Where Death Lies

Each year, the Japanese government expects dozens of people to die from eating ill-prepared blowfish, and yet the dish remains a delicacy.

The tetrodotoxin level of the common blowfish is up to 1,200 times more deadly than cyanide. The toxin contained in an average specimen is potent enough to kill 30 adults. If prepared incorrectly, ingesting blowfish first manifests as a pleasant tingling on your lips before paralyzing you, and swiftly sending your body on a grand tour of bodily horrors—seizure, diarrhea, vomiting, convulsions. You die when your heart stops or when your throat swells in on itself.

The Japanese have eaten blowfish for centuries. Puffer bones have been found in the heaps of refuse accumulated by prehistoric hunter-gatherers who lived on the islands. The poet Basho even wrote a haiku about the delicacy:

well—nothing’s happened

and yesterday’s come and gone!

blowfish soup

In 1975 a famous Kabuki actor ate four servings of blowfish liver, claiming to be immune to the poison. He died shortly after. The emperor of the country is, to this day, forbidden to eat fugu, as the fish is called in Japanese. Chefs undergo rigorous training to receive fugu accreditation and yet, the Japanese government projects that 30 to 50 people will be poisoned each year due to ill-prepared blowfish, and several have died in the past decade. Just last year, five adult men were hospitalized after asking to eat liver.

When a plate of blowfish arrived at my table at Toro-Fugu Tei in Shinjuku, one of Tokyo’s 23 city wards, last November, the meat—pale pink and threaded with thin translucent bones—was still pulsing though the animal was skinned and expertly dismembered. I am an adventurous eater and like Basho I was curious about a fish that, a little larger than the size of my hand, could kill me in a matter of minutes. But until the moment the plate arrived at my table, I hadn’t truly considered the danger of eating this meal—the chance, however slight, that I might not return afterwards. So here I was, contemplating the shudders of rigor mortis, the fluorescent restaurant light shaking off the meat rhythmically, until gradually the pulsing slowed, then stopped completely.

The last Asian country I’d been to was Taiwan, two years earlier, on a family vacation. I’d fallen in love with Taipei, its raucous night markets and laid-back tropical atmosphere. My family is Chinese-American so getting around Taipei was no trouble—my mother and father are native Mandarin speakers, and I can get by in the language, too. I tend to recede into the background, however, when we’re together in any predominately Asian locale, even if it is, say, a Chinese take-out restaurant. Ma, can I have a Diet Coke? I’ll whisper to her in Chinese, only to have her turn immediately to the server to ask the same question on my behalf. I dislike having to drum up an explanation as to why I speak so slowly, why I’m the only one who drinks ice water with my meal, why I look Chinese but am somehow not Chinese at all.

My blissful week of non-interaction was interrupted only when I crept into a cab alone to go home from vacation. The sky was still black, the streetlights cast long yellow shapes on the asphalt as we drove. I preemptively apologized for my shitty Mandarin as the driver and I chatted in simple terms about the weather and what I did in New York. But when I told him that my parents were Shanghainese, he became animated, looking over his shoulder at me and smiling. “A famous Shanghainese woman once lived here. Do you know who she is?” I did. Soong Mei-ling, the wife of Chiang Kai-shek. He praised me for knowing this piece of trivia, and I felt a surge of pride turn quickly into shame, because her name, in the end, was all I knew.

Two years later, I arrived in Japan for a trip with a few close friends from New York. A few hours after landing, I sat in a smoky izakaya, my head burning from jetlag. The rest of my group, all of whom were white and relaxed from pints of Asahi, elected me to order for the table. A Japanese waitress stood by, smiling, her pen poised over her notepad. It was obvious I was a foreigner from the way I was dressed and from my company; but still, I felt some wild instinct flare up inside of me, an urge to acknowledge our shared ethnicity, to explain the distance between me and my friends, between me and her.

