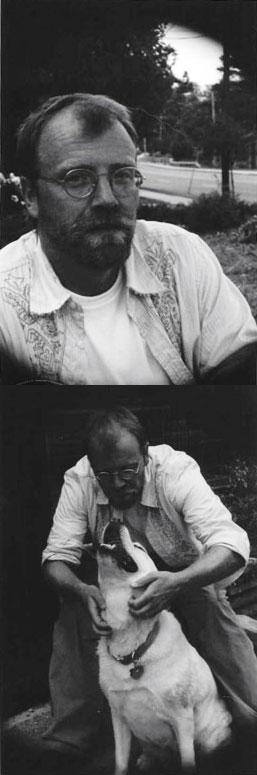

George Saunders was born and raised on the South Side of Chicago, studied geophysical engineering at the Colorado School of Mines, and has a master’s of fine arts from Syracuse University. He has explored for oil in Sumatra, played guitar in a Texas bar band, and worked as a doorman in Beverly Hills, a roofer, and a knuckle-puller in a slaughterhouse. From 1989 to 1996, he was employed as a technical writer and geophysical engineer. Saunders has published two collections of stories, Pastoralia and CivilWarLand in Bad Decline, and a children’s book, The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip, and now his novel (or novella), The Brief and Frightening Reign of Phil. His writing has appeared in the New Yorker, Harper’s, Story, Slate.com, and many other publications. He won the National Magazine Award in 1994 for his story “The 400-pound CEO” and again in 1996 for the story “Bounty.” He lives in Syracuse, N.Y., with his wife and two daughters, and he teaches creative writing at his alma mater. He is currently working on two screenplays, one for CivilWarland and one for his story, “Sea Oak.” His next collection of short stories comes out in spring 2006.

The Brief and Frightening Reign of Phil concerns the tensions between two countries, Inner Horner (a nation so small it can only accommodate one citizen at a time, while the other half dozen must wait their turn) and Outer Horner, which surrounds it. Phil, a power-hungry Outer Hornerite, ramps up international tensions and tramples on the long-standing equilibrium between the two nations. Saunders’s fable of imperialism and exceptionalism is some parts Orwellian caustic vision, some parts shaded Dr. Seuss whimsy, some parts Pynchonian satire but mostly Saunders’s own original, bemused take on the world as he finds it.

As my chat with Saunders below shows, he is a bit of an oddity in the ostensibly predictable world of literary fiction. That “oddity” was cheerfully exhibited in short in an earlier interview with the Missouri (that’s in the Midwest) Review, in which he said of his experience as a student in Syracuse’s creative writing program, “I didn’t know that Doug [Unger] and Toby [Wolff] had had trouble getting me in, though I was aware that many of the other students were from Ivy League English departments… So while the other students knew all about Shelley and Keats, I knew about Alfred Wegener, the father of plate tectonics, who we affectionately used to call ‘Big Al.’ But, you know, fiction is open to whoever comes in the door, as long as you come in energetically, and so I had a feeling there was room for me.”

And in longer form below.

Robert Birnbaum: Sitting here in front of Freedom of Espresso in Fayetteville, not Arkansas, New York. We were talking about Stuart Dybek whom I spoke with recently and he said something like, “I know many of these people that you have spoken with—I wonder if the writerly, literary community is connected just in the ordinary ways that professions are.”

George Saunders: Yeah.

RB: “Or if there is something different going on?”

GS: From my experience, it’s not real social. You don’t spend a lot of time together or hang out together. Like Stuart, I probably have seen him maybe four times in my life. But I feel like we have known each other forever. And same with Tobias Wolff, who was my teacher here [at Syracuse]. Maybe you see him once a year, but [pauses] but things happen quickly when you meet. I had a really great day with Jonathan Franzen once. We just walked around the city [New York] for about three hours, and something kind of cut to the chase.

RB: Stuart observed that the great thing about making friends within the world of literature is that there is a direct connection and that one doesn’t have to spend a lot of time going through the protocols of becoming friends. And the contacts you make are ones with interests that seem to blossom and grow.

GS: Because your work precedes you a little bit, the best part of yourself goes forward and the best part of them, and it really is nice.

RB: Some people might not make that claim, that the writing is their best part. [laughs]

GS: I hope, I hope. The rest is pretty crap. You get that refined part of yourself that you have sweated over in that kind of secret way and then if somebody can get through that and still wants to meet you, then there is something.

RB: Do you see your writing as your public face?

GS: Um, I think maybe a more private face.

RB: The private face that you publicize.

GS: If you are lucky.

