were unanimous in describing his small stature, ugly face, lamed leg, beady eyes, thunderous voice, and constant stream of obscenities.

After discovering the fabled colonial wealth was controlled by the nobles, the Church, and royal bureaucrats, Aguirre spent 25 years breaking horses, working as a mercenary, and getting in trouble with the law. Along the way he sired a half-native daughter named Elvira, upon whom he doted, and who was “not at all bad-looking,” according to a chronicler.

Peru was filled with hard-bitten drifters like Aguirre, malcontents capable of any mischief. Hoping to clean up the colony, the viceroy decided to send a large expedition down the Amazon in search of El Dorado, the legendary city of fabulous wealth, figuring the undesirables would resettle elsewhere or simply perish in the jungle.

The commander of the expedition was Pedro de Ursúa, a handsome young nobleman named governor of El Dorado before it had even been found; that was his first and last triumph.

In September 1560, half of Ursúa’s brigantines sank the moment they hit the river. Instead of delaying the journey, Ursúa decided to save space on his remaining ships by abandoning most of his food supplies. Around 300 Spaniards, including Aguirre and the adolescent Elvira, and around 600 Indian slaves set sail, hoping to forage from one of the least hospitable landscapes on earth.

Ursúa made another poor decision when he brought along his mistress, the Doña Inez de Atienza. Reputedly the most beautiful woman in Peru, Lady Inez was rumored to be a sorceress who had unmanned Ursúa with lascivious witchcraft.

Believing Ursúa was leading them to extinction, Aguirre recruited a gang of cutthroat supporters. On New Year’s Day 1561, the mutineers cut down the governor of El Dorado.

Afterward, the group composed a rationale for why they had mutinied and began signing it. But Aguirre stunned everyone by boldly writing “Traitor” next to his name.

Aguirre explained that it was time to face facts: The mutineers would be considered criminals no matter what justifications they wrote. He also declared that El Dorado was a myth and the search should be abandoned. Instead, Aguirre advocated, they should sail back to Peru, rally other hard-luck cases like themselves, and take control of the country.

This was the first of several remarkable speeches and letters by Aguirre that rank among the earliest declarations of American independence. Unfortunately, the traitor’s revolution degenerated into a reign of terror.

“Does God think that because it rains in torrents I shall not return to Peru and destroy the world? If so, He is mistaken in me.”

The stress took its toll: Aguirre lost his mind, rarely sleeping, always wearing full armor, and killing on a whim. Cursed from the start, the expedition became consumed by murder, suspicion, and fear. The brutal execution of Doña Inez added to the horror: Aguirre’s henchmen “enjoyed the slaughter and prolonged the agony,” stabbing the lady repeatedly until “even the most hardened men in the camp, at the sight of the mangled victim, were broken-hearted.”

The survivors eventually reached the ocean but not before Aguirre abandoned their starving slaves in a wasteland populated by cannibal tribes. On the small island of Margarita, off the coast of what is now Venezuela, they terrorized the population and drank themselves into a stupor. Then, blocked from moving through the sea by watchful colonial troops, Aguirre returned to the mainland, burned his boats and started marching south to Peru. The desertion rate climbed, and when the weather turned against him as well, he swore, “Does God think that because it rains in torrents I shall not return to Peru and destroy the world? If so, He is mistaken in me.”

Run to ground in a small town, Aguirre’s army melted away. But the Wrath of God had one last outrage to commit; knowing his revolt was finished and with it his daughter’s respectability, Aguirre refused to let Elvira become a “mere mattress for the unworthy” as some soldier’s spoil of war. Elvira begged to be spared but he stabbed her to death, sobbing, “My daughter, my daughter!” Finally, spent, he tossed away his weapons and lay down on a bed, waiting for the inevitable.

