Going Postal Goes Abroad

From 2011, knowing the history of the phrase “going postal” helps us understand how America exports killing sprees to angry young men worldwide.

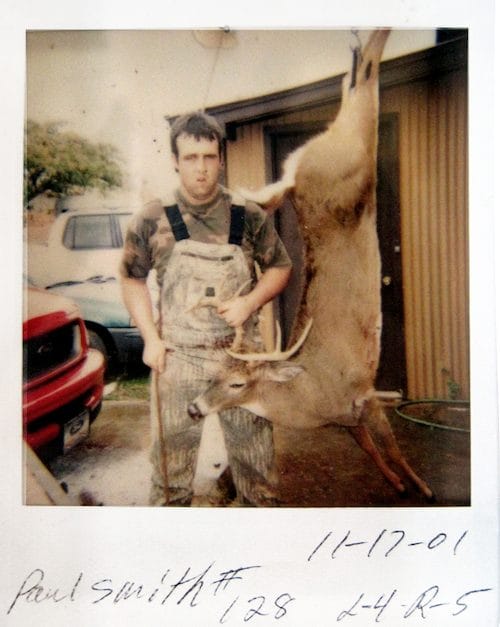

Early on the morning of August 20, 1986, a 44-year-old mail carrier named Patrick Sherrill arrived for work in Edmond, Okla., armed with three handguns. The previous day, Sherrill, a shy, solitary Vietnam-era veteran who lived in the house he had shared with his mother until her death eight years before had been warned by his supervisors he could lose his job if he didn’t shape up his work habits. Now, dressed for work in his blue mail-carrier’s uniform, Sherrill walked up to one of those supervisors, Rick Esser, and shot him dead.

For the next 15 minutes, Sherrill stalked the halls of the building shooting his fellow postal workers as they stood at their mail-sorting stations, too shocked to run. He said nothing during the entire episode, according to surviving witnesses, just made a quiet circuit of the building, carefully shutting doors behind him to prevent anyone from escaping. By the time Sherrill turned his weapon on himself he had killed 14 people.

Twenty-five years after Sherrill’s rampage in Oklahoma, Anders Breivik, another gun-toting loner with a close attachment to his mother, set off a series of explosions in central Oslo, Norway. Then he drove 19 miles to a youth camp run by the country’s left-wing Labor Party and opened fire on defenseless campers. Breivik didn’t say much, either. Dressed in a police uniform, he told campers he was conducting a security check following the Oslo attack. “He was standing just by the water, using his rifle, just taking his time, aiming and shooting,” one survivor told the New York Times. “It was a slaughter of young children.” By the time Breivik surrendered to police 77 people were dead.

On the surface, there would seem to be little connection between these two incidents. Sherrill was a classic sad sack, a lonely, middle-aged man who spent his spare time reading Guns and Ammo and talking on ham radio. Breivik, on the other hand, is a coldly calculating right-wing extremist who spent three years writing a 1,500-page manifesto detailing his rabidly anti-Muslim views before gathering an arsenal of firearms and six tons of explosives in preparation for his politically motivated attack.

Yet when the horrific news came from Oslo last month, one of the most disheartening elements of the attack was how familiar it all seemed. In this country, we have become so inured to stories of men going on inexplicable killing sprees we’ve coined a name for it: “going postal.” Every few months, it seems, some crazed gunman opens fire on a quiet college campus or shoots a congresswoman outside a suburban supermarket. As we approach the 25th anniversary of the massacre that gave us the term “going postal,” lone gunman sprees are not only frighteningly common in the U.S., but have spread overseas, even to countries with stricter gun laws and placid, homogenous societies. A growing proliferation of guns and a media culture soaked in violence no doubt contribute to this alarming trend, but a more subtle culprit may also be at work: These bloodthirsty quests for empowerment at the point of a gun may well represent the dark underside of a distinctly American culture of personal freedom and entitlement we are exporting around the world along with our iPods, TV shows, and free-market democratic ideals.

Patrick Sherrill did not invent mass murder, or even lone-gunman killing sprees. In Lone Wolf: True Stories of Spree Killers, author Pan Pantziarka cites Howard Unruh, a World War II vet who in 1949 went berserk and killed 13 people in his hometown of Camden, N.J., as “the father of modern mass murder.” Another famous example is Charles Whitman, who climbed a tower at the center of the University of Texas’ Austin campus in August 1966 and shot 16 people with a high-powered rifle.

A suicide bomber goes into his operation knowing not only that he is going to die, but that he is going to die first. No turning the tables on the boss at the end of a .45 automatic. No quiet satisfaction of hunting people like vermin. No thrill of playing a video game with live victims.

