The Bull Passes Through

Every summer, many are injured when bulls run the streets in Spain. A report from inside one man’s skull before the rocket goes off.

Dan is in, Brian is out, and I suppose I am 51 percent in and 49 percent out. I am going with Dan into a walled-off, maybe 25-foot wide street. People above us, in positions of safety, gaze down with looks of concern.

“Give me your stuff,” Brian says, and Dan and I empty our pockets and hand him our sunglasses.

I keep my credit card, my driver’s license, 50 euros cash, and my insurance card in the buttoned back pocket of my white linen pants. We shake hands and he pats us on the back. We don’t try to convince him to reconsider because this is not the kind of thing you can fault someone for skipping. And if we convince him to do it and he gets hurt, we have to pay a doctor to fix him and a therapist to fix us.

“See you outside the stadium at the ticket window,” I say, and turn and walk into one of the more famously dangerous places to be on July 7 every year.

The faces of people down here with us tell a story much more pertinent to my situation. Some look fast, well prepared, dressed almost exclusively in white with red accessories—neckerchiefs and shawls in San Fermín tradition. Some look drunk, like they haven’t been to bed since this 204-hour party started 19 hours ago; many of them will be thrown out of the route by the policía before 8 a.m. We fall somewhere between. We are not drunk, but our white clothes are soaked in red sangria from the opening ceremonies. We went to bed early, but did not sleep well and do not feel well. If we were still 22 we’d be drunk.

Dan is very fast. I think I am probably faster than most of the people down here. But after speaking to people in this town for the past 36 hours, I’ve gathered speed doesn’t much matter. This is not a race. No one is PR-ing today. No one is qualifying for Boston. Speed doesn’t much matter because something like a dozen bulls are being released at the sound of a rocket, and they are going to catch whomever they want.

We walked the course the night we arrived in Pamplona. We are now on Day 12 of a 13-day, mostly sleepless trip to Italy and Spain. It is 7:15 a.m. on Saturday, July 7—the first day of the Running of the Bulls. Because it is the first day and it falls on a weekend this year, the route is crowded with spectators and runners. We fly home to Chicago tomorrow from Madrid, assuming there are no overnight hospital stays.

In 45 minutes, those bulls, weighing something like a thousand pounds each, are going to come charging after me and every other person on this cobblestone road who feel the need to put their life in arbitrary danger. Until then it is going to be a long wait, and I imagine an even longer five-minute run down this 848-meter stretch of narrow, enclosed road that more closely resembles the sidewalks and alleys I’m used to in the United States. This is particularly scary for me because before Thursday night, the biggest bull I’d ever seen was Bill Wennington.

It’s a fact: people are going to get hurt. It happens every year. People are gored, thrown, trampled by humans, trampled by bulls. Sometimes people die, though no one has been killed running since 1995, according to Dan[[1]]. People down here with Dan and me are hugging, saying good luck in Spanish and English and Aussie English, trying to stay positive with each other, but looking at friends with faces that say something serious. According to the locals I’ve spoken to, most of the people who get hurt are foreigners—most of them don’t know what to do.

“One last thing,” I say to Dan. “Let’s agree that neither of us should feel pressured to do this just because the other is. This is an individual choice. Neither of us hassled Brian and for good reason. Don’t feel like you have to be here because I’m here, and I’m not going to feel like I have to because you’re here. We still have time to get the hell out.”

Dan nods his head. I honestly don’t think he has reconsidered this since we booked our trip two months ago. If he is scared, it isn’t showing.

“I’m doing it,” he says. “I’m here. I’m doing it. I have to.”

For the last few months, I legitimized running with the bulls by telling people I played soccer in high school and am generally faster than most people. One hundred percent of the people I said this to laughed. Somehow they knew already that speed is going to be as valid as spandex on a bike n’ brew.