When the troops arrived, an unresisting Aguirre was stripped of his armor and shot. The blast only wounded him, and Aguirre spat, “That was nothing.” After a second shot he gasped, “That will do,” and fell dead. The traitor’s head was displayed in an iron cage, along with Elvira’s bloodstained bodice, but his ghost remained free. Even today, flares of gas in the nearby swamplands are said to be the traitor’s spirit, damned forever to wander the subtropical landscape.

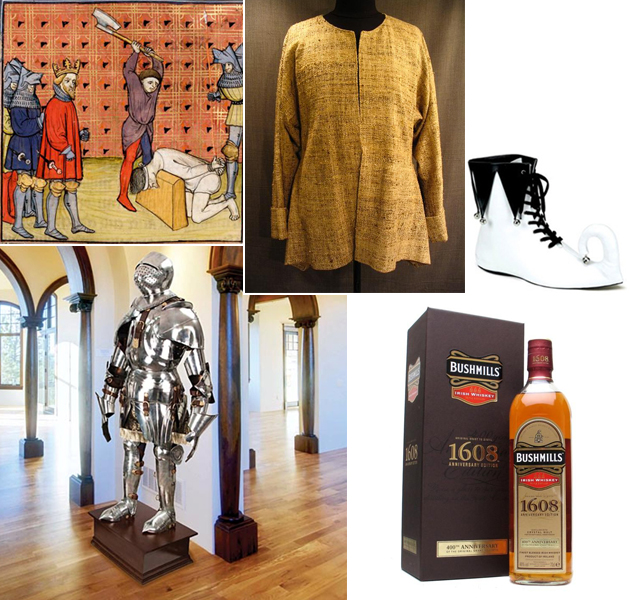

Charles the Bad (1332-1387)

Formally titled King Charles II of Navarre, Charles the Bad was summed up best by historian Barbara Tuchman: “He was volatile, intelligent, charming, violent, cunning as a fox, ambitious as Lucifer…His only constancy was hate.”

Navarre’s birthright was also his curse. A direct descendent of the deceased King Louis X, Navarre had better claim to the French throne than the reigning monarchs, his cousins the Valois. Believing he’d been cheated of the French crown, though he was king of a small Pyrenees monarchy and lord of extensive estates in Normandy, Navarre seethed with resentment. He announced his grudge in 1354 with an audacious murder. His target was the constable of France, Charles d’Espagne, an unappealing striver who’d become a favorite of French King Jean II. Jean heaped d’Espagne with rewards, including some of Navarre’s lands, and Navarre realized he could wound the Valois and eliminate a rival in one fell swoop.

While Navarre waited in the woods, his brother and other assassins crept into the sleeping constable’s room. Awakened, D’Espagne fell to his knees, pleading that he’d give back the land and anything else Navarre wanted. But the brother “villainously and abominably” attacked d’Espagne, the others joined in, and d’Espagne died, his corpse mangled with more than 80 wounds.

Utterly shameless, Navarre bragged about the murder in a letter to the pope, “God knows it was I who with the help of God had Charles d’Espagne killed.” But Navarre’s brazenness was matched by his wits; he knew that many loathed the favorite as much as he did, and he figured, correctly, that he’d get away with the assassination.

The Hundred Years War between France and England was at its height, offering innumerable opportunities for intrigue, but the situation changed after the Battle of Poitiers in 1356, when Jean II was routed and captured by the English.

With the French economy in tatters, the nobility disgraced by Poitiers, and bandit armies plundering the countryside, the peasants revolted in 1358. Paris was seized and peasants ran amok in the surrounding areas. Navarre’s duplicity helped turn the tide when, for once fighting briefly on behalf of the Valois, he invited a peasant leader named Cale for a parley under truce. A naïve Cale believed the laws of chivalry applied to him as much as any man, but Navarre imprisoned him, then rode out and massacred the stunned peasants. Afterwards he celebrated by crowning Cale with a red-hot circle of iron and beheading him.

Only 56 but aged beyond his years, he was wrapped in brandy-soaked bandages every night to ward off chills.