The first two dishes of the set blowfish meal were cold courses. Thin petals of sashimi arranged like a mandala on a plate. A fluffy salad made with thin ribbons of the skin, cilantro, ginger, and soy sauce. I drank a beer while I considered the translucent pieces of fish and watched the other patrons around me—we all sat in individual booths built from beams of blonde wood. One man who was waiting on his date noticed my gaze as he speared a piece of raw fugu. He winked as he popped it into his mouth.

I raised a piece up, too, examining the gauziness of the meat draped over my chopsticks. I placed it in my mouth—there was next to no flavor though the texture was delicate, like a fine sweet film. And while the skin had great bounce, it was basically flavorless, too. I told myself that whatever toxin lied within either dish was certainly too insubstantial to kill me.

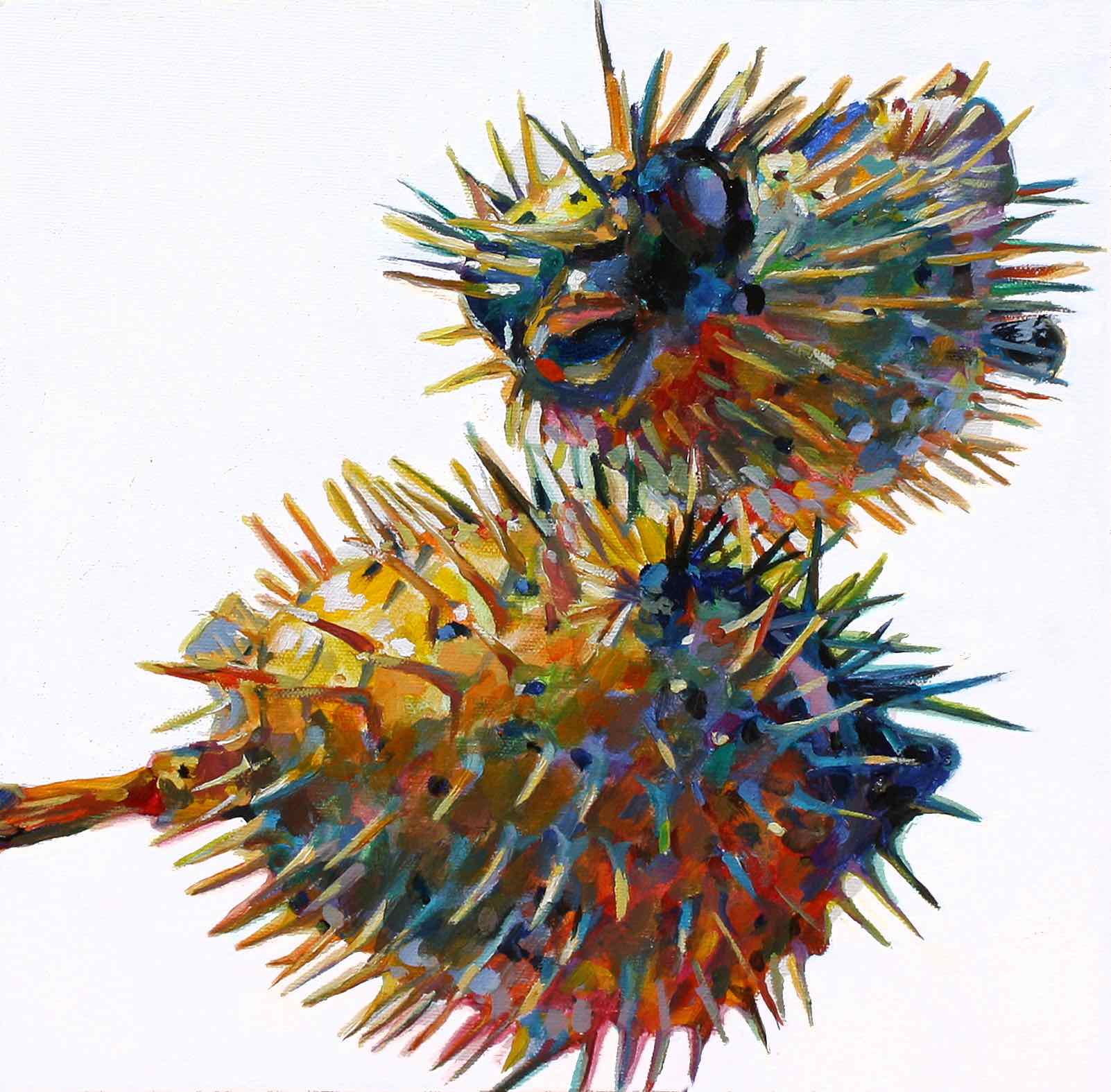

While I waited for the next course, I wandered to the front of the restaurant, where dozens of live blowfish swam in tanks. Their skin looked closer to stone than flesh, watercolor gray with large black spots just behind their collars. The belly of a blowfish is pure white and its tiny fins whirl like desk-fans, though these are only able to propel its body to stay afloat and bob slowly in the water. Aside from their toxicity, fugu is of course known for its ability to expand like a balloon to two or three times its size. To accomplish this feat, a fish will gulp water or air, expanding its stomach to a hundred times its natural size. The body becomes a tough sphere covered in tiny spines.

It’s odd to see such a remarkable creature amongst so many of its own kind—what might happen if they were startled? But of course, animals aren’t instinctively inclined to be frightened of their own kind. I traced my finger along one fish’s path, over its fluttering dorsal fin, its large amber eye.

In college, a Chinese professor asked me what I thought the culture of China was. When I faltered, she mocked holding a bowl in one hand and a pair of chopsticks in the other.

In college, a Chinese professor asked me what I thought the culture of China was. When I faltered, she mocked holding a bowl in one hand and a pair of chopsticks in the other. She mouthed the word chi—eat—as she scooped the invisible chopsticks toward her, as if she was bringing the word itself into her mouth. The lesson is reductive, sure, but it struck a chord with me because my family has always been enthusiastically gluttonous.

