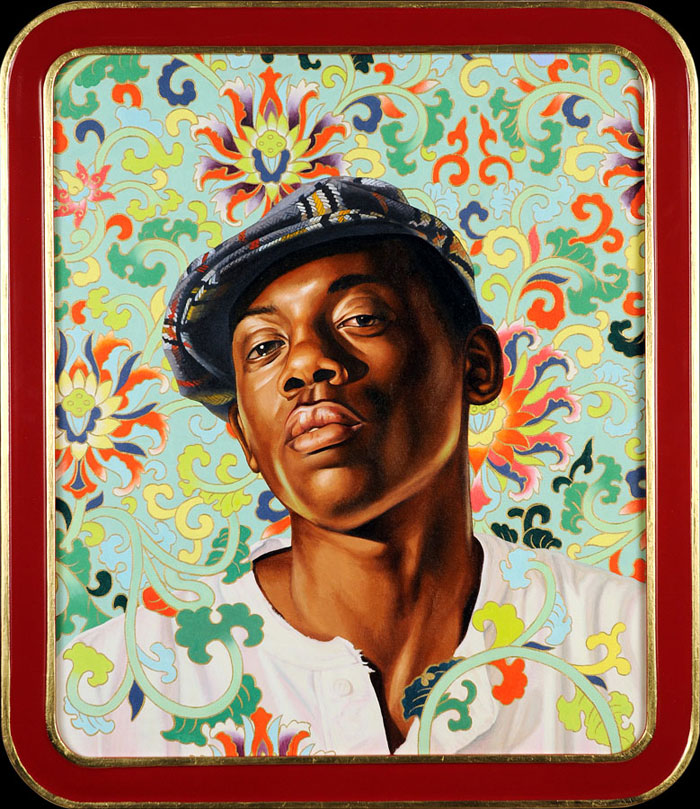

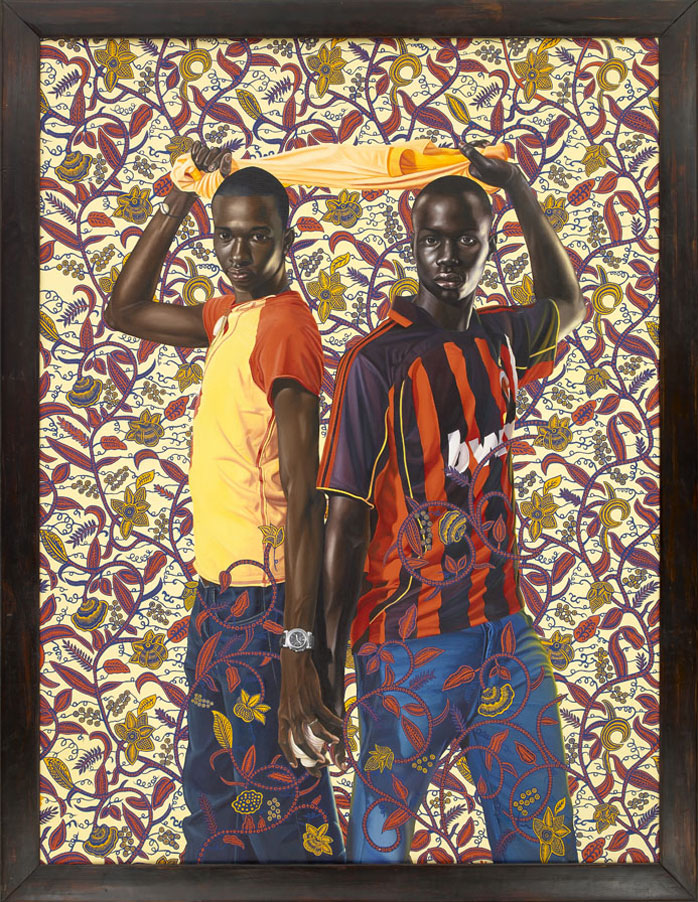

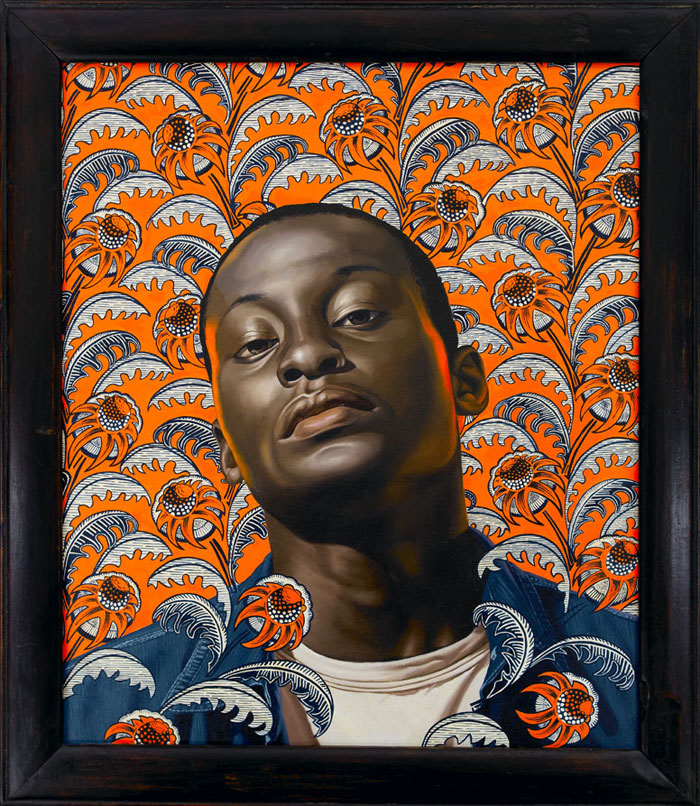

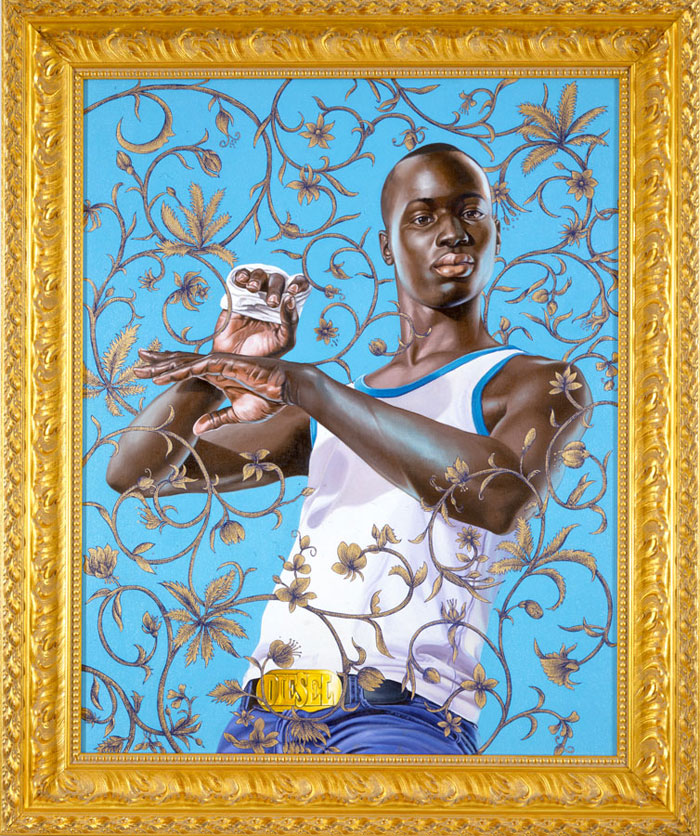

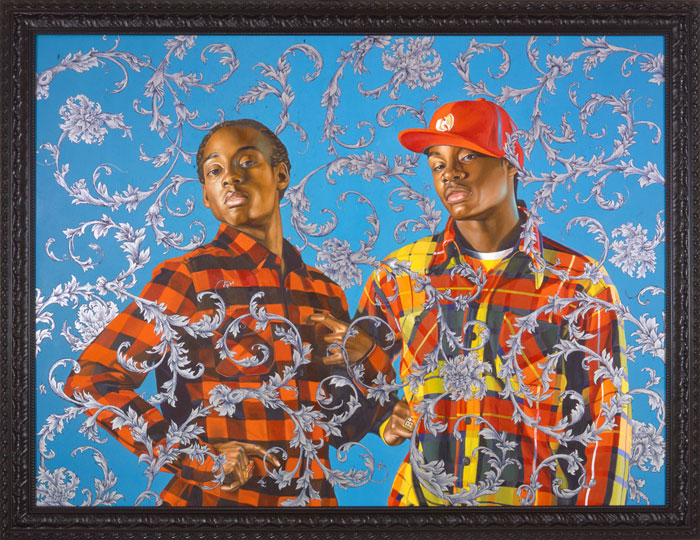

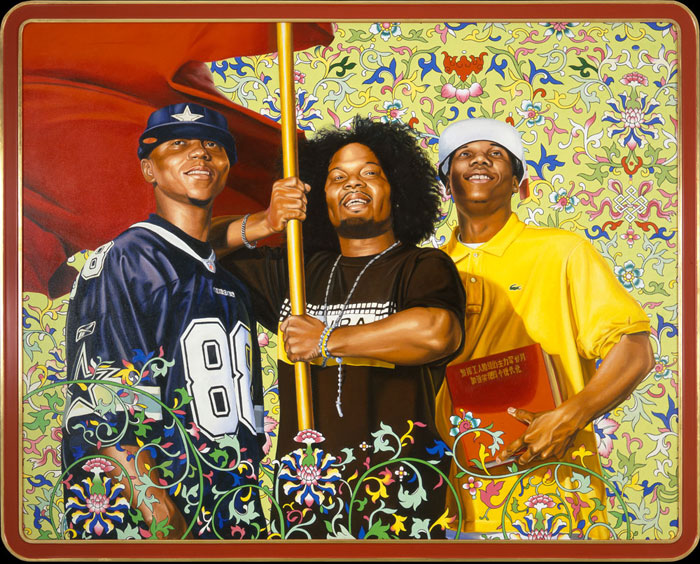

Kehinde Wiley’s paintings marry strange bedfellows: the 18-year-old black man on his way to the train and 18th-century religious portraiture; the National Gallery and New York City streets; sneakers and traditional Senegalese textiles. Cultures collide, but according to Wiley, that’s to be expected—it’s happening around the world, easy enough to see as long as you don’t look for it on the nightly news. More proof will be available at The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York when Wiley shows his long-term project, “The World Stage” this July.

Wiley received his MFA from Yale in 2001, and later did a residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem. His work is in the collection of the Denver Art Museum, the Columbus Museum of Art, the Kansas City Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, the Oak Park Public Library, the Studio Museum in Harlem, the Walker Art Center, and the Virginia Museum of Fine Art. Wiley is based in New York.

All images © Kehinde Wiley, courtesy the artist.

Can you explain your influences and how you address them in your painting?

