Nikolai Klimontovich

Our series of contemporary Russian literature continues—six months, six stories from some of Russia's best working writers, plus interviews with their authors, all of it sponsored by Powells.com. This month we feature one of Moscow's finest chroniclers.

The London bobbies may have been bored out of their minds this past fortnight if they were posted anywhere in the city other than Olympic Zone. But if you’re looking for Olympic ghost towns, Moscow in 1980 still holds the record. On the eve of those games, Soviet officials took extraordinary measures to clear the “model Communist city“ of any potential spoilers. The capital fled to the countryside. Less salubriously, the psych wards filled up with Moscow’s dreck.

In round two of our Reading Roulette, we bring you Nikolai Klimontovich, a master portrait artist of Moscow at the height of her inertia.

The story below, says Klimontovich, recalls 1957, when another anticipated influx of foreigners into the heart of the Soviet Union prompted “municipal cleansing” measures of the human sort.

Don’t miss the Q&A that follows for more on the Olympics that Moscow both hosted and skipped, and to learn what it took to convince the good people of Moscow to return on the eve of the closing ceremony, in spite of roadblocks, heightened police presence, and a transportation shutdown.

Once again, TMN’s Reading Roulette is being sponsored by Powells.com. This Friday, we’ll randomly select two people from everyone who’s shared this article on Twitter by that point (and name-checked TMN and Powell’s) and award them a $25 Powell’s gift card.

How to Crow Your Head Off

Translation © Kate Cook, 2012. Used with permission.

Grandmother’s love of cats was indirectly the reason for my atrocious handwriting. I was late starting school and missed the first few vital lessons on how to write properly. This is what happened. At the end of July the Tartar caretaker of the Khimki state farm apple orchard shot our ginger cat with his Berdan rifle. Why he did this remains a mystery. The Tartar was not on bad terms with Grandmother and the cat was certainly no threat to the apple harvest. It didn’t even eat mice, only cod fillet. Nor did Tartars, in my day at least, eat cats. It is possible that the caretaker, in his role as protector of the natural kingdom, felt hostile not towards us personally, nor even to cats or cod fillet in particular, but to the animal realm in general, feline included.

The loss of this friend was concealed from me for some time, but I soon realized that Ginger had been dispatched on a long voyage of the Jules Verne type like Captain Nemo. I missed him and kept asking for news of him. Grandmother felt sorry for me and also grieved. Sometimes in the evening behind my screen I heard her tell Mother how clever he was, just like a dog. I couldn’t understand the comparison. Ginger was wonderful, full stop, and he used to sleep on my feet. In an attempt to recover from the loss Grandmother brought home two strays she had found in the street. There was now a strong cat scent in the room. Fish and meat products, rare in those days, began to disappear in the kitchen from under Grandmother’s nose. And I was discovered to have ringworm.

The reaction to ringworm was very strict at that time. If outpatient treatment did not clear it up immediately, the offender was dispatched to a special hospital. I was taken to Sokolniki on the very eve of the momentous day when I should have started school. At the hospital they removed my clothing and dressed me in flannelette hospital uniform, then shaved my head, wrapped it round with paraffin paper that smelled of iodine and popped a hospital cap on top.

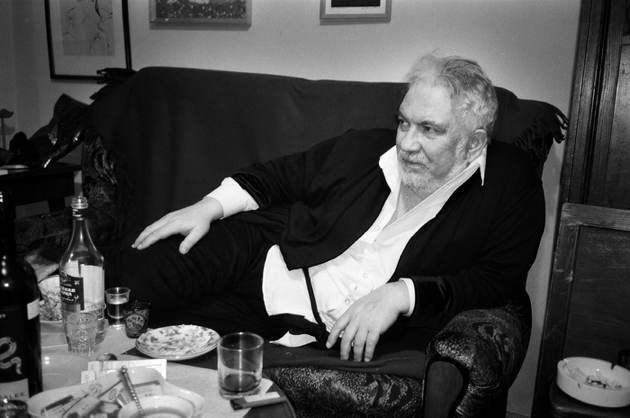

Nikolai Klimontovich was born in 1951. During the Soviet period, he made a living as a journalist, but his prose writing was criticized by Soviet authorities as lacking an “ideological position.” Instead, his work was widely circulated through (underground) samizdat printing. Today, he is equally popular as a novelist, playwright and journalist. His memoiristic novel, The Road to Rome, was nominated for the Russian Booker Prize in 1995.