Navarre continued to battle the Valois any way he could, whether collaborating with English invaders, dosing the dauphin with arsenic, or making a brief alliance with the Paris mob during an attempted coup. He also found time to poison a cardinal and a mercenary warlord, as well as to turn the glittering count of Foix against his heir, ruining the mightiest family in southern France. It was clear there would never be peace until Navarre was suppressed, and in 1364 King Charles V openly declared war on Navarre. It took many years, but one by one Navarre’s strongholds were reduced until, in 1378, his political destruction was complete and he was pent up in his impoverished mountain kingdom.

Navarre’s death in 1387 was as grotesque as his life. Only 56 but aged beyond his years, he was wrapped in brandy-soaked bandages every night to ward off chills, with the shroud-like linens actually sewn together so they would stay in place. Navarre ordered that no one could approach with an open flame, but one winter evening when he was being sewn up a servant grabbed a candle to burn off a pesky thread. The shrieking Navarre was instantly bound in flames and lingered in agony for weeks before giving up the ghost. The story of his macabre death was a sensation throughout Europe, everyone agreeing that if any man got what they deserved, Charles the Bad was he.

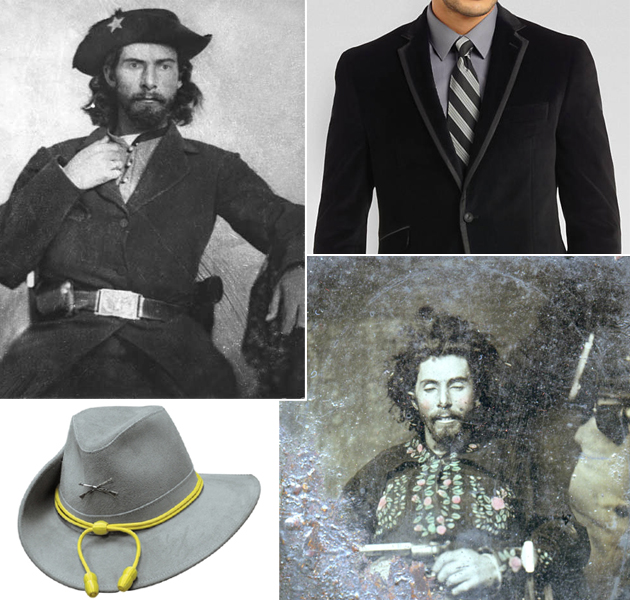

Bloody Bill Anderson (c. 1839-1864)

While Jesse James continues to be a pop culture icon, his mentor “Bloody” Bill Anderson goes overlooked. This is a shame, because Anderson is perfect for Hollywood: a handsome, young sociopath with an amazing head of hair.

The Anderson family first made its name in the late 1850s along the Kansas-Missouri border. Bill and a younger brother were horse thieves; another brother murdered an Indian; their father was shot down while attacking a judge; and in 1860 their mother was struck dead by lightning, perhaps to stop her from making more Andersons.

Bill would have remained a petty criminal except for the Civil War. The conflict along the Kansas-Missouri border was unrivaled for bitterness, with pro-Confederate nightriders executing Unionist neighbors and loyalist militias plundering Southern sympathizers. Anderson was a typical guerrilla, robbing and smuggling, occasionally shooting at Union soldiers, and using the war as cover for personal vendettas.

Everything changed in 1863, when federal authorities sent Anderson’s three younger sisters to Kansas City in an effort to eliminate the guerrillas’ support network. The girls were jailed in a residential building but modifications by federal guards accidentally destabilized it and the building collapsed, leaving one of the girls dead, another crippled for life, and the third seriously injured.

Believing the building collapse was deliberate, Bill and the guerrillas went berserk and descended en masse on Lawrence, Kan., an abolitionist stronghold, where they massacred nearly the entire male population, including children. Anderson led the way, personally killing 14 of the approximately 200 victims and telling a Lawrence woman, “I’m here for vengeance and I have found it.”