Most of the paintings I make refer to very specific paintings that existed historically. That comes out of my own passion for the history of art, and started when I was a kid. I would go to collections in California where I grew up. There were very few historical collections, but there was one that included quite a bit of 17th- and 18th-century portraiture. That was an early influence and something I came back to as an adult. It’s very much about a passion for painting and, I think, about the strength that painting has as a symbol in the world. In some sense, I’m sure I’m attempting to manipulate that symbol, occupy that space, and put something new there.

So how do you understand the symbol of painting?

Painting points to some of our highest ideals as a society—the ability to honor great moments in the past, great people. The history of painting has to do with the history of those people who supported art, generally the church and the state. So [these paintings] were really great propaganda tools to communicate the importance of the dominant powers at that time. By and large, those values in regard to organizing people and religion haven’t really changed. While we live in a much more internet-driven, televisual-arts world where communication is a lot more complex than colored paste and sticks, there’s still a very strong relationship between power and painting.

And that’s apparent in the arts today?

I think the art world, by and large, is a society of people who are, sure, interested in creating evocative images concerned social justice, progress, and so on, but also who are privileged and consuming high-priced luxury items. I think it’s the job of the artist to realize the relationship between what he participates in and how that work comments on itself. That’s part of the reason why so many of the people pictured in these paintings don’t really come from that privileged world. Many times you’ll see museum attendance altered quite a bit by exhibitions [of my work] because people see people on the walls who look like them.

You’ve shown work at the Brooklyn Museum, the Smithsonian, as well as countless galleries. Does manipulating traditional symbols in art take on an even deeper power and intensity when your paintings show up in museums?

Museums have always been the guardians of culture. They’re distillers of what we, as a culture, believe in. I think that’s what’s so revolutionary in some ways about these paintings being in museums: Our culture has evolved to a place where we can actually accept [my work] on museum walls. It takes a certain amount of progress in American viewership. I think it also speaks to the very real need in our culture to see a much more accurate depiction of what’s out there and what’s possible.

How do you find your models?