RB: [laughs]

GS: It’s kind of like—for me, I am a real obsessive rewriter so that there is just an efficiency that gets put in there that feels like a purification. If I had to write you a letter for two minutes it would be all over the place and there would be a lot of falseness, intentional or unintentional falsehood, and a lot of drift and a lot of stuff where you are self promoting in a kind of disgusting way. You know you are trying to, “I’m likable” or “I’m…” But with fiction somehow, the rewriting and the revision, it gets rid of that character flaw stuff. For me, I am little bit, as a former Chicago Catholic, I always want to be liked. That’s one of my big flaws. In fiction that’s a little bit if not cleaned out, at least purified. It’s still there a bit; it’s, maybe it’s its best face.

RB: You’re not thinking about being liked when you are writing?

GS: I am but [pauses] but I am going to be liked for the right reasons. Instead of trying to schmaltz someone into liking me, I am going to put myself out there as honestly as I can and that will be likable, maybe. Something like that.

RB: Let me step back and ask why the Chicago Catholic characteristic of wanting to be liked is a flaw?

GS: All characteristics have two faces. There is the kind of raw face, which is often—at least for me—often an avoidance kind of thing. And then there is the pure face, which is, you take that tendency and you just clean it and use it in the best way. So to be liked is certainly cool but it’s a slight turn of the dial. Or let’s say you are aggressive. That can be really obnoxious or it can be present. In writing something about working through the technical dynamics of it and having done so for 20 years, you start cleaning things out. I don’t know how else to say it. Well, you’re putting your best foot forward, I guess, in a certain way.

RB: Is there a clear relationship between the writing and your personality as you move around in the world? You have been writing 20 years and you have been doing it in a certain way to refine certain things that you want to communicate, so are you a different person because of your writing?

GS: Yes, yes. What happens is that the things that get brought forth when you are working in a story then become things that you can drape your personality around in a certain way. But you knew that this was a tendency in yourself—having written it, then, it’s concrete and you can jump to that next level.

RB: It’s like saying, “I didn’t know I thought that.”

GS: Exactly and when I was younger I thought it was the other way around. I thought you had to figure out who you were and then type it.

RB: [laughs]

GS: Now it feels much more like you don’t know who you are until you have worked—and it’s not even—it happens for me over a course of months. You finish something and then you go—and even then it’s not the intellectual part, it’s the visceral part. You have made this thing. Like I just had this “CommComm” story in the New Yorker; through the long process of working on that, I figured out something about how I want to proceed with my life from here. Just a small, I couldn’t express it, a small thing. I kind of knew it before but having written the story there is no looking back. So the process of having the subconscious purify that—

RB: I don’t think I have heard anyone say that—that is, to talk about the intimacy of their own thinking process affecting their life decisions—they always seem so separate.

GS: It is discrete but then I noticed—well, for me it has to do—it never happened when I was young and I wrote a story quick. But as I get older and I am taking longer and longer, I have a feeling that the subconscious mind is sort of forming itself behind the story that you are working on in some way. And if you go slow enough it overtakes the story at the end and that’s that epiphanic thing that people talk about. And then for me that’s nice that happens—

I always think if you write a story about a clown being decapitated, it doesn’t mean that you have anything against clowns.

RB: If you go slow enough.

GS: For me that’s how it is. Because then when you go slow enough it’s a feeling. When you are going fast, your conscious mind is driving the car, “This is a story about patriarchy.” Good. But when you go slowly, you don’t know what it is. And suddenly your concept of the story has to get junked at a certain point and your anxieties about the story’s inadequacy are suddenly what the whole story is about and the whole thing changes. It doesn’t happen that often, but when it does it’s really good and cool.

RB: So how did you get into this? You didn’t intend to be a writer, did you?

GS: No, I was an engineering student at the School of Mines in Colorado. I have always had an affinity for written language but I didn’t quite—

RB: Having anything to do with Catholic school?

GS: Just neurologically and oh yeah—I wrote about this—I had a nun give me Johnny Tremain when I was in third grade and that really turned me on. I was kind of in love with her.

RB: I liked that book, too.

GS: Yeah, it was stylistically dense. But she kind of gave it to me like an insider gift, like, “I don’t know, not too many of these schmucks could manage this, but you can.”

RB: [laughs]

GS: So just neurologically, people that end up—

RB: You didn’t act on it because your family wanted you to have a real career?

GS: They were always very accepting. It was more a macho thing.

RB: To become an engineer?

GS: I had read Ayn Rand—

RB: [laughs]

GS:—at a vulnerable moment and I didn’t want to be one of those life-sucking parasitic artists. So then I went to engineering school and some good friends of mine that were teachers at my high school got me in—my grades weren’t so great. And then it became this mission to graduate from there and I did and went over to work in Asia in the oil fields and all the time I was reading. I had read only Thomas Wolfe and Faulkner and de Maupassant. So it was a really gradual thing. And then after I had been in Asia for a few years, I decided I really wanted to do it [write]. That’s why Dybek is so important, because I had never read a contemporary writer before him.