Still, in the quarter century since Sherrill’s 1986 rampage, spree killings have ticked notably upward, both in this country and abroad. In the quarter century since the Sherrill incident, the U.S. Postal Service has seen at least a dozen more episodes of gun violence involving disgruntled employees at its offices that have resulted in 24 deaths. Overseas, in August 1987, a year after Sherrill’s spree, Julian Knight, a disgruntled former Australian army cadet, positioned himself behind a billboard at a busy intersection in Melbourne and opened fire, killing seven people and wounding 19 more. That same year in the quiet English town of Hungerford, an unemployed laborer named Michael Ryan suddenly snapped and shot 16 people, including his own mother, before committing suicide. Since then, men with guns have gone on killing sprees at work places, at schools, at tourist sites, on busy streets – essentially anywhere large numbers of people are likely to congregate. If you look at the records of lone-gunman mass shootings over the past 25 years, Americans still top the list, but killers have come from around the globe, including England, Australia, France, Switzerland, South Africa—and now Norway.

If spree killings are a kind of social epidemic, then the strongest single strand in its DNA is the proliferation of firearms. Americans, of course, are notorious for their love of guns. In a 2010 Harris Poll, 32 percent of respondents reported having at least one gun in the home, and depending on whose statistics you believe, there are between 190 million and 280 million guns in circulation in America today. But you don’t have to be American to buy a firearm. According to the Small Arms Survey, there are roughly 875 million firearms in circulation around the globe, with up to 900,000 more being produced every year. Many of the countries seeing American-style spree killings have strict gun laws, including, in the case of Norway, complete bans on automatic weapons, but with careful gaming of these laws men like Anders Breivik can amass more than enough firepower to do the job.

If would-be spree killers have a harder time buying firearms outside the U.S., they watch and play the same violent movies and video games that we do, and have access to the same Internet teeming with websites and chatrooms devoted to gun tactics and training and to spewing hatred. These, too, are likely strands in the spree killer virus, in that movies and video games stoke the fantasies of would-be killers, while the web offers explicit directions and rationales for carrying them out. And, of course, all cultures have their loners and losers, the sad, angry, mentally unstable guys living at home with their mothers, fondling their weaponry.

But these factors speak only to the conditions that enable killing sprees. They don’t take into account the crimes themselves, the unique modus operandi that sets American-style massacres apart: a single, frustrated man with a gun blowing away as many people as possible. The killers are most white and from middle-class backgrounds, and almost without exception male. In other words, they are often among the more empowered people in their societies, or rather they would be if they were more socially and emotionally secure, and in case after case, the killer’s rage seems to arise from the world’s failure to recognize him as someone worthy of respect and attention. The act, then, whether it involves a man walking around a job site and shooting the people who humiliated him or stalking a bunch of youth campers whose politics he thinks threatens the dominion of the white race, is about power, about finally, for a few thrilling minutes, getting the recognition the killer feels is rightfully his.

Americans tend to see this urge for personal empowerment as universal, but that’s only because we are so deeply immersed in the ocean of our own culture. In this country, by the way we raise our kids, the TV shows we watch, the video games we play, the political ideals we express, even the very clothes we wear, we exalt the individual. We expect to be treated as unique and special, free to act as we please. We demand to be shown respect in the workplace and at the cash register, and if we are white and male, we are told in myriad ways by our culture that this respect is deserved. When we don’t get that respect, we sometimes snap. For most of us this amounts to no more than screaming at a nightclub doorman who won’t let us past the velvet rope, or writing intemperate screeds in the public comment sections of political blogs. Some people, though, those dangerously reclusive men nursing their resentments in their parents’ homes, can one day simply gather up their guns and start shooting.

To recognize how American this form of violence is, think for a minute of the other headline-grabbing mass murderers of our time, the al Qaeda-style terrorists carrying out their martyrdom operations. Al Qaeda bombers use violence to make a political point, but their modus operandi is different from that of Breivik and other politically motivated spree killers. A suicide bomber goes into his operation knowing not only that he is going to die, but that he is going to die first. No turning the tables on the boss at the end of a .45 automatic. No quiet satisfaction of hunting people like vermin. No thrill of playing a video game with live victims. In a suicide bombing, the attacker kills himself along with as many bystanders as possible, in order that others of his kind may someday gain power over the enemy. Both forms of mass murder end with the wholesale slaughter of innocents, but an Al Qaeda-style assault is at root an act of self-abnegation, the obliteration of the self for the imagined greater good of the killer’s community, while Western-style killings are about self-empowerment, the rush of the act itself.

None of this is to suggest that either of these forms of murder is more or less morally bankrupt—murder is murder, no matter the modus operandi—or even that we should stop exporting our free-market democratic ideals. We are right to champion the right of every citizen to liberty and personal dignity, and to offer people the world over the means to attain those goals. But at the same time we need to recognize how those virtues can sound in the mind of an angry, unbalanced man. We must find ways to make clear that these are rights to be earned, by taking part in and contributing to the wider culture, not merely entitlements. Getting rid of dangerous guns is important, but to a certain extent gun-rights activists are right: Guns don’t kill people; people do. We as a society owe it to ourselves and to the world to build a culture that encourages these murderers to emerge from their hidey-holes of culturally reinforced resentments and disarm themselves.