His revenge had only begun. Anderson spent the winter in Texas, then returned to Missouri the following spring and terrorized the state. With Frank and Jesse James, Bill tortured Unionists, robbed banks, and bombarded passing steam ships for fun. With his trademark Union scalps adorning his saddle bags and gaudy ribbons tied around his hat, Anderson appalled even veteran Confederate officers with his barbarism.

Bill upped the ante in late September with a train robbery in the small town of Centralia. Holding up trains was unusual at the time, and the James brothers undoubtedly took notes when Anderson blocked the tracks, then looted the civilian passengers. There were also 24 unarmed Union soldiers on the train, most of them on furlough, and Anderson ordered them to line up and strip. After pulling one man aside as a captive, Anderson had the defenseless men executed, telling them, “You all are to be killed and sent to hell.”

After pulling one man aside as a captive, Anderson had the defenseless men executed, telling them, “You all are to be killed and sent to hell.”

Bill’s wasn’t finished, and that afternoon he ambushed the federal troops that had been following him. The guerrillas went wild, cutting off noses and genitals along with scalps.

Anderson was the most hunted man in Missouri but that didn’t make him anxious. In late October, he was spotted bowing in the mirror. “Good morning, Captain Anderson,” he greeted himself, “How are you this morning?” “Damn well, thank you,” he replied.

Bill’s situation took a turn just the next day, when he was lured into a federal trap. Though outnumbered, Anderson could have made a run for it. Instead, Bloody Bill put the spurs to his horse and charged the Union line, pistols blazing. Accompanied by only one other rider, he seemed as if he could have been carried through the line by sheer hate, but the moment ended in a storm of bullets. Except for several strange photos of his corpse, Bloody Bill was no more.

Jeronimus Cornelisz (1598-1629)

Most people associate the Dutch with happy things, such as windmills, tulips, and drugs. But only the latter applied to the apothecary Jeronimus Cornelisz, and even his murky profession pales in comparison to the mass murder he inspired on a few tiny islands off the coast of Australia.

The son of an apothecary, Jeronimus grew up in Frisia, a northern province of the Netherlands. Cornelisz’s parents were Anabaptists, but nothing seemed too unusual about Cornelisz’s beliefs when he took up his father’s mortar and pestle and moved to the thriving city of Haarlem in 1627.

There he prospered, setting a stuffed crocodile above his pharmacy counter as a trademark, and living above the shop with his young wife. He also made some dubious friends, freethinkers of the wildest beliefs, namely that individuals who had brought God into their hearts were incapable of sin no matter what acts they committed. One of these libertines, the painter Torrentius, was arrested and tortured by the Calvinist authorities, who put the town executioner on the case. But Jeronimus had plenty of other worries.

His wife had died of infection shortly after delivering their first child with assistance from a deranged old midwife, who admitted that she suffered “torments inside her head.” Clearly lacking an eye for reliable help, the new father chose a notorious slut to nurse the infant. Within a few months the child died of syphilis; the case created a scandal when Jeronimus brought it to court, as some blamed the disease on his dead wife, not the wet nurse.

With his wife and son dead, his business ruined, and himself possibly a person of interest to Haarlem’s hangman, Jeronimus surrendered his shop to creditors in October 1628, and fled to Amsterdam. There he signed on with the Dutch East India Company, the traditional last resort for the otherwise unemployable. The company was desperate for men of learning and immediately gave Jeronimus a position as deputy agent aboard the Batavia, a trade ship bound for the Spice Islands in Indonesia.

The voyage was a nightmare. The alcoholic captain quarreled with the company’s top representative, named Pelsaert; many of the crew, led by the pharmacist, became mutinous; and an ugly competition broke out over an unusually attractive woman passenger. The mutineers were about to make their move when, in June 1629, the Batavia slammed into a coral reef near a tiny cluster of islands called the Abrolhos about 80 miles off the barren coast of Australia.

