Playing Johnny Ace

A young crooner’s untimely, macabre death left questions for those who would follow—musicians and fans alike. Was it suicide? Was it a hit? A listener's query into one star's place in the history of early rock and roll.

I’ve had the Johnny Ace: Essential Masters collection in rotation for months now. Like an old friend, the balladeer’s soulful croon never fails to bring comfort into the room. Johnny Ace was a suave, sophisticated stylist. His soothing baritone exudes an unusual balance of confidence and vulnerability. Whenever cocktail hour seems like it’s coming to a close, his alluring voice beckons me to fill another glass and stick around.

Nowadays, Johnny Ace is best known for how he died, if he’s remembered at all. Details of that tragic incident vary in credibility, but when I came across these stories a year ago, I had never heard of Johnny Ace. His death led me to his music. Pretty much all accounts agree on the following: Early Christmas morning, in 1954, the 25-year-old superstar shot himself backstage at Houston’s City Auditorium.

Was it a suicide? That’s not clear. Some have even suggested it was foul play. But blues artist Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton was in the dressing room when it happened, and she saw everything. Johnny swilling vodka. Johnny pointing the .22-caliber revolver at others and squeezing the trigger, teasing the stunned onlookers each time the hammer struck an empty chamber. Johnny was a prankster. He got his kicks frightening people with that gun. Sometimes he fired it out of hotel-room windows or at road signs while barreling down the highway in his Oldsmobile. Russian roulette was just another regular gag, but that night in Houston, Big Mama said he had glanced at the weapon, presumably to see where the bullet was, before he shot himself in the head.

Black America mourned. But at the time, most white folks didn’t know who he was. Few had experienced the unhinged, emotional power of passionate ballads like “The Clock” and “Cross My Heart.” They’d never heard him pound the ivories with unbridled intensity as he traded warbling bursts with Big Mama on “Yes, Baby,” a scorching blues-rock original. But the sudden loss of such a rare talent had a harrowing impact on a 15-year-old white kid named David Allan Coe, who was locked in a juvenile reformatory when he first learned that his favorite singer was dead. And nearly 30 years later, while recording his 1981 album Tennessee Whiskey, the country star ruefully recalled the day he heard the distressing news before launching into his own effusive rendering of Ace’s posthumous hit “Pledging My Love,” the song that made Johnny Ace a household name in 1955.

“Pledging My Love” was a musical first. When it became a hit, most rhythm and blues music could be heard only on black radio stations and roadhouse jukeboxes. But “Pledging My Love” crossed over to Billboard magazine’s pop charts, underscoring the song’s popularity with white listeners, and became the first R&B single to win Billboard’s Triple Crown, leading the nation’s urban areas in record sales, radio airplay, and juke-box spins.

“Johnny Ace’s death made ‘Pledging My Love’ a monster hit,” says Grammy Award-winning recording artist Dave Alvin (The Blasters, X, The Knitters) during a recent phone interview from his home in Los Angeles. Last year, Alvin released “Johnny Ace Is Dead,” a hard-hitting rocker that provides the gritty details of the shooting and the days that followed. “In some ways, Johnny Ace’s accidental death might have guaranteed that someone would remember him,” Alvin adds. “Maybe not for his music and his piano playing, but they would remember him for something.”

Those who grew up with him in Memphis remember Johnny Ace as a shy kid who loved the blues, all those songs his father, a pastor, had forbidden him to play at home. Back then he was known as John Marshall Alexander Jr., and every time his parents stepped out of the house, he took advantage of the opportunity to hammer out riffs on the family piano. Like many Beale Street artists in his hometown, Alexander was self-taught, often cutting classes at Booker T. Washington High School to hone his bold percussive style on the band room piano. After dropping out of high school and then getting booted from the Navy, he got a break in 1949 as the pianist for the Beale Streeters, an influential group that included future blues masters Bobby “Blue” Bland and Riley “B.B.” King.

