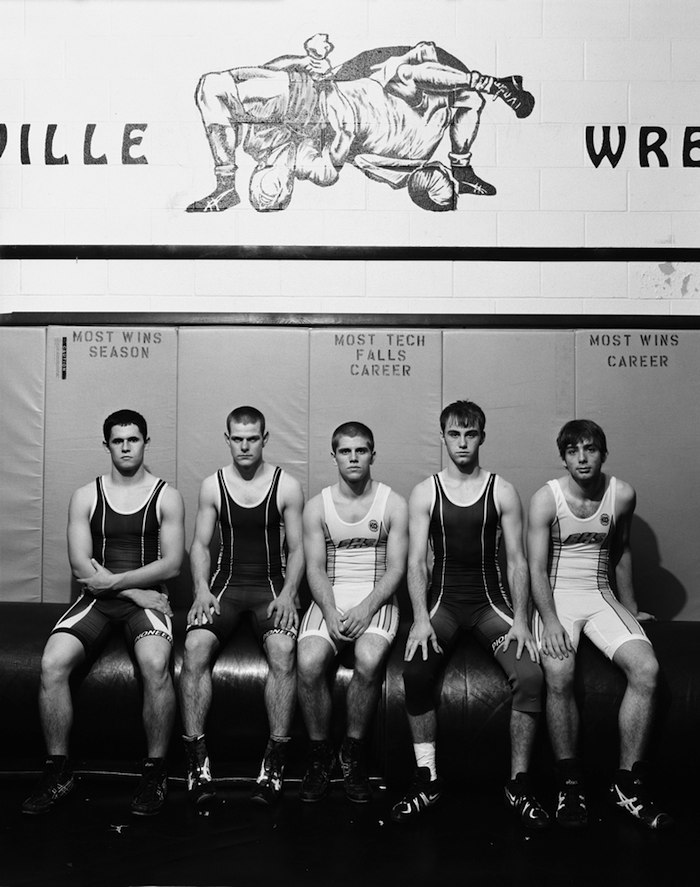

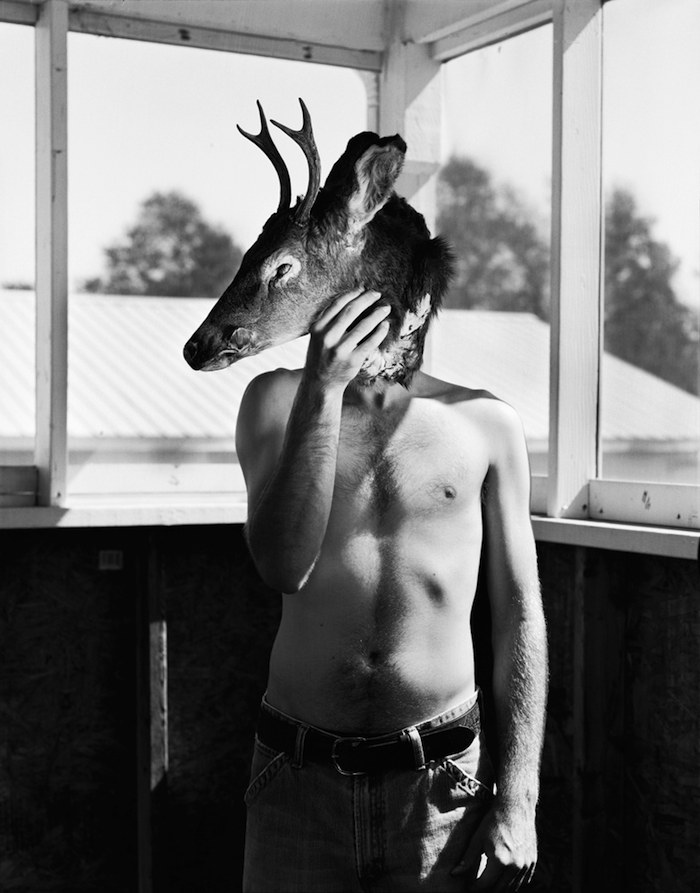

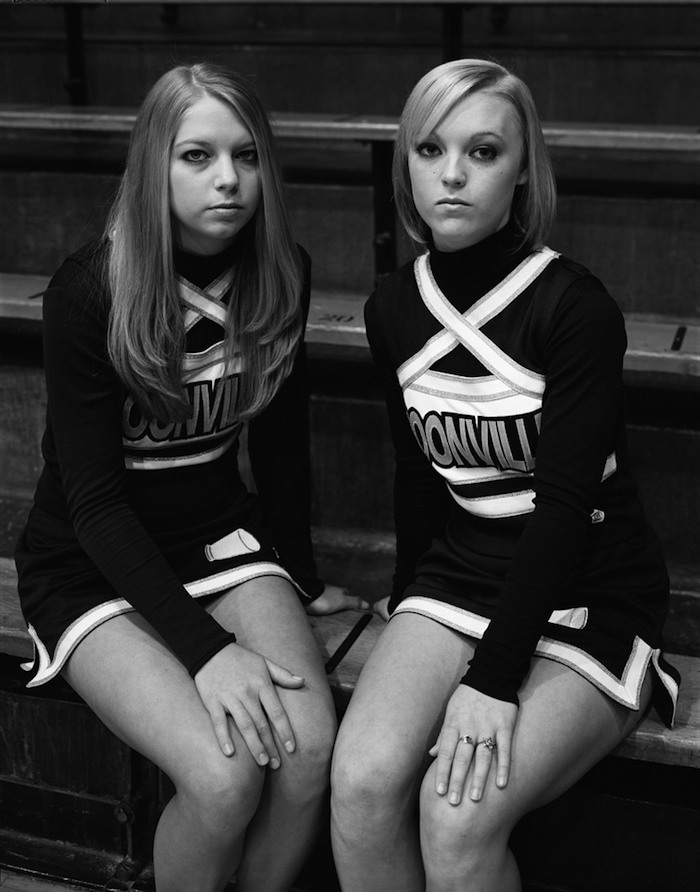

Photographer Timothy Briner spent seven years on “Boonville,” which takes place in six towns in the U.S.—six different towns named Boonville where Briner lived for periods of time and shot portraits of private lives, overpasses, and wrestling squads. In Briner’s pictures, all Boonvilles are the same and none of them are. It’s a unique road trip across contemporary America.

Briner was born in Indiana. He currently lives in Brooklyn, and is represented by Daniel Cooney Fine Art in New York. A two-person exhibit, “Present in the Rearview Mirror,” with photographer Matthew Gamber, opens this week at Caption Gallery in DUMBO. Boonville was underwritten by Cannery Works, a New York-based non-profit arts organization. All photographs copyright and courtesy the artist, all rights reserved.

When you first visited Boonville, N.Y., what hooked you? How did your visits to the other Boonvilles come about?

I first came across the town of Boonville during the fall of 2003. It immediately had an effect on me. I felt a sense of mystery amongst the town and its residents. I grew up in small town in northern Indiana, and we used to toss around the term “The Boonies” quite a bit. The name of this town hooked me pretty quickly. I created a small body of work during my first visit, but it took four years for me to return to Boonville and to visit the five other towns named Boonville for the first time. I referred back to that small body of work for years, never forgetting that town and its hold on me. In 2007, I left for Boonville, Miss., and after one year, I had lived with residents in five other towns named Boonville across the U.S. The series evolved quickly over the first month I was on the road, and continued to change as I continued across the country.

There’s a lot of isolation in these pictures, more for me than the subject—I’m intruding into these towns, into these moments. Does that sound right?