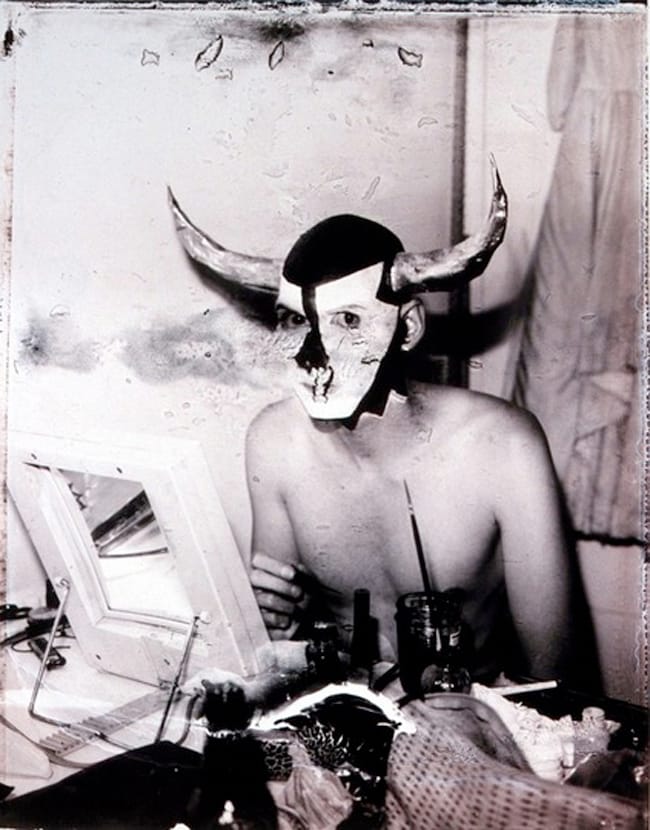

A television camera is panning across our faces as we speak. I try to hide the worry. I think about my mom. I think about my family together at our cabin in the Wisconsin Northwoods, fishing, skiing, playing the Rolling Stones, safe, worried. I sat up all night in our hotel room while Dan and Brian slept last night, all of us in the same bed, and I still can’t tell if I’m doing this as one last adventure before I make a serious attempt at settling down or if I’m doing this because this is what I’m turning into: a true model of self-destruction.

I wrote my mom an email last night saying I was scared and I loved my family. I lay awake all night wondering if this was my last night of sleep—turns out that question made it impossible to sleep at all.

“In situations like this,” I say, “I always get the feeling that if someone is going to get hurt, it’s going to be me.”

“Why’s that?” Dan asks.

“I supposed because I’m always the one who gets hurt.”

We’ve done some stupid things on this trip. In Cinque Terre we jumped off rocks into the sea at two in the morning after watching Italy beat Germany in the Euro semifinals. In Barcelona, I got robbed on the way back to our apartment at four in the morning, and we all got molested by prostitutes afterward.

We came to Pamplona on a bus Thursday and went to a bullfight. I don’t agree with Hemingway. I don’t know much about bullfighting, and maybe it was different in 1923, but from what I witnessed Thursday night, I think matadors are bedazzled cowards. They stack the deck like a Vegas house stacks slot odds. It is a spectacle of disingenuous sacrifice driven by tradition and profit. The bull is half-dead, tired, maimed, and there against its will. The matador is armed, which I suppose is understandable when facing a bull, but there’s also a group of other matadors ready to jump in and divert the bull from a deadly attack.

But on this street right now, those advantages have flipped. We have numbers, but too many numbers—numbers that will force us into uncomfortable places we don’t want to be where bulls are likely to find us. The locals told us this yesterday. One pretty Spanish girl and her grandmother spent an hour trying to talk us out of it. They, along with others back in Madrid, succeeded with Brian. The girl, Cindy, said at least 50 times in her Spanish accent, Don’t do eet, and Do not raan a hundred. When I refused to give in, her grandmother, who didn’t speak a word of English and hated Dan, just shook her head, grabbed my sticky, sangria-soaked cheeks with her wrinkled hands, and kissed me on the lips before she left. Before the trip, I had only gone up in age three years. Now I have gone up 50.

