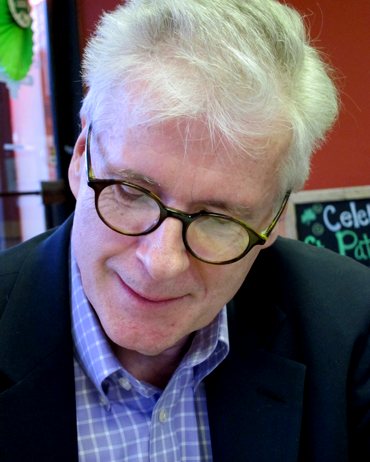

Thomas Mallon Redux

The rise and fall of Richard Nixon has been the subject of many histories, but perhaps none so insightful as Thomas Mallon's latest novel Watergate. A conversation about crime, ambition, booze, and Christopher Hitchens.

Given the deplorable state of historical literacy in the greatest country in the world, I have long held that if I were allowed to teach history there are a number of novels I would include in my lesson plans—in addition to the eye-opening, ground-breaking People’s History by Howard Zinn. Thomas Mallon has written a number of those novels—Henry and Clara, Two Moons, Dewey Defeats Truman, Bandbox, Fellow Travelers, and now Watergate.

This is the fifth or sixth conversation I have had with Mallon since the mid-’90s. Needless to say, he is a delightful and erudite conversationalist. Watergate, the historical event, which we both remember vividly, occupies much of what follows, including postmortems on Nixon, Kissinger, the Mitchells, John and Martha, and some others. Additionally, Mallon dedicated Watergate (the novel) to his good friend, the late Christopher Hitchens, which, of course, sparks an enlightening tangent on Hitch.

By the way, it should be useful to keep in mind that what follows is a chat about both a nexus of historical events and a novel of the same name.

Robert Birnbaum: I keep reading that it’s the 40th anniversary of Watergate. So what? Why should anyone care?

Thomas Mallon: The [book’s] publication was not timed for the anniversary. In fact the book was ready to come out in the fall. I would have been happier if it had—it would have been an easier semester for me, traveling around. And I don’t think Watergate anniversaries have been big, generally. The problem is there is no one thing to peg the anniversary to. You could do an anniversary for when Nixon resigned, the anniversary of the break-in—so I think it’s just a journalistic convenience to mention it.

RB: Did I miss John Dean’s review of your book?

TM: Just this morning I saw—I was sent something.

RB: He mentioned the book in the context of a review of Max Holland’s book about Mark Felt [Deep Throat].

TM: That’s right.

RB: Dean suggested he wasn’t going to read your novel.

TM: He said his friends were reading it. They were asking him, “Did Mrs. Nixon really have an affair?” And he said, “No, not to my knowledge.” And he didn’t think she could have had an affair in the way she does in the book. That I didn’t quite understand. The affair she has in the book predates the Presidency. It’s an affair she has in New York in the ’60s.

RB: Doesn’t she meet her lover in South America?

TM: In Brazil. He meets her there but they have two fleeting and chaste encounters in the context of these big public events. So I wasn’t quite sure what he [Dean] meant by that.

RB: This is historical fiction, which readers ought to be reminded of. But why create a love affair for the character, Pat Nixon?

TM: I think in some ways it’s the emotional heart of the book—Mrs. Nixon and this affair. Frank Gannon [in the Wall Street Journal], he was quite nice to the book but he did not like that.

RB: Many reviewers have lauded the book.

TM: People have been very kind—I’ve been delighted. But he was left queasy by the affair. He said, “Imagine the Nixon daughters reading this.”

RB: He quoted you saying you can’t libel the dead.

TM: It’s very interesting what he tried to do. But finally, I had to disagree with him. I had written in an essay that there are things you shouldn’t do to the dead even though they are dead and can’t be litigious. It was in reference to a movie that was made that implied that Thomas E. Dewey, who was once a character in one of my books [Dewey Defeats Truman], had actually been corrupt. To me, to say that Mrs. Nixon might have had this tender, brief affair is not an iniquitous thing. I fictionalized her life more than some of the others, but in a way this falsity or invention somehow allowed me to get inside her head in a way I don’t think I could have otherwise. In a peculiar way it got me to some aspects of the truth about her via invention.

