From Cover to Cover

Music connects to memories, and so do album sleeves. From ELO’s spaceship to Róisín Murphy’s see-through top, the covers that made one writer a fan.

I am 39. Yesterday I played a compact disc on a real compact disc player, and remarked to myself how retro I was. I looked at the computer in the kitchen. It’s the only way my seven-year-old son knows how to listen to music. He can search Spotify and navigate iTunes, and he knows what a CD is, but he doesn’t see one very often.

The CD I played was Selected Ambient Works 85-92 by Aphex Twin. Just looking at its cover reminds me of the early ’90s, when I lived in a grotty shared house in a grotty town. The lad in the room next to mine was called Keith or Kevin, and he loved playing Talking Heads so loud it shook the cheap partitioning walls.

The memory rushes into my mind every time I listen to Aphex Twin. Or Talking Heads for that matter.

Album covers do that to me.

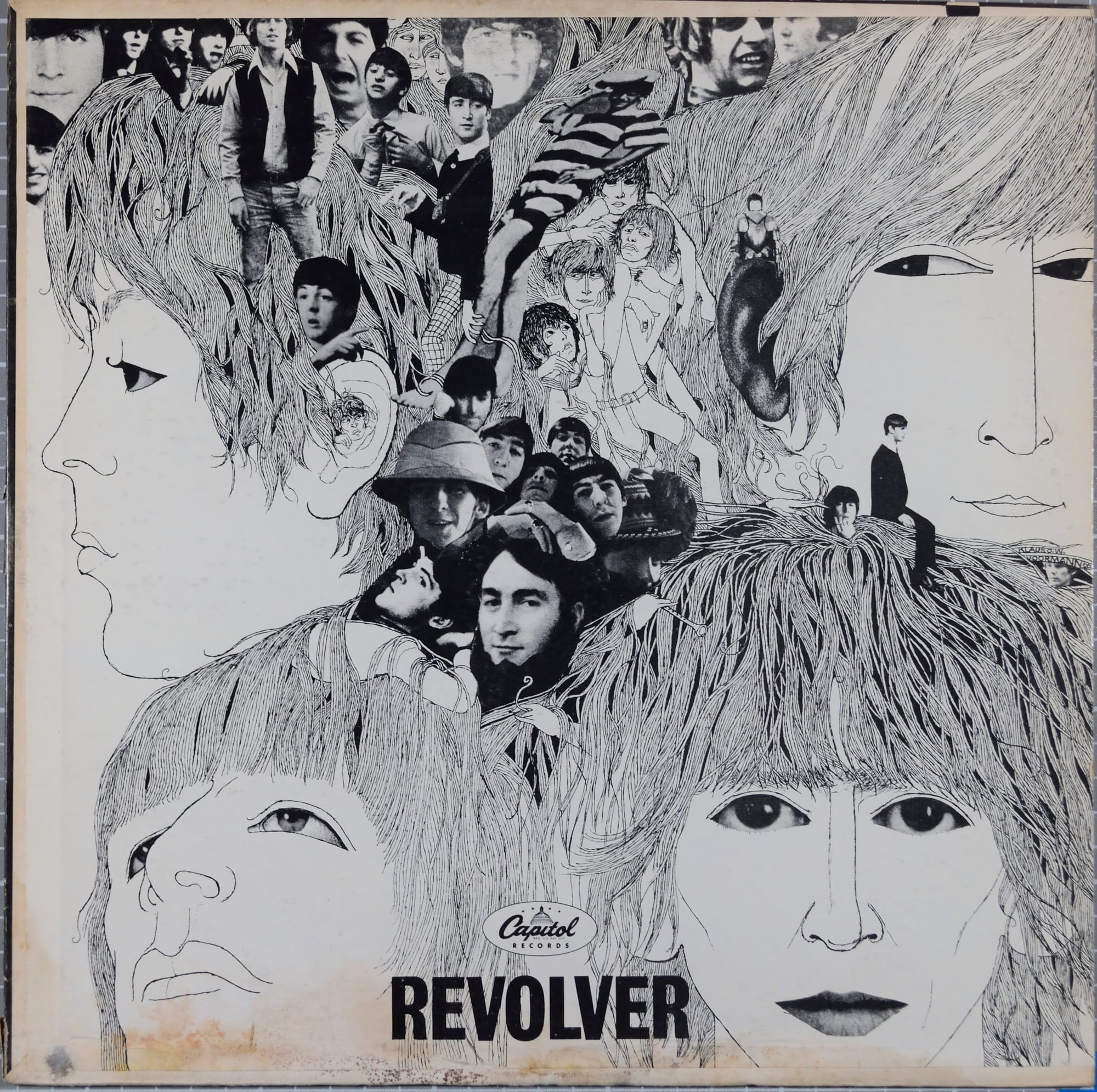

Revolver is a companion. It’s just there throughout my childhood, an object in the house that I take for granted like the armchairs and the kitchen utensils. And while I’m young, it doesn’t hold any special interest. But I know it intimately. I know every click, every key change, every chord progression. I sing along to it, dancing around like six-year-olds do. The sleeve is like a photo in the family album, a wedding portrait: something comforting. As I get older, the album becomes more important to me. In my 20s, I’ll start to grasp how important it is in the history of pop, what a difference it made when it came out. I’ll start to understand why my dad bought it in the first place.

That’s when I’ll look closer at that sleeve while humming along to “Eleanor Rigby.” I’ll notice that the four Beatles are all looking in different directions. George Harrison’s eyes are intent on the listener; Ringo’s are gazing at the sky, Paul’s are seeking something far off. And John Lennon is looking sidelong at Paul, the tiniest hint of a smile on his lips. What’s he thinking?

Nestled around them, clustered in their hair and even poking out of Paul’s ear are dozens of MiniBeatles, like swarming insects. They are the album’s musical ideas bursting out from the Beatles’ heads, crowding for attention and recognition and space. Perhaps George Harrison is looking at me like that to ask for help. “I managed three this time,” he’s saying. “That’s progress of a sort.”

