Most journalists are restless voyeurs who see the warts on the world, the imperfections in people and places. Gloom is their game, the spectacle their passion, normality their nemesis. —Gay Talese

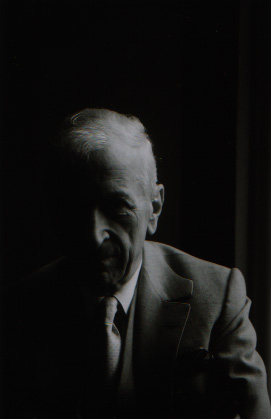

Beginning his career at the sports desk, Gay Talese was a reporter for the New York Times from 1956 to 1965. He went on to write for numerous national publications including Time, Esquire, the New Yorker, and Harper’s Magazine. Among his 11 books are Kingdom and the Power, Honor Thy Father, Thy Neighbor’s Wife, Unto the Sons, The Bridge, and his long-in-the-making memoir, A Writer’s Life. Also recently published, The Gay Talese Reader includes some of his seminal journalism, such as “The Silent Season of the Hero” on Joe DiMaggio, as well as his 1966 Esquire magazine article on Frank Sinatra, “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” which Esquire called arguably “one of the most influential American magazine articles of all time,” focusing not just on Sinatra himself but also on Talese’s pursuit of his subject. Gay Talese lives with his wife, Nan, in New York City and Ocean Park, N.J.

In what follows, Gay Talese, in his loquacious, inimitable manner talks about his approach to reporting and writing that led to his association with the launch of so-called New Journalism. And there is a little bit, here and there, about him.

Robert Birnbaum: I know you are an avid Yankee fan. Is there a story that you think sportswriters are missing about the Yankees and the Red Sox?

Gay Talese: I could come up with 50 stories that I am thinking about.

RB: Seriously?

GT: I have, without being immodest to you or anyone, a way of looking at a subject—it could be the Yankees, it could be a tree in Boston—where I would say to myself, There is another way of looking at this tree, or this ballgame or these players. Yes, indeed. Do you want a whole series of story ideas? No.

RB: In A Writer’s Life, you are sitting at a restaurant and you see a man eating a fish—then the paragraph continues on for another page or so—it reminded me of when we were in high school biology and you are shown a drop of water under a microscope—

GT: Yeah, it’s the imagination of the nonfiction writer. It is nonfiction we are dealing with, as you know—it’s what can be—the way of seeing is very private but can be very creative, and you can take any assignment, any subject, and write about it if you can see it in a vividly descriptive or instructive way. And as you mentioned, I am a restaurant-goer. I go to restaurants a lot. I work alone all day. At night I like to have something to do where I am around people and a restaurant is the best excuse of being around people. I don’t care about the food that much. I care about the atmosphere. Restaurants are a wonderful escape for me. And are for a lot of people. People go to restaurants for so many different reasons. To court a girl, to make some deal. Maybe to talk to some lawyer about how to get an alimony settlement better than they got last week. What I have done since I was 50 years younger than I am now—which is to say 24; now I am 74—I think what I do is write nonfiction as if it were fiction. On the other hand, it is clearly, verifiably factual—but it is a story. It is storytelling. It isn’t telling you a story of somebody you already know. It is, more often than not, somebody you do not know. Or if it is somebody that you do know that I am writing about, it will be something that you don’t know about that person. It is a way of seeing, a way of going about the process of research. It might be interviewing, or it might be hanging around. For example, many colleges in their writing programs teach some of my work. What they often do is teach something like “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” something I wrote when I was 25 years younger or more. That isn’t about Frank Sinatra at all. I didn’t even talk to Frank Sinatra—

RB: [laughs]

GT: What I did was I hung around people who hung around Sinatra. You mentioned in reference to the book I have out now, “You go to a restaurant and you see a guy having a certain fish for dinner.” And he is eating the fish, and across the room I am watching him from another table eating the fish. And I am thinking, Now let’s take this fish and do it in reverse. Instead of the fish in his mouth, let’s take it out of his mouth and move the whole process of that fish back to the time when it was in the kitchen being prepared by the chef. And before it was in the kitchen with the chef being cooked to a certain specification by the diner, it was in a box of ice and before it was in a box of ice, it was being transported by plane to a New York airport, thence to the Fulton Fish Market. But before that the darned fish was in the water somewhere being caught by some disgruntled fisherman who was in water that he shouldn’t have been in—

RB: [chuckles]

You have to do what you have to do with what you see, and you have a way of seeing people and caring about people and describing your city, describing what you see. It is your realm, your world. And you do it. Nobody is going to like it, necessarily, but you do it.

GT: And he is having trouble with his wife and he is on his miserable ship off Newfoundland somewhere and this awful guy, this awful guy, is a fisherman now, and he is grousing to himself when he catches all these damned fish and a whole process is going back into the personalities of the people who catch fish, the people who are trolling—watching fisherman in places they shouldn’t be because they are in lawless waters. All these things that can rise to the mind of a creative person just by virtue of being across the table from a person devouring a piece of tuna. It’s all traceable in a factual sense if you move backward. But it also is something that many, many people sitting in a restaurant, idling their time over their own dinner wouldn’t have the curiosity—it’s all about curiosity.

RB: A young writer couldn’t get away with this approach today—because editors want stories that they already know.

