The Mother Wave

Before the days of GPS, sailors navigated using the feel of the waves. On a mission to learn the ocean's secret rhythms, a researcher discovers a coded message in a ship logbook.

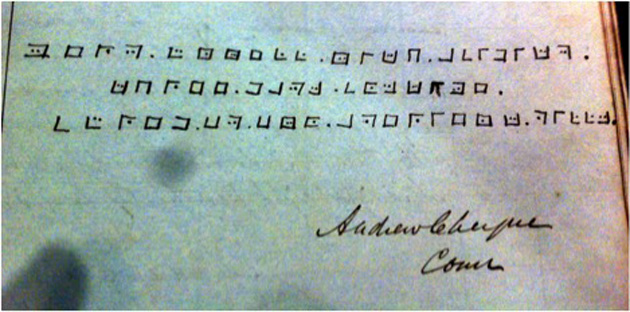

In the Shetland Museum and Archive’s study room I flip through the logbooks of a long-dead sailor, Andrew Cheyne. These are logbooks of various ships Cheyne rented from investors from about 1840 to 1860. Back then, the captaining of a commercial vessel was more like a life-or-death Kickstarter campaign than a romantic independent undertaking. He raised the money to sail and trade sea cucumber and sandalwood from often-shady ship-owners and generally ended up in debt. Each logbook is meticulously filled with a looping, slanting, barely comprehensible cursive script. In one of these logbooks I found a mysterious passage. It is the only place in the logbooks where Cheyne concealed his message with a code:

Cheyne wrote openly about taking hostages in Chuuk, about murders on Pohnpei, and betrayals in Hong Kong and Sydney. But on this page he decided he must obscure his message for the ages. This code had most likely gone undeciphered for over a century, and I, suddenly a scholar of the Nicolas Cage school, would be the one to crack it. Perhaps it would be the key to understanding the man, what this one life meant to the world.

When I cracked the code, I guess it did show me the man. Just not in the way that I imagined.

Thick, wet kelp lays on slick rocks like brown strips torn from an old book. Waves rake the pebbles on the beach with a strong burbling hiss. Beneath and above and all around that hiss is the constant roar of ocean and a vicious wind. On this beach at Stenness in the north of mainland Shetland, the remnants of an old fishing station still stand and provide shelter for the occasional wandering sheep or tourist. The station house, or böd (in Shetland dialect), is now a roofless stone shell covered in bright yellow moss on the ocean side. Gulls perch on greenish, weathered wooden beams inside. A sign informs me that up to 40 boats would launch into the far haaf, or deep sea, from here during the summer fishing season. Sometimes the boats would be away from the sight of land for three days.

Those who ventured into the haaf were called haaf-men. Before the satellite age they ventured miles into the haaf without the aid of celestial pings. The men spent days at sea on their sixareens, six-oared clinker-built boats, setting nets for cod. The sixareen is a Viking raider-style boat with a single sail, about 30 feet long, and requires a crew of six haaf-men, one at each oar. A day or two out, say, and the haaf-men might notice a disturbance on the surface of the ocean, a certain pile of clouds, or a strong wind, and know that they were in for a storm. The storm would disrupt the ocean, turn the boat around, blot out the sky. Once calm returned, a seasoned haaf-man could find home. The ocean told him which way to go.

Three days on a tiny boat, out of sight of land, amid a chaos of waves and wind, and with a heavy hull full of cod.

Did they just shit over the side?

I wonder if anyone ever drowned because they were shitting over the side of a sixareen and fell into the haaf (and if there were, perhaps, a folk song about such a thing). At the Shetland Museum and Archives, collections curator Jenny Murray queried everyone in the office and informed me that they reached the tentative conclusion that the sailors did, indeed, “poop over the side of the boat!!” (Exclamations hers.)