“If you could do it again, would you do anything differently?” Dan asks.

“Today or in life or on this trip?”

“Any.”

I think for a quick moment about plenty of things that apply in my life and give a bland reply, “Nothing major. You?”

“I never would have gotten a dog with the ex,” Dan says. “I loved that dog, but after our relationship ended, it caused us so many unnecessary problems. Don’t get a dog before you get a ring.”

I think about my ex as well and the things I would do differently now that might have put us on a different path, a path that wouldn’t have me on a street this morning with bulls.

More people have gathered in from the bottom of the street, more people leave our area and walk farther up the road. And then a man passes out standing, angling forward without his knees buckling, and lands square on the side of his face on the street. The thud sounds like someone threw a 150-pound piece of clay from five stories up. People rush to him and call for a doctor. They turn him over. His face is covered in blood and he is unconscious. A doctor arrives and tries to wake him. Paramedics follow with a stretcher. We watch as they take him away. He will not be running with the bulls, but he will be among the injured.

The bulls come next to me, not at me, their momentum carries them left, and they are the biggest mass of living matter I have ever seen.

We talk about our plan of action one last time. We remind each other to stay to the inside on the turns. We remind each other that the most important thing is to keep our center of gravity so we stay on our feet.

“If you lose a shoe, keep going,” Dan says.

“Yeah, glass in your foot is better than being trampled—by people or bulls.”

“If you fall, don’t try to get up. Just cover your head and roll to the side.”

“And if you see a bull on its own, try to get out.”

This last point may be the most important in terms of living and dying. From what we’ve been told, bulls together are not as frightened as bulls alone. Bulls together tend to stay on a path, assuming they keep their footing. Frightened bulls directly charge people. If we see a bull alone, we will try to escape by climbing one of the wood fences. We climbed them yesterday. It can be done quick, but the problem now is there are so many spectators lining the street that you’d have the same success climbing them as jumping through the horizontal gaps between the beams.

“Sorry for calling you a douche in Madrid,” Dan says.

“Thanks for calling me a douche in Madrid,” I say. “I deserved it.”

He laughs because he knows I deserved it, but I imagine he wants to clear the air in case I end up with a gore hole.

I wrote my mom an email last night saying I was scared and I loved my family. I lay awake all night wondering if this was my last night of sleep—turns out that question made it impossible to sleep at all. I wondered if I would be injured to the point I wouldn’t be able to have children. I thought about everything being different after today—different in a very bad way. But here I am. I know I’m being selfish. I know people are worried about me, and that comforts me, and that is selfish, too.

“I think,” I say, “it’s less about what I would do differently than what I want to do differently when this is over.”

“How so?” Dan says.

“You know—living like this,” I say, my hands open to my sangria-soaked shirt, and that’s when it all comes out: “It has to end at some point. I want to try harder after this. Chill the fuck out some when we get home. I’m tired. I have been for a while. Maybe try to have a girlfriend again. Find a new job. You know—we’ve talked about this so many times and we just never do it.”

“Yeah,” he starts. “I realized that about my job when we were walking around Madrid the other day. I’m just not sure what to change that would change anything significantly. You have your writing, your book. You have something you’re enthusiastic about. Me? I’m not sure.”

A man comes by handing out newsletter-sized papers. From what I can make out, it is a benediction to the city’s patron saint, Fermín. Fermín is the star of this show.

“See you in the stadium hopefully,” I say.

“See you in the stadium,” Dan says.

We smile and hug, pat each other on the back. We have done this man-hug thing a number of times in the last few years on a number of adventures, but never with such a feeling of potential harm.

The man finishes handing out the papers. People roll them up, raise them above their heads and chant, Spanish followed by Basque:

A San Fermín pedimos, por ser nuestro patrón, nos guíe en el encierro dándonos su bendición.

Entzun arren San Fermín zu zaitugu patroi, zuzendu gure oinak entzierro hontan otoi.

VIVA SAN FERMÍN

GORA SAN FERMÍN

“There’s no shame in pissing yourself in the next five minutes,” a British man says behind me.