The captain, Pelsaert, and other senior crew soon set off in a longboat to seek help from Java, leaving the apothecary in charge of the 200 shipwrecked passengers. About 160 of them were huddled on an open, waterless island they named Batavia’s Graveyard. Jeronimus sent another 40 or so, namely a soldier named Hayes plus others who might be troublemakers, to investigate nearby islets that Jeronimus believed were also devoid of water.

Jeronimus soon became a cult-like figure, commanding the island from a central tent, wherein were kept all the weapons, food, and supplies they’d scavenged from the shipwreck. Surviving on rainwater and strictly rationed food, the pharmacist quickly decided that he had too many mouths to feed and something had to be done about the Graveyard’s surplus population.

One young henchman became so frenzied that he ran around shouting, “Who wants to be stabbed to death? I can do that very beautifully!”

The murders were simple and brutal. The apothecary, preaching that he could do no sin, merely named a family or individual and his henchmen cut them down with swords, pikes, axes, and mauls, eventually leaving over 110 corpses hurled into mass burial pits. Others were drowned or strangled, with the women set aside for the mutineers’ pleasure. With murders occurring almost daily, one young henchman became so frenzied that he ran around shouting, “Who wants to be stabbed to death? I can do that very beautifully!”

Jeronimus avoided killing anyone with his own hands, though he did prepare one dose of poison in case it was needed. Instead he gloried in his newfound godhead, controlling his thugs with flowery words, dressing absurdly in fine coats and trinkets, and forcing the attractive female passenger to become his concubine. His sick fantasy could only extend so far, however, and by late August several things became clear: The mutineers were running out of food and water, and the men he’d sent to die on other islands weren’t dying at all but were thriving.

Hayes and his people were fortunate; not only had they discovered an island with several fresh wells, but birds, fish, and small wallabies were plentiful. Also in Hayes’s favor: Several escapees from the Graveyard had informed him of Cornelisz’s reign of horror. Calling themselves “The Defenders,” Hayes and his men had a line of watchmen and handmade weapons prepared for when mutineers attacked.

Jeronimus tried to smooth-talk his way into ambushing the Defenders. Proclaiming his friendship, he offered a truce in which his mutineers would exchange wine and cloth for food and water. The pharmacist and his men milled around the beach at Hayes’s island, waiting for a chance to attack. But the Defenders leapt first, and the pharmacist’s henchmen were seized and killed. Jeronimus himself was tied up, thrown into a rocky hole, and forced to pluck birds, given a raw one to eat out of every nine he cleaned.

When Pelsaert and a rescue ship arrived, Cornelisz tried to doubletalk his way through a trial, but, eventually broken by water torture, he confessed and was sentenced to have both hands chopped off before being hung, the worst punishment in the Dutch books.

The apothecary had one last trick up his sleeve, and promising that “God will perform unto me this night a miracle, so that I shall not be hanged,” he swallowed his own poison. His concoction was a failure, however, merely tormenting him with digestive issues, and Pelsaert commented snidely that, “his so-called miracle was working from below as well as above.”

Hands lopped off, Jeronimus stood on the gallows screaming at the equally angry crowd. Insisting he’d get a fair trial in the afterlife, he met the noose shrieking, “Revenge! Revenge!” The onlookers were then sickened by his extended death throes, but not enough for them to grab the swinging legs and help the man toward his much-desired audience before God.

Sadie the Goat, Gallus Mag & Other Denizens of Satan’s Circus (late 1800s)

Although the red-light district called Satan’s Circus only encompassed a 20-block area of Manhattan, the moniker could have represented all of New York’s villainous wards. The Bowery, Five Points, and the waterfront all had their infernal charms, including brothels, gambling hells, opium dens, drinking dives, or perverse dancehalls that combined a bit of everything. The cast of scoundrels and hussies haunting these districts formed a cavalcade of sins, all of them worthy of costumed emulation.

