El Lobo Returns Home

The battle over America’s wolves goes back centuries. In an excerpt from the forthcoming “Wolf Nation,” a journalist follows the release of a single family into the wild.

In the spring of 2015 I visited Wolf Haven International, a wolf sanctuary in Washington state, to witness the first litters of Mexican gray wolf pups born there in seven years. Via live remote cameras I watched as four gangly six-week-old male pups scampered and climbed atop their very patient father, M1066, nicknamed in house as “Moss.” The big-eared and fuzzy pups romped and feigned attacks with tiny sharp teeth, wrestling with each other, then racing into the tall cedar trees. These critically endangered Mexican gray wolves are growing up in the Species Survival Program (SSP) for possible reintroduction into Arizona, New Mexico, and Mexico. “They’re being raised by their parents, just like any wolf pup in the wild,” explained Wendy Spencer, Wolf Haven’s director of animal care. “Their world is so small now,” she added. “There is no concept of captivity or even humans for the pups. Just their parents, siblings, and home life.”

It’s a good and safe life at Wolf Haven, with its eighty-two acres of restored and biologically diverse prairie and oak woodlands, founded in 1982. These prairie lands are quiet buffers for this, the only wolf sanctuary in the world accredited by the Global Federation of Animal Sanctuaries. Here the carbon-rich grassy meadows offset climate change, a lush red and blue riot of native wildflowers like purple camas and golden paintbrush attract honey bees, and the moss-draped trees offer cool shade and refuge to the fifty-two displaced and captive-born wolves. Some have now found their “forever home” here. Of the several Mexican wolf litters born at the sanctuary, two family groups have already been released into the wild (Arizona): the Hawk’s Nest pack released in 1998 (part of the initial release) and the Cienaga group released in 2000 still survive today. This wolf family is one of the most genetically valuable in all of America’s captive population. By the late seventies wolf populations in the Southwest had crashed to a mere five wolves in Mexico and were all but eliminated in New Mexico and Arizona. Under the Endangered Species Act the federal government must work to recover this critically endangered species.

“All the Mexican wolves living in the wild today come from seven founding animals, composed of three distinct lineages,” Spencer notes. “They really need the genetic boost these new pups can give them,” she pauses thoughtfully, “if any of them are selected for reintroduction into the wild.”

That’s a big if, especially given the wolf-recovery politics in New Mexico and Arizona, where governors and wildlife commissions passed new rules forbidding any reintroduction of captive-born Mexican wolves. In the Southwest, Mexican wolves are “political footballs,” explains Linda Saunders, the director of conservation at Wolf Haven.

But now, as I watched, the six-week-old pups seemed to be playing their own kind of wolf football as one pup streaked across the screen and leapt on his father, M1066 (Moss), tackling his tall legs. Good naturedly, the father gave up trying to nap in the sun. He stretched, yawned, and play bowed to his offspring. Then all four pups again tried to clamber atop him, only to tumble off when he gave a gentle shrug.

Except for their long-limbed prance and exotic colorings—sable and gray-tinged fur—and their much longer snouts, the little pups could be mistaken for a litter of domestic dogs. But there is something much wilder in their golden eyes—and wariness—even as they play. These pups are hidden from any public view and see humans only for medical exams. If they are the ones chosen for release into the wild, they must remain very cautious of us.

“We’re so delighted that this spring three litters of Mexican gray wolves were born here,” said Diane Gallegos, director of Wolf Haven International. Gallegos is an energetic and articulate spokesperson for wolves, whether it’s as a member of the Pacific Wolf Coalition, the cutting-edge Washington Wolf Advisory Group, or even in a Seattle community gathering, a Wolf Salon, with a standing-room-only crowd of Millennials intent on learning more about wolf conservation. Since 2011 Gallegos has led Wolf Haven to become a leader in wolf-recovery efforts internationally. In the office, she posted me in front of another remote camera to take a look at a second Mexican gray wolf family led by the breeding pair, F1222 (Hopa) and M1067 (Brother), and their rambunctious pups.

“Oh, look, there’s the matriarch,” Diane pointed to the screen, where a rather blurry, but still majestic wolf ventures into the remote camera’s view.

Like her mate, this mother wolf, Hopa, is lean and almost impossibly long limbed, with an elegant auburn buff on her forehead, intense amber eyes, and a dark mask shading into a long, pale snout. Surveying her three sons, she looks at once dotingly maternal and yet watchful. Certainly she can hear the hidden remote cameras rustle in the leaves above as they shift slightly for better angles in the trees. A first-time mother, Hopa has quite an impressive history already—and she’s only four years old.

