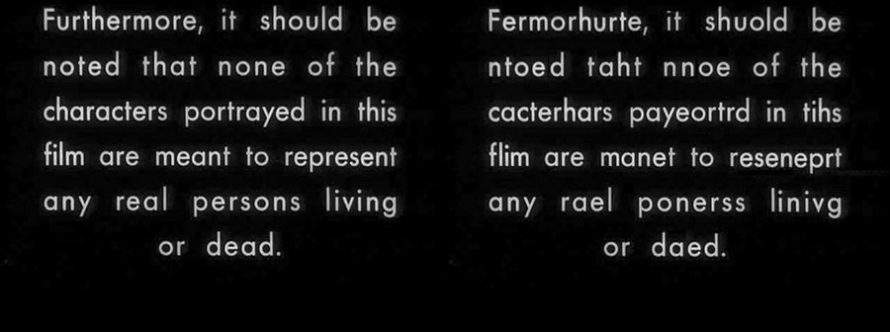

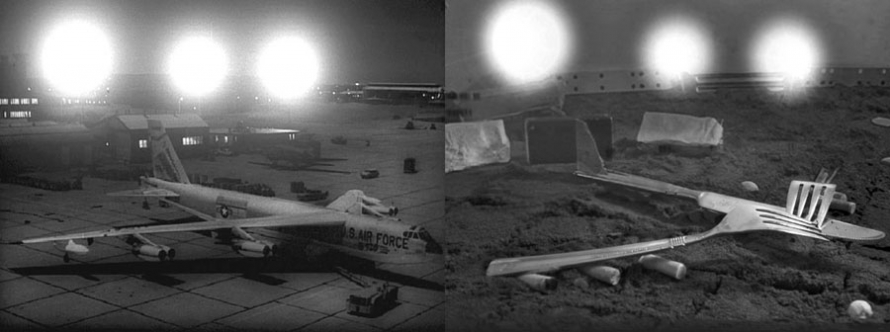

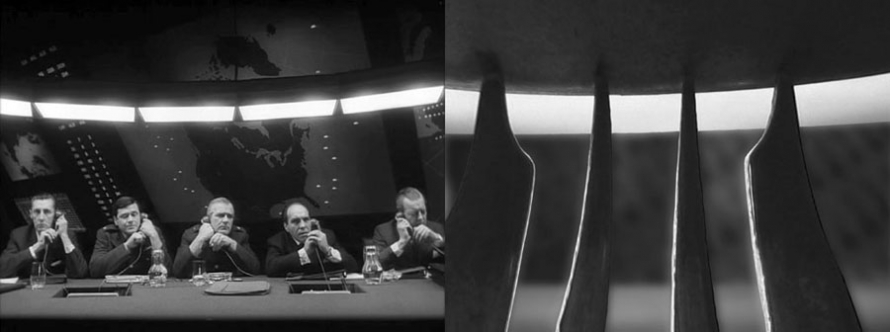

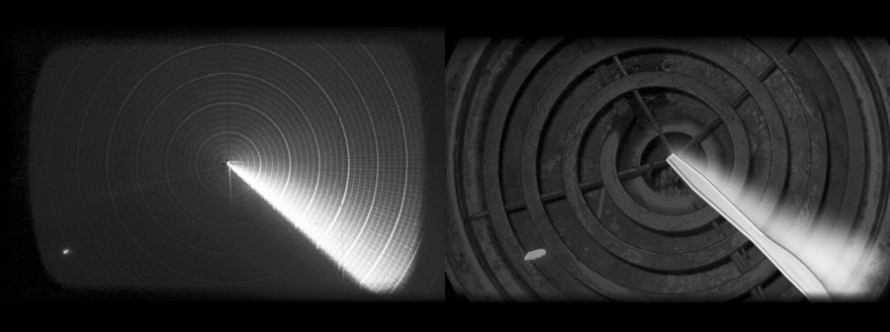

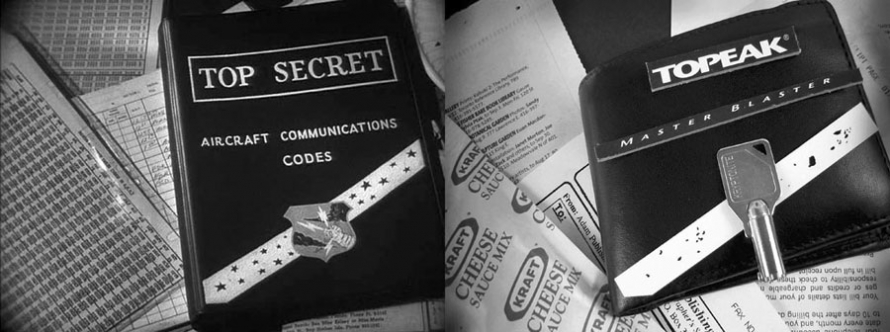

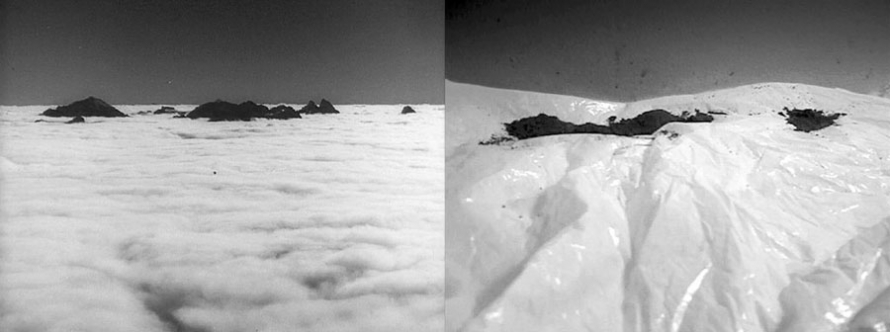

In Dr. Strangelove Dr. Strangelove, Kristan Horton imitates the satirical movie Dr. Strangelove and creates a new world for the film—silverware become an airplane, plastic and coffee grounds become the sky. The connections between Kubrick’s film and Horton’s photographs demonstrate the power of familiar sights, sounds, ideas, and objects to change the way we look at cultural icons.

Kristan Horton was born in Canada in 1971. He studied at Guelph University and the Ontario College of Art and Design. He has had an international exhibition career since the late 1990’s including Glassbox, Paris; ZKM, Karlsruhe, German; Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki, Finland; and Inter Communications Center, Tokyo. Previously shown at Jessica Bradley Art + Projects, Dr. Strangelove Dr. Strangelove will travel to Vancouver’s Contemporary Art Gallery in July, 2007.

All images courtesy the artist. All images copyright © Kristan Horton, all rights reserved.

How did the Dr. Strangelove Dr. Strangelove project begin?

I don’t have a television. When a friend dropped off a VHS version of the film to the studio, it became the only thing to watch on the monitor. In two and a half years, I watched the film over 700 times. My perception was saturated by the film, and this caused me to respond to it. You can see this among Star Wars fans that log hundreds of viewings and go on to make Storm Trooper outfits for themselves in their living rooms. It’s a need to manifest [the reality of the film] in life. That marked the beginning of the project. I began to see relationships [between] the film present and the way I was working.

Are you attracted to the film because of its themes?