During his downtime, he stole the heart of high-school freshman Lois Jean Palmer, who married him at 16 and carried his child. But Alexander’s sole devotion was to his music. His solution to the burdens of familial commitment was to leave his pregnant wife with his parents while he holed up in Beale Street’s Mitchell Hotel, living off the chili the proprietors gave away to musicians.

“His death, like Hank Williams’s death, was charismatic in that it happened at the right time.”

By 1952, King and Bland had left the Beale Streeters, and Alexander had begun developing his own material with the production assistance of disc jockey David James Mattis, who also owned Duke Records, a fledgling Memphis label.Together, they came up with the stage name “Johnny Ace.” “My Song,” the first tune they recorded, made it to no. 1 on the R&B charts, kicking off an unprecedented rise to stardom.

But fame brought unexpected pressures. Now that he was Johnny Ace, a big-time singer with his own backing band—his own pianist, no less—his confidence wavered. Often, before live performances, he’d succumb to a debilitating stage fright, an obstacle he’d overcome by running off his pianist and taking on those duties so that he could sing from behind the instrument. The piano—that tool that had enabled him to find his own musical voice—now served as a buffer from his adoring fans whenever he lacked the courage to face them.

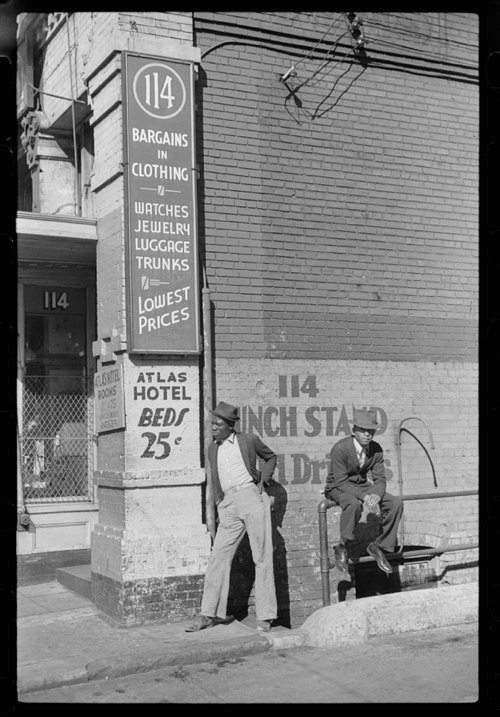

Is Johnny Ace’s gun really in there? a teenage Dave Alvin wonders, his gaze fixed on Big Mama Thornton’s purse as she takes the stage. It’s the early ’70s. Alvin and his brother Phil have slipped from their home in Downey, Calif., and sneaked into a Hollywood dive to catch the legendary chanteuse’s act. Once they’re inside, someone tells them that Ace’s revolver—the one that killed him—now belongs to Thornton and never leaves her side.

“Whether it was true or not, I don’t know,” Alvin says. “But I almost included it in my song [“Johnny Ace is Dead”]. There were lots of stories about Ace’s death—that [Ace’s manager] Don Robey called in a hit on him, that his death was intentional, that it was the Mob. You just heard these things when you’d hang around older musicians.”

The Alvin brothers first learned of Johnny Ace via nighttime broadcasts from border blasters—powerful Mexican radio stations with signals up to 250,000 watts. The R&B shows of famous DJs like Wolfman Jack and Art Laboe could be heard as far away as Alaska, and Alvin says these programs featured “request songs,” making it possible for listeners to dedicate tunes to lovers hundreds of miles away. Ace’s “Pledging My Love” was a popular choice, even in the early 1970s.

“People don’t realize how big Johnny Ace was,” Alvin explains. “Would the history of rhythm and blues and early rock and roll be drastically different if you removed him from the story? Probably not. But his death, like Hank Williams’s death, was charismatic in that it happened at the right time. He’s in that group with James Dean, Hank Williams, and Buddy Holly.”