Later still, I’ll read best-albums-of-all-time articles and they will always end with this, or Sgt. Pepper, or Pet Sounds, or OK Computer in the number one slot. I’ll own all four, and I’ll see what they mean. I’ll be thankful that I don’t have to write those sorts of lists for a living. It’s hard to make choices.

At seven, I am completely obsessed with space. I have seen Star Wars at the cinema with my mum, and consequently I am one of the cool kids. ELO’s Out of the Blue arrives on the shelf this year, and it takes me over.

I can put the LP on and lie tummy-down on the floor, my chin supported in my cupped hands, and gaze at the sci-fi sleeve for hours. I do exactly this, many times.

I take particular interest in the ELO spaceship. I examine the details. I am slightly critical.

For one thing, I know that spaceships should not be this pristine. Star Wars has taught me that space ships should be asymmetrical, tatty, dirty, elongated, and dark. ELO’s circular, bright, neon-sheened effort is wrong on so many levels. It’s a bit too Flash Gordon for my tastes. But I love it nonetheless. I stare at it. I take in the complex docking bay entrance, complete with what looks like a robot arm to guide the ELO shuttle carefully into position. I approve of this detail.

On the back—even cooler—part of the ship is incomplete. Girders of orbital glam-rock logo hang suspended in vacuum. Two more prog-rockers float aimlessly nearby, like they’re taking a break during a long recording session. Like they’ve nipped outside for a quick space ciggie.

Open the double album sleeve and there’s the interior—vast, dominated by two huge floating spheres. Alien brains? Destination planets? Between them stand two long-haired 70s prog-rockers in shiny space suits. This tiny detail, of course, seems perfectly normal and not at all out of place.

The control room is smooth, textured, nicely lit. The control panels look like the ones in 2001: A Space Odyssey, which I have watched with my dad. I didn’t really understand it at all, but I like the fact that these computers look like those ones. It fits.