I laugh and turn.

“I was just thinking the exact same thing.”

“Good luck, man,” he says.

“Good—”

The rocket fires and the crowd erupts with the sound of carnage you’d expect when enemy sides charge each other, but only one of them carries weapons.

Everyone’s first move is forward and two guys go down. No one knows what to do but nearly everyone is looking over their inside shoulder, shuffling their feet with uncertainty. A few people start to climb. A few others try to move forward and jam themselves under the wood fences that separate intelligence from stupidity.

People book it forward. Dan passes a few guys and I don’t bother to follow him directly. A guy to my left goes down and I don’t bother to look back over my outside shoulder to see if he is okay. There is no going back at any time.

I look over my inside shoulder to make sure the bulls aren’t yet coming, and then look forward to get my sense of direction on the course figured out. I stop moving forward so quickly because I don’t want to get to the next turn in the position I currently have in the crowd—I know I need to move right before the road goes right—always be on the inside. The bulls come with such force, I’ve been told, that they cannot turn the corners on the unforgiving cobblestone and often slip up. You do not want to be between a sliding bull and a brick wall. But I am afraid to run across the middle of the street. It is only a 10-foot space, but it is a 10-foot space that will soon be occupied by the first pack of bulls.

I fucking sprint like you can only sprint when you are sprinting from danger, I sprint with fucking urgency.

I keep running forward—fuck—and I’m still on the left side when the turn approaches.

Fuck I need to fucking get across.

I’m on the outside.

I look over my right shoulder, don’t see any bulls but the volume is rising, and I sprint across, dodging people coming up the middle, to the right where people are jammed along the wall. I start to run past the crowd, then fight the first instinct to keep passing them and jam myself into them. I throw myself into the wall of other runners—five feet deep against the wall, moving forward slowly, but I don’t get in. I think I am far enough over, but I do not have anyone protecting me.

“Here they are!” someone yells from behind and the faces I see across the street look like faces I imagine in combat without any cover. I don’t see the bulls but I know those guys do and I know they are fucking close. I keep my back to the wall so if one comes at me I can react as quickly as possible. But there is nowhere to go. It is a mass of people within a mass of people within the mass of people flooding this city. If a bull comes at me it will do what it wants to me. I keep pushing myself on a diagonal—right and forward—and hope the bulls take a wide turn and no one pushes me out.

And then bulls are coming behind me, I push, I fucking push three bulls across the front, I actually don’t know how many total.

They look loud but the human noise overtakes theirs.

More bulls—fucking huge animals—in the back.

Everyone yells, people scream, duck their heads into their arms, people dive out of the middle, people dive to my feet and scurry forward, people dive right in front of the fucking bulls—they are here, huge, huge bulls charging, here they are, just don’t gore me—throw me, break my arm, knock me down, just don’t gore me.

The bulls come next to me, not at me, and their momentum carries them left, and they are the biggest mass of living matter I have ever seen, some black, some lighter brown. If they get scared, if something sets one of them off, it will try to kill me. There is nowhere to go. If one of them decides to charge this crowd, it could gore many. It could turn our white clothes much redder than the sangria. The horns look like they could go through me and whoever is behind me and maybe a third. Two feet to my side, a bull passes. I cringe and lock my legs. I could reach out—and it could reach in—

But it doesn’t.

The bulls pass and people yell—people yell with a new sense of confidence and charge forward.

“Let’s go!” someone yells.

Someone steps on my heel and my shoe nearly comes off, but I am able to reach down and fix it in stride.

We run with new hope and I wonder if they know more will be coming. At first I was told there was one group of six, but yesterday I was told there would likely be three groups of several.

I move out of the pack and sprint for a few seconds, judging by the relative calm that I have a short period of time to cover ground before the next group comes, but I have no idea how long. I sprint—I fucking sprint like you can only sprint when you are sprinting from danger, I sprint with fucking urgency, and then move back to the right. I am in good position along a wall and am still moving. I feel safer than I have since I entered the road almost an hour ago, but the panic rushes right back in again when the volume climbs and I see three bulls over my left shoulder on the inside of the road.