Yes and no. If that’s how you feel, then I think that’s how you are supposed to feel. For me, I wasn’t attempting to have the viewer be an intruder. But I was projecting my own feelings of isolation and my memories of my own hometown onto my subjects, or onto my ideas. I believe that once it’s on the wall, or in a book, and depending on when and where it’s looked at, the viewer’s perception and reaction to the work is unique and out of my hands.

When you’ve been hanging the pictures or editing the book, do you see these portraits individually, or as an ensemble?

They were created in the form of a series, but I do look at each one individually. For me, they all have a very personal story attached, so I can’t help but separate them, although they have this connecting thread.

How much of Boonville’s America is your own?

This project was strongly based on my own personal experiences. I chose very carefully what to show and what not to show. So I guess I would say that all of it is my own, or was.

What are you working on now?

I’m actually opening a two-person exhibit of new work this week at Caption Gallery in DUMBO during the New York Photo Festival, alongside photographer Matthew Gamber. The show is titled “Present in the Rearview Mirror.” The work I am displaying is from a new project titled “Arrangements in Shades of Gray.” My mother says it’s “very different,” and on the surface it is. This body of work examines the way in which we give and receive (or view) information, specifically through the digital screen.

Lately, I’ve been inspired by street photography, and photographers, in America from the 1930s to the ’80s. “Arrangements in Shades of Gray” is a series of street photographs that I have taken on a mobile phone since returning to Brooklyn from Boonville in 2008. I then go into the studio and re-photograph the screen (with film) in which the camera-phone photos appear, and would ultimately be disseminated through. The final gelatin silver prints relay the power of the traditional photograph, but unmask the relationship between the photograph, the viewer, and the digital screen.