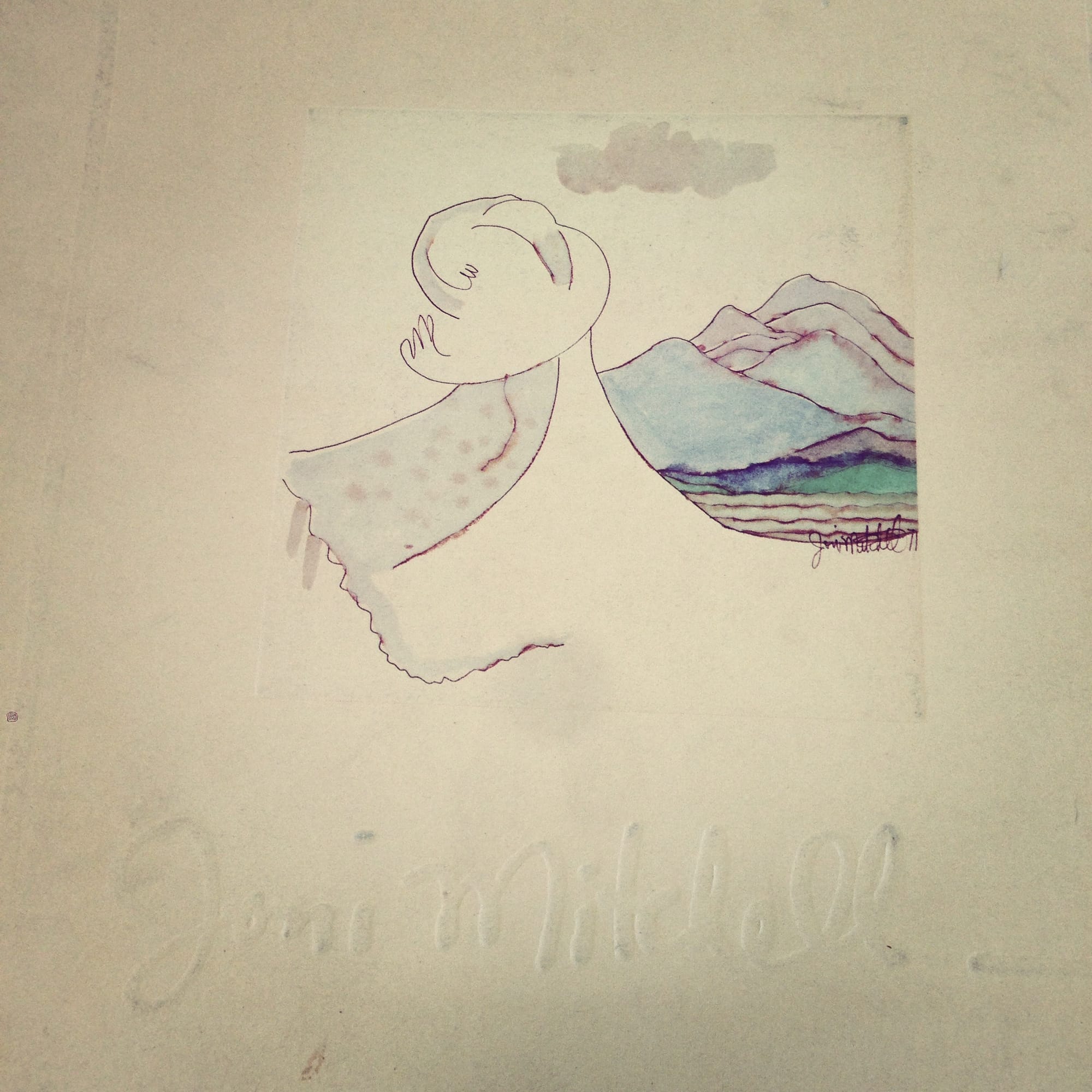

Like Revolver, I grew up with Joni Mitchell’s Court and Spark. It was always there in my dad’s house, and he’d play it often, so I just know it without knowing it.

In my early 20s, on an impulse, I buy my own copy. I see it in a store and the cover calls me over, saying “Hi again. Me again.” This time I don’t just let the sound wash over me, I sit with huge 1970s headphones on—my dad’s stuff again—and absorb it. My toes twitch. Joni’s voice drips over me like thick cream.