RB: Again, the critical chorus was adulatory. One critic called the Watergate episode “vaudevillian.”

TM: It may be my own fault because I wrote the flap copy myself.

RB: That’s one part of the book I didn’t read.

TM: And I did write in the flap copy (picks up book), “It conveys the comedy and the high drama of the Nixon presidency.” And there definitely were comic moments in it. But I have been somewhat surprised by the reviews that have emphasized the comedic aspects of the book. More than I expected and even more than I thought they existed.

RB: There are a lot of characters, but Fred LaRue becomes central to the story. He has this personal tragedy and an odd relationship. Why focus on LaRue?

TM: He appealed to me for a couple of reasons. I remember seeing a documentary that was made about 20 years ago and was featured in it. His soft-spokenness, his shyness, the fact that he choked up at one point. He just began to intrigue me. There are about three invented characters in the book. The tip-off in the dramatis personae is the three names in quotation marks. And the woman he is involved with, Clarine Lander, is also a fiction. But the great calamity of his, prior to Watergate—he had killed his father in a hunting accident in Canada and inherited a lot of money. Naturally, a certain amount of suspicion or whatever you want to call it is going to cling to a person in those circumstances. That intrigued me. He is very shadowy.

I am not very good with villains generally. I think the closest I come to villainy in my books is the shadowy presence of John Wilkes Booth.

RB: Did he never find out if it was an accident?

TM: In my story he never really knows. And that gets all wrapped up with what happened in Watergate years later. He’s very shadowy. He had no title, no salary. He did a lot of things for John Mitchell, whom he really loved. And he lived in the Watergate. He intrigued me as a presence, and there was one newspaper profile of him in September of ’72, prior to Watergate really exploding. It suggested something like, “He seemed to be out of one of [Faulkner’s] Snopes novels.” And that appealed to me. I had a list at the beginning—I still have it in my files somewhere—with dozens and dozens of names that were potential point-of-view characters. And it finally came down to seven. There’s a huge cast, but only seven—

RB: And you cast Alice Longworth prominently. I lived through Watergate I don’t remember her presence. Was she interviewed a lot?

TM: A little bit. She turned 90 at the time. Nixon went to her birthday party at DuPont Circle. She wrote somewhere, when time was running out for him, “Oh I think the clock is dick, dick, dicking.” She had known him from the time he had come to town in the ’40s. She had marked him as a comer. She was very fond of him and Pat, and at least one of the daughters. She said to an interviewer, one time, “Yes, Julie. And Tricia, what’s wrong with her?” She was in the Nixon White House more than I thought when I began looking at these schedules. So I made her into my one-woman witches’ chorus. People have wondered why I didn’t make Martha Mitchell [that], who was so flamboyant—

RB: She was a drunk.

TM: (laughs) That’s the problem. She was really too far gone in a way, for most of Watergate. And she is really absent from the scene—the Mitchells decamped for New York pretty early on. She just wouldn’t have worked.

RB: From the outside, John Mitchell struck me as a gruff and unattractive person. He does come off as a more sympathetic character in your narrative—as do most of the people.

TM: I am not very good with villains generally. I think the closest I come to villainy in my books is the shadowy presence of John Wilkes Booth [in Henry and Clara] (laughs).

RB: Haldeman? You seemed to get Nixon dead on—a misanthrope in a flesh presser’s profession.

TM: Yeah. There are people who claim that he actually liked politics and liked campaigning. I find that kind of hard to believe. What would be the point of writing a novel about someone that was just a mustache-twirling villain? I just wanted to see this with a certain intimacy. You are right; Haldemnn seemed sort of nasty in the book. But even there you tend to see him through Rosemary Woods—he’s the man who displaced her in a way. But it’s generally that old Graham Greene term—the human factor—that interests me.

RB: George Will’s review—

TM: It was actually his syndicated column.

RB: I thought he got it exactly right—that you learn so much from novels by Gore Vidal, Max Byrd, and Robert Penn Warren [“bring… men alive in ways that only a literary imagination can”]. Here’s the thing, it seems that no one knew who ordered the break-in, but what does beg for emphasis is that the real crime was the cover-up. That’s what brought Nixon down. One wonders what might have happened if he had cut his losses? Was he incapable of admitting he was wrong or mistaken?