“She was born at the Endangered Wolf Center in Missouri,” the Mexican biologist, Pamela Maciel Cabanas, explained to me in her lilting accent. Like Spencer, Cabanas is an expert at wolf handling and very well versed in international wolf politics. Cabanas works with Wolf Haven’s Hispanic Outreach and is a liaison with Mexico’s Wolf Species Survival Program.

“In 2013,” she told me, “F1222 [Hopa] was transferred to the USFWS’s Sevilleta Wolf Management Center at the Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge in New Mexico for prerelease into the wild. Then, in the summer of 2014, Hopa was transferred to Wolf Haven, where she partnered with Brother, who was born at Wolf Haven in 2007. He is older than she is, but they are well suited and have been devoted parents to their offspring.”

This breeding pair was observed in a copulatory tie in the winter of 2015. Excitedly, Wolf Haven staff hoped for pups. Gestation in wolves is usually sixty-three days; by early May Hopa disappeared into her den. Via remote cameras the staff excitedly waited and watched to see whether the mother had whelped and was not ailing or enduring false pregnancy, common in canids.

Wolves are born blind, and their eyes open after twelve to fourteen days. With their distinctive brown furry capes and tiny, flattened ears, neonatal pups live underground their first weeks, denned up and protected by their mother. She rarely leaves their cool, musty underworld, like an earthen womb. When Hopa finally emerged from her den in early May of 2015 the Wolf Haven staff recognized that she was noticeably thinner—a sure sign that she had, indeed, given birth. For several weeks Hopa left her den only to eat, drink, or eliminate. After Memorial Day three tiny pups crawled out of their den, trailing behind her, their snouts raised high to sniff this new world of air and sheltering trees and sky.

They were clumsy and shaky as they took their first steps, their temporarily blue eyes now open, squinting against the sunshine. After nursing for so long or gobbling the regurgitated bits of food from their mother’s mouth, they now could nibble small bits of meat. They greeted their father, Brother, for the first time in the open air. In their next weeks, the pups would learn to play and socialize with their family and to follow their parents if frightened by an unusual sound or scent. For those first four to six weeks of the pups’ life outside their birthing den, none of the Wolf Haven staff came near. They observed and monitored the family only through remote cameras.

“Each wolf family is different, just like our human families” Spencer said. “I can already see patterns of behavior that will eventually contribute to their unique life story—routines, customs that may eventually be passed on to their wild progeny.” Some pups are more gregarious or curious and wander away from the den or their siblings. Some are more dominant, others more solitary.”

We watched as the father wolf endured his sons and daughter play by simply rolling over and yawning. He was about sixty to eighty pounds, and from tail to nose stood a little over four feet. The slightly smaller mother did a quick patrol of the underbrush, her ears perked, listening. As if on cue, a communal howl rose up in the sanctuary, where other wolves added their voices.

We all smiled as the father wolf raised his handsome head to answer a nearby howl with a long, sonorous bass song of his own. Startled, his pups glanced around, rather comically, bewildered at first. Then they lifted their small snouts and let out a series of yip-yip-yips—their very first tentative attempts at howling together with the family.

“Will this be the family chosen to go into the wild?” I asked Diane. I felt utterly privileged to observe these wolf pups without endangering or frightening them. How many people ever get to witness so intimately a wolf family simply going about their daily life?

“We just don’t know which or if any of these three Mexican wolf litters will be selected for reintroduction,” Diane said quietly. “We can only hope we’ll again get the call that our wolves will be the ones chosen to help the wild populations thrive.”

Later that spring two of the Mexican wolf pups from one of the other Wolf Haven litters died from parvo, a disease also common to domestic dogs. A Wolf Haven Facebook announcement of the pups’ deaths was met with a huge public outpouring of sorrow and support. These wolves are so precious and so essential to their wild cousins’ survival that every death is a disaster. That spring of 2015 I framed photos of the six-week-old Mexican gray wolf pups for my writing desk. Every day as I open their photos on my big screen, I gaze at the pups as if my thoughts can also protect them.

In my favorite photo—taken when the pups were crated up for their second medical exam—the frightened twelve-week-old pups huddle together in the fresh straw. Three of the pups flatten themselves in the straw, furry white-gray ears pitched forward. Their close-knit jumble is the very definition of a litter. One pup had climbed atop the others. All gazed directly out at the camera, their now-golden eyes topped by pale white and seemingly worried eyebrows. What dangers loom if they leave this sanctuary for the life of the wild?

