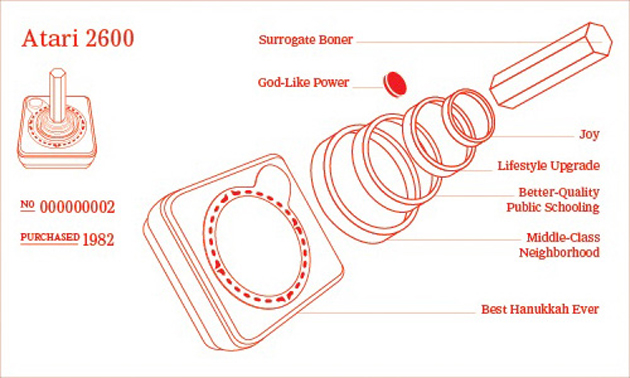

Radio Shack TV Scoreboard (1979)

In 1979, my father brought home a beige-colored box made of industrial plastic. There were a few metal toggles and dials on the face, and a tangle of black electrical cords hanging from it, attached to a pair of smaller plastic boxes outfitted with small, sliding dimmer switches. It looked like something hospitals use to test blood glucose levels, or jump-start a patient’s heart. But, instead of squirting conductive jelly on its two electric paddles, my father hooked the device up to our 13-inch black-and-white television set, gathered up his children, and said, “Here is your new toy.”

The Radio Shack TV Scoreboard was my first video game system. It was a late entry into the Pong-dedicated home console market , and it was a really crummy, gimped system, too—basically featureless, with the exception of a large dial used to select one of its nearly identical, built-in games (Tennis, Squash, Football, and a fourth simply called Practice). Our TV Scoreboard didn’t even ship with a requisite light gun for TV skeet shooting, which meant it managed to shimmy beneath the already perilously low bar set for home video game standards in 1979. My brother, sister, and I made do, of course, but the Radio Shack TV Scoreboard never commanded our full attention, possibly because we weren’t big fans of Squash. Besides, our gaming system, though novel to us, was already hopelessly behind the curve. While I was tweaking my slider and trying to mix things up in my parents’ bedroom by adjusting my paddle length and ball speed, the really cool (i.e., wealthy) kids were spending several hours a day in their tastefully paneled basement rec rooms, furiously throttling their joysticks.

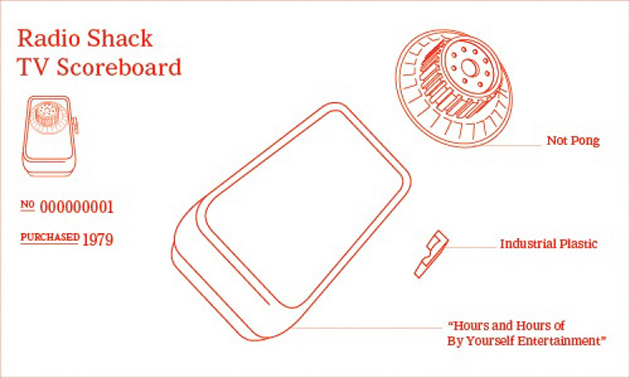

Atari 2600 (1982)

If we were late adopters for Pong, we were practically living off the grid when it came to Atari. In 1981, my family moved from a blighted urban neighborhood to a more solid middle-class area of Albany, called Pine Hills. Even though the move created a financial strain and required that my mother return to the workforce, my parents considered this lifestyle upgrade necessary to the pursuit of better-quality public schooling, and to reduce our risk of Doberman attacks.

It also meant our family was entering a new, higher social class, at the sub-basement level. I would no longer be the envy of the assisted-income kids on my block, with my fancy Pong system from the future, and my complete set of chromosomes. Now, in the comparatively tony comfort of Pine Hills (i.e., smaller, less vicious dogs), every kid had a fresh pair of Nikes, a Lee stonewashed denim jacket, a healthy stipend for souvenirs on field trips, and an Atari video game system. My off-brand clothing, purchased at Denby’s—a local department store best described as a slightly more affordable and slightly more provincial JC Penney—meant my social status was tenuous at best. Inviting friends over to my house after school for a couple of games of Practice on the Radio Shack TV Defibrillator was the fast-track to leprous seclusion. I had to have an Atari, or risk spending the remainder of pre-adolescence exiled in my darkened bedroom, trapped beneath a Collyer Brothers-esque pile of Yes & Know Invisible Ink Quiz Books. (Each book’s cover cruelly promised “HOURS and HOURS of ‘BY YOURSELF ENJOYMENT’® for ages 9-99.”)

That’s why, beginning in the spring of 1981, I enlisted my siblings to join me in an aggressive campaign of whining and pleading that didn’t end until Hanukkah of 1982, when my father finally relented and brought home an Atari he found on sale at some depressing wholesale appliance liquidator in one of the Albany suburbs.