TM: A lot of it involves Mitchell. It’s true that nobody knows for sure, to this day, who told them to go into the Democratic National Committee at that point. There is that whole kind of grassy knoll theory of Watergate that posits something very different that I don’t buy into.

RB: What, Castro funding the Democrats?

TM: Yeah, and then there is the whole theory that John Dean was the evil mastermind. But it was fairly easily established—a couple of phone calls was all it would take to establish the fact that Gordon Liddy had presented this plan for massive surveillance and—this crazy—you know, the Gemstone plan—in John Mitchell’s office in the Justice Department early in 1972. If Nixon had said at the beginning all those people are now fired from the committee and got Mitchell to take the fall, whether Mitchell signed off on it or not—this is not a meeting that should have ever taken place in the offices of the justice department and it would have meant sacrificing Mitchell—

To me the real Rosetta Stone of Watergate is the spring of 1970. It’s when Nixon goes into Cambodia and Kent State follows. There were massive demonstrations in Washington and a ring of buses around the White House. He makes that crazy middle-of-the-night visit to the Lincoln Memorial. The super-charged atmosphere of that—I remember this as a very young man. It was so intense.

RB: Which he had to do anyway.

TM: Eventually. If he had done it at the beginning he might have survived. But he didn’t want to do it. Mitchell had so much to do with making him president.

RB: How was it that CREEP was being run out of a government office?

TM: They knew Mitchell was going to run the campaign but he was still attorney general. There is a very large sympathetic biography of Mitchell called The Strong Man by James Rosen, which is very interesting. It won’t convince everybody, but it’s a full-bodied picture of Mitchell. Nixon ultimately blamed Martha Mitchell [for his downfall]. One of the things that was clear to me—the Mitchells were a love match. It was a second marriage for both of them. And Mitchell, I think, really loved Martha. But Martha was tremendously out of control.

RB: Was she always a drunk?

TM: I think so but her problems were really severe. She really needed to be in a sanitarium at that point. Nixon used to say that it was because of Martha—John’s preoccupation with her troubles —that [Mitchell] wasn’t minding the store. That’s as far as he would go in blaming him. But he was not going to cut him loose in ’72.

RB: They ultimately divorced, right?

TM: Yes, and she ultimately became quite ill and died in ’76.

RB: The break-in wasn’t the only illegality in that nexus of events—the plumbers and the burglarizing of Ellsberg’s shrink’s office, Donald Segretti’s dirty tricks—

TM: He was pretty low-rent. But even Mitchell referred to the White House horrors—they knew they had these secrets that were really—

RB: And lots of undocumented cash.

TM: Right. Well, as he famously says to Dean on that tape, “We could get a million dollars. It’d be wrong but we could do it.” People often date the point at which Nixon goes off the deepend to Ellsberg’s publication of The Pentagon Papers. So Nixon, like many presidents, became obsessed with leaks. And he forms this squad, “the plumbers,” to deal with them. And to some extent, yes, that is the crucial turning point. That’s what brings Howard Hunt into the White House. To me the real Rosetta Stone of Watergate is a year before that—to me it’s the spring of 1970. It’s when Nixon goes into Cambodia and Kent State follows. There were massive demonstrations in Washington and a ring of buses around the White House. He makes that crazy middle-of-the-night visit to the Lincoln Memorial. The super-charged atmosphere of that—I remember this as a very young man. It was so intense—that was what made Nixon have a Manichean view of the world, this us-against-them view. In some ways, that set in motion everything that followed.

RB: There’s not a lot of Kissinger’s presence, but it does say a lot about him (laughs).

TM: Well. It’s there on the tape. “Guttural rumbling gravities” or something. I wish I could quote myself better. Any time these tapes are released, anyone who has the slightest regard for Richard Nixon has to crawl into a hole for days. You hear these awful things, these slurs and all his prejudices. Many of which to Nixon were a species of tough-guy locker room talk—he worshipped toughness. This last batch, oh my god. Kissinger comes off worse than Nixon. They are talking about the plight of Soviet Jewry. And Kissinger says something like, “If a million Jews were to perish, it is not a national security issue. It is perhaps a human tragedy.” My friend Hitchens said, when those were released, “You got to love that perhaps.”