El Lobo, the Mexican gray wolf subspecies, is one of the most highly endangered of all wolves. Smaller than other North American wolves, these Old-World wolves long ago crossed the Bering Land Bridge to colonize North America. They flourished in the Southwest and Mexico, despite being hunted, trapped, and poisoned for centuries. In 1977 in Mexico there were only five Mexican wolves surviving. These were captured, and three of them were then bred in captivity. In 1998 four more captive individuals from the Species Survival Program were added to the founding population, and some of these Mexican wolves were reintroduced into the wild, but only in the Arizona wilderness. Now, in 2016, there are still only 12 to 17 Mexican wolves roaming all of Mexico, and in America’s Southwest the population dropped from 110 wolves in 2014 to only 97 in 2015. Thirteen wolves have died, and only 23 pups survive now in the Southwest. At last census, there were 113 wolves in Arizona and New Mexico. Although there is a new urgency to reintroducing Mexican wolves in the Southwest because of the population decline, there are also political roadblocks to federal recovery efforts, especially from New Mexico and Arizona wildlife commissions.

Wolf Haven has kept readers alerted to the swiftly tilting politics of Mexican and gray wolf recovery in their quarterly Wolf Tracks articles. The sanctuary also posts popular videos of Mexican pups now thriving in the sanctuary on their website and Facebook page. Will one of the three Wolf Haven Mexican wolf families be chosen for reintroduction? For a time prospects looked dim. In the fall of 2015 the New Mexico Game and Fish Commission denied permit requests from the US Fish and Wildlife Service for any new release of Mexican wolves raised in captivity. This was a surprising blow not only to a struggling wild population and to Wolf Haven but also to Ted Turner’s Ladder Ranch—a prerelease wolf-recovery facility that has been vital to Mexican gray wolf recovery since 1997.

Ranchers opposed the release of any more wolves into New Mexico, citing that in 2015 there were thirty-six confirmed wolf kills on their livestock. The USFWS had asked for release permits for up to ten pups (to cross-foster with wild populations) and one pair of adults and their offspring. Cross-fostering is a survival strategy of moving captive-born pups when they are less than ten days old to wild dens in the hope that the wild wolf mother will also nurse and raise the captive-born pups alongside her own. Cross-fostering has also worked in the wild when pups are transferred from one wild den to another.

This is a very difficult technique because it depends upon so many variables—excellent weather for transport, discovering the exact location of the wild wolves’ den, and the wild mother’s acceptance and ability to nurture nonbiological pups. In 2015 the first-ever captive-to-wild cross-fostering for Mexican wolves was attempted. Two captive-born sister pups, Rachel and Isabella, at Minnesota’s Endangered Wolf Center were transported to Arizona with the hope of finding a wolf mother in the wild. But biologists on the ground failed to find the wild den, and Rachel and Isabella were returned to the Endangered Wolf Center and to their mother, Sibi, a very nurturing matriarch. Though cross-fostering is risky, it is an important element in helping this critically endangered species.

There are fifty-two facilities in the United States participating in the Mexican wolf Species Survival Program, with a current captive population of 270 wolves. These SSP programs await word from the federal SSP program for any chance of reintroduction to join the wild Mexican wolves surviving in the United States. When Arizona, which has a slightly larger wild population of Mexican wolves, denied any federal permits for the release of captive-born wolves, the situation looked really grim for reintroducing the three families of Mexican wolves at Wolf Haven. This was especially troubling because Wolf Haven International has had two family groups successfully released previously (1998 and 2000). Some of the very first Mexican wolves released back into the Southwest and still surviving came from Wolf Haven.

The Wolf Haven family had had very limited contact with human beings, but what would the effect be of their journey by highway, by plane, and then overland from New Mexico to Mexico?

Because of New Mexico’s permit denial, the window for any 2015 release passed, and everything was on hold again for all captive-born Mexican wolves. But then the USFWS announced that it would simply go ahead with plans to release more Mexican wolves, over the objections of the New Mexico Game and Fish Department. The majority of the state’s residents welcomed this decision to proceed with release, and a strong Santa Fe New Mexican op-ed, “Releasing Wolves the Right Thing to Do,” echoed this pro-release sentiment: “Good for the government. Managing the well-being of wolves in the wild cannot be left to individual states. Wolves don’t recognize boundaries, either between states or countries.” The editorial concluded, “It is clear that many people want wolves to die out. But the occasional loss of livestock is no reason to destroy one of God’s creatures. . . . By moving ahead despite state opposition, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is giving these wolves a new lease on life. And that’s as it should be.”