GT: I don’t believe it. When I was 24, they were saying the same thing. I teach courses and the writers say, “Oh, I don’t think you’d get these stories in the paper today as you did back when you were doing this thing, back in 1958, let’s say.” In 1958 I was having trouble getting in the paper. In 2006 you’ll have trouble. But that doesn’t mean that you can’t do it. You are not going to bat a thousand. You may not even be a .500 hitter. Let’s say you get four out of 10—but it’s worth it. Because those four, if you get four good ones, those stories are stories that you will like to read a month from now. Or maybe a year from now. The stories that you have trouble getting in the paper are difficult because they do not fit the conventional mold of the rounded-headed editor. And if you wanted to play games with the editors you are going to wind up being an editor, someday being miserable.

RB: [laughs]

GT: Better that you should take the chance of trying something that is close to your heart, you think is what you want to write, and if they do not publish it, put it in your drawer. But maybe another day will come and you will find a place to put that. You will take it out of your drawer and do something else with it. I wrote a whole book when I was 24, I wrote a book called New York: A Serendipiter’s Journey. It was my first published work. It was a slender volume and I got a photographer friend to illustrate some of those stories.

RB: Bruce Davidson?

GT: No. It was Marvin Lichtner. Bruce did another book called The Bridge. And these stories mainly, were stories that had been rejected by the New York Times city editor. Why? Because they didn’t seem to have any meaning. They didn’t make any sense. They weren’t relevant. And I said, “By whose standard not relevant?” I am writing about people who are alive in the city of New York during mid-20th-century America. And these people are like a character in a play or they are figures in a short story or a novel. They are the sort of people that Arthur Miller wrote about when he wrote Death of a Salesman. Don’t tell me Willy Loman is not significant. Don’t tell me Willy Loman isn’t important. Yes, he is not a great salesman but I know a lot of people who are not great salesmen, who weren’t newsworthy and don’t have a face that people recognized. But they could be given a face by the writer, they could be brought alive like Mr. Willy Loman is brought alive, not only for American audiences but all over the world. You find Willy Loman in China, you find him in India. In New Zealand. This play by Miller, such a play that it is an international play. And what is it about? A guy that didn’t make it. You know, his wife says to his children, “Attention must be paid.” Well, I think attention must be paid, as the great Arthur Miller said, in his play, to a lot of people who aren’t having any attention paid to them. So the city editor tells me, “Oh, we aren’t going to print that, they spiked it.” You know what “spiked” means. Well, you let it be spiked and pull it off the spike and you think about it and there will come a day that attention must be paid and you will get it printed. So I say to the student of 2006, no less than the student I used to be in 1958, you have to do what you have to do with what you see, and you have a way of seeing people and caring about people and describing your city, describing what you see. It is your realm, your world. And you do it. Nobody is going to like it, necessarily, but you do it.

RB: You say this in the light of the fact that early in the book you talk about watching the Women’s World Cup soccer finals, and once you bring it up, it does seem interesting—what becomes of Liu Ying [the Chinese player who missed the championship-deciding free kick]? And you contact Norman Pearlstine, editorial director—

GT: You have to set it up better. We are watching television. What’s the year? It’s 1999. Who cares? Well, in July of ’99, it was the Rose Bowl and what mattered? 90,000 people showed up. For what? Soccer. What kind? Women’s soccer. Not on your life would I buy a ticket to that.

RB: [laughs]

In nonfiction, which is what I am a practitioner of, you can write these kind of stories that are not novels, that are not plays, but are real. You don’t have to fake the name. Use the name! You don’t have to make anything up—because life is fantastic. Ordinary life is extraordinary. It is. You know this.

GT: Not on your life. Who wants to see women’s soccer? Not me. I don’t even like soccer. I am an American and like most Americans don’t understand it and don’t care about it. Yes there is a little group of soccer aficionados, but I am not one of them. All I am doing is, in July of ’99 with nothing better to do, being a little bit awkward about my work because I wasn’t getting a chapter moving along that I was working on. I took the day off, Saturday, and I watched this ridiculous thing called soccer. And women. What amazed me was all these people who went to the game, filling the Rose Bowl, which is a pretty big arena. Moreover it was on ABC national TV, this women’s soccer match. And it was involving the women of China versus the women of the U.S. That didn’t matter much to me except I was curious about Chinese women. People in China are our enemies, so the China-bashers in Washington will have us believe. Anyway, I was watching this with some curiosity only because it was the crowded stadium, national television—I wondered who would the put this on, what the ratings point to be. And then the game went on and on and on. It was boring as hell. It was nil-nil. It lasted three hours. And the only thing I remember, after the game was over and there was an overtime, was that they had penalty kicks. Maybe you know, but I didn’t know about penalty kicks that decide the game. They take turns, five from each side, each one kicks. Everyone made it except for one Chinese girl. I started thinking. Wow, here’s a girl, and she is only 24—she has been in front of 90,000 people. She probably comes from some little village where she has never had any attention paid to her anyway. In fact in China, female children are frequently aborted. And now she has to get on the plane and fly all the way back to China. Long trip. All these teammates silent, probably crying along the way. She messed up. China lost, all because of her. She goes back to this nation of 1.3 billion people—22 percent of the world’s population lives in China. Here this little girl gets off the plane, somewhere in Beijing or Shanghai or wherever, and she has to go back to her village, her tearful mother is probably meeting her at the airport. So are the other mothers of the soccer women on the team, 22, 25 people. Goes back to her village. Goes to sleep on a straw mattress probably. And has to wake up to a new day in China remembering that not too long ago, maybe three days ago, she was in the middle of the sunny Rose Bowl in Pasadena, Calif. Now how does this girl get through that week? And what does she do and what do the people say to her? And what does it say about China? What does that say? What does it say about being a girl in the public eye? Then you go back to the reality of your home country and having to relive this moment, and that’s not a sports piece. That’s not what I am interested in. What does it say when you stay with such a girl for the next two or three months? And you see the world as she sees it. Meaning her homeland. It’s an interesting way, through the young woman’s eyes, to see China—as opposed to seeing Henry Kissinger go over there and give you some canned speech at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York about “China Today?” Who cares about Kissinger? It’s a different approach