I’m interested in [art and representation] that attempt to negotiate the epic concept of nuclear war with our daily lives. For example, War Games (1980) centered the drama on video games, as if we could understand better “lives in the balance” in terms of a joystick. This recasting and reshaping of the Cold War’s drama echoed in my work as a rearrangement of my quotidian life. That we can reenact a traffic accident we saw by placing the salt and pepper shakers in a certain way [suggests] we can bring that moment alive on the table.

Film is a moving art, but your Dr. Strangelove Dr. Strangelove series requires that these scenes be frozen or stopped. Why did you recreate still frames from the movie?

The project began with an intention to animate [by creating] an animated film. But it was the still that attracted me. The comparison was the exciting part. We can take as much time as we like in making the comparison. Time is on our side, not whizzing by at 24 frames per second.

Is there something about Dr. Strangelove specifically that made it exciting to compare recreated stills with stills from the film?

It is a film that exploits composition. The film is in black and white, there is relatively little camera movement, and the sets are minimal. There’s a tension in my mind about the reality of war and its representation. Perhaps we don’t want to think of war in terms of aesthetics. But really, that is all we have to work with. Anyone familiar with propaganda can confirm the seriousness of representation.

Why recreate these scenes with common household objects?

The mundane reconstructions signal the conditions of my immediate life. [It’s like when you] use a stick as a gun, or use your hand as the beak of a bird. Specific contexts illuminate the scope [of the object]. Mundane items are an index of a certain reality, just as the props in the film are an index of a certain reality. A confused context is created by the repositioning of fork and knife to resemble a B52 bomber. It’s the same in B movies when a pie plate substitutes for a UFO. It’s ridiculous, but it works.