Everyone waited anxiously to see if New Mexico would relent and, as its major newspaper advised, “do the right thing.” The state did not agree. But it did move a little. In February 2016 the state’s game commission again granted Ted Turner’s Ladder Ranch its historical prerelease permits to hold wolves at the Ladder Ranch until they could be moved to Mexico.

I happily heard the good news from Wolf Haven that one of the Mexican wolf families—Hopa and Brother, with their three yearling pups—were chosen for release into the wild. The family had already been identified for release into the wild in Mexico back in July of 2015. These were some of the six-week-old pups I’d first seen last spring. Now, at last, they were going to their native Southwest. New Mexico’s game commission’s unanimous decision to renew the Ladder Ranch’s permit to prepare Mexican wolves for wild release came as a surprise, as just one month earlier they had denied it. But it was no surprise to Mike Phillips, executive director of the Turner Endangered Species fund. Phillips noted that “the commissioners indicated they saw a way forward. We acted on that hope.” The fact that the wolf family was to be released in Mexico, not New Mexico or Arizona, might have been why the commission reversed its earlier permit denial. “It’s the beginning of us moving back to where we were,” Phillips added.

Mexico began its wolf reintroduction program in 2011, and in 2014, the first litter of Mexican gray wolves was born in the wild there in thirty years. “This first litter represents an important step in the recovery program,” Mexico’s game commission said. “These will be individuals that have never had contact with human beings, as wolves bred in captivity do.”

The Wolf Haven family had had very limited contact with human beings, but what would the effect be of their journey by highway, by plane, and then overland from New Mexico to Mexico? Everyone at the sanctuary began the protocol for release with a sense of excitement and urgency. The date for the spring 2016 transport was imminent.

At Wolf Haven the forest is afloat in cool mists like a Chinese silkscreen. And the wolves are already howling—the ancient communal harmonies of high-pitched yips, eerie whines, and haunting keens that I never want to end. How can a wolf’s howl sound both elegiac and triumphant? The woven wolf music is so intricate and multilayered, with unexpected baritone riffs and ultrasonic descants. Their voices improvise and counterpoint, like animal jazz. A song sometimes tender, sometimes fierce, always mesmerizing.

“You never get tired of it, do you?” whispers Diane Gallegos, as she greets me at the sanctuary. We are all being respectfully quiet so as not to disturb the many wolves who have already sensed that something is up. “When we hear the wolves howling here in the sanctuary, no matter how many times a day, we just stop and listen,” adds Gallegos.

It’s a sound that so few people ever get to hear, especially in the wild, which is where these Mexican gray wolves are now at last headed. The wolf family will be transported by plane to Phoenix, then driven in a van all night to Ted Turner’s Ladder Ranch in New Mexico, near the Gila National Forest, the sixth-largest national forest in the United States. The Gila Wilderness was the first designated wilderness reservation, in 1924. The transport and journey to New Mexico will be difficult; if it goes off without incident, the Mexican wolf family will spend the next three months in the ranch’s large canyon enclosure, acclimating to the high desert and arid climate of their ancestors.

“Quickly,” Diane tells me and the photographer, Annie Marie Musselman. “You don’t want to miss this!”

Annie heads into the sanctuary, heavy burdened with cameras, and I go into the office, where I will watch the wolves as I have before, via live remote cameras. Very few of the staff are allowed to assist with the delicate and skilled work of capturing the five members of this Mexican wolf family. Dr. Jerry Brown, the Wolf Haven vet of thirty years; Pamela Maciel, the Mexican wolf biologist; and Wendy Spencer are among the other animal care staff in the careful operation. All are highly trained in what’s called a “catch-up” and final medical exam of the wolves.

One might imagine catching wolves to be a risky and fearsome job. Images of menacing growls, gnashing fangs, all the Discovery channel documentaries of vicious wolves attacking prey come to mind. But this catch-up is more like a well-choreographed dance or mime. Everyone in the enclosure is silent. When absolutely necessary, only Wendy speaks sotto voce.

The father wolf, Brother, and his yearling pups were born at Wolf Haven, and this is the first time any of them will ever leave their sanctuary. When he sees the crates, one yearling jumps atop the reinforced plastic kennel and uses it like a launching pad to leap into space and crash down on the forest floor. The pups have often played a kind of how-many-wolves-fit-on-the-roof-of-their-wooden-den-box. Answer: all five, including the parents. But this is a morning unlike any other in the pups’ lives. The close-knit family takes its cue from the matriarch, Hopa.

