Sweet Medicine

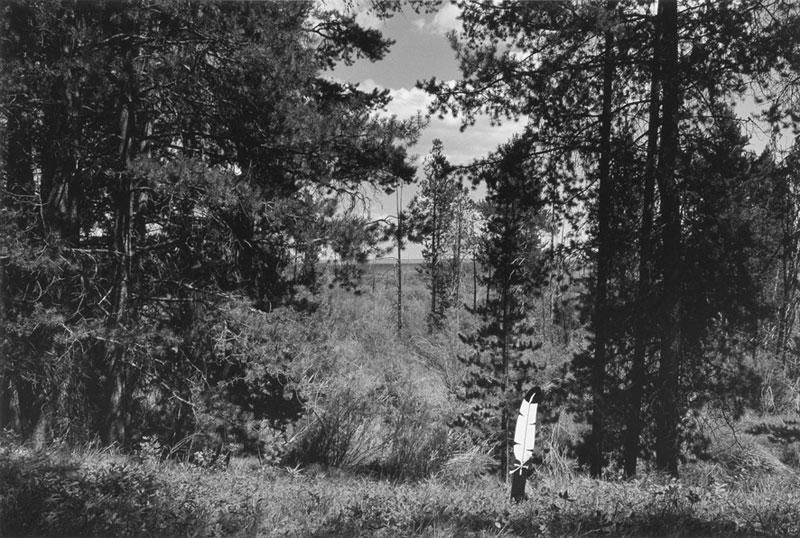

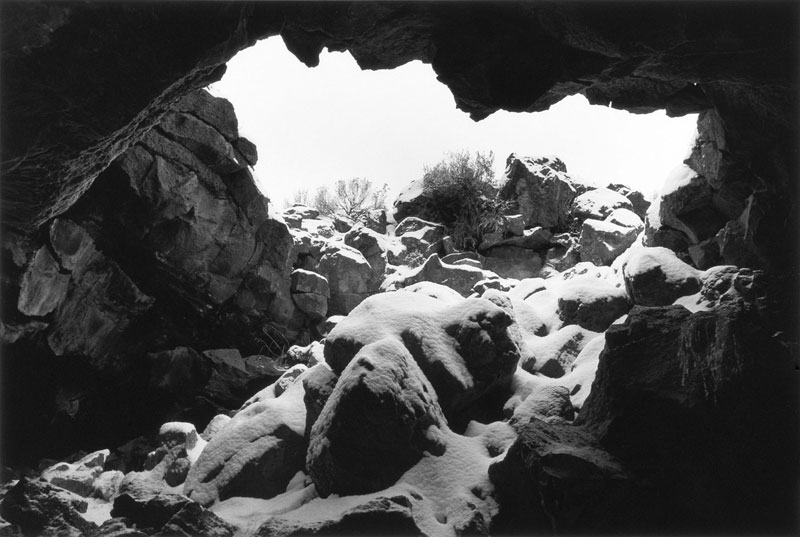

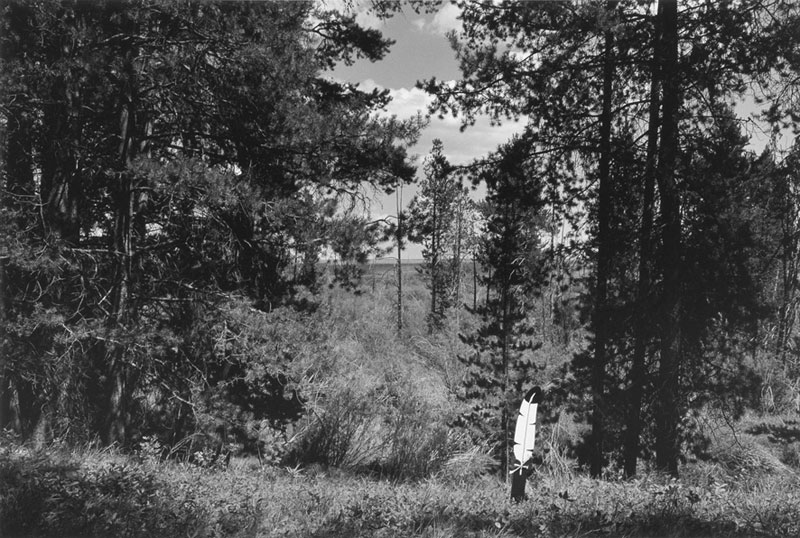

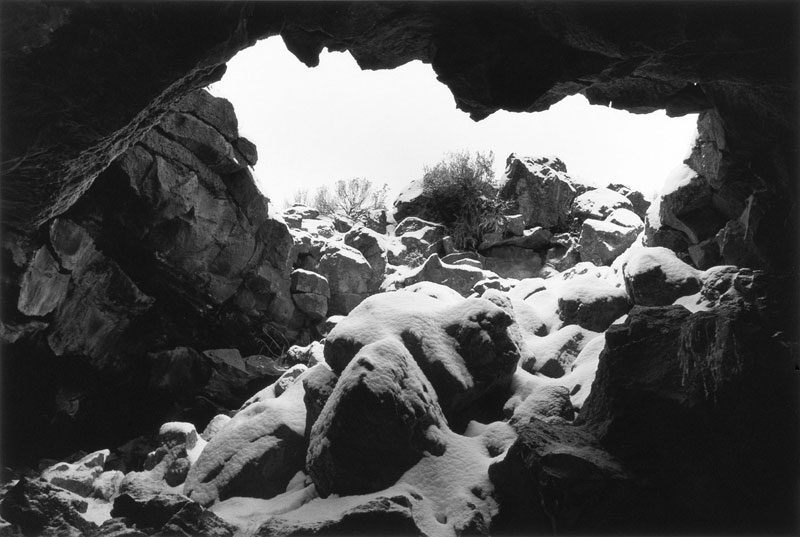

Drex Brooks photographs historical sites where conflict between Native Americans and white settlers occurred. The stillness of these overgrown or repopulated sites reminds us of what’s been forgotten and what’s missing.

Interview by Nicole Pasulka

What is your relationship to Native American people and culture?

I grew up around Indian reservations and was aware of conditions on the rez and of the prevailing white attitudes at the time. I also read all the books I could find about Indians—Cochise, Sitting Bull, etc.—and was enamored of the beauty of the life and people portrayed in those books. I couldn’t quite put those histories together with what I was taught in school and what I was seeing and hearing about Indians on the reservation. I wasn’t aware of all that happened between the cultures, so I guess the photographic work I did was my way of learning more. Continue reading ↓

A book of Drex Brooks’s photographs, Sweet Medicine: Sites of Indian Massacres, Battlefields, and Treaties, was published in 1995. Some of those photographs are in this exhibition at the Amon Carter Museum. He received a National Endowment for the Arts Visual Artist Fellowship in 1988 and 1992 in support of the “Sweet Medicine” project. All images appear courtesy of the Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas; copyright © Drex Brooks, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

How did photography help you to learn more? Did you end up doing research about the history of conflict between Native Americans and whites?

While living in Denver, I became curious about a little red mark with the title of Sand Creek massacre on the Colorado road map, so I went there to look around. The next week I went back with a camera. I probably drove out there four or five times to photograph, and I also started reading about the place and what happened there. Then, from my reading, I learned about other sites and started taking longer trips to Nebraska, and to Wyoming. Then it became a project that pretty much took up the next five years of my life. There was a lot of research, a lot of map-reading trying to find places discussed in historical accounts, a lot of asking local people for directions. A few places were historical sites that were well marked, but most were not. Some were quite obscure and difficult to locate; it was a strange sort of treasure hunt.