RB: As a matter of fact, tomorrow I talk to Peter Hessler—

GT: I know him.

RB: He’s writes from China for the New Yorker. And his book Oracle Bones is very much the approach to China that you are espousing.

GT: I know Peter and he wrote a beautiful book called River Town: Two Years on the Yangtze, which I read with great interest, and I met him in China a couple of times. He does wonderful pieces for the New Yorker. But this is the point—this is just one character—you mentioned the fish earlier, you trace the fish, you trace the soccer maiden, and what do you see? You see the whole vista, the world as she sees it and feels it. And it’s a new take on China, a new way of looking. A way of seeing. S-E-E-I-N-G as opposed to fishing. And seeing the sea. It’s a way of looking, of reporting; a way of writing and the book is full of stories like that.

RB: So you propose this with great enthusiasm to—

GT:—the big boss, the maven at Time Warner.

RB: It doesn’t get any interest.

GT: It doesn’t go.

RB: You put the story aside for a while and it haunts you.

GT: That’s right. It’s like I did when I was 50 years younger. The same darned thing. I have been doing the same thing for 50 years. I’m thinking the same way, reporting the same way. I look story, story, story. I am not looking to cover the Senate. I don’t care about being a political reporter. I don’t care about current events. I care about stories. Like a Willy Loman is a story. Whether it’s 1953 on Broadway or 1961 in Chicago or 2006 in Beijing. It’s the story, the same story—characters.

RB: Correct me if I am wrong. I get the sense that in the end, when you finally track down Liu Ying, you were disappointed—

GT: No, no. No! You know what it’s like. You go after somebody to use their eyes to see something else. When I went to China, it was with the excuse to start with her and then you move with her through time and then you meet her mother and then you meet her grandmother. And you meet the people of the village, the people who live in this old backward part of China, 15th-century China. 15th-century China is only a mile and a half away from some towering new apartment house, some glass skyscraper preparing for the 2008 Olympics. What it is is using your Willy Loman character, your nobody, your everyman. Philip Roth has a novel called Everyman. It’s a novel about nobody. He didn’t even use his name. In nonfiction, which is what I am a practitioner of, you can write these kind of stories that are not novels, that are not plays, but are real. You don’t have to fake the name. Use the name! You don’t have to make anything up—because life is fantastic. Ordinary life is extraordinary. It is. You know this. It’s just a matter of being able to see it, to see it and being able to write it.

RB: I had talked recently to someone who had written about Harvard’s 1920 homosexual witch hunt—William Wright, who is a journalist—and said in the course of our chat, “There are a lot of great novels but not as many great works of nonfiction.” David Shields took umbrage—he had written on this topic for the Believer and sent me a list. What do you think, are there more great works of fiction than nonfiction?

GT: I am afraid yes, because there aren’t people who work hard enough as nonfiction writers. What they do is they want the story to be obvious to the reader. And they account for a majority of nonfiction books, they that wrote about famous or well-known people or newsworthy people. They will write about a movie star, they will write about a president. They will write about a dictator. Chairman Mao instead of the little soccer woman I’d write about. Or they will write about the Harry Truman years or Bob De Niro. OK? That’s fine, but I wouldn’t want to write about Bob De Niro, wouldn’t want to write about Harry Truman. You can let historians do that or movie critics write books about Robert De Niro. Or whomever. What I want to write about are the people that you wouldn’t read about except that you like the writing that I do. I have always read the fiction writers for my—when I was a kid growing up, I read the fiction writers because they were storytellers. What I wanted to do was break from their company when it came to writing—I wanted to be a storyteller. With all of the qualities of the scene-setting, the dialogue, the place and time and the time and place in which your characters move. And I want to move with the characters, move with them and describe the world in which they are living. And I want to aspire to achieve whatever is literary in a graceful sense by great proponents of fiction, be they William Faulkner, be they John Cheever, be they Philip Roth or I don’t care who, but make it clear to the reader: Yes, this is a story; yes, these are people you are reading about, but they are real. They are real. This is not made-up. We are not faking the facts. We are doing a lot of reading and we are taking a lot of time. Thirteen years I took on this last book. And it’s not about one person. I, just like some of the major novelists, have a lot of characters; Tolstoy had a lot of characters. It’s not about one guy. Dostoevsky, even Fitzgerald—I mean The Great Gatsby isn’t just one character. There are a lot of wonderful characters in this. And so in my books there are many characters in this book: in Unto the Sons there are a lot, in Honor Thy Father, in The Kingdom and the Power, The Bridge, many characters. I have a whole stage filled with people and they interact.

