Remnants of the Underground Railroad

The Thirteenth Amendment passed 150 years ago, abolishing slavery. Today, little of the Underground Railroad still remains. A painter hits the road to discover what’s intact.

“Here was the home of William Maxon, a station on the Underground Railroad,” the plaque read, “where John Brown of Osawatomie recruited and trained eleven men for the attack on Harpers Ferry.”

John Brown believed that only through an armed insurrection could the country be purged of slavery. In the 1850s, the expanding west, now Midwest, was embroiled in a fight over which new states would allow slavery and which would not. Brown, a New Englander, had come to Iowa after a firefight with Missourians to defend a Free State settlement in Osawatomie, Kan. In 1859, nine years after the divisive Fugitive Slave Act passed, he attempted to enact that plan, seizing a Federal arsenal in Harpers Ferry, Va. Brown was defeated at Harpers Ferry by the man who would later lead the Confederate army: Robert E. Lee. Brown was captured and hung.

I’d been told about the plaque—at the end of a perfectly straight dirt road—by a park ranger at the Herbert Hoover National Park, a few miles south. It had been installed in 1924 by the Iowa Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Mounted on a small boulder at the foot of a tall buttonball tree, the plaque was partly obscured by overgrown grass and a few miniature American flags that other visitors had placed there. I later read that the house mentioned in the inscription had fallen into decline by the 1930s and was torn down in 1938. The tree and plaque were crowded between a dirt road and a farm machinery shed.

“There’s not much else out there,” the park ranger had said. “The Maxon house was destroyed a long time ago.” A tractor and giant marshmallows of shrink-wrapped hay sat by a cattle feeding trough.

I’ve lived in Iowa for three years now. There’s something about Iowa’s farmhouses, so far apart to make room for the vast cornfields, that makes me think isolation is embedded in the land. You need to get off Interstate 80 and start down one of those dirt roads—dipping only when crossing streams—to see the farms. Everyone I rope into a long drive inevitably asks, “Can you imagine living out here—like a hundred years ago?” I know what they mean: no hospitals; no real neighbors; no TV; snowdrifts up to the gutters. Prairie fires, roaring 40 feet high, traveled at 70 miles per hour. The farmers might have been German or Swedish, might have longed for a country and landscape their children never knew or could picture. Here, in eastern Iowa, around Iowa City and Springdale, most of the farmers were Quakers. They believed that God was within every person, and so were pacifists and abolitionists. Not the safer abolitionism of Philadelphia or Boston—those march-in-the-street abolitionists. They were the kind whose commitment was tested when escaped slaves, running away from Missouri, arrived at their doors asking to be hidden.

It was the absence of the Maxon house noted in the John Brown plaque that got me started. I’d never considered the Midwest’s role in the Underground Railroad, and wanted to know more about Brown’s time in this part of the state—the part curling its back importantly against the Mississippi River. I decided I’d take photographs to document what I could find of the eastern Iowa’s Underground Railroad, which, if the missing Maxon house was any indication, looked to be passing away, if not altogether gone. I would find all the old safe houses I could.

This year marks the 150th anniversary of when the United States Senate passed the Thirteenth Amendment, in 1864, which abolished “slavery and involuntary servitude.” At the time, Iowa was sympathetic to the abolitionist movement, unlike its southern neighbor, Missouri. It was America’s western-most free state, and crucial for slaves escaping the Missouri farms. Iowans outfitted their houses with crawlspaces, tunnels leading away from cellars, and, in the case of one house in Salem, Iowa, a floor that lifted to reveal a stairway down to a secret room. After the Fugitive Slave Act had passed in 1850, farmers helping escaped slaves were sued. Penalties included fines of $1,000 per slave and possible jail time. Whites who armed slaves could be executed. In one case, a few Iowans were ordered to pay a Missouri farmer a quarter-million dollars in today’s currency. There was violence, too, like when a group of Missourians toted a cannon up to an Iowa farm and aimed it at the house of a family refusing to turn over escaped slaves.

To find where the safe houses had been, I first followed the points on a flawed map of eastern Iowa’s Underground Railroad provided by the Herbert Hoover Museum. The map was so inaccurate that I threw it out and teamed up with local historians to find where the houses might have stood. Matching old journal entries and documented “conductors” of the Underground Railroad with county plat maps led us to five sites.

I didn’t find much. With photocopies of the plat maps in my pocket, I’d arrive at a site only to see an empty, snowy field. In one case, a little-league field had been built on the foundation of a house that had been outfitted with a tunnel that ran a couple hundred feet from its basement to a neighbor’s basement.