“She’s calm, but really terrified,” Gallegos tells me. “She’s poised like the family matriarch that she is, but she’s also shaking.” Gallegos is still whispering, even though we are in the office. Any stereotype of ferocious wolf attacks fades when we witness their fear. It’s a reminder that wild wolves are instinctively very wary of humans and spend most of their time in the wild trying to avoid or escape our attention.

Quietly Gallegos explains what’s happening on the screen with six people, each carrying a lightweight, four-foot-long aluminum pole with a padded Y at the end. “With each wolf, they’ll slide that Y-pole and gently put pressure on the neck and haunches. We don’t use the traditional catch poll with its lasso or rope. That can injure the wolves as they race away and then swing from their necks on the catch pole. Instead, we were trained by Dr. Mark Johnson, the wildlife vet for the Yellowstone wolves, to use this efficient but light pressure so as not to stress the animal.”

Dr. Johnson visits Wolf Haven yearly for wildlife-handling classes offered to wildlife agency personal and other federal, state, and tribal wildlife professionals. Others who take the class are zoo and sanctuary employees and volunteers, animal control officers, and university students. Dr. Johnson’s philosophy is visionary and compassionate. “There is no room for ego when handling animals,” he writes. When catching-up a feral dog or a captive wolf, he asks wildlife handlers to use this as an opportunity to “explore our connection with all things and to explore who we are as a person. This is a profound opportunity . . . exhilarating, sacred, and sad.”

Gazing into the grainy remote camera screens, it looks like everyone is silently moving underwater.

It is a profound experience, even to watch over remote cameras, as the highly trained wildlife handlers stand in a silent line waiting to catch-up the next wolf, a yearling. None of the staff seem nervous or tense even though they are inside a wild wolf enclosure.

“No, the people are not frightened,” Gallegos nods. “They’ve all been well trained. It’s the wolves who are afraid.” We watch the action a few more minutes before she adds, “The wolves are now hunkered down, frozen in fear. But we keep it really calm, and animals get used to seeing us at least every year when we do the medical exams and vaccinations.” Gallegos pauses and adds, “Like Lorenzo, the very first animal catch-up that I was involved in. As soon as we walked in with our Y-poles, the wolf ran into the sub-enclosure, and it was done. Because he recognized, ‘Oh, I know what I need to do here.’”

“The catch-up is very low stress. It’s quick.” Gallegos explains. “It’s like the techniques used in agriculture when a shepherd shears sheep. If you can make it a positive experience for that ram, then the next time you do it, the animals are not stressed out.”

“Like Temple Grandin inventing those hug boxes for cows,” I nod.

Grandin, a high-functioning autistic author and inventor, revolutionized the cattle industry by designing more humane wooden chutes that gently squeeze cattle into long, narrow corrals. The chutes actually calm the cows, much in the same way Grandin learned to soothe her own autistic anxiety by inventing a hug box for herself. Grandin’s groundbreaking research has radically changed animal science, and her animal welfare strategies now set the standard for the cattle industry. Grandin’s many books explain how animals think in pictures, like herself and many other autistic people. What pictures must now be fleeting through these wolves’ minds as they await catch-up?

Gazing into the grainy remote camera screens, it looks like everyone is silently moving underwater. Throughout the wolf family’s enclosure and the prerelease area the staff has hung huge sheets of canvas. These brown sheets easily herd the wolf family together, much the way ranchers use “fladry” on their fences to ward off wild wolves. For some unknown reason, wolves will avoid those flapping red flags or the canvas drapes.

The wildlife staff handle each animal one at a time, and usually only one or two people restrain the animal. Whether it’s some instinctive memory of being carried by the scruff of the neck by a trusted mother or the experience of being captured once a year for medical exams, the wolves are gently directed toward the safety of their crates, which become instant dens.

The three yearlings and their father, Brother, are all quickly crated. Not a howl, not a moan or a whine. The wolves are as mute as the people. Dr. Brown is quickly giving each wolf in the family a check-up. All looks good to go, he nods.

“It’s fast and efficient,” Gallegos murmurs as we watch. “Because they’re going to endure so much after this. Such a long trip.”

“Are they tranquilized?”

“No,” she replies firmly, “they can’t be. We don’t usually tranquilize our animals unless we absolutely have to. To fly in a plane tranquilized could be really dangerous. You don’t want them in cargo, unmonitored, choking. You want them to stay awake. It’s a two-hour flight and good, smooth weather, so we hope it will all go well.”