RB: Really?

GS: Or read it and loved it. He had this story, “Hot Ice,” which was set in my dad’s old neighborhood, and [it was] something about that experience of seeing an actual place that you knew in fiction and then you could understand the transformed worth. With Hemingway, you just think people talked differently in the ’30s and were nobler, which is bullshit. They weren’t. That was where I—

RB: Yeah, that was a fun part of reading Dybek, although I’m from the North Side [of Chicago], which is a world apart. He quoted one of those malapropisms that the first Mayor Daley was noted for, “We have risen to new platitudes of success.” Anyway, the Syracuse website listed your various jobs. Did you choose that?

GS: That was my choice a long time ago when my first book came out. They said, “Give us something to work with.” They are all true, so I listed them. But they sort of linger—stick around. With that first book, there is that pressure to have some kind of hook or something. But that was a long time ago.

RB: I must tell you, when I read your stories in the past, I liked them but I found it difficult to read through the books, short as they are, in a sitting or two. I had to parcel them out. There is something that happens, for me, that I feel like I have been made dizzy or disoriented or something.

GS: I know what you mean, and I wish that I could say, “Please read one or two a day.” There is something about this style that goes flat. I am putting this new story collection together and if I try to read the whole thing at once, there is something about it. Because they are dense? And there is not a lot of physical description. And after a while you can’t get any purchase on them. So, if I could put a disclaimer on them, it would be, “Please read one or two a day and stop.” It’s almost like they are written at a certain volume and if you read them too fast, you can’t hear the nuances, I think.

RB: Yes. Is this something that others have said?

GS: My editor said it and I never really noticed it. The way I do them, I write a story every four or five months so when I am in that one it always feels—you can see the contours. But then when you put it in a book—they are all so fast, it’s a little bit like ice. So you’re absolutely right about that. My hope is that someone will just get two stories in and go, “Sheesh,” take a break, and come back later.

RB: You wrote something for Amazon a few years ago disclaiming that you were a dystopian futurist. Was that a common judgment about you? Or one person said it and you decided to preempt a trend?

GS: I don’t remember.

RB: Or did anyone say it?

GS: Yeah, I said, “Don’t even think about saying this.” No, there were a lot—around the time of the first book, there were lots of questions like, [in a fey voice] “Do you think it’s gonna happen like this?” And that was never even on my mind, that it was predictive of anything. So I think I wrote that for that reason and because people would say, “It’s such a dark vision.” To me, it isn’t. I mean, it’s kind of like saying, “Let’s assume for a minute that we are going to take certain human qualities out of the equation—we’re going exaggerate the whole mix a little bit and then have a whole book in that flavor.” I don’t think it means that those things don’t exist—those missing flavors, but it’s a way of saying—if you could look around here now and take all of the greens out and replace it with orange, you would suddenly be aware of green. So, it was something like that. I am a very happy person.

RB: Let’s make sure to emphasize: George is a very happy person.

GS: Very happy.

RB: I don’t read reviews much—so has that continued? I do sense that you are regarded with great admiration by writers and such that I am acquainted with—

GS: The second book had less of a theme-park thing in it and there was maybe more of a glint of hope, not that I thought it was missing from the first one. I’m not sure.

RB: It’s a little baffling to me. I think your writing is hilarious.

GS: Dark and funny seems to be the—to me dark—being from Chicago, “dark” is not saying, “Shit can happen.” “Dark” is like TV where only shit happens with no sense of humor and no acknowledgment of any brightness. That’s real dark. So I always think if you write a story about a clown being decapitated, it doesn’t mean that you have anything against clowns. You can’t.

RB: Or decapitation? What was the starting point for The Brief and Terrible Reign of Phil? Did I get the title right? I can’t remember.

GS: I can’t either. [The title is The Brief and Frightening Reign of Phil.—ed.] I was working with Lane Smith on that Gappers book and he said, “You should try to write a—

RB:—try to write an adult book.”

GS: Yeah, “Try to write a book in which all the characters are abstract shapes.” So I said OK. So I started messing around with that. Trying to think of a world that would take place on this sheet of paper, then I started to get into this geography of what countries are shaped like. A sentence fell out about a country that was so small that only one citizen at a time could live in it. So my approach is usually just take something that is coming off the page a little bit and then isolate it like a seed crystal and just sit there with it and mess around with it and see what grows on either side of it and try as much as possible to keep a central idea out of it.