RB: Where do you place Capote’s In Cold Blood?

GT: Excellent. He is so famous now because of the movie [Capote, released in 2005], but he has always, for people who care about writing, had a high place in my mind, as much as my whole generation, who came of age when Capote was just establishing himself. I knew him a little bit. I wasn’t his best friend, but I certainly saw him a lot in New York and also in California. But where does he sit? He was both a good writer—

RB: Was In Cold Blood a break with the past?

GT: It wasn’t a break with Capote because he always wrote, whether he was writing fiction or nonfiction—he did both. Speaking of movie people, he wrote a terrific piece on Marlon Brando that appeared in the New Yorker originally and when I started reading Capote he was a short-story writer. I’d read his stories but when he wrote [his unfinished novel] Answered Prayers, there’s a section of it called the Cote Basque, and he writes about real people sitting in this famous restaurant. The owner of the restaurant was Henri Soleil, a Frenchman, and there is a conversation that I quote in A Writer’s Life. He’s terrific. In Cold Blood was a stellar example of nonfiction done within the style that I adhere to, which is the fictional style. They’re real people—there are many characters in that Capote book. It’s about the family that gets butchered. It’s about the two murderers, about their execution, and the law-enforcement people. There is a whole cast of characters.

RB: Harper Lee.

GT: Harper Lee is not to be excluded, of course.

RB: Were there alternative titles for your book?

GT: Yes there were. A Writer’s Life was the chosen title of my editor, Jon Siegel of Knopf. I didn’t have a title. It was called An Untitled Manuscript when I turned it in. For my own identity, since the first person I wrote about was the soccer woman from China and I called her “soccer maiden,” I was putting Soccer Maiden just as an identity for the manuscript, but it wasn’t ever going to be the title. I don’t get my titles—other people suggest them. I mention my editor gets credit for this title: I wrote a book on a Mafia family I hung out with—it was called Honor Thy Father. It wasn’t my title. It was the wife of the Mafia guy that I knew, Bill Bonanno. His father was the Godfather of the Bonanno family. I met them both of course. But the wife said of her husband, my friend Bill Bonanno, “He goes to jail all the time, to honor his father, to stay in the family business.” How awful. “That’s a good title.” I said. And that became the working title—but it was Rosalie Bonanno who told me about him. The Kingdom and the Power, about the New York Times. It wasn’t my title—somebody thought, that’s what you are writing about, this kingdom, this old-fashioned business, family business, dynasty, feudal in a way. I didn’t even think of Unto the Sons, the book about [Talese’s family’s immigration to America]. Again it was Jon Siegel. I have had the same editor at Knopf the last two books, which is to say about two decades. Each book takes about a decade to do.

RB: And how does he edit you?

Look, if you want to make your living chopping people up, you will find an audience. You will, but it’s not me.

GT: I’ll tell you exactly. I work extremely hard so that he will not have to work extremely hard. I write and rewrite and rewrite and write and like to turn in what I think is finished work. Which doesn’t mean that he won’t have his opinions. He will take my manuscript and read and he will call me and say, “Gay, let’s have lunch.” Or, “Come in and see me. I have read your manuscript. I think it’s very good, but I have some suggestions.” So I go in the office. “Jon, what are your suggestions?” “You know, I think you are perhaps telling a bit more than the reader wants to know about this restaurant where this guy eats this fish. Now that’s one long, long sentence. You think you may want to cut it up?” And I’ll say, “Jon, did you have to read it twice?” He said, “As a matter of fact, no, I didn’t.” “All right, now how do you really want to deal with the character of John Bobbitt? You have this guy—this poor Marine who lost his penis. Now, do you want to go into such detail about the surgery when the wife chopped off the penis? Do you really want to deal with the neurological and the urological surgeons to the degree that you have because you are in the hospital room and you describe the operation and the reattachment?” I said to Jon, “I think readers are interested.” “Well. In great numbers?” “I’m not sure that readers in great numbers are interested. But it is interesting detail and there are certainly a few readers that might appreciate it. Let me think about it.” So, back and forth, that’s what he does. He is your first reader, he or she, the editor, whoever you have is your first reader and perhaps your first critic. And you can take what they advise. My wife is an editor. My wife believed her author James Frey. You have heard of him.

RB: Uh-huh.

GT: And it turned out he lied to her. He didn’t have these problems as an addict, as a junkie, whatever. He didn’t go to jail for as long as he said he did. A lot of things—she believed him and she has been a publisher and editor for more than 40 years.

RB: Why would you not believe him?

GT: That’s exactly what I say. You have to believe him. If you can’t believe your writers—and then the criticism is, “Well, the book publishers have to get fact-checkers.” I said that the New York Times didn’t fact-check Jayson Blair, and he wrote 35 articles.

RB: Stephen Glass at the New Republic, Mike Barnicle at the Boston Globe. I read two articles—do you read your reviews?

GT: If they send them to me. I am on the road.