Still in the sanctuary, the mother wolf, Hopa, has denned up. She is the last to be shepherded into her crate. I watch, transfixed, as Spencer almost tenderly reaches into the den with her Y-pole. The mother wolf instantly hunkers down at the touch of the Y-pole on her neck. Quickly, as someone else rests the Y-pole on the mother wolf’s haunches, Wendy secures a blue head cover over her face for safety. Covering their eyes and head always quietens wild animals, like horses or animals injured on the road. Something about not being able to see immediately reassures the animal. Safely muzzled, Hopa is lifted into the comfort of her own crate. All five of the family are now ready to go to the airport. The whole catch-up of the wolf family has taken just one hour. Smiling and relieved, the Wolf Haven staff emerge from the sanctuary, followed by Wendy driving the van. Inside, the wolves, each in their own crate, are utterly still.

Annie’s photos and videos are all we see now on the screen. The most striking portrait of all is the mother wolf, an image I’ll never forget: crouched at the very back of her crate, as if to bury herself in the blonde straw, she gazes out, her ears perked to fathom each voice or strange sound; her golden eyes wide, wary, preternaturally focused; her distinctive rust- and black-colored fur dense and beautiful. But her dripping black nose betrays her terror. Her flanks are trembling. Hopa doesn’t move or thrash or try to escape. She looks hypervigilant but eerily calm at the same time After all, she has a family to protect from whatever strange journey is being asked of her—nothing less than leading her pups and her mate into the complete unknown. The recovery and resurrection of an entire species await her. When I study this matriarch’s face I read both fear and courage. I’m reminded of the adage that, in humans, the bravest of us are those who actually feel fear and yet still perform some perilous feat.

This wolf family must now travel to New Mexico and beyond into unfamiliar wilderness that has always been hostile to wolves. They may lack the skills to survive in wild, rugged terrain with not a lot of prey. If they kill livestock, Mexican ranchers might regress to their history of hunting wolves. It is difficult to think of Hopa, and her mate, Brother, and their yearling pups being so vulnerable to hostile forces as they return to repopulate their native territory. But it is vital if their species is to again take a foothold in Mexico and the American Southwest. As I stand a little distance from the white van that now holds the fate of this wolf family in their five crates, I can’t help but feel both exuberant and anxious.

The amiable Wolf Haven vet, Dr. Brown, notes that all the wolves are healthy. “They all handled it pretty good,” he says, “not a lot of jumping around and craziness.” He has drawn blood from the matriarch to discover if she is perhaps pregnant.

Pamela Maciel, reports, “Now the wolves are very calm, because they are so afraid. Terrified. Trembling. It’s like they just completely freeze.”

I don’t ask anyone whether they are sad to see this wolf family leave their haven. It’s obvious from their faces.

There are still two other Mexican wolf families left in Wolf Haven’s sanctuary. They too are part of the Species Survival Program and await possible release, perhaps even as early as next year. “It’s so exciting,” says one of the Wolf Haven staff. “They will at last be wild and back where they belong.”

I stand a little distance from the van that will carry this wolf family to the airport. Inside my jacket I reach for the wolf necklace that has accompanied me on all my wolf research trips. The silver is cool, but the wolf teeth are warm and sharp against my fingers. These are Mexican wolf teeth. After a century they seem almost alive again.

There are too many wolves to fit on one Alaska airlines flight. Moving a whole family group is very different from moving just one animal. So they fly on two planes. One wonders what Phoenix-bound passengers might think if they had any idea that wolves are also aboard their airplane.

“Typically we drive,” Gallegos explains. “But when it’s this long a trip—twenty-eight hours—it’s better for the animals to fly.”

Wendy sends a Facebook photo from the Alaska Airlines cargo area where one large metal cart now holds all five of the crates with the wolf family. In the photo Wendy looks both happy and yet also alert as she poses with an airlines employee. So far, so good.

Imagine what it must be like for these animals who have always known only the quiet and calm life of family and sanctuary to suddenly hear the rumble of SUV tires along a busy freeway, the scream of jets at the airport, the sensory overload of what must seem like multitudes of people jabbering, and the terrifying roar of a jet engine and perhaps even a little turbulence as they fly midair. What does the grease and jet fuel smell like to them? Can they even begin to make sense of the scent of so many passengers? In the cargo hold, which is unregulated and always icy cold, the only thing familiar now is family, the scent and sound of one another in nearby crates.