Sometimes, as my mother or father urges me to eat as much as possible at an unlimited buffet or salad bar, I think it might be because America’s excessive delights still seem fleeting to people who came to this country with nearly nothing. And though that is certainly part of it, I think the simpler truth might just be that we are all disposed to be interested in food—its history, its preparation, the worlds that can be discovered within a single dish. And I am fascinated by food, as well. But when I began to visit the homes of my childhood friends—mostly white Southerners in Tennessee—I came to realize that other families were not like mine. Many families ate precise meals off of coordinated tableware and did not endlessly debate the correct ways to soy-braise a shoulder of pork. And so I came to relate the act of eating with being Asian and day-by-day engaged in a bit of magical thinking: if I could just somehow suppress my interest in food, I could also hide that the part of myself that was Chinese.

At the same time, in the locker rooms of my middle school, I grew envious of my classmate’s nascent breasts and hips, their long narrow waists and sturdy architecture. I thought someday I too might wake up with an hourglass figure, but as I grew older my body only disagreed more. I looked less and less like the white girls on my swim team. I seemed to grow only wider and stubbier with age. So I ate smaller and more regulated portions, going so far as to reject my mother’s cooking in place of piles of salad with only a glance of dressing. If I could not control my shape, at least I could restrain it from filling in.

I have watched a troubling statistic grow in recent years, that young Asian-American women contemplate suicide at a rate far surpassing that of similarly-aged whites—at least one in six Asian-American women has considered taking her own life. One might theorize as to what is driving this spike—the fracturing of identity, a lack of cultural representation, the stereotype of overbearing Asian parents—but I can think of nothing as clear as standing in front of a mirror, worrying over shallow dips of skin and waiting each day as hope for a new kind of body seeps into one’s bones.

In Japan I felt my old tendencies creep back in. Though I was on vacation and walking immense amounts each day, I still felt guilt over eating exactly what I wanted. The nights I went to bed sober I would lay in bed willing myself to stop tallying up the courses, the drinks, a rice cracker swiped from a foil bag left open on the counter of the kitchen.