Someone steps on my right heel. My shoe starts to come off. I grasp at it with my toes without diverting my attention and hobble forward in the crowd, keeping my weight right so no one can push me into the path of the bulls, my hands on the person in front of me. I hobble, shoe dangling, and watch the bulls pass—just don’t gore me, I can handle the rest—I reach down and try to fix the shoe with my right hand, balance with my left—just fucking do it! I do it without falling.

I don’t know if I will make it into the stadium at this pace. There is one more set of bulls behind us—I don’t know how many—and I have no idea how far I’ve gone. Some people are yelling like all the danger has passed, but I think there are more. People will try to close the stadium gate when the third group is through. I have to make a move.

I look over my inside shoulder and go.

I fucking go and see the long stretch of fence ahead of me on the right that tells me we are close. I fucking go GO GO. I can see it, I can see the stadium. I look over my shoulder and start turning left with the road. I’m on the outside, but I know I’m okay because the crowd is behind me. Then the volume rises and the middle of the road clears. I go right naturally, I think I’m okay. I’m past the turn and look over my left—it comes alone.

If you see one alone, escape.

I jump smack into the fence like Griffey and grab but don’t go over. I’m ready to climb in case it comes at me in this crowd—so sparse compared to before—

I’m not going over.

If you see one alone, escape.

I’m going into that fucking stadium.

If you see you alone, escape.

I don’t go over, I cringe, and it goes by.

It passes me and runs toward the stadium door and I don’t know if I should follow it but I do, I fucking sprint, I’m making it into that stadium, that stadium is fucking mine, I pump my arms and my legs, I pass people and pass people, I am making it into that stadium—that fucking stadium is mine. I see one of the huge red doors start to close and I sprint toward it. The gap of light inside is closing, but the closer I get, the higher up in the stands I can see oh my god a sea of white noise. I see people on the sides as the bull passes through and is guided out the other end. There is a jam of people at the closing door and I run right up to them. I keep pushing forward and squeeze through the door and fucking sprint into the tunnel. I gain speed and the stadium reveals itself—full of screaming fans—everyone in white with their red neckerchiefs. I feel the dirt below my feet so soft and forgiving and I am displacing it all and I am in the Plaza de Toros, the motherfucking Plaza de Toros de Pamplona, I start yelling as I run—I fucking scream and let it out. I let it all out and it flows out of me like a release of pressure that shouldn’t build in a person. I scream and in the very middle of the circle—I’m in a fucking bullfighting ring—I’m in the Plaza de Toros de Pamplona on July 7 and people are screaming for me and I am letting it all out, it’s flowing from me, I stop in the middle and start jumping with the others. I jump and I scream and we chant and I jump, I fucking jump higher and higher and release it all. I know Dan is here with me, I can’t see him but I know it. I raise my hands above my head and jump so I am facing different directions—all these people—all these people in white standing, waiting for me to get here, all these people—twenty thousand, twenty-five thousand, a million—cheering me on.

I look up at them, they look down at me and we let it out and release it—and it all makes sense—

This is why—

This is who I am, maybe it will change, maybe it—

Maybe there is a moderate amount of self-preservation revealed through a self-destructive—shut the fuck up and jump!

I’m connected to people I don’t know. I jump I fucking jump. A part of a culture so foreign—immersion I’ve never known. Acceptance and capability—fucking whatever just jump! And I don’t feel proud, I don’t feel brave and I don’t feel manly or deserving or fortunate—just yell and jump and turn in the air and see the white, the cylindrical wall of white bodies enclosing me, centering me, thousands of white bodies building up and out above me in this stadium, this bullring—hear the volume and jump and yell and it flows back and forth, me to them and back again, and I feel—

I just feel—oh my oh my do I feel.

[[1]]: Research shows Dan is not a reputable source. People have died as recently as 2009.