During the heyday of Stenness, as much as there ever was a heyday in Stenness, in the early 19th century, Andrew Cheyne (pronounced “Sheen,” but really lean into the “ee”) would have set sail in a sixareen, come back with cod for curing and drying, and helped the laird (lord) tally the take. Cheyne was the illegitimate son of the laird of Tangwick, a rocky beach and small conglomeration of crofts just down the coast from Stenness. Lest “laird of Tangwick” sound majestic to you, I have been to Tangwick and visited the laird’s house, preserved as a museum, and let’s just say that being “laird of Tangwick” is a nice-sounding title that would have given you a certain amount of respect among the rocks and sheep and few poor crofters on a treeless chunk of island facing the Atlantic Ocean, but little of note beyond that.

Cheyne comes across in his logbooks as one of the least introspective writers to have left what amounts to a diary spanning 20 years.

Cheyne was not particularly special. He would have faded from memory like any of the haaf-men in Stenness but for the trove of logbooks he left behind from his time as a ship’s captain in the Pacific. Some of these were collected and reprinted in the early 1970s by an Australian researcher. I encountered this book at the Micronesian Seminar, a research library, over a decade ago when I lived on the Micronesian island of Pohnpei. Cheyne lived on Pohnpei where I lived on Pohnpei. He failed spectacularly on Pohnpei where I failed ordinarily on Pohnpei. Cheyne comes across in his logbooks as a colossal prick (Indian “lascar” slaves, white-male superiority complex), a self-serving but naïve schemer (he seemed to trust everyone), and one of the least introspective writers to have left what amounts to a diary spanning 20 years.

I launched a scheme of my own after I saw a “call for papers” on my Twitter feed for the St. Magnus Conference in Lerwick, Shetland. I can travel only on the basis of conference proposals and institutional funding, so I wrote a paper about Andrew Cheyne that got me an invitation to Shetland. Three funding sources, two flights, an overnight ferry, and a rented car later I was standing on a cold rocky beach, trying to make sense of Andrew Cheyne and myself and anything else that drifted ashore at Stenness on a cloudy April day.

Cheyne launched several extensive trading voyages throughout the mid-19th century, encountering barely contacted island cultures along the way. He is not much remembered in the Pacific, as far as I know, but his Shetland genes live on in islands throughout Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia. I base that claim on the fact that a photocopied picture of one of his sons, from the island of Palau, fell out of a packet of letters I was reviewing in the Shetland archives. This son, who took the English name Otto, is a brawny man wearing a traditional thu’u. The thu’u is basically a colorful jock strap with a flap in the front. He is dressed, in other words, as unlike a Shetlander as one can be and yet, if you look at him closely you can see, in the shape of his nose and his eyes, a northern European mien.

None of this matters, of course.

What Andrew Cheyne did on Palau 150 years ago is not going to change the world, and yet when I see the photo of Otto, I think of Cheyne’s expanding progeny in Micronesia; of a wave of life, of combining and recombining DNA, traveling through time undetected. The code is there, just out of sight, visible only to those who know how to look, sometimes surfacing in the face or eyes of a newborn, an echo of a long-dead sailor. My Micronesian daughter was born with red hair and blue eyes, recessive traits; for all I know, Cheyne is her great-great grandfather.

I’m not sure what I am hoping to accomplish by standing on this spot in Stenness. To be a ripple in the story of a long-dead ocean trader? To say to a ghost that I, too, have lived on some faraway islands, have failed miserably, have fled home and comfort for no discernible reason and ended up on a far shore with no great plan but to just be there?

I’m not sure what I am hoping to accomplish by standing on this spot in Stenness.

Cheyne is still remembered here in the north of Shetland, by the few who care to remember him, as the man who was eaten by cannibals in Palau (he wasn’t) and the man who took his pregnant wife on a trading voyage from Shetland to the Pacific (he did), leaving her to give birth on the ship while it was in port in Tasmania. (His only mention of her I can find in the logbooks are these two words: “Elizabeth aboard.”) He never really knew his legitimate son, whom he left with his Shetland in-laws while he went to sea. His wife died young in Shetland. His son grew up to be an expert on gangrene and infections in World War I soldiers. Captain Cheyne, for his part, just sailed and schemed in the Pacific until he was murdered (but not eaten) on Palau.