One night, we went to a hip restaurant in Roppongi, another district of Tokyo. Though it was winter, we sat outside on the rooftop, shivering under a heat lamp that kept turning off. The sushi at this particular izakaya was known for its flashiness, and we ordered a small mountain range of rice and tuna capped with bright orange uni and salmon roe. In a cloud of sake and excitement over the extravagant order, I lost count of what I had eaten. When I realized this, I immediately set my chopsticks down and forced my attention instead on the red lanterns strung on either side of us and the skyline of Tokyo shimmering around us.

“You’re the kind of person who stops eating after she’s full, aren’t you?” my friend Liz asked, touching my arm. I thought about continuing to eat and instead, invented an excuse. “I just want to leave room in case we order more,” I said. I recalled returning home once, when I was a sophomore in college, and walking in on my mother observing herself in the mirror while a black fabric belt vibrated around her belly. I asked her what she was doing and she told me she’d bought the belt from a television commercial. There was a thirty-day guarantee that the device would shave three inches from your waist.

“Don’t worry.” she told me, her smile sheepish, “if it doesn’t work I can return it.”

Years ago, when I’d just moved to New York, the only regular contact I had with a group of Asians were the women a white male friend exclusively dated. He’d gone so far as to filter his OkCupid account by race. Once, while we were at brunch, I asked him if he automatically right-swiped women on Tinder, so long as they looked Asian. He began to say yes, and then paused.

“I left-swipe any girl who lists “trying new foods’ as an interest,” he said “It’s all they want to do. It’s fucking boring.”

He’d been to plenty of dinner parties at my house. Enough to see that I, too, was interested in “trying new foods.” And yet, as I sat stabbing at a plate of overpriced and shitty scrambled eggs, I felt a strange satisfaction knowing he’d excluded me, at least for a moment, from the monolith of Asian-American women he fetishized.

I had only ever dated one race of person, too, though my trail of white exes was in part circumstantial; a majority of boys I had grown up around were white. But I wouldn’t be telling the whole truth to deny that I wasn’t instinctively drawn to them. In my relationships with white men, my identity as an Asian-American woman was discussed in only in innocuous ways—a bit of family history on a first date or a quick lesson on ordering at a Chinese restaurant, if things became serious.

Perhaps monolith is the right term, in fact. When you are treated as though you are part of a homogenous whole, it’s hard not to begin to believe in that monolith too. And if you can just set yourself apart from that vague mass, perhaps you can escape it. But escaping doesn’t mean that you wind up somewhere you belong.

The story my parents tell the most about my childhood has to do with another Chinese family who had arrived at our home one night for dinner. Their daughter was my age. When my parents instructed me to greet her, I did so tentatively, then fled up the stairs and into my bedroom.

In a shop in Shinjuku, nearly every piece of clothing I tried on fit my proportions. For the first time, a wool skirt sat snugly on my hips and fell at the right length, just kissing my knees.

“We’re ninety-nine percent the same, all of us,” my high-school English teacher was always fond of saying. He was a handsome white man who wore tweeds and played The Clash and Velvet Underground during class. From him, I learned to love literature and pop music. We are all ninety-nine percent the same—I repeated this to myself over the years whenever I was the only person of color in room or the countless times some white stranger has attempted to greet me by saying ni hao. But how could I still believe in the fundamental alikeness of all people when years later, in a department store in Tokyo, all the makeup matched my skin tone and all the faces in the posters resembled mine?

In a shop in Shinjuku called Studious, nearly every piece of clothing I tried on fit my proportions easily: an A-line dress, a leather jacket, a pair of elegant wedges embellished with pheasant feathers. For the first time, a wool skirt sat snugly on my hips and fell at the right length, just kissing my knees.

“The clothes here are made to fit you,” Liz remarked after we left. I confess I felt smug, to be the one who had an easy time in the fitting room for once.