She painted the sleeve artwork herself. My dad told me when I was little, and I took in that fact the way kids take in their times tables and their table manners. Deep in my headphones, I sit with the CD artwork in my hand. It’s too small. The text isn’t textured as it was on the LP cover.

Thing is, this sleeve doesn’t say anything to me about the album. The mountains in the distance are clear, the figure in the foreground less so. (Is it Joni? Is she weeping? Is she just wearing a hat?) But when I see this picture, I don’t think of the music. I think of my dad’s living room. His taste in old furniture. His vintage hi-fi kit—good stuff it was. Great sound.

The rear sleeve shows a high-contrast photo of Mitchell, eyes closed, lips glossy. She looks like a model, or a pop star.

In a few years from now my dad will almost die from aplastic anemia. Some time after his recovery and return home from hospital, we’ll be in his flat—me, my brother, and him. Dad will say, “Let’s have some music,” and we’ll all pick this album. It brings comforting sensations, but none of us can put our finger on precisely what they are.

When I’m 12, my brother is 15 or 16, and has started listening to grown-up music.

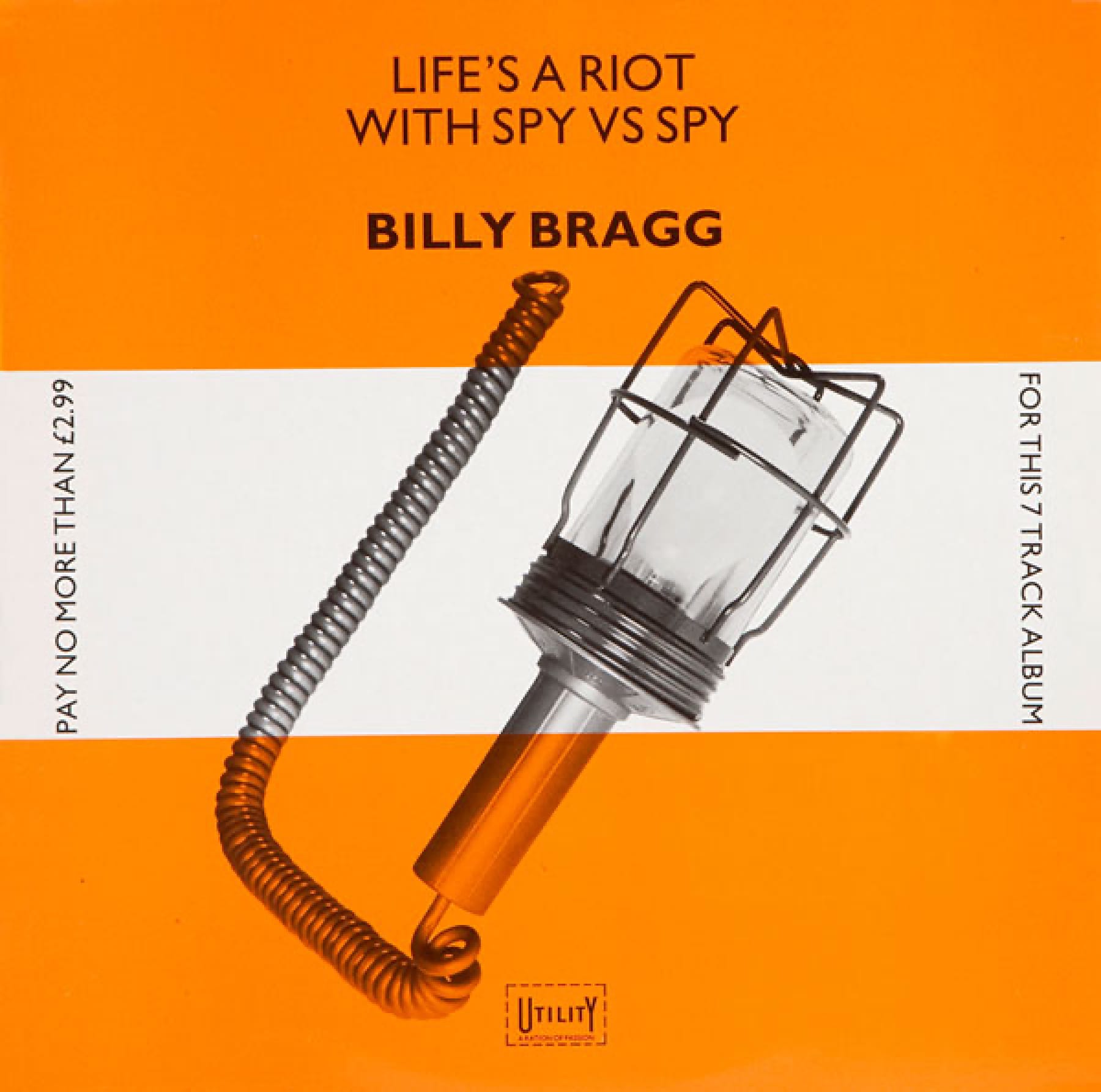

His growing interest in music will redefine my own tastes over the next few years, exposing me to stuff I’d otherwise have missed. The first unexpected experience is Billy Bragg’s Life’s a Riot, which he brings home in a plastic bag and plays on the living room stereo.

At first I’m not impressed. But soon I’ll put this album on more often, bellowing along to it with my very best Bragg impression.

The sleeve couldn’t be a further contrast from Out of the Blue. It’s basic. It’s stripped down. It’s working-class. Tools are for work, not for daydreams. This music is real life; love, work, jealousy, sadness. No space ships required.

And to one side, as if dictated by Bragg himself, are the words “Pay no more than £2.99 for this 7 track album.” You read them and you hear Bragg’s voice in your head. It’s British fair play at its most British, and certainly its fairest: The whole album lasts just over 15 minutes, so why on Earth pay inflated standard album prices? You pay your money and you get your songs, but if you’re only getting so much song, you should only pay so much money. You can almost hear Bragg sitting back in his chair, satisfied that he has done right by his audience.

I learn all the words off by heart. Decades later, alone in the car on long boring journeys, I still sing “Milkman of Human Kindness” to myself. My very best Bragg impression has improved with age.