I found the house in West Branch, Iowa, where John Brown had spent a few nights in 1856, only to see that the interior had been redone so thoroughly that the only trace of a 19th-century home was the shorter doorways. It was a boxy whitewashed house that had a corrugated metal roof garage stretching into the driveway.

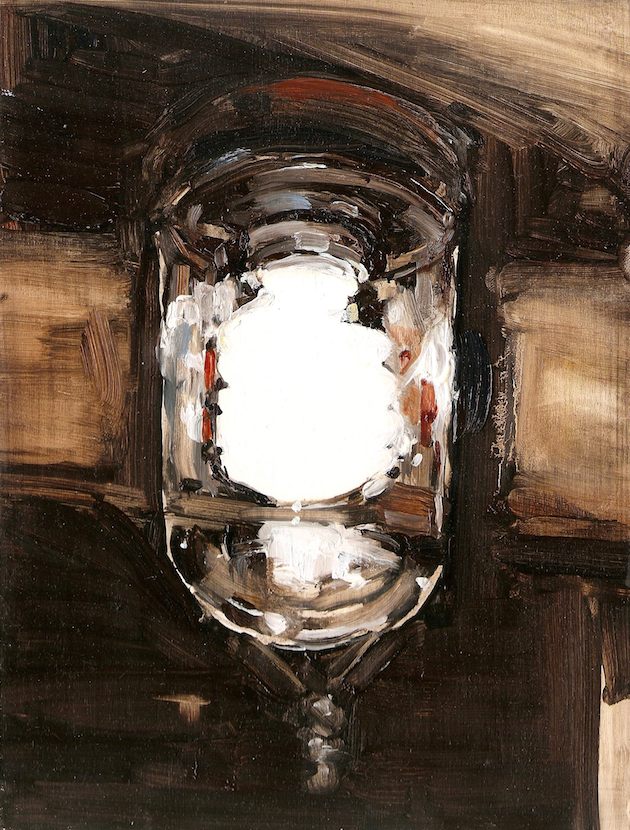

I took pictures of where I went, and at the end of the day would look through images of a field where a house had been, or a pasture of grazing cattle where a barn once stood. It was then, looking through photographs of nothing, when I knew I should be memorializing these sites with paintings.

Painting has always been a part of my life—my dad is a painter, the smell of turpentine still makes me nostalgic. I’d been showing work in galleries since college, but these paintings would for the first time use narrative in a way I’d only done in fiction writing. It was the emptiness, the haunted absence of buildings, that needed to be memorialized in a way more time-consuming than snapping photographs. I wanted to pay tribute to those Quaker farmers and their disappeared homes with the same devotion that, say, early Dutch painters had looked on land reclaimed from the sea.

An employee at the Cedar County Historical Society and I made a great discovery: Samuel Yule’s barn. Yule had written in his journal on Oct. 30, 1853, that “Three men were at my house that ran away from Missouri. Hid all day in the barn, got supper and James Cousins took them to Fairview, Jones County.” The State Historical Society of Iowa knew of Yule’s barn, but assumed it was long ago demolished. The Cedar County plat map I had showed that the Yules lived on what is now Department of Conservation land. On a late April day I walked far into the woods to find a dilapidated barn, hemmed in by forest and covered with vines. We found a picture of Yule’s barn from the early 1900s and matched it with the one decaying in the woods.

American slavery is hard to understand in its profoundly immoral and malevolent definition, but standing in front of Yule’s barn I saw an entry point. Right here, inside these weatherworn walls, three abused men hid on a late October day, 163 years ago. Another man brought them food. If I were an Iowan farmer, if I were Samuel Yule, would I risk my land and house to hide these men?

If three men came to your house before sunrise and asked to be hidden for one day, would you do it, even if it possibly meant jail time and being fined $90,000?

Traces of those early Quaker abolitionists are still present in eastern Iowa, though their houses are gone. Down in West Branch, a few miles south of the Maxon plaque, I met Tim Crew, the great-great-grandson of Ruthanna Coppock, whose young cousins, Edwin and Barclay, went with John Brown to Harpers Ferry to capture the arsenal to begin their armed slave revolt. Of the 21 raiders, only four escaped and were never captured—the rest were killed, or captured and hung.

Crew owns the sheep farm where a safe house used to stand. In his barn, he told me that “When the Coppock brothers got captured at Harpers Ferry, one of them managed to escape and made it back home. But the other one didn’t. He hung with John Brown and the rest of the troops that hung out there.” Crews eyes fell, as if the pain of the execution were still acute, as if the deep past were still present.

Ben Shattuck’s paintings of Iowa are currently on view at The Harrison Gallery, Williamstown, Mass., through June 30, 2014.