RB: You didn’t know what the story was?

GS: No, not at all. It just started with that idea and then that led to the idea, where do the other people go?, and then suddenly there is this outer country surrounding it and then the genocide thing just kind of—I don’t know, it just worked its way out.

RB: Would you read something for me?

GS: Sure.

RB: That will allow me to serendipitously put this in our chat—where it says, “‘My people,’ he shouted in a stentorian voice.”

GS: Yeah, yeah absolutely. I won’t shout it in a stentorian voice—we could make a scene in Fayetteville.

RB: All of a sudden traffic stops and a crowd collects. [laughs]

GS: This is where Phil is taking over, and he makes a speech:

“‘My people,’ he shouted in a stentorian voice. ‘I shall speak now of us. Who are we? We are an articulate people. A people of few words. We feel deeply yet refrain from embarrassing displays of emotion. Though firm we are not too firm. Though we love fun we never have fun in a silly way that makes us appear ridiculous unless that is our intent. Our national coloration though varied is consistent. Everything about us is as it should be. For example, we can be excessive when excess is called for and yet even in our excess we show good taste. Although never is our taste so super refined so as to seem precious. Even the extent to which we are moderate is moderate except when we have decided to be immoderately moderate or even shockingly flamboyant at which time our flamboyance is truly breathtaking in a really startling way. When we decide to make mistakes our mistakes are as big and grand and as irrevocable as any nation of colossal errors. And when we decide to deny our mistakes we sound just as if we are telling the truth. And when we decide to admit our errors we do so in a way that is truly moving in its extreme frankness. Am I making sense? Am I saying this well?’”

RB: That stunned me.

GS: For me, this book was a side project for six years that I would come back to and the fun of it was to try to figure out the voice for all the different little creatures. When you make a being out of scratch, then it’s interesting the way that the psychological things come in. It was fun.

RB: Six years?

GS: On and off.

RB: Thinking and then writing a little bit?

GS: On this one, in the last six years I had this disturbing pattern of getting about three-quarters of the way into a story and then locking up on it. Like in this case I had this up to about 300 pages at one point. Just different vignettes. But at around 50 the momentum went out of it. And so it was a lot of trial and error to see what’s the scale of the book, and it’s a silly idea, how far can you take it before it outlives itself? It’s that thing we talked about earlier when the subconscious kind of—you have to keep it behind you. When I get excited, I tend to crank out a bunch of stuff and then the whole thing kind of stalls. It was mostly just waiting a long time to see; maybe to disengage from the idea that this was a six-volume set. [both laugh] No, it’s not it’s a 70- or 130-page—

RB:—you can join [author of multi-volumed history of the world British historian Theodore Arnold Joseph] Toynbee and William Vollman.

GS: Right, except Vollman would actually do it. I can’t do it. I don’t have that ability. The thing is, as I was doing it, I started off with Bosnia and Rwanda in the back of my mind. And then six years are passing so 9/11 happened, so for me it became not like Animal Farm in that it’s a point-to-point correspondence with something that actually happened but rather playing around with this idea of us versus them and as soon as we recognize us and them we try to kill them, and the process, the best way is to make sure we don’t think of them as human anymore and then we can do what we want, that kept coming up again and again.

To see Toby working, with a family that he dearly loved, working industriously, beyond industriously, beautifully every day, turning out these masterpieces, and he was a nice person. A loving and loved person. That was a big thing to say that was OK. We are working at a higher level than personal quirkiness—we are talking about the work itself.

RB: Any thoughts about how this book will be received?

GS: No, I don’t know. We’ve gotten three reviews—a Kirkus and a PW [Publishers Weekly] and then one from Florida.

RB: Does the word “allegory” come up?

GS: One of the reviews reviewed it as a kids’ book, which I didn’t expect. And then one of them seemed to think I was writing an allegory of Iraq and then pointed out the fact that it wasn’t accurate—which I know.

RB: Always a good trick, incorrectly claiming it’s about something and then criticize it for being wrong.

GS: I can kind of understand it because there are definite overtones that bring that up.

RB: Well, it is an exhibition of an imperialist, exceptionalist take on government and international relations.

GS: Right, right.

RB: Well, I’m going to read this to my son, who is seven, and I’ll let you know.

GS: I’d be interested in knowing. Originally I wanted it to be a kids’ book. That was the plan but then you get to a point you’re on the verge of writing a speech like the one I just read and you think, “That doesn’t really go in a kids’ book,” but there it is, it’s hanging there, so you do it anyway and wait and see.

RB: I try not to underestimate kids.

GS: It’s true.

RB: I don’t think my son has to understand all the words to get something out of this, especially when I start laughing reading this.