There were 15 to 20 patients like me in the ward, some with lice. At seven I was probably the youngest, the rest being of school age and overjoyed at this unexpected extension of the school holidays. They were all lads from working-class or peasant backgrounds, quick to use their fists, and there was a prison-type atmosphere in the ward, but no one touched me. They were all too busy squabbling among themselves, punishing anyone who stole from the lockers in the “dark room” and fighting over who should be leader. Strangely enough, given the slightest pretext, the prison atmosphere always seems to assert itself in Russia whatever the situation: in elite holiday homes and boarding schools, orphanages, military barracks, even hospital wards. This type of organization seems to be inherent in the national character. It also matches the structure of everyday life, the coercion, informing, constant shortages, and general ennui.

The sociology in our ward was as follows. Lousy Letuch ruled the roost, a bruiser whose surname was Letuchev, pretty violent and not serving a prison sentence only through some administrative error or because he was underage. His elder brothers, he related proudly, had all done a spell inside. He had a sidekick, a small—even smaller than me—but very strong lad of 11 called Vovan, who did all the dirty work for his boss; sorted out the parcels, beat up the contentious, and generally kept order. The other patients were a motley crew of lawless juveniles, who would have been a close-knit gang of dangerous young adolescents if all this had taking place outside. The only patients not included in this organization were me and eight-year-old Mishka the Jew, as they called him here. Mishka was a quiet Jewish boy from a poor family, brought up at home, as I was. Our position as outsiders naturally formed a bond between us.

There was not much entertainment in the hospital, apart from bedtime stories. No question of television in those days. And no one read books. The only events in our regime were the morning inspection, various medical procedures, four meals a day, visits to the toilet (we used pots under the bed at night), and walks, of course. The pots were emptied by nannies, who always asked Letuch and Vova to help. Vovan carried the shit, while Letuch was team leader. The whole ward knew what was really going on. Letuch and Vova got to smoke in the toilet. Admiring whispers circulated in the ward while they were doing this: Just get a whiff of that tobacco smoke.

The hospital yard where they let us out for fresh air had a high brick wall, very prison-like, except that there was no barbed wire on top. The wall was essential, because the hospital specialized in treating skin diseases and the wall isolated it from the healthy world outside. But that was not the only reason. Behind it stood another medical establishment of a similar kind for the treatment of female venereal diseases. So the syphilitic women shared the wall with us, which had obviously enabled the organizer of this oasis of public health care to economize on building materials and land use.

Whereas our yard was rather bare except for a few stunted bushes and patches of grass, the syphilitic women’s yard had two fine poplar trees with lopped branches. The significance of this fact extended beyond a purely landscapist framework. After lights out, when the doctors left the building and the nannies locked us in, everyone rushed to bag a place on the windowsill and leaned out on their stomachs to watch the performance. For obvious reasons the hospital had been designed so that the children’s ward faced the adjacent building.

When I reached the line “as her body fell down at my feet,” the man with the white coat on his shoulders was heaving convulsively.

It did not get dark until late, so everything was clearly visible. During this pre-twilight hour clusters of masturbators appeared in the poplar trees and the syphilitic women organized a striptease for them. Letuch wanked away happily, finishing on the floor. The rest just shivered. The women probably saw us kids as well, but their main audience were the men in the poplar trees. Mishka and I wanted to have a look too, although we weren’t at all clear what was going on. But they wouldn’t let us near the windows.