For the next twenty-four hours those of us who know the importance of this Mexican wolf transport, including the thousands following it on the Wolf Haven Facebook page, will anxiously await word of the wolf family’s journey. Radio silence. Then the next day an email from Spencer: “Transport went as smoothly as we could have hoped for (though, no doubt, the wolves were terrified).”

When they opened the crates at 4 a.m. at Ladder Ranch after the all-night transport the father, Brother, and the pups were too afraid to emerge. But the mother, Hopa, raced right out of her crate and into her new life. Normally Spencer would have let the other wolves emerge on their own. But after twenty-eight hours she needed to make sure Brother and the three yearlings were unharmed by the journey and could move easily. “They seemed okay,” she wrote, “if a bit stiff. We had to take the top off the crates and literally gently dump them out.”

The next morning Spencer and Chris Wiese, who manages the wolf-release program at Turner’s Ladder Ranch, drove to the blind to better observe the wolf family. Hidden, Spencer and Wiese could watch the wolf family explore this new canyon land of mountains, prickly sagebrush, hot springs, and wide, semi-desert mesas. Once back in the wild, these Mexican wolves may travel forty miles a day at about thirty-five miles an hour. They can swim as much as fifty miles. With such an expanse of territory to reclaim, the wolves can roam together in their trademark single-file line, moving in what’s called a “harmonic gait.” The back paws fall exactly where the front paws have already landed, giving their movement a “rhythmic job that conserves energy.”

“We saw them eating, drinking, chasing ravens, and even snoozing. They looked very much at home—much more so than in the Evergreens of Washington. It was like they had been here their entire lives,” Spencer told me happily. While Spencer and Wiese observed the wolf family in their new habitat, several golden eagles circled above. “We should all feel so proud and honored to be a part of something so much bigger than ourselves.”

News of cross-fostering success soon buoyed hopes for the recovery of Mexican gray wolves in America’s Southwest: in May of 2016 the USFWS placed two captive-born, nine-day-old wolves—nicknamed Lindbergh and Vida—into a wild den in New Mexico. The wild mother wolf had her own litter of five pups and adopted the two newborns to raise as her own. Missouri’s Endangered Wolf Center calls cross-fostering “a unique and innovative tool” to increase genetic diversity and help grow this sadly dwindled population.

New Mexico immediately announced its plan to sue USFWS to stop the federal plan to release a single family of captive-born wolves and halt any more cross-fostering of wolf puppies in the wild. The Department of Fish and Game asked a federal judge for a temporary restraining order requiring that the feds get state permission for any more wolf releases. In June of 2016 a federal judge granted the injunction. However, the state’s request to remove the cross-fostered wolf pups was denied. Many scientists and wolf advocates fear that New Mexico’s resistance to continued wolf recovery is a delaying legal tactic that will simply run out the clock on this highly endangered species that has already declined by 12 percent. Scientists point out that in the eighteen years since reintroduction in the Southwest the federal government has shot fourteen wolves, captured dozens more, twenty-one of which were accidentally killed in capture or counting.

Tensions between New Mexico’s state wildlife authorities and the federal government increased. In May 2016 a male wolf, M1396, in the Gila National Forest was captured in a steel leg trap and moved to a captive pen for the rest of his life. This wild wolf had been widely celebrated by Albuquerque schoolchildren. A sixth-grader had named him “Guardian” because “wolves need a guardian to keep them safe and help their population rise.” Guardian was native to the Fox Mountain Pack, one of nineteen wolf families whose territory ranges from southwestern New Mexico to southeastern Arizona. Guardian mated with a Luna pack female, and together they were raising pups. But after reports of livestock loss, the feds decided to remove Guardian from his family and pups.

This decision was greeted with dismay. A mate is very dependent upon male help in feeding and nurturing pups in their infancy. Removing the male not only risks losing the female and her new pups; it may actually increase the risk of livestock predation because without a male, the female can rarely hunt elk or deer, their usual food source. “It’s devastating to the pack to lose an alpha,” says Regina Mossotti, director of animal care and conservation at the Endangered Wolf Center in Missouri. “It’s like it would be to your family. Imagine if you lost your mom or dad at a young age.”

“Wolves do not purchase hunting licenses. . . . That, in brief, is what is wrong with wildlife management in America.”