Bob Dylan, Aretha Franklin, and other luminaries would cover Ace’s songs, but his memory would be kept alive by those artists like Coe and Alvin, who’d remind us of the void left behind by his sudden disappearance from the lives of fans.

And yet most of these tributes are powerful meditations on Ace’s death, rather than celebrations of his small but remarkable body of work. There’s the evocative cinematic rehash of his final living moments in Cowboy Mouth, a play by Sam Shepard and Patti Smith. And then there’s Paul Simon’s brooding rumination “The Late, Great Johnny Ace” which features a youngster who hears of the singer’s death and sends off for his photograph to satisfy an undefined need. Simon’s vignette has profound significance because over the airwaves, the painful loss of the R&B icon resonated with listeners, initiating a flood of requests for photos and long-playing records carrying his hit songs. Most of these demands came from new fans—white folks with the money to buy these things. In later years, we’d witness this same phenomenon after the unexpected deaths of other artists and the subsequent deluge of reissues, remasters, compilations, even the release of personal letters and private journals. Tragedy and martyrdom have marketing potential. And no one understood that better than Don Deadric Robey, Johnny Ace’s manager.

When Johnny Ace left the world with only six hits to his credit, Robey saw an opportunity to keep the cash flowing. He started with Ace’s funeral.

A brilliant businessman with an eye for talent, Robey was the founder of Peacock Records, one of the few lucrative black-owned labels in the early 1950s. Determined to expand his niche in the R&B world, Robey had invested in Mattis’s Duke label, then dumped his partner and shipped the Duke-Peacock enterprise off to Houston. Robey wasn’t a particularly honest person. He had a bad habit of putting his own name on songs he didn’t write and securing the publishing rights to his artists’ material through questionable means. When Johnny Ace left the world with only six hits to his credit, Robey saw an opportunity to keep the cash flowing. He started with Ace’s funeral, working through channels to have the service held in Clayborn Temple, a Memphis church that could seat 2,000 people. Though reports about attendance vary, it’s estimated that a crowd of more than twice that size showed up for the service.

Robey then took his time releasing Ace’s six remaining songs and hired Texas musician Jimmy Lee Land to play the role of Buddy Ace, Johnny’s “brother.” Robey promoted the release of Johnny Ace’s final single, “Still Love You So,” with Buddy Ace’s debut “Back Home” to give his new artist a publicity bump.

The mysterious surfacing in the 1980s of one more long-lost track sparked yet another rethinking of Ace’s legacy. Today, my copy of “I Cried” arrived in the mail, and as I listen to the tune, I’m struck by the choked, granular texture of Ace’s voice, a striking contrast with his signature silky baritone. Two martinis later, I’m still processing his tortured moans and raspy howls. There’s just something about that voice, sounding like it’s rattling though strained rusty pipes, that makes the gin flow faster, initiating a mental slideshow of the half-dozen black-and-white photographs that I’ve seen of Johnny Ace. The radical shift to a grittier vocal style makes “I Cried” a priceless artifact from the mythical singer’s distant past.

But I soon learn that the voice of this vocalist probably doesn’t belong to Johnny Ace. In fact, James M. Salem, the author of The Late Great Johnny Ace, states in his fascinating, scrupulously detailed biography that “no one familiar with Ace’s voice could ever make so preposterous a claim.” To set the record straight, I seek Professor Salem’s contact information, only to find myself reading his obituary.

The uncertainty surrounding the “I Cried” voiceprint is just one more loose end in the Johnny Ace saga, a story that will never provide us the comfort of closure, just the promise of more questions.

As Johnny Ace: Essential Masters slips back into the queue, I settle down on the couch with a fresh drink and soak up the congenial familiarity of the balladeer’s voice. His songs were with me for all of 2012, and I’m certain they’ll be accompanying me through crowded supermarket aisles, traffic jams, and hours of solitary brooding well into the future.