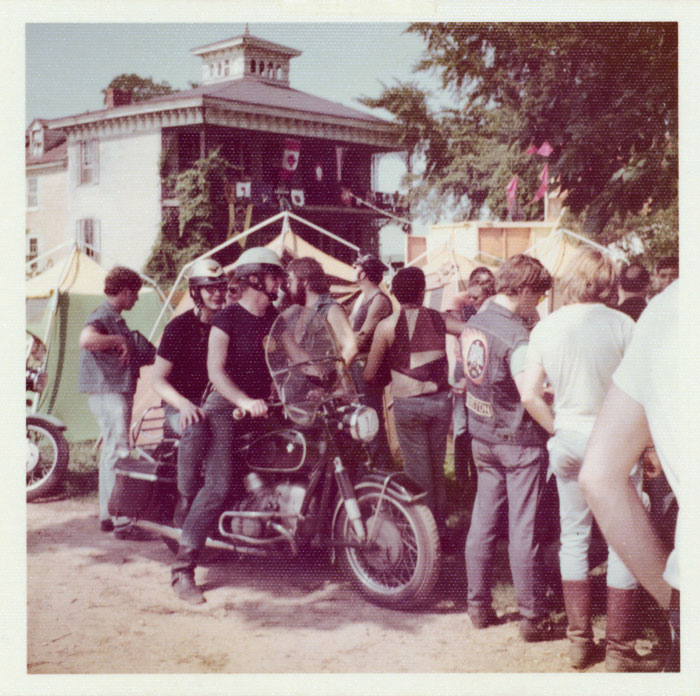

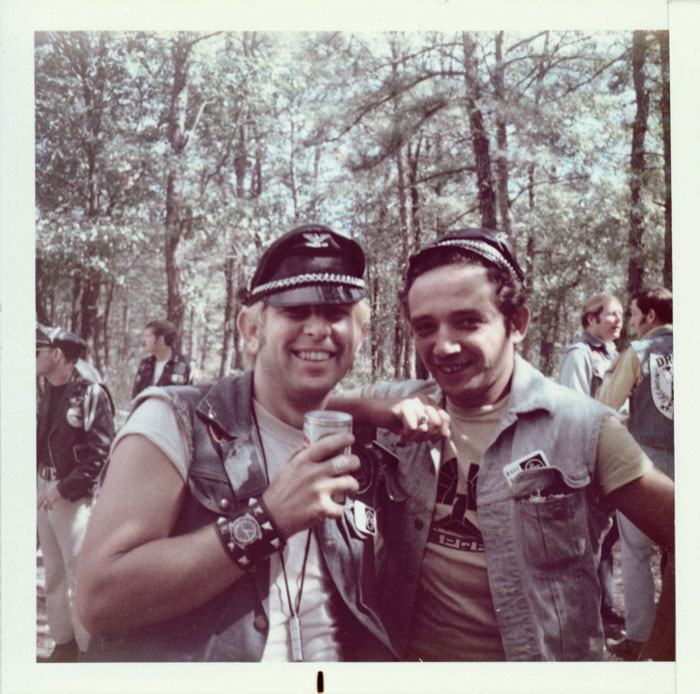

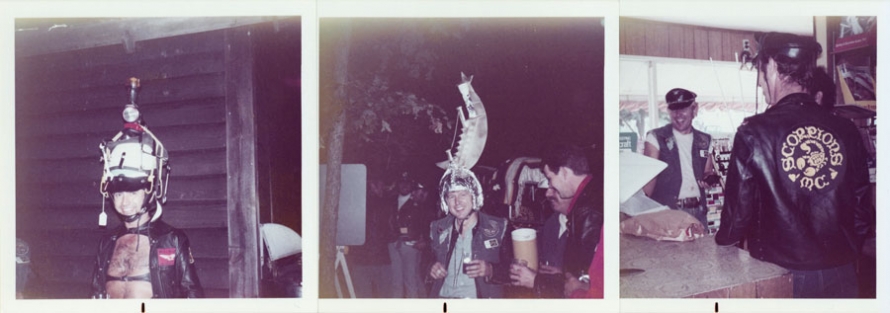

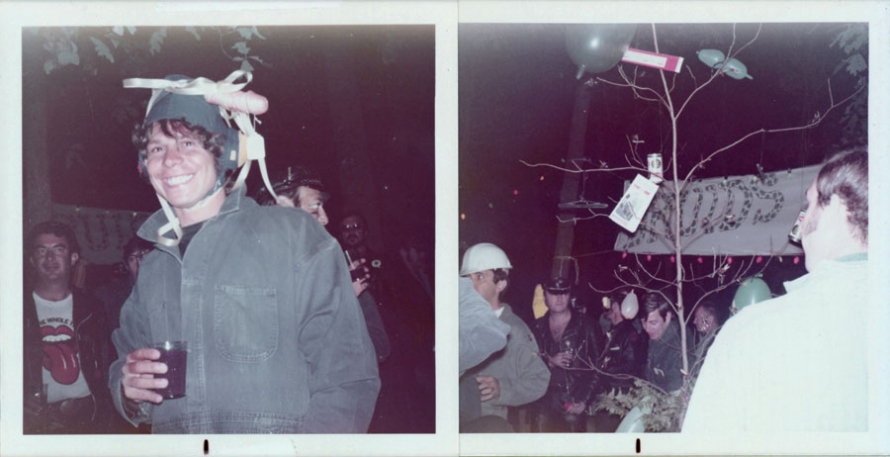

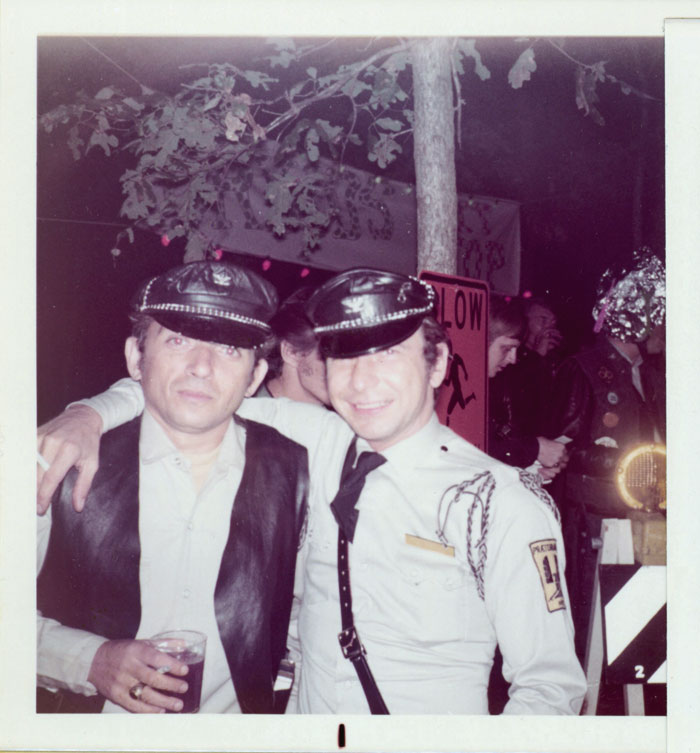

Gallerist and poet Scott Zieher doesn’t have to look hard for art—it has a way of showing up on his doorstep. At least that’s what happened with this photo album he found of snapshots from the gay biker scene of the 1970s. Zieher’s discovery reminds us that treasures, like subcultures, exist right under our noses—not disguised, just overlooked.

Scott Zieher is co-owner of the contemporary art gallery ZieherSmith. He was winner of the Emergency Press 2004 annual contest for his book-length poem, VIRGA. A second book, IMPATIENCE was published by Emergency Press in 2009. His poetry has appeared in The Believer, Jubilat, and The Iowa Review. He has lived and worked in New York City since 1992.