RB: [I’m referring to] Chip McGrath’s piece in the New York Times and Kurt Anderson in the New York Times Book Review or New York magazine

GT: He [Kurt Anderson] used to work there. He did a hatchet job. It’s probably the work of the editor at the Times. You asked about editors—if you edit a book review like the New York Times or any book review, and you know when you are matching up author with critic—you can pretty much predict what you are going to get. If you want to have a sympathetic reviewer or at least one that is fair-minded, what you do is get a person of real accomplishment to be the reviewer. For example, if you get someone who is an outstanding writer or a person of some prominence as a writer and they review an equally prominent writer, you are going to get a critic or reviewer that’s going to be fair-minded. But if you get somebody who probably has a chip on their shoulder and probably doesn’t like the fact that I have had some attention paid to my work, to quote Mr. Miller, maybe they want to call attention to themselves by carving me up in public. And that’s happened to me before. It happens to all people, almost, at one time or another. So I got a man, Chip McGrath, who doesn’t have chip on his shoulder, and then the other guy, Kurt Anderson, who is a second-rate hack—

RB: [laughs]

GT: A guy that you never heard of—

RB: A former Spy magazine editor and New York magazine, and he wrote a novel called Turn of the Century—

GT: Did you read it?

RB: No.

GT: Why not?

RB: I started it, and it was not something I wanted to read more of; it was not readable to me—

GT: Put that on your tape.

RB: The tape is rolling.

GT: So this guy is disappointed. I didn’t read the book that you mentioned. I read fiction—I didn’t read him—a guy that started Spy magazine already is on my “no read” list. This is a guy who took advantage of other people’s privacy and is probably mocking them. He is into the vilification of people.

RB: I enjoyed Spy magazine.

GT: Did you? Well, I—

RB: Especially for the description of Donald Trump as “a short-fingered vulgarian.” I have since found that phrase useful—

GT: Look, if you want to make your living chopping people up, you will find an audience. You will, but it’s not me.

RB: My sense is that the difference between McGrath and Anderson is that McGrath is a writer besides being a journalist, and—

GT: And has been an editor.

RB: Kurt Anderson is a media person and he functions as media critic and pundit.

GT: Does he?

RB: That’s my impression.

GT: I don’t know that. But he didn’t have a clue of what I was doing.

RB: Right, and I bring up the contrast between the two men because in a way it’s a matter of taste. Some people want to know the information that you thrive on and like the prose, and some—

GT: Well, listen. You ask me who my favorite fiction writer is of my contemporaries, I’d say Philip Roth. Now Philip Roth was chopped up by Michiko Kakutani on Everyman. Here’s this woman, she bombed this thing—it was Pearl Harbor, for Christ’s sake. Michiko does a kamikaze, whole thing on Roth. On the other hand a week later the same book by Roth is praised [in the New York Times]. This guy Anderson, who is an unsuccessful writer, maybe he will be, someday, successful, and then he may have other thoughts about writing, but he doesn’t seem to know very much now. I knew about him—when he was doing Spy magazine. I have a friend who just died—I went to his funeral just yesterday. A.M. Rosenthal? His wife is English, Shirley Lord. And these guys, Kurt Anderson and Graydon Carter, when they had that magazine called Spy, would rip up the wife of Rosenthal, every week. She was a novelist and I am not saying that she was better than Emily Dickinson—I am merely saying that every week they’d chop her up calling her a “dirty book writer, dirty book writer.” Constantly. So they got their point across. But every week they’d pick on her because they didn’t like Rosenthal. And they’d beat up on the wife. And I [thought], what a bunch of wretched guys these are. One of them was Anderson. So 25 years later, here’s the guy that reviews my book. Now who’s the guy? Sam Tanenhaus, the book reviews editor, wants to have sparks. He knew how to match people up. It’s like if you have a dating bureau. You know who is not going to like one another and who is compatible. And who you might have a second date with. Well, this is the luck of the draw. But you can’t ever predict.

RB: Book reviewing is a degraded enterprise in this country, for among other reasons than the matchmaking you suggest. Let’s move on to something more pleasant.

GT: Anything.

RB: [Former world Heavyweight Champion] Floyd Patterson died recently—

GT: Yeah two friends in one day it seems: Patterson and then newspaper great A.M. Rosenthal. I was a pallbearer at the Rosenthal thing and many people that worked on the paper, like Bernard Kalb, was a pallbearer. Ed Koch was a pallbearer and Joe Lelyveld used to be executive editor. It was like real reunion of old-timers—like an old-timers’ day. It was centered around the great Abe Rosenthal.

RB: [laughs] That would be the bittersweet part of your generation’s history—you will meet at funerals.

GT: Well, yeah, there were younger guys there. Tom Friedman and many others. But Patterson, back to the prizefighter, he really was one fighter that I knew who could describe what it is like to be a fighter. If you talked to Muhammad Ali, of course, he was great guy when he was young because he was the most noisy of fighters, but not always the most articulate, so consumed with himself as he was. I had a sad experience with Ali in 1997. I got an assignment from the Nation, Victor Navasky was the editor, and he said, “Would you like to do a piece on Muhammad Ali meeting Fidel Castro in Cuba?” I said, “Are you crazy? Of course I would love to do that piece.” “OK, you have to go tomorrow.” I said “Sure.” I live in New York and I went to Florida. There is a plane leaving Miami [for Havana]—

RB: At three o’ clock in the morning

GT: A little charter plane. Muhammad Ali is going to be there with some people who were on a humanitarian mission. And then I went to Havana and then it turns out I couldn’t talk to Ali. Because Parkinson’s had taken his whole way of communication away. So I had to deal with the story from other points of view. Which is OK, it’s how I did it when I wrote about Sinatra. It was the same thing. So it really wasn’t so bad. I would have liked to talk with Ali, but he is not able to make himself understood.