GS: Exactly, and it’s contextual, too. He’ll pick it up. I just read the Rootabaga Stories by Carl Sandburg. It’s fantastic. It’s a series of two or three crazy books. Really crazy, kind of like myths about the Midwest, a Midwest-on-acid kind of thing. They are really crazy and funny and beautifully written. And they are not for kids, but kids like them. Or like the Just So Stories of Killing. My feeling has always been since if you have a very limited talent, which I do, you take what’s there. I spent a lot of time when I was in my 40s picking and choosing, “Oh, that’s not Hemingwayesque enough. I don’t want to do that. I want to be this kind of writer.” And I thought, “You don’t have the talent for that. You better just take it.” If something presents itself to you, you better just grab it and trust it, if you pay enough attention to it, it will be something in the end. So I don’t know, really, what the book is.

RB: You’ve been teaching a while.

GS: Seven years.

RB: That’s not so long, a fair amount of time. When you say about yourself you have limited talent and—I was going to use the word “presume”—and then you take upon yourself the responsibility of teaching—how does your assessment of your own talent affect your teaching?

GS: Basically—[pause] When I say “limited,” I mean it’s not 360 degrees. It’s a narrow kind of thing and my experience is, my students are brilliant. We get 200 applications a year and we pick six. There is something that happens when they accept that about themselves, that they can’t do everything well. That even though they could probably do a kick-ass imitation of Faulkner or Cormac McCarthy or whoever, they could an 89 percent imitation but if they want to get to 98 percent they have to find out that little range of their own talent that locks in with their psychology and then pushes them ahead a little bit. I mean, yeah, that there’s some magic zone when your psychology and your spirituality and your whatever and your experiences line up and you can do something that’s inexplicably good, and if you drop off that you can be pretty decent, but getting into that little wedge of unlikely accomplishment is what this grad student experience is about. That’s very psychological and nurturing and odd, the way that that works. Everyone there can write anything beautifully. That’s not even a question. The top 20 people could do that—we pick six of those. So then what you are trying to do is nudge them out on the little window ledge.

RB: Are prospective students interviewed?

GS: We don’t do that. We just do that off the work. They send us stories and we pick off of that. Which actually is kind of cool.

RB: This notion that something is built into the process of unlocking their talent is seemingly more than is expected of teachers and more than what they normally do, right?

GS: On a graduate level—you hear stories and that kind of intimacy is expected at that level. I think.

RB: Really?

GS: I think so. Just in a sense that you are seeing somebody three times a week for three years. And they are grownups and you are grown up.

RB: Three-year program?

GS: Yeah. The thing about Syracuse that is extraordinary is that we have 100 percent funding for everybody. So if you get in, there’s free tuition and you get about $13,000 a year for doing a range of things. Nobody has to go $80,000 in debt. So we can get anybody, they don’t have to be wealthy to come here.

RB: And not worrying about ending their stint deeply in debt.

GS: Just the usual problem of no job and no prospects. [both laugh]

RB: Was that your experience when you came here?

GS: Yeah, I studied with Tobias Wolff and Douglas Unger and at that time it was only a two-year program and there was lot of teaching, what I consider teaching beneath the teaching. For example, for me, I had a very Kerouackian view of writing: you had to be a fucking nut.

RB: You had to write on rolls of toilet paper?

GS: [chuckles] You had to be crazy. Drunk or something. Messed up. And I didn’t really feel like I was that messed up in an overt way. I was worried. To see Toby working, with a family that he dearly loved, working industriously, beyond industriously, beautifully every day, turning out these masterpieces, and he was a nice person. A loving and loved person. That was a big thing to say that was OK. We are working at a higher level than personal quirkiness—we are talking about the work itself. What you do in your life is not—doesn’t matter,

RB: I was reading Peter Kramer’s Against Depression, and he is very much against the notion that an illness is viewed as integral to creativity. Remove the burden of depression; can artists still be creative?

GS: If you cure them, can they still be creative?

RB: Right. If Van Gogh had been happy person, would he have painted or painted with his [same] genius? Kramer argues this is bullshit.

GS: I think Van Gogh would have painted.

RB: I bring this up because we have these stereotypes of artists and their personas. Wallace Stevens or Charles Ives or David Ignatow leading outwardly lived normal lives is not the image we have.

GS: It makes it scarier when you don’t have the crutch of flamboyance. We don’t care what kind of person they are. What do the words say? That’s scary in a way. It’s easier to wear the cravat and—

RB: And be a poseur.

