What I Didn’t Write About When I Wrote About Quitting Facebook

The emergence of the Social Media Exile essay has been swift and smug. A language expert dissects a genre while also being seduced by its allure.

The first thing I didn’t write about quitting Facebook was a status update to my friends saying, I’m quitting Facebook.

I also did not write a proposal for the nonfiction book I imagined, which was about quitting Facebook. In the book, I would indulge the conceit that my Facebook friends are, actually, my good friends, and that the social network comprises a sort of community when taken as a whole. Then, as one does with one’s friends, I would call each person up or visit them and tell them I was leaving Facebook, which would create an opportunity to talk about Facebook and this whole social media thing, but mainly it would be to get to know something about who they actually were and why we were linked in the first place and what it all might have meant.

Eighteen weeks of five interviews a day would get me through my friend list, I calculated. Friends from high school and college and grad school. Friends of friends. Editors. Siblings and a couple of cousins, my in-laws. Random admirers and hangers-on. The resulting book would reflect our conversations about how much Facebook had enhanced our friendships and our lives in general, or maybe it hadn’t, and we’d talk about that, too. And we’d exchange info, and say goodbye, and then linger, and wave, and wave, until we couldn’t see each other any more—one of those departures where you look away out of exhaustion with the moment, then when you look up find they’ve gone, vanished, as if they hadn’t been there at all.

At the end of the book, I would actually unplug from Facebook, and I would write about that, too, and the heartwarming account of the ties that bind us would inspire you to hold your Facebook friends close, so close, because the time we pass in this mortal coil is so fleeting; we are truly encountering only the passing of the person, not the person in themselves.

I did tweet the observation that Facebook isn’t going to pay you a pension or 401k for all the time you spent there. Quite a lot of people liked this. So that was one veiled thing I wrote about why I quit Facebook.

But I didn’t write this, nor did I write a status update about leaving. When I quit, there were no goodbyes. No interviews. Just, I’m outta here.

Another thing I did not write about quitting Facebook was that one of the great social pleasures in my life has been to leave gatherings or parties unannounced. You know, when the party is socked in solid from the front door to the kitchen, and the conversation is drying up like old squeezed limes, it’s easiest to keep heading out the back. How cool the night. How open and unquestioning the darkness. “French leave,” we English speakers say. (“English leave,” the French say.) Often I went to parties to be able to vanish from them. But the disappearing act rarely happens any more; I could never get away with it. Such pleasures one has to give up because they’re so unsuited to middle-aged life. You get trained, after a while, to going to every person in the room. Hey, great to see you again. See you later. Send me a note about that thing. Yes, let’s do that. Goodbye, bye. The book idea was, in a way, testing out the durability of that social grace. But I didn’t write about either topic.

I did, however, start an essay that could have been about why I quit Facebook, except that I got distracted by the emergence of a genre you could call the Social Media Exile essay, and I wondered whether I could meet the conventions of that genre if I ever tried to write about why I quit Facebook, though the truth is, I didn’t really want to write another version of the Social Media Exile Essay, dramatizing the initial promise of this or that social media or network, the enthusiastic glow of online togetherness, then the disillusionment, the final straw, the wistful looking back. I did write that it seems like so many people have had their crack at “The Day I Quit Blogging” or “Why I Tweet No More,” which aren’t real essay titles but could have been, also like “How Google Broke My Heart” or “Farewell MySpace” or “Je Ne Regrette Rien, Friendster.” So this essay never got written.

I was also writing emails to former Facebook friends who had noticed that I was gone from their friend list and who were taking my disappearance personally, all because of what I hadn’t written about quitting Facebook—which I didn’t start writing, because I had to placate my friends. Really, it wasn’t because of you, it was because of the whole enterprise, I wrote, which had begun to throw salt on my misanthropy. I went no farther than that—I feared offending them if I wrote about how difficult it became to have peaceable face-to-face relationships with people who projected unlikeability online.

I was now talking a lot about quitting Facebook, and this for a time became the most interesting thing about me.

I did tweet the observation that Facebook isn’t going to pay you a pension or 401k for all the time you spent there, and quite a lot of people liked this. So that was one veiled thing I wrote about why I quit Facebook.

I didn’t write about the shock of finding out that the two dear sons of one of my Facebook “friends” had been tragically killed in an auto accident, not recently but two years ago. Somehow I had missed this fact, until an anniversary post by one of the grieving parents—the status update elliptical, scourged by grief—pointed me toward the incident. I do not know what I would have done or written if I had known before. I did not write anything to them now because I felt so ashamed of my ignorance amidst a wealth of things to click on and know about. A wealth of things that may not matter so much. It’s always been a world in which you can lose your children or your parents in an instant, but somehow I have made it this far without knowing that in my gut.

