When I get the money together to commission a portrait of my wife, Stephen Earl Rogers is on the shortlist I’ll call. Rogers is a figurative artist, working within the long tradition of representational art. Each painting has its own set of concerns and ideas, some formal and others more conceptual in nature. He is held in permanent collections in the U.K. and United States, has exhibited many times at the National Portrait Gallery, been sold through Sotheby’s, and shown at Christie’s. All images courtesy of the artist. All images © Stephen Earl Rogers, all rights reserved.

How has your work developed over the years? Have you always striven for such realism?

If I am honest, I have basically always tried to emulate Holbein. If I could achieve such penetrating realism with such economy I would be extremely happy—I’m still striving.

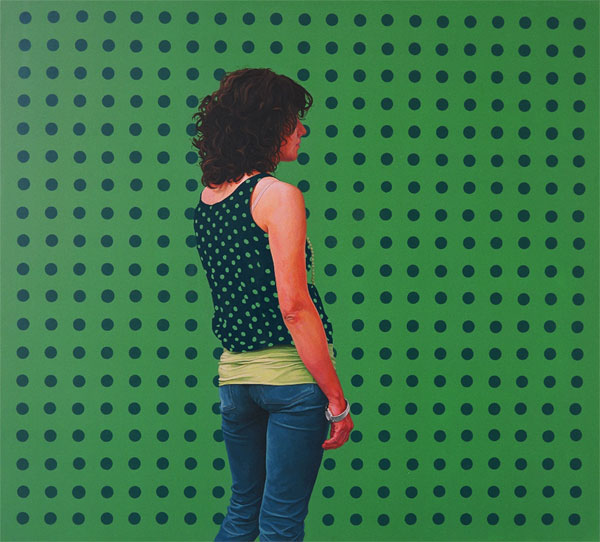

Down the years, however, I have had many influences, not all of them realists by any means. I am always excited by Degas for his color, composition, and incredible mark-making. The delicate linearity of Indian court paintings has informed my work, and I’ve been inspired by Peter Blake. I have also learned an awful lot from the richness of an Ingres grey and the clarity of light in a Hammershoi painting. My work has definitely become more “real’” over the years, but I have been aiming to make the work fuller. Technically I have come a long way, but I am still not where I want to be; it has started to get very complicated in this regard. But beyond this, it is the constant process of discovery. Looking at the way pattern is used in traditional Japanese art, for instance, led me to a new approach.

There seems to be such insouciance about your subjects, or perhaps just a sense that you know them well and that no one really cares they’re being painted. Do you paint friends?

I have painted friends, but a lot of my work is commissioned. When I am going to paint someone, I do make a point of trying to reach a stage where they are genuinely relaxed and comfortable before we start. People also do get bored and drift off during a sitting, which sometimes helps.

Where does a painting begin for you?

An idea occurs to me and I develop it in the sketchbook.

Where do you look for inspiration when you’re feeling dry?

I can’t remember the last time I ran dry. I work with medieval technology, so things take a long time—I am always playing catch-up with myself: so many ideas, so few of them realized yet.

At least in the pictures I’ve seen, context doesn’t seem very important to you if we’re to understand who these people are—there’s no background, no environment. Can someone’s figure and expression give us all we need?

I have to make a distinction here between commissioned portraits and my own paintings. When I paint a portrait, I have no interest in surrounding my sitters with the paraphernalia of their lives, interesting though it might be. Certain environments can lead to certain assumptions, which, to my mind, detract from a true understanding of the subject. I am, however, interested in relationships between people—”The Oswestry Connection,” for instance, is given a type of context by the friendship that is evident within the group.

When I make my own paintings, growing from my own imaginings, context is important to me—but in the sense that I want to control it. The pictorial environment is what I concern myself with. A deep understanding of the sitter is not necessary: They are a component within picture and are chosen because they hold something that I want to lend to a particular painting. The focus might be purely about the formal concerns of composition or it could be something not immediately tangible that will percolate into the atmosphere of the painting.

What are you working on at the moment?

I am starting to develop a body of work that will hopefully realize some of my ideas about how pattern from different cultures and historical contexts can be employed within figurative painting. To illustrate: I have painted a rusted, old, mass-produced Honda motorbike, which is going to be set against a patterned background taken from an exquisite, national treasure of a kimono, held in one of the Japanese museum collections. This is probably the only still life that I plan to do for this particular body of work. I also plan, as part of this series, to create a painting that at first appears to be just a spectacular mosaic of pattern, but on closer inspection reveals figures subsumed within the pattern and engaged in some kind of ambiguous activity. This, at least, is the starting point. I am looking forward to developing this idea fully.