It’s his failure at business and life that attracts me to him. He probably wasn’t a good man. He didn’t add much to humanity’s story, though he must have been pretty brave and pretty foolish, and his life ripples outward and makes tiny adjustments in the lives of others, for good or ill. Like George Eliot said of Dorthea at the end of Middlemarch, his “full nature spent itself in channels which had no great name on earth.” Words that are both comforting and frightening, the perfect words for Cheyne and me and most of us who spend our nature in obscure places, doing little-remarked-upon deeds. Wondering what effect they might have, if any, no matter how small, in the great unknowable ocean of the future.

The haaf-men in the sixareen might bale water for hours without sleeping before the storm passed and they got a chance to get their bearings. The open ocean speaks with sound and feel as much as sight. Today we can compute the algorithmic undulating of the waves, the mathematical chaos of crests and troughs, but cannot create the North Atlantic Ocean as it is: a chattering liquid code by which Shetlanders can find home. A true haaf-man felt the Moder Dy, the mother wave, and could point the sixareen towards Stenness even out of the sight of land.

The mother wave. When I first heard of it, it sounded like magic. A kind of knowledge that is not knowledge at all, just innate, ineffable knowing.

Captain Mau said that knew his direction even while he slept at night. Curled up in the hull of the boat, he could hear the message in the rhythm of the wave.

Once, cross-legged on a cement slab in a feast house on the island of Pohnpei in the Pacific Ocean, I asked a wise man named Mau Piailug how the waves spoke to him. Captain Mau, a Micronesian from a tiny atoll called Satawal, had sailed over 3,000 miles from Hawaii to Pohnpei with his team using only traditional navigation. Captain Mau was a generous man who spent years on Hawaii passing along the knowledge of navigating using the stars, whether or not certain birds or fish were present, and reading the ocean waves. How could he, out of that chaos, know what the ocean was saying? Captain Mau said he knew his direction even while he slept at night. Curled up in the hull of the boat, he could hear the message in the rhythm of the wave. I kept asking him what he meant and what exactly waves could say but Captain Mau had sized me up and, it seemed from his expression, decided that I wouldn’t make a good student. He smiled and said no more.

A decade later, during a session at the St. Magnus Conference in Shetland, I finally began to understand what Captain Mau was saying. Dr. Ian Napier of the University of Highlands and Islands in Scotland was presenting a conference paper on the Moder Dy. Sitting in the presentation, I wished I could say to Captain Mau, who passed away in 2010, that I finally understood what he meant when he said that he knew directions in his sleep, without even stars or birds or any other markers, and that I was a wiser person now, and that the steady beat of the waves at night when you are sleeping on a small boat is like our mother’s heartbeat: the most basic, essential, deeply felt, mysterious marker of the way home.

Dr. Napier, a very indulgent scientist, was kind enough to help me with basic facts about waves, specifically the Moder Dy. His conjecture is that the mother wave “is long wavelength waves reaching Shetland from distant sources in the Atlantic Ocean or Norwegian Sea.” A wave is born of wind and tide, and as it travels the ocean the wavelength gets longer and more regular, a directional drumbeat. A haaf-man might note the steady, long wavelengths tipping the boat and know that waves coming in this direction have an east-west orientation and therefore, among all the wind-whipped local waves, a haaf-man could feel the touch of the Moder Dy on the side of the boat, as good as a compass rose to a man who knows. The men could row the sixareen back to Stenness, salt and dry their cod on the beach, then head back out to the far haaf.

Lerwick is the largest town in Shetland. All of central Lerwick is shades of dark stone. If you turn your back on the oilmen in the garish flotels moored in the harbor and move upward to the dark stone streets and dark stone buildings piled one on top of the other, you can sense in each damp footstep a centuries-old maritime energy sleeping in the shadows. One night, my gut warmed by Orkney whisky, my head abuzz with excitement to be there, I stumbled around the old town.