All good shows come to an end, if only because darkness was spreading slowly across the September sky and the stars shining through. Letuch collapsed on his bed, satisfied. He had place of honor by the window, of course, and now he began to sing. His repertoire was rather limited, and I can still remember bits of it to this day, particularly as some of these tough romances became classics later. There was “Her braided hair let down,” “The girl from Nagasaki,” and “The ships into our harbor sailed.” But the greatest hit of all was a jazzy dance number called “They roll along like boats at sea…”

Letuch insisted that everyone should join in. Even Mitka and me. After a week I knew the whole repertoire by heart and joined in dutifully. Strangely enough, I felt proud to be accepted into the company of these big daredevil boys, who in this twilight hour seemed to me like the sailors in the songs, dashing and handsome in their lewd coarseness.

On one of these clear September evenings, when the windows were wide open and the women opposite had quieted down and begun to sing something sad and prison-like, I seem to remember, with our ward accompanying lustily, the door suddenly flew open. Everyone stopped singing immediately, except for me who continued blithely.

It was a night inspection, a rare event that never took place more than once a month. The head doctor entered in his white coat, with a couple of younger doctors and a man with a white coat draped over his shoulders. Since my bed was nearest to the door, they stopped and gazed down at me as I went on mouthing:

Then she left me in the lurch

And went off with another,

So your son was abandoned

And heartbroken, mother!

Noticing my high-ranking audience, I stopped, of course, but the man with the white coat draped over his shoulders smiled and said: “Go on, laddy, let’s hear what you’ve got to tell us…” And the ward sniggered happily. Scared stiff, I sang on dutifully:

I often see her lovely face

And beautiful brown eyes,

She’s walking with another man

While I am left here all alone.

The commission’s reaction was a lively one. At first only the man with the white coat over his shoulders chortled, but then the rest followed. I continued as if mesmerized:

I remember that dark autumn night

With rain falling lightly from Heaven

As I walked with you, drunken and haggard,

Singing quietly and thinking of her

Then with fear-inspired, mounting enthusiasm:

In an alley a couple was meeting

And I could not believe my poor eyes

It was she pressed up close to another

And their lips met in sheer paradise.

At this point the doctors began guffawing, digging each other in the ribs. Encouraged by such success, I continued with triumphant fervor:

So I drew out the knife from my pocket

And struck my unfaithful sweetheart

Then ran for my life from the spot

When I reached the line “as her body fell down at my feet,” the man with the white coat on his shoulders was heaving convulsively. My ward companions were also enjoying it greatly, of course. Eventually, the head doctor wiped his eyes and barked: “Silence!” The ward fell silent immediately.

“And you be quiet too, Roberto Loretti,” the doctor said, stroking my paraffin-papered head. I didn’t know who Roberto Loretti was, but felt proud and flattered…

Mishka was beaten up the next day.

Letuchev had a visitor in the morning. It was his elder brother, who had just been let out of prison on amnesty. He brought a parcel of Lyubitelskaya sausage and a bottle of port wine. That evening Letuch and Vovan drank the wine and ran amok. They had to beat someone up, and the most suitable candidate was Mishka the Jew. As if sensing the danger, he tried to hide under the blanket, but as soon as the nannies’ key turned in the lock, Vovan ripped off Mishka’s inadequate protection. While they were beating him, he breathed hard like an old man, lying motionless on his back, with Vovan holding his shoulders down. Tears welled up in his eyes, but did not trickle down. He cried later, when Letuch got tired of his silent victim. Then Mishka covered himself with the blanket and wept quietly without moving. It was this passive acceptance that upset me most of all. Why didn’t he shout and use his fists? I couldn’t help him and this made me feel bad. I was so sorry for Mishka the Jew that I crawled under my blanket and wept too.

When the ringworm cleared up and they discharged me, I took my place in the first form one month late. Everyone but me knew how to dip the sharp nib with a hole in the middle into an inkwell. I had been taught to write some time ago at home, but only with a pencil. I had missed practising those beautiful flourishes for capital letters, at which my classmates were now so proficient. So I got bad marks and was ranked with the dunces. This had certain advantages. It meant I could sit at the back and be classified as a hooligan, particularly as none of my classmates knew the sort of songs I performed in the break. I was the Robertino of the first form (first shift) and quite a celebrity. Since none of the others knew such delightful lyrics, I had no compunction about crowing my head off, and none of my classmates dared to object to me for splitting their eardrums.

