Rainy Night in Georgia

Even in the most forsaken corners of the Caucasus, daily life can boil down to domestic turmoil, hip-hop videos, and arguing over Bryan Adams’s nationality.

There is no such thing as a scheduled departure time in the former Soviet Republic of Georgia. After a home stay with a family in Tbilisi, I arrived at the Didube station and bazaar one morning a little hungover and asked a driver when the next mini-bus would depart for the Caucasus mountain outpost of Kazbegi.

I had recently quit my job in Chicago, leaving behind a girlfriend to travel for several months along the Silk Road. I wasn’t a holidaymaker or a businessman. I had no urgent need to reach my destination. My goals for the trip and in life were vague, and I had no idea I was about to experience a night of bed, breakfast, and drunken threats in a place that doesn’t appear on most maps.

“Ten minutes,” the man said, not very convincingly.

As it turned out, “10 minutes” in Georgia actually meant: as soon as the bus is beyond what any reasonable person would consider hazardously full. I would have to wait.

The Didube bus terminal was a thriving marketplace where one could see Georgia’s struggling entrepreneurial class. Tough-looking senior citizens from the countryside sold produce out of the trunks of dilapidated Soviet-era cars. Drivers called out the names of destinations.

“Gori! Kazbegi! Batumi! Rustavi! Zugdidi! Kutaisi!”

All the places seemed to rhyme, and if you had enough patience you could get just about anywhere for a few Georgian lari. Our tottering old minibus finally pulled out, slaloming around vendors and shoppers, 80 minutes after the initial 10 minutes had passed. As we sputtered up the Georgian Military Highway, passengers wordlessly hopped on and off the bus, never discussing price.

A month before, I’d spent my days cowering in a cubicle in a soulless suburb near Chicago’s O’Hare airport, hoping my superiors didn’t notice my heart wasn’t in the job. Now I was in a forsaken outpost in the Caucasus arguing about Bryan Adams’s nationality.

An hour or so outside Tbilisi, as the snowcapped Caucasus came into view on the horizon, the road began to deteriorate. There were boulders and potholes almost as large as our minibus that gave the road an apocalyptic, end-of-the-world feel.

At first, I’d found it hard to believe that a five-hour ride to Kazbegi cost only 6 lari ($3). But I felt every bump in the apocalyptic road, and my legs tingled from the exertion of trying to maintain some semblance of personal space. In the Caucasus, bargains are relative to one’s threshold for discomfort. The road to Kazbegi is closed in the winter, leaving residents of the forlorn north cut off from the world for the season.

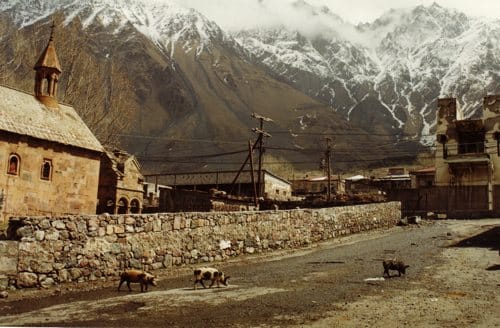

Despite the majestic alpine scenery, Kazbegi didn’t make much of a first impression. My five-year-old guidebook indicated there was a hotel in town, but where? The village was dead, but for a collection of unsupervised, mud-splattered farm animals roaming the abandoned streets.

Who was it that had recommended this place? I couldn’t recall. I approached three men smoking homemade-looking cigarettes who appeared to be the only people around.

“Hotel Kazbegi?” I asked, with a shrug of my shoulders.

They shook their heads. One of the men extended his arms out like a baseball umpire calling safe. The Hotel Kazbegi was deader than Stalin. With no ability to speak Georgian and just a few Russian phrases at my fingertips, I was reduced to “me Tonto” diction.

“Other hotel,” I said. “Any hotel.” The rain picked up.

“No hotel. House. Me. Come,” said an unshaven man, whom I later learned was named Georgi, who was sitting in a decrepit old car parked next to the three men seated on a bench.

I had no umbrella or better ideas, so I hopped in his car.

“You American?” he asked.

“Yes,” I responded.

“Look, American moozic,” he said, popping the Bryan Adams cassette Reckless into a tape deck that was duck-taped into the dashboard.

“I’m findin’ it hard to believe we’re in heaven,” Adams crooned as we barreled through the shabby village en route to Georgi’s home.

“You like American moozic?” he asked, reminding me of the Violent Femmes song. (“We like all kinds of moozic.”)

“Actually, Bryan Adams is Canadian,” I said. I was desperate to disown one of North America’s cheesiest recording stars, whose insidiously catchy melodies had apparently penetrated even this little village hidden deep in the Caucasus mountains.

“American!” he insisted, holding up the tape case for my inspection, as though I had called into question the quality of his recording.