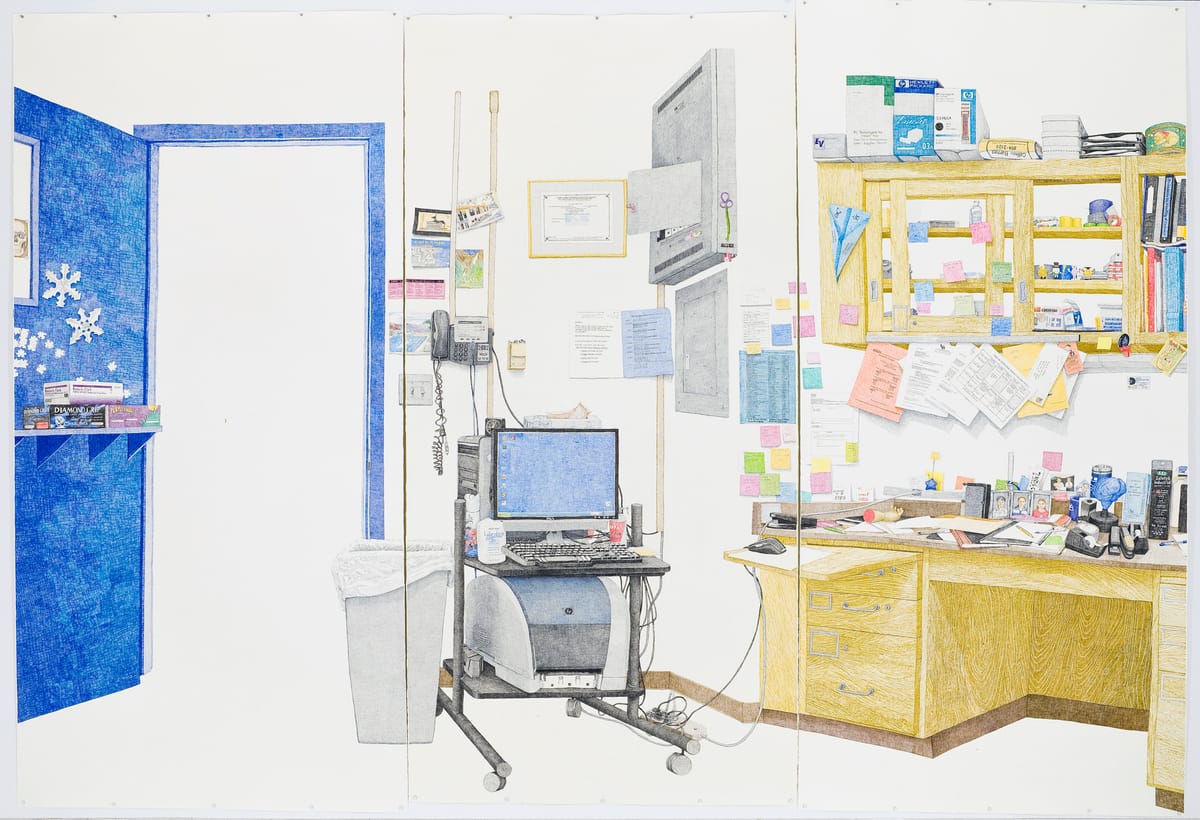

Instead of writing about any of this, once I was not on Facebook anymore, I found myself sending emails with some witty insights or photos of my baby, but it just wasn’t the same; a request for housing help for a friend via email got no responses. However, I was now talking a lot about quitting Facebook, and this for a time became the most interesting thing about me. Fueled by how interesting I now was, I wrote a draft of an essay about writing about why I quit Facebook, which was clever but did not contain any of the things I have already said I didn’t write about. Plus, as the editor pointed out, I didn’t actually explain why I had quit. I hadn’t written about feeling like Facebook was a job. Like I was running on a digital hamster wheel. But a wheel that someone else has rigged up. And a wheel that’s actually a turbine that’s generating electricity for somebody else. That’s how I felt, which is what I should have written.

I thought about how I didn’t want to write about why I quit, only about how great it feels to be free, because how often do you get to leave a job? Something along the lines of, you stand up at your desk, you un-pin the photo of your dog or loved one from the cubicle wall, and you walk right out the door, don’t take the elevator because it’s slower than the stairs, and you bid the thrumming hive adios. Leaving Facebook felt like that. The sun singing on your face like springtime. The birds all whistling your theme song.

In the standard Social Media Exile essay, one doesn’t mention or announce when one returns to blogging or Twitter. For each platform or network one leaves, there’s another one to return to. Sometimes they’re the same. So I’m going to close this piece by breaking that convention and mentioning how easy it turns out to be to reactivate Facebook. When you sign back in, all your stuff is there, as if you’d never left. It’s like coming back to your country after a month in a foreign land, and it makes one feel that the whole reason for leaving is to make the place seem strange again. Being away from Facebook was certainly that. But I had to come back. That’s where all the people are. I’ve got a book coming out, and I need to let my friends know. Anyway, you know where to find me and what to talk about when you do. I’ll have some cookies baked.