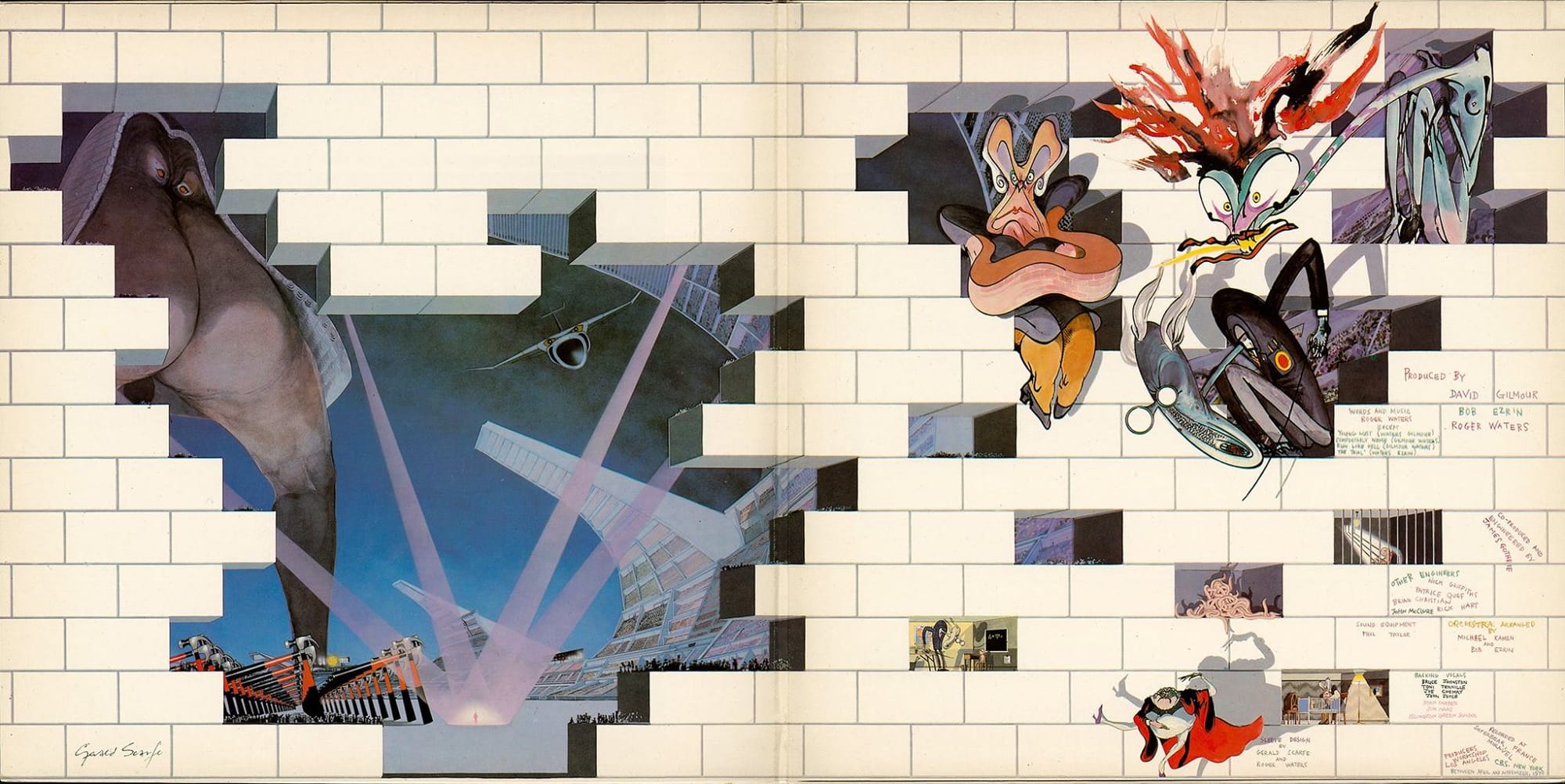

Around the same time, I’m exploring my stepsister’s music. Nestled among the Joni Mitchell and Chicago LPs on my dad’s shelf is her copy of Pink Floyd’ The Wall. It’s tantalizing because it’s so different.

This is where I discover that pop music can be about everything, not just about love and dating and the happy, sappy crap that’s been at the top of the UK charts throughout my formative 1970s. These people are angry. They’re making records about terrible things. I listen and grow thoughtful.

Of course the plain wall of the exterior isn’t a barrier at all, it’s an invitation to open up the double gatefold sleeve (that’s what they called them in those days) and stare wide-eyed at Gerald Scarfe’s illustrations of the appalling Wall characters. Those marching hammers like Soviet soldiers, that jet plane with eyes and an expression that looks to me rather happy and friendly (although I’m sure that wasn’t the intention).

The schoolmaster’s empty eyes. The worms. It’s all so… intense. No one can draw hatred like Scarfe does here, no art I’ve previously encountered has so perfectly summed up loneliness and fear. These pictures scream “Fuck You” in a way the music can’t quite bring itself to.

I’ve only just started to realize that art can be angry, that art can spit and bite and snarl. Those massive headphones on my head once more, I can flick through Scarfe’s hand-written lyrics as I sing along. I’m still enjoying myself, I’m sure of that. But it’s not the same sort of joy, is it?

Since we’re schoolkids when “Another Brick in the Wall Part 2” is released as a single and reaches number one, we think it’s hilarious to sing it as loud as we can while marching, hammer-like, around the school playground. “Hey! Teacher!” we smirk, “Leave those kids alone!” We think we’re so funny.

As an adult, I can nod enthusiastically during dinner parties while my fellow guests discuss their favorite record sleeves of all time. I can go out and waste money on books that claim to list the top record sleeves of all time.