There had been a lavish and boozy dinner. The dinner was the official opening of the conference and held in the gothicly appointed town hall where I was welcomed by the Mayor of Lerwick as some kind of actual visiting scholar, not just a guy with an active imagination who wanted to sit on the stones of Stenness. We sat in long tables beneath the mazy oak ceiling looking like a community theater production of Harry Potter. Later, bopping around the steep alleyways of Lerwick, I glommed on to a keynote speaker. He was an English scholar of Icelandic folklore, skinny of jean and expansive of mind. I followed him up a flight of stairs to The Lounge, where we occupied a corner of the small but friendly pub that seemed to be made up of nothing but corners.

Soon, The Lounge was populated with Shetlanders young and old. A musical trio materialized at one end of the pub. Accordion, fiddle, and drums filled the small space with a looping, spastic energy. Each turn of the reel topped the next, sometimes expanding the music, sometimes contracting, like waves on a frothy ocean. This is it, I thought. The real Shetland experience where the real reels are spun on real evenings with real locals. Then a group of women in drag entered.

The steady beat of the waves at night when you are sleeping on a small boat is like our mother’s heartbeat: the most basic, essential, deeply felt, mysterious marker of the way home.

They were dressed as metalheads, with classic Iron Maiden and Guns N’ Roses tees and stippled-on stubbly beards and unfortunate tattoos. One lady had dyed her hair blue. They cleared a space and started to dance. They did a skipping, elbow-in-elbow reel of the type I had not seen since I was forced to take square dancing for high school gym class. This group of women was joined some time later by another group of women dressed in ’20s flapper garb. One of them was a gorgeous bride in a sleek white dress and white net hat set askew on a bed of flowing red locks. The keynote folklorist and I were joined by three wandering Norwegians who had academic appointments regarding historical fisheries. We were having some kind of conversation about costume and tradition in Shetland that was interesting but difficult to follow in the din of fiddle-music and the Heavy Metal Flapper conflagration happening before our eyes. Then a metalhead with simulated stubble, safety glasses, and very loose jeans strapped on a felt penis. A thick old man at a table of old men, whose neck appeared to have traveled into his guts, bust out the most genuine, loud, and infectious belly laugh I had ever heard. His head turned beet red as he struggled for breath. There was a moment where it seemed entirely plausible that this man would expire right there and then because of the heavy-metal dick-lady. And then he let loose another barrage of guffaws.

That’s when the trio launched into “Mamma Mia.” The old men (still laughing) joined the costumed ladies to dance a reel among the tables. The entire pub, Norwegians, Shetlanders, Scots, ex-pat Icelandic folklorists and one American, all knew the lyrics, of course. So we sang and danced, and this obscure pub on a sparsely populated island where the North Sea and Atlantic Ocean meet was suddenly a post-modern jumble of sign and signifier, heavy metal flapper europop spun through ancient reels. Among the local waves was a deeper, steady, human rhythm. A code, a mystery, symbols of the past thrown together and set on a dizzying spin cycle. Threads of life, ripples of fate, waves of culture, my past—Mamma mia, here I go again. My, my, how could I resist you? I knew the words to the songs because my daughter, a daughter of the Pacific, from the island where Andrew Cheyne, a Shetland bastard, failed to make a fortune, was obsessed with Mamma Mia. She spent hours copying the lyrics to the songs from the subtitles on our television. She accomplished this oddly monkish task before she could even speak English fluently. And now here we were and here was ABBA resurfacing and suddenly the crowd was united. Did all this add up to something? This woozy, cool, felt-dicked night of Swedish schmaltz and Shetland reels? Within the whirring fiddled chaos, the familiar notes of ABBA act as our modern Moder Dy. A deep wave from across the Norwegian Sea.