The struggle between state and federal wildlife agencies over the Mexican wolf recovery continues. The Center for Biological Diversity urges that New Mexico should “extricate itself from the state politics driven by the livestock industry, stop removing wolves from the wild, release five more family packs into the Gila as scientists recommend, and write a recovery plan that will ensure the Mexican gray wolf contributes to the natural balance in the Southwest and Mexico, forever.” Even though the law demands that the USFWS fulfill the Endangered Species Act and wolf recovery has huge public support in the Southwest, the states still continue to resist. In late fall of 2016, an Arizona judge issued a court order requiring USFW to finally update a decades-old recovery plan for the endangered Mexican gray wolf by November, 2017. With only about 113 wild wolves in Arizona and New Mexico, this move toward increasing Southwest wolf populations is essential to recovering the Mexican gray wolf in America. “Without court enforcement, the plan would have kept being right around the corner until the Mexican gray wolf went extinct,” said the Center for Biological Diversity. This court order dismissed protests by ranchers and other antiwolf factions in favor of moving ahead with wolf reintroduction.

But the root cause of much antiwolf bias remains. Wildlife commissions reflect the preferences of their members. A recent Humane Society study of eighteen states’ game commissions revealed that 73 percent were “dominated by avid hunters, clearly unrepresentative of the state’s public they speak for, but in line with their funding sources.” New Mexico’s Department of Game and Fish receives $20 million each year from licenses bought by hunters, trappers, and anglers. Not much has changed since 1986 when Ted Williams wrote his famous essay, long before wolf reintroduction: “Wolves do not purchase hunting licenses. . . . That, in brief, is what is wrong with wildlife management in America.” But we are on the cusp of a cultural change in wolf recovery. As Sharman Apt Russel writes in The Physics of Beauty, “All Americans would feel better if we could agree to share our public land with one hundred Mexican wolves, a fraction of the wildness that once was here.”

At New Mexico’s Ladder Ranch Hopa and Brother and their young yearlings continue to thrive—and await release. Meanwhile extraordinary news came from Dr. Brown at Wolf Haven. Hopa was indeed pregnant when she endured the long transport from Washington State to New Mexico. In an email photo attachment sent by the Ladder Ranch, five dark-brown puppies huddle together in the straw of their den. Hopa and Brother’s family has now grown to eleven. At Ladder Ranch, Hopa and Brother and their nine offspring are growing strong as they roam and hunt in their new territory of crisp sagebrush and arroyos.

In the late fall of 2016, Mexico’s National Commission of Natural Protected Areas announced the third litter of wild-born pups had been sighted in the state of Chihuahua. This is the third year running that the breeding pair, M1215 and F1033, have produced pups, bringing the endangered Mexican wolf population in Mexico to 21 animals. And in October, 2016, a wolf family from a Mexican captive-bred facility released a wolf family into the wild. There is hope that Brother and Hopa’s family will be less threatened by poachers, because they will be released on semi-private land in Mexico.

As I read Wendy’s updates on Hopa and Brother, I often gaze at photos of this wolf family. These Mexican wolves are the small but strong-willed survivors who first captured Edward Seton’s admiration and respect in his “Old Lobo” stories. Hopa’s powerful life force also echoes the “fierce, green fire,” that once changed the heart of Aldo Leopold. The nearby Gila National Forest includes the Aldo Leopold Wilderness.

This wolf family is returning to a country where wolves were all but extinct for three decades, where wolf biologist Cristina Eisenberg’s Mexican grandfather ordered her father to kill wolves, but he chose to allow them to live on his own ranch land. Maybe Mexico will now lead the way in restoring this first wolf that crossed continents to claim North America. Maybe New Mexico and Arizona will once again allow the federal government to do their job required under the Endangered Species Act.

In December, 2016, Hopa, Brother, and their now nine offspring were at last released into the wild in Mexico. This successful release was the largest of its kind in either Mexican or American history. That snowswept evening, when the eleven crates were finally opened, the wolf family sprang out into the wilderness and freedom—fulfilling their long journey and giving hope for wolf recovery around the world. Wendy and Pamela from Wolf Haven helped release the wolves into a country that warmly welcomes El Lobo home. The next morning, Wendy sent me an email that said it all in one word: “La Liberacion!”

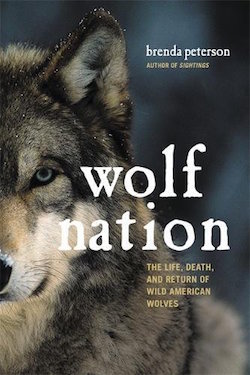

Excerpted from Wolf Nation: The Life, Death, and Return of Wild American Wolves by Brenda Peterson (DaCapo Press, Merloyd Lawrence Book, 2017).