RB: You dedicated this book to Christopher Hitchens.

TM: Yes, I loved him to pieces. And admired him.

RB: I think many people did, even through the twists and turns of his politics. He was brilliant.

TM: Yes, very brave. Lived between two fires.

RB: What other journalist had himself water-boarded to ascertain whether it was torture?

TM: He was a very gentle person too. The tributes to him have been enormous and well deserved but that was the one side that they didn’t quite catch. In my novel Fellow Travelers there is a left-wing journalist for The Nation called Kenneth Woodford who is very kind to the hapless little gay guy protagonist Loughlin. And that was Hitchens, and he never recognized himself in it. I know he read the book—we talked about it. He even wrote something about it.

RB: Is there anyone that is like him?

TM: No, there is nobody. I remember he was debating a rabbi when the atheism book came out. And the rabbi said, “Now, Mr. Hitchens, I didn’t interrupt you.” And Hitchens said very softly, “You’re not quick enough.” (both laugh) I don’t think there was anybody who was as fast on his feet—he could debate anybody. And he was a literary man as well as a political man. I just think he was—I mean the grace with which he handled the last 18 months. He put up a brutal fight against cancer. The pieces he wrote for Vanity Fair about his cancer received a lot of well-deserved acclaim—a lot of people who read those pieces, what they didn’t realize was that all the time he was writing them he was still writing his pieces for Slate about Gadhafi, the election, and whatever was going on. Still doing his real work. He was becoming a memoirist. That was really quite heroic. They are reissuing three of his books in the next couple of months—the book about the Clintons, Kissinger, and the book about Mother Teresa. They have new introductions; I did one for the Mother Teresa book. Which means another few years in Purgatory, I’m sure. He had this very eclectic mix of people around him because he was on so many political sides. You could go to dinner there and Grover Norquist would be across the table, [Salman] Rushdie would be next to you. And he had a lot of younger conservative journalists during the Iraq War around—even political operatives, people in the administration—they were thrilled to have this blue-chip intellectual backing Bush’s Iraq position, and always used to sit there waiting for what I called the Mother Teresa moment. I would think, Just wait, the conversation is going to take another turn. They are going to have to deal with the fact that Hitchens is an unreconstructed socialist—he called himself a socialist until the day he died. And were going to have to realize that he was all of a piece.

I don’t intend to go on forever. People do. But not everyone has these bursts like [Philip] Roth in their 70s.

RB: So, did you have fun writing Watergate?

TM: I did. Much more than many other books (chuckles). One of the things I was amazed at was once I really dug into it, it came back to me so quickly. Details, quotes, minor players.

RB: Meaning you didn’t have to do much research?

TM: I did but it was all sort of there. Like dragging a file out from some folder. It stuck with me because A) it was so vivid and B) I was so young—you absorb and retain at that age. The amount of stuff available—[the players in the Watergate drama] all wrote memoirs, if only to pay their legal bills. There are all the committee transcripts, there are the tapes. It’s that rare subject where I wish there was less.

RB: E.L. Doctorow says he does as little research as he can get away with.

TM: I do think that anybody writing this kind of fiction, you have to start writing before you complete your research or else you fall into dissertation syndrome—“I can’t start writing until I have read everything.” And that’s a prescription for never ending.

RB: You had an opportunity to lionize Senator Sam Ervin but you ended up giving attention to Mississippi Senator Eastland.

TM: Well, Ervin is so familiar. Eastland was crucial to developing [Fred] LaRue. LaRue was the one who would bring to Eastland who was head of the Judiciary Committee, Nixon’s conservative judicial nominations, and he was another Mississippian. So I had a few Jubilation T Cornpone scenes.

RB: In writing a book like this is there a beginning and an end? What’s next?

TM: I’m going to write about Reagan next.

RB: What happened to the murder book?