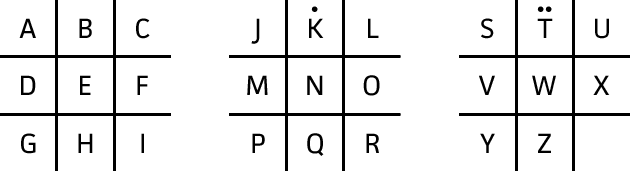

Back in my room, I searched for ciphers that look like tic-tac-toe, and in 0.44 seconds I had a link to a Wikipedia page regarding the “Pigpen” cipher, aka tic-tac-toe or Masonic cipher. Soon, I figured out Cheyne’s version:

The first mark of his code, with two dots and a “U” shape pointed 90 degrees to the left, is pretty clearly V. The next, a box with no dot, must be E. Soon I had the word “Very.” The next word is “unwell” and so naturally I thought this must be some kind of deathbed confession, the kind of thing that Cheyne would only reveal if he thought he was facing his demise. Perhaps he is confessing some sin? Or sending a coded message to his son, a boy then living with his grandfather on the tiny island of Fetlar. This boy would not know that Cheyne was his father until after Cheyne’s death. What might the father want to say to his son? Is this where I would find the real man after all, obscured by code?

“Very unwell with acidity. Three days cost. I’ve cured by two aperient pills.”

Translation: My constipation left me bedridden for three days, but I took some pills for it.

It’s difficult to describe the full suite of emotions I felt decoding this message. The thrill that it could be deciphered at all. The excitement of getting the first word. The bliss when the second and third words made sense. My racing heart when I looked up the word “aperient” and the sudden realization that this was a 150-year-old coded message about constipation. The crushing blow that this was not some important discovery. The deep, soul-shaking hilarity of it all that settled on me in my little room in a guesthouse in Lerwick. I shared this discovery with Jenny, the curator at the Shetland Museum. She could barely contain herself and finally exclaimed: “He dinna want the folk back at home to know he could na’ take a shaet!”

A long time ago on a two-masted brigantine in the Pacific Ocean, one Shetland captain, a native of Tangwick and Stenness in Northmavine, Shetland, had a bad case of constipation. But he took a laxative, perhaps a senna-infused spirit of Black Draught (don’t sail without it!), and he finally had his movement. This movement was so momentous and memorable that he had to record it, but in code, in his logbook. (Yes, I know.) It’s unclear who he meant to share this little fact with or why he was compelled to memorialize it. But now we know that Andrew Cheyne was constipated. He was, after all, just a man. And all he had to offer, all any of us have to offer, is our humanity.

This was my thought on my last day in Shetland when I drove back to Stenness just to be in the presence of the place, to sense the echo of this unimportant and horribly constipated man:

All that you have to offer the universe is humanity, however you choose to express it.

The thought arrived without snark or pretense or ego. I felt it once, there, and then never again with same weight or meaning: What does it mean? It’s too general. Too clichéd. Too uncomfortable because it comes unmitigated by any screen between myself and my experience. I feel as barren and exposed as the old roofless böd.

The thought is with me, almost always now. Written on the page it collapses into so many words and lies there like cod drying in the summer sun on Stenness beach. How can I speak of something that exists somewhere beyond language? Like the tug of currents or the sound of the beating heart of your mother as you curl unborn in the womb—it’s there, but elusive, indefinable. It’s humanity. It’s life: Full of sound and fury and poop and signifying … what?

All that you have to offer the universe is humanity, however you choose to express it.

It’s humanity. It’s life. It’s Mamma mia, now I really know, ABBA at midnight. Our full natures spent and sung in places that have no great name on earth. Our unhistoric acts, our hidden lives flowing, incalculably diffuse, into the future. It’s My, my, I could never let you go, whatever it means to make music, to encrypt your intestinal distress for future generations, and to know that in the most chaotic ocean, in the most cacophonous nightclub, on the most dismal voyage, there is a deep wave, an old song, a steady heartbeat that can guide you home.