Among the most colorful characters along the 1870s waterfront was a female gang leader called Sadie the Goat. She got her nickname by headbutting victims in the stomach and mugging them. Sadie the Goat ran her gang in style, even stealing a boat one summer and flying the Jolly Roger on its mast. The Goat and her crew sailed up and down the Hudson River, killing and looting their way through riverside hamlets, but Sadie was finally forced to return to New York when farmers began shooting at the sloop on sight.

The Goat was positively kittenish, though, compared to the roughest woman in New York, Gallus Mag. A six-foot tall Englishwoman, Mag ran a Water Street dive with pistols jammed in her skirt and a truncheon strapped to her hand. Because beating up wharf rats wasn’t enough for Gallus Mag, she often chewed or cut off a victim’s ear and then plopped it into a pickling jar. One of those pickled ears once belonged to Sadie the Goat, but Sadie got back in Mag’s good graces by bringing her a share of her pirated spoils. Honored by the gesture, Mag dipped into the jar and returned Sadie’s ear. The Goat was so pleased that she had the ear placed in a locket that she wore around her neck.

Mag and Sadie weren’t the only satanic ladies running around New York. A procuress called Jane the Grabber specialized in abducting the daughters of well-off families and turning them into prostitutes. And if Jane happened to grab any nice jewelry along the way, she could sell it via Marm Mandelbaum, for two decades the city’s leading fence. Marm ran a veritable criminal empire out of her haberdashery, passing along millions of dollars of stolen goods. When the district attorney finally nabbed her in 1884, she jumped bail and absconded to Canada, sticking the bondsman with a fraudulent property title.

A procuress called Jane the Grabber specialized in abducting the daughters of well-off families and turning them into prostitutes.

As vile as these women were, the gents were just as bad, such as a vampire named George Leese, aka “Snatchem.” Snatchem was not a handsome man; a journalist described him as “a beastly, obscene ruffian, with bulging, bulbous, watery-blue eyes, bloated face and coarse swaggering gait.” When he wasn’t working as part of the Slaughter House Gang, Snatchem moonlighted as a leech at bareknuckle prizefights. There he would clean the boxers’ wounds by lapping up their blood between rounds. He had few regrets about his chosen professions, proudly describing himself as a “kicking-in-the-head-knife-in-a-dark-room fellow.”

At least Snatchem was paid for his vampirism, unlike a Bowery freak called Ludwig the Bloodsucker. A dumpy German with an oversized head and nasty thatches of hair sprouting from both ears and the end of his nose, Ludwig apparently drank body fluid just for fun. Where these beverages came from isn’t mentioned, though it appears that whatever shortages the Bowery may have experienced from time to time, human blood wasn’t among them.

Thankfully for those who couldn’t stand another day of guzzling blood, the Bowery dive McGurk’s Suicide Hall offered a fatal rest from their labors. The low-rent establishment got its name after a couple of aging hookers, Blond Madge and her partner Big Mame, decided to end it all by drinking carbolic acid. Madge died on the spot, though poor Mame spilled most of hers, ending up alive but so hideously disfigured that she was banned from the bar. Madge and Mame started a craze, and in 1899 alone six people killed themselves at McGurk’s. Considering the staff at Suicide Hall, it’s a wonder more clientele didn’t top themselves. The headwaiter, Short Change Charley, kept a bottle of knockout drops ready in case he wanted to mug someone completely instead of just bilking them of their coins. The bouncer, “Eat-Em-Up” Jack McManus, was a brute capable of beating up four drunks at a time. Eat-Em-Up eventually met his match, though, and died with a lead pipe literally wrapped around his head. And through it all, the owner, John McGurk, shamelessly profited from the bar’s reputation, making the place into a morbid tourist attraction.

For those wishing to learn more about these wicked lives and times, suggested readings include Stephen Minta’s Aguirre, Barbara Tuchman’s A Distant Mirror, Albert Castel and Thomas Goodrich’s Bloody Bill Anderson, Mike Dash’s Batavia’s Graveyard, and Luc Sante’s Low Life.