TM: It’s been bumped again. If I ever do that one it maybe my tenth novel and that might be it. I don’t intend to go on forever. People do. But not everyone has these bursts like [Phillip] Roth in their 70s. I am going to try to write about Reagan’s Washington, set around the time of the Reykjavik summit, which was a thrilling, bizarre episode. I still write a lot of nonfiction and I am kind of grateful—I’m now 60, which is pretty young.

RB: It’s the new 40.

TM: It’s still young in absolute terms. I can see reaching a point—I hope I am a few books away from it—where it comes time to bring the plane in for a gentle landing. I still love writing essays and reviews and all the rest. Maybe I can content myself with that?

RB: Well, the conventional wisdom for maintaining mental acuity is “Use it or lose it.”

TM: I do think the real challenge in writing novels and particularly a book like this is organization and structure. There is this massive amount of material to corral into some sort of discernable shape.

RB: So many choices.

TM: That’s the thing. I had lists of dozens of characters—do I go with that person or that person? Eventually you have to make a decision and narrow it down and eliminate people. But I am generally pretty much done with it. I mean, you have that nice little magazine up here called Ploughshares and they are doing an essay issue that’s being edited by my friend Patricia Hampl, who is a wonderful memoirist. So she was putting the touch on all of her writer pals for essays. So I am doing a little nonfiction thing about Nixon, trying to figure out my preoccupation with him.

RB: Perhaps the greatest indictment of Nixon was in Charles Baxter’s essay “Burning Down the House,” where he faults Nixon for introducing the dysfunctional narrative by employing “mistakes were made…”

TM: The irony is we will never have a president who is more real to us than Nixon, for all his unreality, in that, yes, you have some tapes that Kennedy made, Johnson made, whatever. But to have those tapes—unbound, unglued—to hold against all of the recorded public utterances he made is an extraordinary experience.

RB: He taped everything.

TM: And he didn’t do it for two years. He got rid of Johnson’s taping system at the beginning. And then they decided that the quality of memorandum they were getting from people who were supposed to record meetings (the low man on the totem pole would be the note taker)—Haldeman, in his efficient system, so disliked the quality of what they were getting said, “Let’s just tape everything. These things aren’t worth a damn when you try to refer to them.” Once he did it, he went into it in such an enormous way. There must be at least one tape of Nixon listening to the tapes too,

RB: (laughs)

TM: Before the tapes were made public, and the system is then instantly dismantled, in the Spring of ’73, he wants to listen to a tape, particularly of that March 21 meeting with John Dean (“we could get a million dollars”). He has one of his aides rig up the tapes so he can listen in the executive office building hideaway—that had a taping system, too. So there has to be a tape of Nixon listening to himself. So the tapes do put you there in a way that they will never put you in there again.

RB: Do Americans want their president to be human, to be real? Mitt Romney is ridiculed for trying to be a man of the people

TM: Yeah, well, this crew that’s out there now—what he [Nixon] would make of them. The idea that an election would be hingeing on these “social” issues would just bore him. He even said to Mitchell at one point—supposedly said, just when the presidency was beginning—“You be president and I’ll be Secretary of State.” To him it was essentially the office from which the foreign affairs of the country were conducted. One of the reasons his domestic programs by and large were so liberal—guaranteed national income, health care, big funding for the arts, all the rest—I don’t think it engaged him very much. He wanted to be free of all that. Ehrlichman, who was in charge of domestic affairs, felt it didn’t get enough of Nixon’s attention. Nixon says at one point, taking to Rosemary Woods, and I use this line, “The country can basically run itself domestically.” A sort of Coolidge notion, in a way. Even though he went in for lots of government intervention and programs.

RB: Later there were efforts to rehabilitate him based on his foreign policy expertise.

TM: He wrote serious books and he never took a fee for a speech.

RB: Was he broke when he resigned?

TM: Yes. He needed to write his memoirs to make money. But they lived modestly at the end. He still did a lot of foreign travel and he gave his advice freely to every American president that followed him. Nixon’s epilogue scene here is his last trip to Russia just before he dies. And he reports on that to Clinton. And Clinton even says to his advisors, “Why don’t I get memos this good from my ambassadors and staff?” He was a much better ex-president than president.

RB: Clinton was particularly laudatory when Nixon died.