My friends left Japan a week before I did; we said our goodbyes over quick bowls of udon at a train station in Tokyo. As I made my way through a sea of bodies to locate the Shinkansen, Japan’s high-speed railway, for the next part of my journey, something shifted. The expectation of what it meant to stand out in a crowd had left me. I was like a stone cast back into the sea.

My first night alone, I wandered along the river in Kyoto and I stopped by a convenience store to buy a beer and a riceball. When the clerk realized I did not speak Japanese, he instead switched to Chinese.

“You’re American,” he guessed, looking down at my sneakers. I smiled and nodded thinking of the red bandana and ripped white t-shirt I was wearing in the middle of November. I laughed, realizing how silly I looked. He smiled.

“Welcome!” he said, handing a small plastic bag to me.

Before my friends flew home, we’d driven together to the Noto Peninsula on the Northern coast of Honshu to steam away in an onsen in the middle of a sleepy fishing village.

Onsen were once the public bathing houses of Japan, though these days, many have been refashioned as relaxing getaways where weary travelers can enjoy dozen-course meals and deep tissue massages. The steaming water is pumped in from volcanic hot springs and patrons are expected to strip naked before sitting in the baths. The Japanese have long thought there to be value in “naked communion,” and the minerals in the water are also thought to have healing powers.

Ours was a window-lined room overlooking a tree-lined bay as the sun was setting. Steam swirled around the room, the pink afternoon light illuminating great billows of haze. I’d stripped quickly, before I could begin to consider any embarrassment over my naked body, and I tiptoed towards a row of showerheads, to wash myself off before entering the bath. A cool draft from the window drew goosebumps on my skin.

As I ran a hot stream of water through my hair to clean it, I heard quiet chatter coming from the far end of the bath. Through the cloud, I made out the bodies of four or five Japanese women and tried to observe them covertly. But even from the peripheries of my line of sight, I felt a recognition so deep it was as if my body itself had interpreted the familiarity of their shapes. It felt like weight slipping from my back or the clarity of early morning light. It felt like someone I love saying my name.

The server poured water and kombu into a bamboo basket that had been lined with a single sheet of white paper. She instructed me to turn on the burner underneath. When the water boiled, I dipped pale pink cuts of fugu into the broth, then dipped these into a light vinegar.

A debate over whether or not blowfish can be bred to be nonlethal resurfaces every few years. Farmers and scientists have repeatedly claimed to be able to jettison any toxicity by controlling the animal’s diet, but the Japanese government refuses, still, to acknowledge the science. Most recently, this month, the Japanese government again dragged its feet on lifting the ban against eating all parts of farm-raised fugu, fretting that consumers might believe all blowfish safe to eat. If it’s true that farmers are able to breed nontoxic blowfish, one has to wonder whether there will be any market left for fugu, at all.

It’s the fear, in the end, that coaxes a fugu-eater into a strange psychological state. In order to eat fugu at all, one finds herself narrowing focus to eliminate any projection towards the future (where death might lie) or into the past (where one might have avoided the predicament entirely). As if to pin down a sheet of paper fluttering in the wind, you focus on the supple texture of the meat, how the vinegar accentuates a slight saline quality. You line up every bone you pull from your lips on the edge of your plate, the only mark of time passing.

In forty-eight hours, I’d be home again and back to the rhythm of my life in New York, worrying over the weight I’d gained on my trip and how to put into words what I’d discovered in Japan. But for now, the server was bringing me the final course. I was confused as she cracked an egg into a small bowl filled with rice then whisked the mixture into the water leftover from the last course. I waited, looking over my shoulder for the rest of the fugu. A plate of fried bones? Two quivering eyes? But then she ladled a thick porridge into a small bowl and topped it with chives. I ate a spoonful and understood in tasting that fine, delicate broth the point of the ceremony: the entire fish, from head to tail, redolent in one bite. The subtleties and radiant comfort of this bowl of soup were astounding in light of the fear that presided over the previous courses. Without wandering the territory before, there would be no way to appreciate this final gesture, the gathering of the whole.