GS: This goes back to what we said earlier. There is a story that I tell too much but I love it. Tolstoy and Gorky are in Moscow and Tolstoy sees these Hussars coming towards them, Russian Green Berets, and he says, “Ah, that’s everything that’s wrong with Russia. The preening and the self, the narcissism and the aggression—it’s going to be the end of Russia.” And Gorky is really impressed and convinced. So they walk by, and Tolstoy turns on his heel and says, “On the other hand, what magnificent specimens.” And he goes on and on in the other direction. That’s the thing about art that’s so powerful. A person’s depressed. OK. Good thing or bad thing? Both, and if a person can describe a “depressed” state, through both the lens of what it feels like, how it feels when you are clear of it, a holographic three-dimensional—

RB: Kramer doesn’t want to lose sight that depression is absolutely and finally an illness, nothing is gained. Being able to describe it doesn’t mitigate.

GS: If your aim is therapeutic, that might be true. In the same way that we are at a particular intersection here with particular features, if a person is depressed and he is a character in your book, he has a certain thing and—this is another flaw that I find in my writing so far—it seems satire comes pretty easy for me. I can get into a given situation and make fun of it pretty readily and with a certain love. But I think fiction is supposed to praise as well. Be able to—

RB: Uplift?

GS: I don’t know about uplift but at least represent both. I am finding that I have technical limits. I was in Dubai recently. I saw so many beautiful things. Just beautiful things. And as I am trying to write about them, they are startlingly maudlin. Not in reality but in my writing they are maudlin. So that’s something I try to set for myself as I get into my 50s, is to try to figure out—I was in New York last Christmas and I walked past one of those store windows, beautiful, and I looked at it and involuntarily got that youth-at-Christmas felling, like “Ahh!” Everything is possible. And I thought, “Can I write that? No, I only wish I could.” I don’t quite know how to do that with out cutting the legs out from under it. So that’s a challenge for me.

RB: Vocabulary? Pace? Empathy?

GS: It’s courage. If I wrote that scene just as it was it would come off a little saccharine and the great writers, say, so be it and they walk away and they go on to the next thing and they leave that hanging in the air and maybe later it’s brought up again but with me I don’t quite have the confidence, so as soon as I see myself being a little too earnest I have immediately to cut the legs from under it. So that’s an interesting thing to try to work with as I get older.

[pause while flipping tape over]

RB: We were talking about some of your many flaws—how many is that now?

GS: Not enough. Mea culpa, mea culpa.

RB: Would you say that your career arc [arches eyebrows]—I’m going to write in I arched my eyebrows—

GS:—stood up and vomited—[laughs]

RB:—your so-called career arc has been accidental?

GS: Yeah, yeah.

RB: So here you are, ensconced in a prestigious university in a highly regarded writing program, well received by your peers and the literary community, recognized by Entertainment Weekly and other paragons of high journalism—

GS: Uh huh, uh huh.

RB:—at mid life, so we say. So do you think much about what you want to do in the next five years and beyond?

GS: I would just really like to [pauses] keep trying to write the one thing that is good. That really—that I would stand behind. It’s interesting because it doesn’t seem to me—I used to think, “When I get the first book out, then I am going to be happy. I am not going to be neurotic anymore.”

RB: [laughs]

GS: “I am going to be joyful all the time.” Then actually it got worse. So I’m trying to correct my approach and say, “Most of your attention is on whatever you are doing at the moment, that’s fun.” With the humble goal of saying, “This probably sucks in some way. Forgive me, let me try again.” And with that in mind—

RB: Why does that feeling or thought accompany your work? This self-consciousness about its quality?

GS: It should. [pause] I’ll tell you what, for me when I am working in fiction, there is something that happens—you come up with an approach, and even as you are doing it you see the limitations of it. So somehow, accepting the limitations is key to getting the most out of it that you can.

RB: That’s not a statement about its quality—if my car only can go 75 miles an hour, that’s what I know it can do—I don’t say it’s good car or a bad car. I say it can only go 75 miles an hour.

GS: For me, the self-effacement has something to do with, uh, I don’t know—it’s a form of hope. All I am saying is I did my best, while I was working in this I really enjoyed it but I promise it’s going to get better. Maybe that’s a Catholic thing too? The inner nun—

RB: [laughs]

GS: To me it somehow makes it less stressful and more enjoyable to say, “Someday I am going to get there.”

RB: Probably lots of people have said, “If I ever made the perfect photo or painted the best picture I could or wrote the best story or whatever one does—I would stop there. Never do another.” Is that what you feel?

GS: It’s the opposite. I think I would say—only because it would be so sad to quit. I’d love to keep going. For some reason I’m thinking of a python eating a mouse, you go, “There’s a mouse! I’m going to eat it. Oh, I ate it! Where’s the next mouse?” Just kind of keep going like that. And the creative enterprise becomes a source of pleasure that doesn’t have to be the end, the mother of all pleasures. It’s just one more thing that you do.