A month before, March 2000, I’d spent my days cowering in a cubicle in a soulless suburb near Chicago’s O’Hare airport, hoping my superiors didn’t notice my heart wasn’t in the job. Now I was in a forsaken outpost in the Caucasus arguing about Bryan Adams’s nationality.

We arrived at Georgi’s home a minute later. After we settled on a price of $5 for the night, Georgi honked the horn, shouted something to his wife, and sped off with my five bucks. His wife, Nonna, came out to greet me with her two little boys, whom she introduced as Gogga and Ruslan.

The family home had a vestibule area that functioned as a shop, with items for sale such as detergent, chocolate, and long life milk, alongside children’s sticker books and pencils. Nonna had a thick mane of curly black hair and a dimpled smile; I took her to be in her early thirties.

She spoke no English, but was warm and friendly. After inviting me in, she brought me a cup of tea and a coffee table book entitled Soviet Georgia 1921–1981 with text in both Russian and English. The tattered old tome was filled with amusing Soviet takes on Georgian history.

“Toward the 18th century, when Georgia was under threat of genocide, Russia was there to stave off the danger!”

But there was also some truth mixed in with the bullshit, including an interesting section on the legendary tradition of Georgian hospitality. “We can inevitably conclude that history itself has taught people which suffered much cruelty and ruthlessness to appreciate every sign of friendship and be ready to lend a helping hand.”

The rain continued to pour down outside, and I resigned myself to spending the afternoon in their home. But I hadn’t been shown to a bedroom, so I couldn’t very well curl up with a good book. Then Gogga and Ruslan’s young cousin came over and the four of us played a spirited game of keep-away with a big ball for an hour until we were exhausted.

I’d picked up a placemat from the country’s only McDonald’s in Tbilisi. I was struck by how beautiful the distinctive Georgian script looked on the familiar logo. I showed it to the boys. They had never even heard of McDonald’s before, and I found myself wishing that I could treat them to a Happy Meal.

Nonna brought out a pair of slippers for me to wear and showed me a photo of her wedding day in which little Gogga was present in the background. As I pondered the circumstances that had conspired to bring Nonna and Georgi together, the man himself barged in. He stood, swaying underneath an archway leading to the living room, with glassy, unfocused eyes. It only took a moment to realize that Georgi was piss drunk, trying to identify the strange man sitting next to his wife. He came closer and shouted something. Nonna let out a sheepish laugh. Emboldened, he stepped closer, shouting, slurring his words, before crouching down to about a centimeter from my face. He looked down at my slippers and muttered something.

Nonna berated Georgi for a moment in Georgian until he half-jumped up from the table and raised his hand as though he was about to strike her. No one said a word.

Was I wearing his slippers? Had I been sitting too close to his wife? He reacted as though he had no recollection of picking me up only a few hours before.

I stood up and shouted, “Georgi!” hoping to jog his memory, or at least remind him of my height advantage. But he kept shouting and jabbed a hard, dirty finger into my chest to emphasize his point. He had obviously spent the five bucks I’d paid him on booze.

“Bryan Adams, remember, no Hotel Kazbegi!” I said.

Nonna yelled at him, clearly embarrassed but not surprised by the outburst.

“I’m going out for a walk,” I announced.

The great outdoors provided little respite. The rain kept falling, soaking the dismal village in a merciless muck. Shopping for dinner in town took two minutes. All I could find were sticks of pinkish looking meat that might have been baloney.

I thought about leaving town, but the only way out was the minibus I came in on and it wouldn’t leave until late the next day. I was stuck with Nonna and Georgi. For one night, their home, their problems and their world were mine too.

Back at the house, Georgi made too strong an attempt at reconciliation.

“David, come here, moozic.” He beckoned me into their TV room to watch, of all things, American gangsta rap videos with him.

“American moozic good?”

I ignored him.

“Good?” he persisted.

“Yes, American music is good,” I conceded, like a schoolboy reciting his lessons.

The whole family stared intently at the little TV, filled with images of young bejeweled black men surrounded by scantily clad buxom blondes.

“David, American girls good?”

I actually didn’t understand—his speech was slurred—until he stood up, went over to the TV, and pointed at the chest of a young girl to clarify his point.

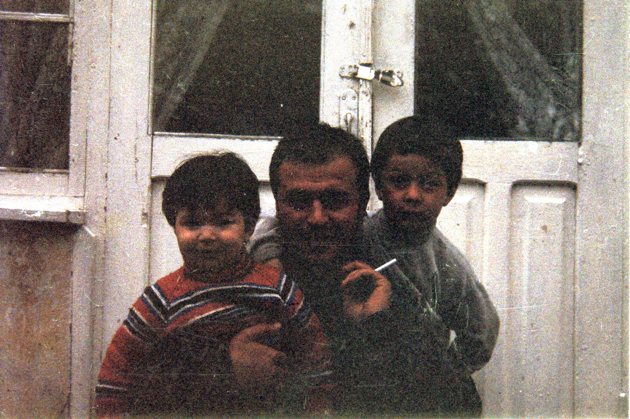

Georgi later saw my camera and insisted on dragging his boys outside in the rain for a photo-op. I told him the photo wouldn’t turn out, and Nonna tried to dissuade him, but he pushed her away and insisted that I take a shot of him and his boys in the rain. Mercifully, Nonna called us to dinner, into a drafty, dark little outbuilding behind the house that served as their kitchen and dining room.