RB: In this book you gave Floyd Patterson’s description of what it is to be knocked out, right? At first it feels good and then—

GT: He was great, that’s great stuff, in this book.

RB: What a gentle soul. I grew up listening to the Liston-Patterson, Ali-Patterson, and Ali-Liston fights. I think the Patterson-Liston was at Comiskey Park in Chicago.

GT: I think so. Wait a minute, I was there in ’62 or ’63. It might have been—you know who I went with to that fight? I went with James Baldwin because he was living in New York. I knew James years before. But this was ’62 and he was doing a piece on the fight for Nugget magazine. Nugget was owned by Playboy, I think.

RB: It was a bit racier, right?

GT: Maybe it was. But I know that he was there and I didn’t know that he was going to be there. I said, “Hey, what are you doing there.” He told me. I said I covering this for the Times, I had left sports but I had bid on the assignment and when it was Patterson, I wanted to cover it. I was so interested in him as a person as well as a fighter. It wasn’t much of a fight. He was knocked out in the second round. But it was in—Baldwin was there and I drove out with Jimmy to this camp before the fight, outside the city, somewhere in Illinois, and we had fun. I had a rented car and he, Baldwin brought two of his novels to give to Patterson, inscribed them. Baldwin was an exceedingly zany and brilliant, brilliant writer. I quote something he wrote in this book of mine. There is a section having to do with interracial marriage. And I quoted from The Fire Next Time, his famous essay. And he talked about, “I don’t want to marry your sister. “ I hate to try to quote—I am not, I am just paraphrasing but something along the lines: If we want to marry it’s our choice and maybe if she doesn’t raise me to her level, maybe I will raise her to mine. Or something like that. God, I wish I had it in front of me to read to you, but sometimes you go out on an assignment—a prize fight and you meet somebody—Baldwin, James Baldwin, and you think, “Wow I am certainly glad I made the trip.”

RB: Wouldn’t it be about time for a Baldwin renaissance?

GT: Yeah, it is time. They go in and out. It’s like with Capote—I hope it doesn’t take a movie to do it. But there was a time when all of the works of William Faulkner were out of print. Out of print! Nobody thought about him. There is a time when—Fitzgerald died in obscurity. Herman Melville, there is a beautiful biography out now.

RB: Andrew Delbanco’s.

I had an assignment with Tina Brown. She wanted a woman’s point of view, the woman who chopped off the penis to be the main story. And I was interested in the man who lost his penis—two perspectives here. The problem I had, which is a novel experience for me, was that the woman that chopped off the penis had a Hollywood agent.

GT: Melville died in poverty. You just don’t know, and then you come back. You just don’t know what readership there is.

RB: Baldwin was equally talented as a novelist and essayist and journalist.

GT: I agree with you. He was a great writer. And I liked his fiction more than some of the critics—the critics knocked his fiction, especially the novels. But, boy, what a voice he had as a fiction or nonfiction writer. And of course, The Fire Next Time—you could read it now and you’d become fired up. You sure do.

RB: Has anyone written anything, a decent obituary of Floyd Patterson? Did I miss it?

GT: There was an obituary but not a decent one. Because the people didn’t know him. I knew him because I hung around with him for years. When he first came up, I was just coming up. I was coming up in journalism in the middle 1950s and my first job, since there was an opening in the sports department—the New York Times—and the guy that was coming up was this light heavyweight named Floyd Patterson. I saw him have a couple of fights, had a few interviews after the fights and then I asked to see him longer. I wanted to do a little magazine piece for the New York Times Magazine. And then I did another interview and another interview and then I got to know him a little bit, and then many, many years later after he had lost his title to Sonny Liston—he’d lost it before to a Swede named—

RB: Ingmar Johansson.

GT: And then he won it back. I saw all those fights and these fights you see—I mentioned Baldwin before, but you’d see a lot of novelists hanging around fights. I used to meet Budd Schulberg at every fight. Norman Mailer was almost always there. George Plimpton was usually there.

RB: Joyce Carol Oates, did you see her?

GT: She is interesting. She really is interesting. And she has written really well about prizefighting. She didn’t know Patterson. I guess I probably knew him better than anyone. I didn’t know Sonny Liston as well as Plimpton and Mailer [did] of course. Though I wrote about him.

RB: Do you know Nick Tosches’s book on Liston?

GT: You know, I know Nick Tosches and he is a wonderful writer. And I might have read a little bit—Sonny Liston was a tragic, tragic, menacing man—not a nice person, but of course he didn’t have chance to know what nice was. Patterson for some reason was a very different man. I didn’t know any other fighters other then the heavyweights. I knew a fighter—a welterweight and then middleweight champion and then a light heavyweight champion. His name was Jose Torres and he was a Puerto Rican. I knew him very well: I used to hang around and have dinner with him, met his wife, hung around in good and bad days in his life and greatly admire him—he’s still around. He’s probably 64 years old now.

RB: Is he still cogent and lucid?

GT: He is, he is. I thought Patterson was going to—

RB: He took some beatings.

GT: He did. I thought he was going to survive, and I’ll tell you why. He got knocked down a lot and he didn’t take much punishment. But he always got up. He was knocked down more than any fighter, but he got up more than any fighter and that probably is why he didn’t have it all together at the end, the last four or five years of his life.