If you make a scale and on one side you put 7,000 people who are watching a sitcom or a reality show and on the other side you put one person who is reading Alice Munro, I think there is more energy in the one person.

RB: At this point in your life, would you do something else?

GS: I’d rather not. I really love it.

RB: Are there other things you might even entertain?

GS: No. I’ve been writing movie scripts—that’s sort of related.

RB: Script or scripts?

GS: Scripts, two.

RB: I know about CivilWarland. What’s the second one?

GS: For the story called “Sea Oak.” And then one for CivilWarLand.

RB: How’s that going?

GS: It’s done, and they’re going to start getting the money together soon.

RB: [laughs]

GS: I’m sure that will be no big deal, [both laugh] he says facetiously. Apparently it actually costs money. Strange.

RB: Have you gotten your money for the script?

GS: Oh yeah. I am working with Ben Stiller and he’s great. He’s been very generous. So I don’t know.

RB: Given your narrow talents, this would be an area where you could at least get some stories out it.

GS: Oh yeah, anthropology. For me to be outside the process for 40ish years and then be let in is anthropologically interesting. There’s this huge thing that probably supplies 80 to 90 percent of the stories that people actually process. Which is not one person, one story. My experience has so far been really great because it’s just been me and Ben and his producer.

RB: No meetings in Hollywood?

GS: Yeah sometimes, but just with him.

RB: No boardrooms or corporate tap dancing?

GS: No it’s been very pure. And that’s because I am hiding behind him [Ben Stiller], basically. He’s running interference. If I could just keep working on stories for another X number of years, that would be very satisfying. Sometimes I think a novel would be fun, but I have feeling it will tell me when it’s time. I can’t do it as of now.

RB: This has been an expansive year—the Phil book, the Dubai trip writing for another journalistic paragon, GQ, and doing the movie. Any poetry?

GS: No—yeah, actually I did.

RB: [laughs]

GS: The New Yorker has this fashion issue coming out and they asked if I would do some imitations of Edward Gorey. It turns out in my hands he sounds just like Dr. Seuss. And I just finished up this book of stories that’s coming out next year. The last book came out in 2000, so it’s been a long time. It’s nice.

RB: You did those pieces for Slate.com on Iraq. What was the response to them?

GS: I did one called “Exit Strategy” and one called “Manifesto” and some political things for the New Yorker. It was good but frustrating [pause] my experience has been, you publish a political piece in the New Yorker and basically you are going to hear from the people who agree with you. And Slate, which is a different audience, I had a couple people saying, “You idiot, that’s not viable.”

RB: [uproarious laughter]

GS: You know that’s a misunderstanding. I felt basically, like I suppose everybody, ineffective—you say what you think and the wheel continues to roll. It made me feel better. After 9/11, when there was that strange period when everyone was being accused of disloyalty and all that, there was one week when Gore and Tom Daschle simultaneously said, “Enough is enough,” and it was really, even as member of the choir, it was satisfying to hear that. So that’s a reason to write those kinds of pieces.

RB: I guess Howard Dean is loading up the testosterone quotient for the Dems, but the condition and the role of political opposition in this country are astounding to me, as astounding as what has been accepted as the objective reality and legitimate information.

GS: It’s got to go a different way because the level of—if it’s a word, rabidity, its too high—

RB: Toxicity.

GS: Yeah, yeah, it’s not—

RB: I was watching the Lehrer Hour or whatever [The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer—eds.] and the issue was PBS funding and on one side was a conservative attack—I knew this because no matter what was brought up he would revert to his main talking point about Bill Moyers and his dangerous liberalism and on the other side was a PBS station manager from Denver who pointed out that Moyers represented a miniscule iota of the programming and also pointed out that no one, especially liberals, objected to the many years of Bill Buckley’s Firing Line.

GS: That’s scary. They have talking points but it’s true on both sides. If you want to be “effective,” you have three talking points and no matter what is said, you just repeat them, which makes for a very Kafkaesque thing. The trick is to recognize that in every rabid fill-in-the-blank Republican, say, there is a little Democrat and the reason he is so loud is because he’s afraid of the Democrat and the inverse is true, and that’s why I think fiction can help. If you see someone sympathetically portrayed from the inside it’s a little less scary. But these are odd times—very odd times.

RB: I share your view that fiction might mitigate some of this stuff. Want to take a shot at the status of fiction in the culture today?

GS: Ah ha, the other thing is that—you are absolutely right also, that’s a kind of demographic thinking that we all engage in and really for me—and maybe this is just a survival mechanism—but I try to think of the one reader and the transformative effects. Even if that reader is already convinced and it [just] assures her. But I know what you mean.