It was my father’s Hanukkah tradition to craft elaborate illusions and misdirection in order to maintain some element of surprise in our gifts. He would switch packaging, camouflaging our most coveted toys with boxes for joyless household appliances—sometimes even adding scraps of metal to approximate the soul-deadening clunk of hardware when the package was shaken. “Oh, jeez! I must have wrapped the wrong gift. That was supposed to be for your mother,” my father would say, feigning shock and embarrassment. “Well, you might as well open it to save your mom the trouble.” Then, while my father continued to “aw shucks” his idiotic mix-up, my sister would open the package and find a Holly Hobbie doll crammed inside a Conair Pistol Power Hair Dryer box like a murdered prostitute. My father relished the explosions of relief and joy following these weary moments of dread, and he was masterful at creating them. But we broke his playful spirit so thoroughly during the ’81-’82 Atari acquisition campaign that he just handed over the console, unwrapped, a full week in advance of Hanukkah. As we pounced on the plastic bag from Green’s Appliance Direct, my father warned us, “You’re not getting the game cartridge until the seventh night of Hanukkah. If you’re upset, tough shit.” It was the best Hanukkah ever.

With its introduction in the late 1970s, the Atari Video Computer System—later re-branded as Atari 2600, to place it squarely in the shadow of the more dazzling Atari 5200—transported home video-game graphics into the almost figurative, but still very weird and blocky future. With its amazing four kilobytes of game memory (which is only slightly less memory than a “Mr. T In Your Pocket” talking keychain), a video game tennis player was no longer abstracted into an elongated dash; now it could be rendered as a stack of squares with insect legs. In considering the Atari’s many other innovations over TV Pong, one could cite removable game cartridges, or the joystick, or full-color (i.e., more than two) graphics. But, for me, it will always be the red “fire” button. Besides exploiting and satisfying certain autistic tendencies for repetitive tactile stimulation, the fire button meant I could fire. At other things, like aliens or large rocks. This was an unprecedented, almost God-like power. In Combat, I could fire a shot nearly halfway across the screen, or bank one off a wall and destroy my brother’s tank in a glorious explosion of seven pixels. Or, in games like Yar’s Revenge, I could, as Yar, swiftly and continuously mash the red button and fire cannons to, I guess, exact my revenge.

The joystick’s distinct shape provided me with hours of sophisticated entertainment, especially as I blindly turned the corner of sexual awareness. When Beth Rubenstein came over to “play Atari” in our renovated basement, our gaming would always quickly deteriorate into marathon sessions of hard, closed-mouth kissing—because tongue kissing was disgusting—followed by hilarious hijinks such as me chasing Beth around the weight bench with the joystick tucked between my legs, like Jane Gumb trapped in the world of Tron.

I’m not sure who would have been more disappointed to discover that last fact: my parents, who tried their best not to raise a pervert; or my brother and sister, who had no idea they were playing Activision’s Pitfall with my surrogate boner.

The joystick’s distinct shape provided me with hours of sophisticated entertainment, especially as I blindly turned the corner of sexual awareness.

In 1982, other, more powerful gaming systems were already overshadowing the Atari 2600, like Intellivision (with its sizzling hot teen-icon spokesperson, George Plimpton) and ColecoVision. But it didn’t matter because I had something those other systems didn’t: Pac-Man. So great was my love for Pac-Man, I was willing to overlook the very obvious fact that Atari had taken an already simplistic video game and managed to degrade it in so many ways the game felt like a tremendous prank masterminded by a disgruntled Russian computer programmer. The escape tunnels were reoriented on the top and bottom of the screen. The dots were turned into dashes (!), and some of those dashes were so long they had to be eaten in two gulps (!!). The music was stripped out entirely, replaced with a four-note emergency signal. But most disorienting of all was the hero: Pac-Man had been re-imagined as an octagon with a constantly chomping, greedy slot for a mouth, and designed so large he could scarcely squeeze through the maze. Because of Pac-Man’s macrocephalic condition, he was incapable of rounding corners, but Atari found a brilliant workaround: Pac-Man would always face west. When pushing the joystick to the right, Pac-Man simply backed into dots and energy blocks, his mouth still opening and closing rhythmically, as if crying in pain from shoving things into his rectum. Underscoring Atari Pac-Man’s overall cognitive disorder, the home game replaced the familiar rhythmic dot-munching soundtrack with a flat, repeating “bonk” note—its own digital Tourrette’s bark.

Of course, none of this discouraged me a bit. I played Atari Pac-Man around the clock, often hooking the reset switch with my foot the instant my game ended so there wasn’t a single moment I wasn’t playing. Atari unlocked something inside me that couldn’t be sealed up again. The first time I came into some money—at my bar mitzvah—I invested the entire sum of my pay-to-pray windfall in an Atari 5200, a system clearly twice as good as the 2600. It wasn’t until I unpacked the box at home that I discovered it could only be connected to a color television set. This was strictly forbidden, because my mother had seen a report on P.M. Magazine that video game systems can cause both epileptic seizures and color TV burnout—and my mother was not willing to sacrifice the health of her set. The 5200 went back in the box—slowly, melodramatically—and was returned the following day. My bar-mitzvah money was re-invested in a pair of ash gray knock-off Capezios from Thom McAn, and a knock-off Members Only jacket from a knock-off Merry Go-Round clothing store in the mall. The Levins and the Joneses remained leagues apart.