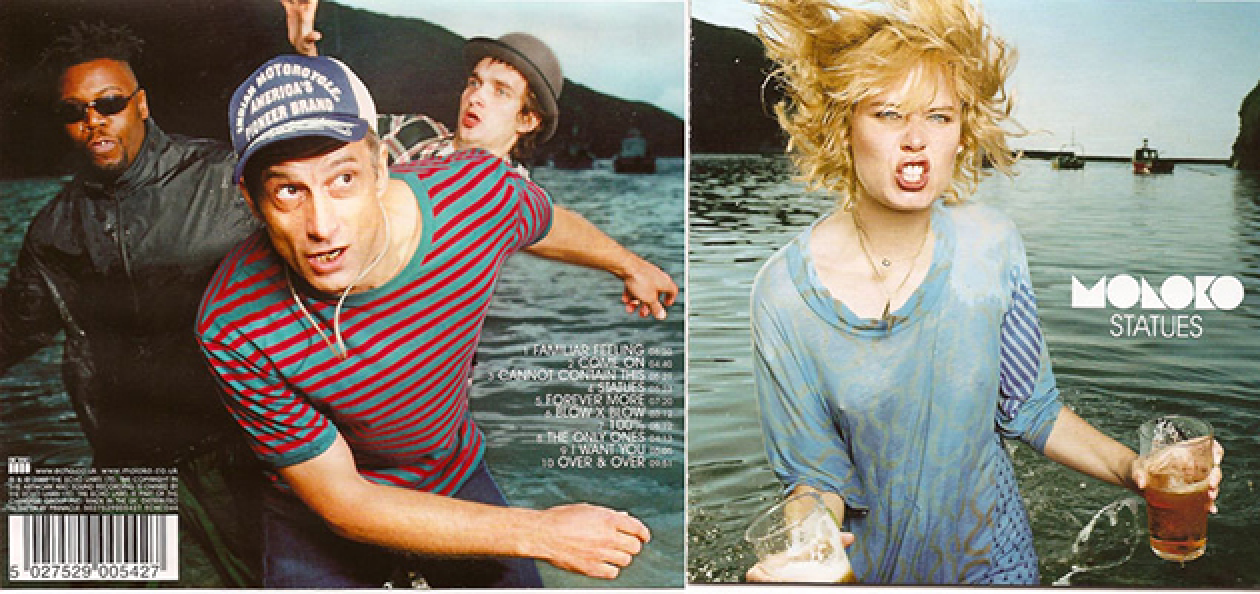

But I’ll know my favorite record sleeve of all time when I see it, and it will be this one. This Moloko sleeve is life itself.

On the front, beautiful singer Róisín Murphy wobbles drunkenly, thuggishly, threateningly before me. She holds those two pints of beer and looks like she’s going to hurl them in my face, simply for being cheeky enough to look at her. She’s snarling, aggressive, soaking wet. Not, um, wearing a bra.

And she doesn’t care. She gives not a flying fuck what I think, what you think, what anybody thinks, because she is having the time of her life larking about in freezing cold seawater with her mates.

Yes, open the sleeve up and there they are, you see the rest of the band. In the same spot, just as wet, looking just as ridiculous. More so, in fact. Open up further, look within, and now you know that Murphy’s tough act is just a joke. She’s just pulling stupid faces. It’s all just a silly stunt, but it works incredibly well.

Not least because the photography is technically perfect, as well as funny and entertaining. The grim sky and silhouetted boats in the background are the ultimate contrast to the band’s antics. The musicians are lit up wonderfully. Now that I have adult opinions about these things, and now that space ships aren’t quite so important as they used to be, I find myself wondering: Was this the plan? Did the band ask photographer Elaine Constantine to do a shoot while they larked on a beach? Or was this what happened after the official photo shoot? Was this just an idea hatched in the pub? “Let’s take some pictures on the beach! Race you there!”

Because that’s what it feels like. That’s the wonderful life and spirit in this sleeve. It celebrates spontaneity, doing stuff ’cause it’s fun, having a drink and a laugh and a joke whenever you can. It’s fun, and it’s infectious, and track three says it all: “I just cannot contain this.”