RB: Somewhere in the book you mention that in doing the book, it took you 12 years to do this book. Was that part of the problem, that you didn’t know what the story was?

GT: No, it was because I wanted to write about stories and I wanted the stories to be integrated—

RB: Didn’t know what your story was.

GT: I don’t think that I even have a story. My story is that I am a storyteller. And in order to write about a writer, you can’t write just me, me, me, me. I remember one of my favorite fiction writers has always been Graham Greene. When he did an autobiography, or maybe a biography was done—don’t remember which—it wasn’t much of a book because the man was creative, and the people he knew were the people he created. In my case, it isn’t that so much. I wanted to write about the creative process, the timing process, curiosity and people who were difficult to get to, and how you got to them. How to move them? I wanted to write about the moves of the writer, the process of writing. How to, step-by-step, collect information and how you organize it. But I also wanted to write about me, and there is a lot about me in this book, about my childhood, about my days as a journalist at the New York Times—

RB: And what your office looks like and your computers—

GT: My computers. I write about my flashbacks when I was in the Army. I go back to Italy to see the poverty of my father’s village in Calabria in southern Italy, I write about my covering the civil rights movement during the time of Martin Luther King’s march from Selma to Montgomery. There is more—there is plenty about me in there. But it’s a balance. It’s not all about—it’s not as if I am Winston Churchill and I have to write three volumes about Winston Churchill’s boyhood, Winston Churchill in—I wanted to write about writing and to write about a writer and write about the goods and the bads of writing. Writing about people that give you the runaround and how you circumvent that. The difficulty of dealing with Lorena Bobbitt, of dealing with editors. You mention editors and critics: I had an assignment with Tina Brown. She wanted a woman’s point of view, the woman who chopped off the penis to be the main story. And I was interested in the man who lost his penis—two perspectives here. The problem I had, which is a novel experience for me, was that the woman that chopped off the penis had a Hollywood agent—

RB: [laughs]

GT: Who sold her story to Vanity Fair and put her on 20/20, on ABC, and no one else could talk to her. What a remarkable thing! A woman chops off a penis and has a Hollywood agent. She did. He told her they were going to make a movie.

RB: Only in America.

GT: Only in America. So I did the story. Later on, after Tina would not publish the—

RB: She spiked the story.

GT: She spiked it and I kept it. It’s the same thing I said: You keep it, you dust it off, and think about it, let it germinate. It’s like wine: Sometimes you can be ahead of your time. Like that Orson Welles commercial he used to do on wine: Wine must be left to its own time. Writing is the same thing. You gotta take your time. And sometimes, what didn’t work in 1993 works in 2006. Sometimes you need the perspective, sometimes, if the people you are writing about are in the headlines, that’s when you should not write about them. Because everybody is sick of the subject, and moreover, they think they know more than they do and any kind of deep research you do is wasted.

RB: Did I read correctly that you said something to the effect that either David Remnick is a genius—

GT: You’ve got that right. I said that—

RB: Or that the New Yorker is the best magazine?

GT: No, no. I said that David Remnick’s New Yorker—David Remnick is a genius. I think that the New Yorker he took over from Tina Brown, she didn’t run much of a magazine. But this guy is a soaring figure in American magazine publishing. Every week I read that magazine cover to cover, I read stuff that I am not interested in because—the dance critic, I don’t care, or the “Talk of the Town” pieces—Remnick, it’s astonishing what he does. He also has time to write. He also has a family life—which amazes me, how he organizes himself. I am not saying I know him well because I never worked as a staff person, but I know—one time I had lunch with him, it was before the Christmas—New Year’s period—and he was having lunch with me and I said, “Where are you going for New Year’s?” “I’m going to go to Japan.” “You are? Why are you going there?” “Take my sons.” “You are going to take your sons? Is your wife going?” “No, just them, to spend a few days with them.” I said, “What a guy. Going all the way to Japan with his kids.” Then sometimes I see these long pieces he writes, and where does he find the time? He reads every word that’s in that magazine. I am old enough to have read the New Yorker under four or five editors. [William] Shawn was the longest that I knew.

RB: [Robert] Gottlieb.

GT: Then Gottleib and then Tina Brown—but this guy, it’s at a new level.

RB: I was surprised to see him write from New Orleans after Katrina. But he had sent a number of people, including Jon Lee Anderson.

GT: He’s great, Jon Lee Anderson. I read his stuff, I actually met him once or twice, and I think his writing and reporting—but does he know what he is writing about?

RB: I had met him for his Che [Guevara] biography. He went to Havana and lived there for three, four, or five years with his family, with his young kids. Lived not too far away from an allegedly deactivated Soviet nuclear reactor—

GT: Oh man, I think he is one of the best people.

RB: It’s good that there is a magazine that features quality writing—

GT: There is one quality magazine. And then where do you fall off? People who want to write for magazines are not going to write for Vanity Fair unless you are doing Hollywood—talk about agents—when Lorena Bobbitt gets a Hollywood agent, you can imagine what the real stars have.