The locations of these photographs are all sites where conflict between Native Americans and whites occurred. Where across the country did you actually photograph?

For this project, I photographed in all of the 48 adjoining states, somewhat more in the western U.S.

How did these locations end up becoming personally important to you?

The significance for me was on several levels, but mostly it was the obscurity of the sites and the lack of accurate cultural memory regarding the events that happened in places that are now parking lots, playgrounds, garbage dumps, etc. I found the sites and tried to work with what was there—landscapes, people, buildings—and I enjoyed that aspect of the project.

Who is Sweet Medicine?

Sweet Medicine is a sacred prophet in Cheyenne oral history. He spoke of the dire consequences for the Cheyenne of the coming of the white people.

In your opinion, what has been most egregiously overlooked or mistaken about the history and the present lives of Native Americans?

That’s a big question! Here’s some information put out by an organization called the Center for Community Change: According to the 2000 census, there were 4.1 million American Indians, including Alaska Natives. Native Americans remain the poorest minority group in the nation. The poverty rate among Indian people is 25.9 percent, compared to the national rate of 11.3 percent. Associated with this poverty are poor health conditions, lack of affordable and decent housing, substandard education, a critical lack of jobs, and a host of other barriers that keep most Native American communities isolated and economically distressed. The Indian unemployment rate was 46 percent in mid-2004. While a handful of tribes have achieved a measure of success, the vast majority [of these tribes] is in serious need of jobs, economic growth strategies, and policy solutions that can counteract the results of decades of oppression.

When I see “social landscape” photography, or photography that focuses on rural settings and communities, I’m always interested in the photographer’s influences. What other photographers have influenced your work?

Another big question! There are too many to name, although Robert Adams, Lee Friedlander, and the FSA [Farm Security Administration] photographers come to mind right now.