Most of the time I go onto the street with a bunch of friends—it helps people to feel like this is a lot more serious. In big cities, people are often uncomfortable—I get the fact that no one’s expecting to end up in a 12-foot painting on a museum’s walls when they’re approached on the street. I think there’s something crazy and magical about it. It takes what was usually a very important social occasion, where powerful people commissioned famous artists to create their image, and turns that into a moment of absolute chance. That juxtaposition between chance and the heroic statement of the painting evokes the history and strength of portraiture, but it also empties it out.

Is your process or your method democratic in that respect?

I guess you could say it has a very democratic or social appeal but conversely, there’s something very elite and removed. If I don’t recognize that, I’m fooling myself. The average 18- to 35-year-old young black man in my paintings, by and large, may not be able to afford these paintings. I think what’s going on here is a much more complex critique of American society than the one-to-one relationship between what’s right and what’s wrong and what’s redemptive and what’s not.

Do you consider the work subversive, then?

I guess the question about whether or not my work is subversive, presupposes the question—”subverts what?” What I’m trying to subvert has to do with the over-determination of painting and its history. I’m trying to find new ways to make that style of painting matter today. In that sense I’m subverting the death of painting. I’m not entirely sure I’m subverting any economic or social dynamics because my paintings in some ways draw on very negative truths with regards to the reception of painting.

What are these “negative truths” about the reception of painting?

We privilege the easel painting instead of an act of sculpture from Africa or Oceana. Why is it that Eurocentrism is still the dominant material means of recognizing what’s culturally valid? In my own history and in my own story, I happen to really love and enjoy this painting. I have to come to terms with not only the beautiful and terrible parts of it, but the fact that I, as an artist and individual, have something unique to say about that.

You traveled and worked outside of the U.S. for the work in your upcoming show at the Studio Museum. Can you talk about the project?

The Studio Museum in Harlem this July will be launching the second platform of what will be a multi-stage project called “The World Stage,” in which I travel around the world and collect models much in the way I do here—by street casting. As opposed to using the history of Western art [as a format], I used public sculpture in each of those cities. For the show at the Studio Museum, I was in Lagos, Nigeria, and Dakar, Senegal. In those cities, I found public sculptures that were erected in the ‘50s and ‘60s, after the independence of those nations. Much of that sculpture represents a redefinition of a nation: very hopeful images of the future and also very descriptive ethnic depictions of a people. It’s interesting to see that juxtaposed with young Africans from the contemporary African-urban street; their look and feel has nothing to do with what we see televisualized. In fact, a much more accurate context for these “worlds in collision” is how [the model’s] jerseys and sneakers collide with more traditional patterning. That’s similar to the paintings I’d done before, [because] the sculpture is also very stately. The models are still mostly people of color, but the intentions behind the work have changed conceptually.

Is that why you went, because of a sense of difference between the urban United States and other nations?

Much of why I went had to do with the thing I’d been charting around American culture: What is the look and feel of young America in its urban streets? So much of that is influenced by people and races outside of America so, conversely, I decided to pack my bags and follow that line of inquiry onto its own turf. Also, it opened up a broader range of possible influences and motivations. Many of the backgrounds of my paintings in the past have come from world culture, but with “The World Stage” I was able to really go through the marketplaces and find, like in Senegal, really amazing West African textiles, which then became these fields that the models inhabit.

Do you plan to continue traveling and showing the work you did in other countries?

Yes. The last trip was to Rio, where we went to favelas [slums] and sourced models. That show will be opening in Los Angeles in April 2009. There will be a trip to Turkey and one to North Africa—Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco. The project is going to have many platforms and conclude in a massive exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum in 2010-11. We’ll take the best of each of these locations and present “The World Stage” in its entirety.

Place to place, is the way people reflect their local culture and a world culture consistent or varied?

That exactly is the point of the work in some ways: to create a system, a type of grid, that gets overlaid in each of these locations. The system is the same for each, but what gets revealed is that unique local color. It’s a very irrational and very unwieldy thing to do—to go to these places and do this street casting.

I like the idea of trying to parse a local character. It’s something that’s really discouraged socially.

There’s something incredibly colonial about it. Historically, so much has to do with a type of capturing—bringing home images of the Empire.

It seems politically fraught.

Yeah, and as opposed to running away from those places, it’s often more fruitful to ask yourself what’s possible within them. Many people in America assume a political corrective in my work, which in many ways doesn’t exist. I find those softer-underbelly pieces of what we consider to be acceptable socially and give them a second glance.