It was a lovely warm October and in the break we were allowed onto the school sports ground, which had two net-less volleyball posts. A crowd of pupils from the second to fourth forms also poured in there. And on that sunny autumn day, surrounded by a ring of admirers, yours truly sang. When I got to the line de résistance, a voice called out: Stop that caterwauling, stupid! The voice belonged to a nine-year-old bruiser, taller than me by a head, the spitting image of Letuch, with a couple of Vovans by his side.

“I’m not caterwauling,” I retorted boldly.

“Oh, yes you are,” he said and went for me.

I don’t know what happened, but I suddenly had a vision of poor helpless Mishka being beat up. The memory of him weeping under the blanket was so vivid that I almost burst into tears. I hunched my shoulders, stuck out my head and charged with all my might. My head, now covered with a bristle of short hair, butted my insulter in the stomach, and, probably more from surprise than intention, he kicked me in the chest. I fell headfirst onto a pile of rubble and my nose started to bleed.

“Let’s go, he’s defective,” said my assailant to his gang, meaning that I was nuts, and they retreated glancing back apprehensively. I lay happily in the pile of rubble. I even finished singing my snuffling song through my bloodied nose, which I was nursing with one hand: As her body fell down at my feet. I was still little then and quite unaware of what life held in store for me.

Elizabeth Kiem: Were you present in Moscow for the 1980 Olympics? It’s hard to imagine a “Soviet Casanova” enamored with Western girls would miss such an opportunity to fraternize.

Nikolai Klimontovich: No, I wasn’t in Moscow, precisely because I wanted to avoid a conflict with authorities. During the Olympic Games, Moscow was under the most severe and political and police regime, both for foreigners and Russians. The event was of an entirely official character and the measures undertaken were more likely to provoke wariness than curiosity.

However, I was at the funeral of [the very popular but officially disfavored singer, songwriter, and actor, Vladimir] Vysotsky [who died during the final week of the Moscow Olympics]. There was a huge number of people present, completely taking the authorities by surprise. This show of popular organization probably scared them, having taken extraordinary security measures, including ridding Moscow of all criminal types, banning all intra-city transport, and calling up additional police forces from the provinces.

By the way, this all applies to the era of the story “How To Crow Your Head Off.” Then, in 1957, Moscow hosted the no-less significant international event: The World Youth Festival.

EK: Moscow was a candidate for hosting the 2012 Games. Can you imagine what might have been if you had won? If so, would Pussy Riot and Navalny be on trial this summer?

NK: In the first place, there was no chance that Moscow would win, since the authorities only took it on for their own advertising. Even if it had come to pass, naturally there would not be such draconian measures as under Brezhnev. More likely, it would be a bore. As for these minor political processes that the KGB undertakes out of inertia, they are more likely to amuse the reasonable people of Moscow than frighten them. Navalny and Pussy Riot are fully aware that they’ve gotten themselves in an awkward position. You probably heard what Putin said in London—that the girls would probably not get a harsh sentence.

In the last 30 years Russia has gone through cardinal changes, especially when you consider contemporary youth, who absolutely and organically feel themselves citizens of the free world.

EK: How would you describe the changes Russia has undergone in the three decades spanned by these Olympic Games?

NK: In the last 30 years Russia has gone through cardinal changes, especially when you consider contemporary youth, who absolutely and organically feel themselves citizens of the free world.

EK: Are there contemporary Moscow writers who are as enamored with the quotidian as you were when you wrote of the Brezhnev era? Or does daily life in the Putin era require the fantastical/dystopian treatment that is so popular today?

NK: You are probably right in your assumption. The younger generation of authors is drawn to the grotesque.

EK: What are you writing now?

NK: I’ve been writing a novel for a year now. My latest work is most easily found on the Russian web in The Reader’s Room [section] of the magazine Oktyabr.

EK: And did the kitten ruin your writing forever? Or can you write in cursive now?

NK: I write on a computer.

Nikolai Klimontovich’s The Road to Rome, called “The Soviet Decameron” by the literary magazine Novy Mir, is Klimontovich’s only novel translated into English. Available here, and excerpted here. For readers of Russian, all 20 of his novels and story collections can be found here.