How did you end up finding and publishing a book of snapshots of gay bikers from the ’60s and ’70s? Who did the photos belong to?

I found them while doing laundry in my apartment building. I had no knowledge of the man who owned them, but my superintendent told me he’d passed away and that he had lived on my floor. There was a large glass container of coins the super wanted to keep, otherwise the rest was up for grabs—it appeared that the man’s entire apartment had been discarded. From among the rubble of furniture, clothing, a potted plant, I plucked one, lone, standard file-box. I was mesmerized for over an hour while looking through the box back upstairs in my apartment. By the time I went down to put my clothes in the dryer, the heap was gone, bagged, and waiting on the sidewalk for the sanitation department.

What have you learned about the owner or the gay biker scene in the ’70s?

Other than a few cursory searches, I never really pursued the facts of the man or the groups depicted. It might seem odd to some, but I didn’t investigate any further because this ghostly gift seemed all the more intriguing and miraculous without the details. There was no biographical information, so I have no way of knowing who shot the photographs, or if the very compelling man who appears throughout the archive is the owner, or if the photographer was the lover of that man. If there were survivors, they did little to preserve or destroy the owner’s legacy. If it was private, nothing was done to keep it that way. I now treasure it as an anonymous fill-in-the-blank scenario. A few details came out during our exhibition of the photographs, but the scene was pretty deep underground.

The introduction to the book claims there’s a connoisseurship to finding things. How does one become a connoisseur of found objects?

More than anything, I think being in the right place in the right time is a good part of that connoisseurship—a certain way of glancing at the refuse in New York, looking underneath the tables in a flea market or antique store. I think we make our own luck and approach the found object as something poetic and blessed.

I read a great article about a dealer in antique clothing, rummaging through disused old buildings out West, often finding treasure stuffed in the floorboards and vents, having been stuffed into cracks to prevent drafts. Yesterday I picked up a spiral-bound scrapbook in front of my apartment building. It was the guest book for a wedding, and there were children’s drawings scattered all over the street. A story unfolded and it was haunting and sad.

Did you have a particular connection to the subject? Do you now, having found the photos?

I’m straight and married and have never driven a motorcycle, but I’m a poet and a contemporary art dealer, so I certainly have exposure and sensitivity to aspects of gay culture. For that matter, I first saw Kenneth Anger’s films and read his books as an undergraduate in Milwaukee in the mid-’80s, and came of age in an era when gender and sexual politics were pretty rampant issues at the university level. And the poets that made their most indelible impression on my younger self were often gay—Whitman, Crane, Ginsberg, O’Hara. Suffice to say one can’t call oneself a decent poet and not find some affinity with a good portion of the predominant contemporary canon. If that’s affinity, then I suppose the answer is yes.

But more than iconography or politics, I have always had a fondness for vernacular photography. The fact that a completely unassuming amateur captured these weekends is what appeals most to me. It’s a marvel how much information he managed to capture in such an offhanded way. These photographs comprise a gorgeous microcosm. It’s unmistakable.

These photos are clearly treasures, but what makes them art?

Personally, I don’t think there’s any question that these photographs are art. The photographer had a really great eye and there’s not a mediocre composition in the bunch. Their artistry is as important as their socio-political relevance, but in the end I would argue that the accidental artist of the snapshot variety is a difficult entity to quantify or qualify. Folk photography is an oxymoron, but the casual, middle-class snapshot has great appeal to today’s young artists.

Which photo is your favorite? Have you invented a narrative about any of the images?

I have several favorites. I particularly like the photographs that show the camaraderie at its best, with several figures, arm in arm, seeming to have a great time. I also think the photos of the hat contest are pretty amazing.

Do you have any sense of conflict or anxiety over publishing a book of someone else’s personal photos?

I don’t. I think these photographs should be shared. They seem to embody something really special from the past. So many people are so delighted by the book and exhibition that I think the decision was the right one.