Georgi devoured his chicken and potato dinner without benefit of cutlery or a napkin, only occasionally looking up from the carnage to pound his fist and make an arcane proclamation. His sons devoured the mystery baloney I bought as if it was the finest meal they’d ever tasted. I complimented Georgi on his sons. He was having none of it.

“Him good!” he said, tousling Ruslan’s head with his greasy fingers. “Him, aaaagggh,” he exclaimed, gesturing to indicate that Gogga was a wimp. Gogga slumped in his chair, cast his eyes on his empty plate in silence. Nonna berated Georgi for a moment in Georgian until he half-jumped up from the table and raised his hand as though he was about to strike her. No one said a word. Georgi trembled in a drunken rage as a morsel of food fell out of the corner of his mouth.

In that moment, I decided that if he hit her, I was going to hit him and it would be a hot time in the old town of Kazbegi that night. Luckily, he soon repaired to another room, where he no doubt passed out in a puddle of his own piss and vomit.

After dinner, Nonna’s brother stopped by, and I was delighted to learn that he spoke some English. While Nonna did the dishes, he gave me the skinny on their unfortunate relationship.

“You see, Georgi likes to drink,” he said. “You must ignore him. He’s young, he will learn.”

“Young?” I said. “How old is he?”

“He is 25. Nonna is only 24.”

I was speechless; they were both younger than I was.

“They were very young when they married,” he said. “My sister was only 17.”

He shrugged his shoulders, gave me a knowing half-smile, and let the situation speak for itself. How could she have known what a drunken asshole he’d turn out to be? And what was she supposed to do after giving birth to a child with him?

I had been reading Essad Bey’s book, 12 Secrets of the Caucasus, published in English in 1931, which explains wedding rituals, specifically the kalym, or dowry paid to the bride’s family.

The height of the prices has always varied in direct proportion to the wealth of the man and the beauty of the woman. Girls were divided into several groups: ugly, average, beautiful, very beautiful, and exceptionally beautiful, and also into virgin, semi-virgin, and no longer virgin. The classification of a girl is decided upon by a committee of experts and endorsed by the authorities. The price varies from (the equivalent of) $125 to $500 for virgins to a few cents, nominal charge, for those no longer virgins. The lowest price for a virgin is $125, everything above that is considered an extra bonus for beauty. Payment by installations has always been permitted.

After Nonna finished washing the dishes, she insisted I take their master bedroom as the whole rest of the family—including the passed out Georgi—slept in one double bed in the front room.

The next morning, the sun came out and Georgi was blessedly nowhere to be seen. I hiked for hours all around the little town, reveling in the alpine scenery, if not the nasty shepherds’ dogs that menaced me. The natural splendor and the warmth of the sun had me thinking I’d spend another night with Nonna and Georgi, but I soon thought better of it. My holiday in Kazbegi was over.

I bought some meager gifts in town for the boys and returned to the house to say goodbye. Nona seemed disappointed I was leaving. It was unclear if she was under the impression that I planned to stay longer. I felt bad about leaving, but that was the risk of a home stay in a very alien culture—you’re exposed to situations you cannot begin to solve, and the weight of those problems makes your experience seem frivolous, almost perverse. Later that night, I’d be in another part of Georgia. The next week, I’d be off to another country. Moving, moving, moving while Nonna dealt with a petty tyrant she was stuck with in a dead-end town. Or maybe I’d misread the situation and she was content, or at least resigned to her fate. I had no idea. More than a decade later, I’m married to the woman who waited for me to return from my Silk Road adventure, and we have two little boys who are the same age as Gogga and Ruslan when I met them. Once in a while, if I lose my temper with my boys over some trifling matter, I think about Georgi and remember that I don’t want to be like him.

Before leaving Kazbegi, I slipped Nonna some cash. She accepted it without ceremony. My gesture felt inadequate and awkward, but I had nothing else to offer. I sat waiting in the town square for my minibus, and watched a drunken old man hassle the kiosk owners who refused to sell him beer. I wondered why that sort of community policing hadn’t worked on Georgi.

Right on cue, he came into view walking toward his home. He didn’t see me and I began to indulge in a few moments of fantasy. I would jump him from behind, beat him senseless, then take his family back to Tbilisi with me. In the movie version of his story that’s what would have happened. In reality, I did nothing more than wait for my bus and hope Georgi wouldn’t drink away the money I’d given his wife.