RB: I’m with you. I don’t buy this declinist, Chicken Little, sky-is-falling view. There is much more reason to hope and I can’t substantiate it but to say that the mass culture is just mega-decibels noisier and so it drowns out everything. Literature is not going anyplace. Gail Caldwell wrote a real swell affirmative piece in the Boston Globe recently starting off with praise of Alice Munro and disdaining the decline or retreat of readers.

GS: If you make a scale and on one side you put 7,000 people who are watching a sitcom or a reality show and [on the other side] you put one person who is reading Alice Munro, I think there is more energy in the one person. And when you talk about the way things actually change and the way life actually ebbs, that is very ephemeral, the 7,000 people watching Honey, I Killed the Cat.

RB: They have the weight of a goose-down pillow.

GS: Right, but they could be transformed. I don’t think you ever want to saddle literature with purposefulness. It can be, but if it tries to be it gets a little crazed.

RB: I agree. There an ineffable quality, that maybe a religious thing.

GS: It’s a useless thing that gives pleasure. And after that I can say, “And also,” but you have to stop there if you really want to be truthful. It’s like sex. It’s a useless thing that gives pleasure.

RB: Now wait a minute. I think it’s one of the purely life-affirming things.

GS: By life-affirming, that does mean—

RB: I was just thinking as I was driving through New York state, I don’t know what I was thinking and it wasn’t erotic—I was thinking about sex and it occurred to me that’s what happens when someone keeps gasping, “Yes, Yes, YES.”

GS: Right, right, BRAVO! It’s true, but like anything, that’s life affirming, a good movie or good book or good sex or whatever, it takes a certain amount of wisdom to stop and not have to comment on it—”Honey, did you like the part where I…” With writing because it’s words and it’s politically tinged like mine, there is that tendency to say, “Am I helping?” But I have a feeling in the same way that when you have great sex, you don’t say, “Am I helping?” I mean you are, you know you are, but—

RB: It exists in its own moment and the secondary stuff is taking up time or self-congratulation?

GS: Insecurity. You’re pretty sure you had a powerful experience and now you want to corroborate it.

RB: So we have charted out your career or career arc, so what else is there? Have any unusual hobbies?

GS: No, I play the guitar, but that’s about it.

RB: Do you write songs?

GS: I used to but I don’t [now]. Somehow they don’t really come to much. They are in that 80 percent or whatever it is—they’re all right, that’s a song.

RB: What kind of music do you like?

GS: I like Elliott Smith and folk rock and everything. I long ago recognized my limitations, so it’s just a hobby. I do it in between writing at home.

RB: Do you listen to music when you write?

GS: No, I feel like if I am doing that I am giving a false lift to the words. Better they should do the work on their own.

RB: You have two children.

GS: Our kids are in high school now and almost in college, so it’s kind of an interesting transition.

RB: Do you worry about them?

GS: Ah, yeah, yeah. But less—they are really excellent people, and so I am excited.

RB: Are you a better parent than your parents?

GS: No, my parents were pretty good. I hope I am as good. How about you?

RB: My son was born when I was 50 years old. It’s a cliché, but he changed my life.

GS: They do. When we had our first daughter I found that—before that, I was 28 and I couldn’t quite figure out morality. I understood you weren’t supposed to do A, B, C, and D, and I generally didn’t. I was pretty self-regulated but it didn’t make sense to me viscerally. I thought, “Why wouldn’t you be wildly promiscuous? Why wouldn’t you be messed up all of the time?” And then after we had her, everything clicked in. “OK, so if I love her that much, everyone else could potentially be or is loved that much,” and everything just popped in there. It’s interesting to get to this point with them—suddenly, you see, not only are they going to go off on their own but they have to—you can’t linger in that. And so you kind of get your old life back a little. But you are not entirely sure you want it. But then, knock on wood, you are still pretty healthy, so it’s exciting. That’s what this Dubai trip was partly about. Just to see what are some different modes of living once they go off.

RB: I am already keenly aware of having maybe 10 more years with my son before he goes off to wherever—

GS: Right, I remember very clearly when they were little, saying to myself, “You better pay attention to them and don’t screw around and really be there.” And I think I was, but at the end of it you still go, “Damn it. I know I missed it.” We were watching old home videos yesterday and, God, it just kills you!” But—[drifts off, leaving thought unfinished]

RB: So your short stories come out in 2006?

GS: May of 2006.

RB: I assume we’ll meet and speak again.

GS: I hope so.

RB: Especially since we haven’t exhausted the world as we have found it. Let’s do this again.

GS: Absolutely, I’d love to. All right, man.

RB: Good work, Rosie.