Do you feel like your photographs offer new imagining of the film, or should the familiarity of the objects you use bring us closer to the original work?

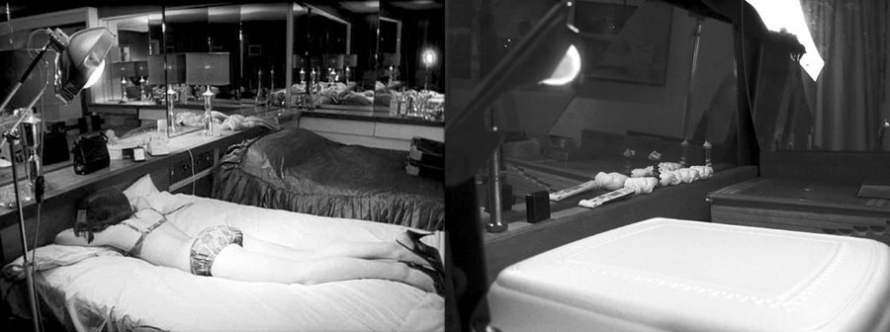

The mundane objects I use in the Dr. Strangelove Dr. Strangelove project are positioned, rotated, lit, and framed until they begin to register as objects in the film. This pulls the objects away from real life at the same time as it pulls the film away from the screen. The mundane identities of the objects I use for Dr. Strangelove Dr. Strangelove are left intact. I wanted what they represent to be present in the work. They retain their status as Coke cans, coffee grounds, and forks. The B52 bomber is itself a prop, a model of an actual B52-bomber. In most cases, the Dr. Strangelove Dr. Strangelove project compositions are themselves an imitation of an imitation.

How do you decide which stills or moments to recreate?

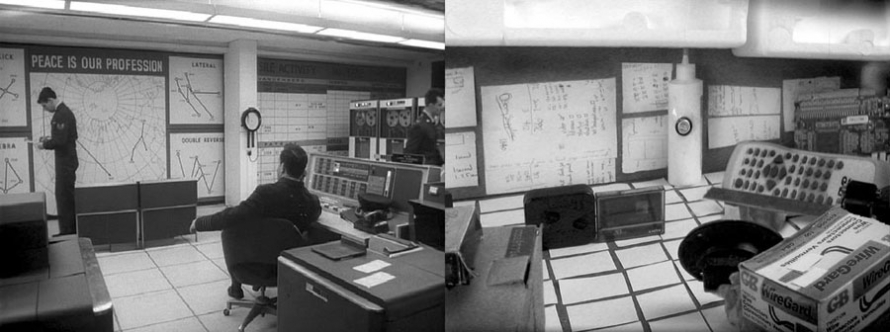

For the majority of stills, it is a matter of capturing a satisfying representation of the compositional variations. In addition, I was interested in recreating certain sequences such as the big board behind General Turgidson which is relatively identical yet there are six of these images. The only significant change occurs in the light patterns that are indicating the flight paths of the B52 bombers. Elsewhere, nearly identical stills are imitated nearly identically. My interest was to employ and find as many strategies of imitation and other relationships that were happening there.

Why are there no people or characters in your recreations?

My mandate is not to rely on an arbitrary system that would eliminate all people from the work. I am more interested in creating my own system by making observations and working from those observations. By watching Kubrick’s films repeatedly, I observed that actors known as “extras” took on equal importance as objects for the filmic compositions. This is not unique to Kubrick, but he does use it with a rather numbing simplicity. Full Metal Jacket features a shot that reads like the stages of infinite regression. Underwear-clad recruits line up at bedside creating a human corridor. He uses actors as objects for the composition of the shot. I have tried to discern this logic at work, for example, and go with my intuition about who is a character and who is a prop.

How does your work connect to your understanding of the film’s message?

Imitation, mediation, rivalry; thinking about where our desires come from. We can think about this in terms of the Cold War arms race. We have a competition of ideology, of technology, and the preservation of a way of life. For example, “Peace is our Profession” read the signs on Burbleson Air Force Base; U.S. strategy of containment; borders; the danger of “Make them like us”; imitation as a colonizing force; infiltration; double agents. It feels like language to me. It seems like the same struggle to make meaning where words and things and agreements and multiple perspectives are all competing.