RB: [laughs]

GT: They have these jackals over there. They’re in bed with the publishers and editors. There is such a contrivance of business—

RB: So you were speaking with some hopefulness and optimism before about teaching young, aspiring students, and now here we are looking at the real world and—

GT: If you want to write Hollywood, you can make a lot of money. If you want to write pieces for magazines about movie stars, you can get stories in Vanity Fair or GQ or Esquire. Maybe you can do a back-of-the-book thing. As long as you have enough commerce riding on the cover story, meaning the cover has to have a famous person, because people walking past the airport rack or in the streets have to see all the famous faces. But if you write in Vanity Fair, let’s say, about Havana or about Cuba or politics in Afghanistan, you probably could do a long, long piece inside but it’s not going to sell the cover.

RB: Wonderfully, Vanity Fair continues [I think] to use Christopher Hitchens.

GT: He will certainly make waves wherever he goes. And then there are other magazines, I’m sure, that do the same—but if you are doing the big piece, doing the cover story, you are most likely going to have to write about somebody who is very famous and people want to know all about.

RB: Don’t you think it’s odd that a magazine like Esquire that has a long and previously honorable history—

GT: I used to be part of it.

RB:—Had a golden age, and I would point to a story of yours that’s over 30 years old.

GT: [In their 75th anniversary issue] Esquire said it was the best piece that they ever published.

RB: Interesting that they would even hearken back to the golden age. [laughs]

GT: There is a piece that Vanity Fair is publishing—Frank DiGiacomo is the writer, and he used to work for the New York Observer, now under contract for Vanity Fair, and I am going to go with many other people to pose for a picture that is made up of those Esquire writers of that period. Graydon Carter wanted to have this article, I’m sure it will be in the back of the book somewhere and—

RB: Who is still alive? Terry Southern is dead—

GT: Well, no. Norman Mailer, and I don’t know who is in the picture but I can tell you some of the people I know. William F. Buckley. I saw him at Abe Rosenthal’s funeral. He did a lot of pieces. Tom Wolfe is still around. I see Tom a lot. Tom Morgan is still alive. Maybe Dan Wakefield is coming. I am not sure who is coming, only because you raised the issue of Esquire in the ’60s and ’70s. The editor of that period is dead—a man name Harold Hayes. Another editor, who was not at Esquire, he was mostly at New York but worked a little at Esquire—Clay Felker.

RB: He is in California. That was a great moment when Felker and company started New York Magazine. That sounded like magazine heaven.

GT: It was, it was. Although it didn’t seem so at the time. Hayes was a very tough guy, good for the magazine—like Remnick.

RB: Do you still do journalism?

GT: No.

RB: Not at all?

GT: Well, it’s a young man’s game. And also I don’t want to do something that fast. I mean, you could say I have gone to the other extreme. No, I want to take my time.

RB: Would you write something on Floyd Patterson, for instance?

GT: If they’d asked me to do the obituary, I would have done it. I was on the road, actually; I wasn’t in New York. I just heard about on the nightly news. I tell you I haven’t spoken with him for a whole—he had Alzheimer’s and he didn’t know who I was, and so I didn’t keep in touch. But I would have written about him. I mean, I have written about him. That piece I wrote is better than an obituary. It’s the story of a man’s life at a time when he was functioning and conscious and also able to describe the life of the fighter.

RB: You say journalism is a young man’s game—

GT: It’s a first step. What I am trying to say is, it’s a first step.

RB: When you were credited with or identified as the proponent of new [personal] journalism, what did you think about that then?

GT: I was embarrassed.

RB: [laughs]

GT: First I was embarrassed because—I’ll tell you why. Not for one reason but two. Number one, Tom Wolfe was complimenting me. He is a friend and he is generous, Tom Wolfe has a generous spirit. I never heard Tom Wolfe really, really condemn anybody. He might have gotten mad at someone who called him something and replied; he was pretty quick in responding. But basically he is a Southern gentleman, well-born, an intellectual and immensely talented. And he wrote this book called The New Journalism and he puts me in there as the founder, along with others. I was supposed to be the guy he looked up to and what got me embarrassed is the following: His intentions were good but the effects were not. What it did was start this—Tom Wolfe is so popular so whatever he says is new—he discovers for people what is new. And he created this genre. And in this genre comes a lot of odd people who do not do what Wolfe does and I do and David Halberstam does—reporters doing the legwork. You know what it is? Before we start writing, we get to know a lot of stuff and we then put our time in, and we organize it. And then we write it—third stage. A lot of people, these so-called new journalists, especially when it became glamorous, a lot of people were looking to shortcut the process, to do [pieces] full of opinion, full of style, and nothing substantive. Nothing that would hold up. A lot of lies and shortcuts and half-assed nonfiction; it was half fiction and half sloppiness. And I didn’t want to be connected with that, but it was too late. The whole debate of the new journalism—more old people, older than me, saying, “What do you mean, ‘new?’ There’s nothing new about that. George Orwell was doing that.” So I was half defending and half blocking it. I was half defensive and half trying to avoid the issue. Because Tom Wolfe probably made more readers for me. Which he did because he is so popular in the academic world. There are classes on new journalism. People are teaching me [my work]. The only reason people know about “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold” is some college professor and English professor who read Tom Wolfe’s book asked, “Who is this Gay Talese? Oh he wrote blah blah blah.” And they select what they thought was the most readable, or what the students would like the most, or who knows why they did it. I had written better pieces for magazines than “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” but that’s what got selected—maybe because Sinatra was famous and tragic in the movies, and all that stuff.