TM: He said something like, “The time has long passed when we should judge Richard Nixon on anything but the totality of his life.” In other words there was more to him than Watergate. I used to wonder how Robert Caro, year after year, book after book, stuck with Johnson (laughs). I still wonder.

RB: Malone wrote six volumes on Jefferson.

TM: I could sort of see this after just a couple of years with Nixon—I didn’t feel like I exhausted anything.

RB: I don’t know who wants to read those door- stop biographies. I like the 200-page biographical essays by someone who is simpatico—Larry McMurtry on Crazy Horse, or Cabrera Infante on José Martí. But I see that biographers like Caro are good about clarifying the social/historical milieu surrounding their subjects.

TM: Yes, yes. His books are these big history paintings, these murals. But biography—I’m not tempted. It’s too onerous, too difficult to go—It’s one thing to go from fiction to criticism, reviewing. But to go fiction to narrative non-fiction… I’ve been amused by this John D’Agata book, The Lifespan of a Fact. Not my idea of nonfiction. I worked on that little book of mine, Mrs. Paine’s Garage, after a real spate of fiction—Dewey Defeats Truman, Two Moons. I just found it so difficult not to be able to fall back on “Well, it’s a novel, I can change this.” It had to go through the strainer of the New Yorker fact-checking department. And I just can’t imagine that burden in writing biography, let alone just the burden of assembling all the material. I just can’t see it.

Aside all the campaigning he did for people, [Nixon] was preparing himself for the presidency. [Palin] couldn’t care less. With her it’s become president or get a better deal with a reality TV show.

RB: Have you seen Game Change?

TM: No, no.

RB: Do you read those kinds of books? Read the book?

TM: Not many. I read him, John Heilemann—I read him in New York magazine and I hope I will see the movie with Julianne Moore.

RB: She’s incredibly convincing as Palin. But everybody involved as player claims it’s fiction. The end the movie has McCain telling Palin she is now a kingmaker in the Republican Party. Is she a leader of the GOP?

TM: No, no. No. No. Look, I argued in 2008 with my friends that nobody who was in the United States Senate for three years was ready to be president. Nobody who was the Governor of Alaska for two years is ready to be president.

RB: John McCain was prepared to be president?

TM: Well, 14 years in Congress.

RB: George Bush was ready to be president?

TM: Six years as governor of Texas—that’s a weak office. Probably not, ideally. I think Palin had been to Mexico. That was her international travel. She stopped in Germany on her way to a lightning visit to Iraq. She had never seen any of the countries we’re allied with. That strikes me as incredible.

RB: But that’s what politics has degenerated to since Nixon—commercials and advertising. Eagles and flags and all the rest of the beer commercial imagery.

TM: Look in those years Nixon was out of office. As a former vice-president—anybody was going to see him. He was an enormous foreign traveler. He would meet with whomever was in power and the leader of the opposition too. Aside all the campaigning he did for people, he was preparing himself for the presidency. [Palin] couldn’t care less. With her it’s become president or get a better deal with a reality TV show.

RB: Quitting the governorship was a telling move.

TM: Also, how hard could it have been (laughs)?

RB: Who do you think could be president? Who could do the job?

TM: Umm. Well, uh, I was alone in my peer group who thought McCain could.

RB: Not based on his values but because he knows how things work?

TM: His experience, yeah. Even though he has been wrong on just about everything through the years. In terms of experience, Biden would be creditable. John Kerry was a creditable candidate. There are other reasons why I might not want them, but I do think people should know something. One result of 2008, and it’s a combination of Obama and Palin—in most respects there is no comparison (intelligence, curiosity, etc.)—but having both of them on the ticket, it has definitely driven down the expectation of experience. People with such thin résumés running for the top offices.

RB: That strikes me as basis for Biden’s place on the ticket.

TM: Oh sure. Once McCain put Palin on the ticket he lost the opportunity to say to Obama, “You’re not prepared to be president. You need more seasoning in the Senate.” Their obvious rebuttal would be the choice he made to be a heartbeat away. They threw away a pretty compelling argument. I think a lot of people would have looked at Obama and said, Here’s a very bright guy, come back in four years.

RB: Well, come back in four years with your Ronald Reagan book. Thanks again.

TM: I will.