Environmentalist and photographer J. Henry Fair wants you to stop buying plastic bottles, driving to work, and leaving the lights on. With government controlled by polluting special interests, Fair believes we must vote with our dollars to curb environmental ruin. Whether you agree with his prescription or not, the diagnosis established in his beautiful and terrifying flyover photos of environmental devastation cannot be disputed. Work from his forthcoming book, The Day After Tomorrow: Images of Our Earth in Crisis, is on view at Cooper Union Jan. 20 to Feb. 26 and Gerald Peters Gallery from Jan. 13 to Feb. 11, 2011.

J. Henry Fair’s work has been showcased internationally in museums and galleries, including Mass MoCA, Jerusalem’s Museum on the Seam, and Gerald Peters Gallery in New York. His environmental work has been featured in Harper’s, National Geographic, Discover, New York Magazine, and the Boston Globe, as well as a segment on NBC’s Today Show. Fair’s work is represented in New York City and Santa Fe exclusively by Gerald Peters Gallery.

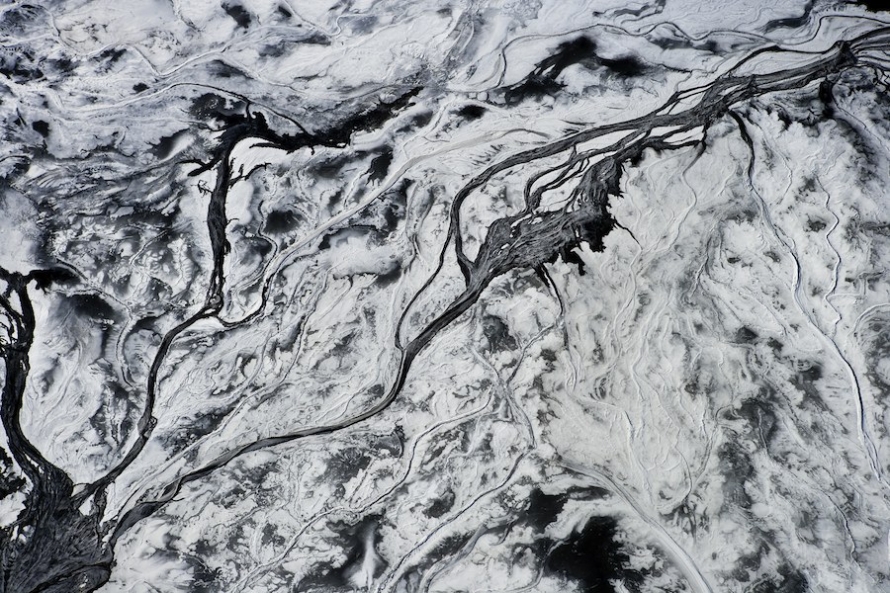

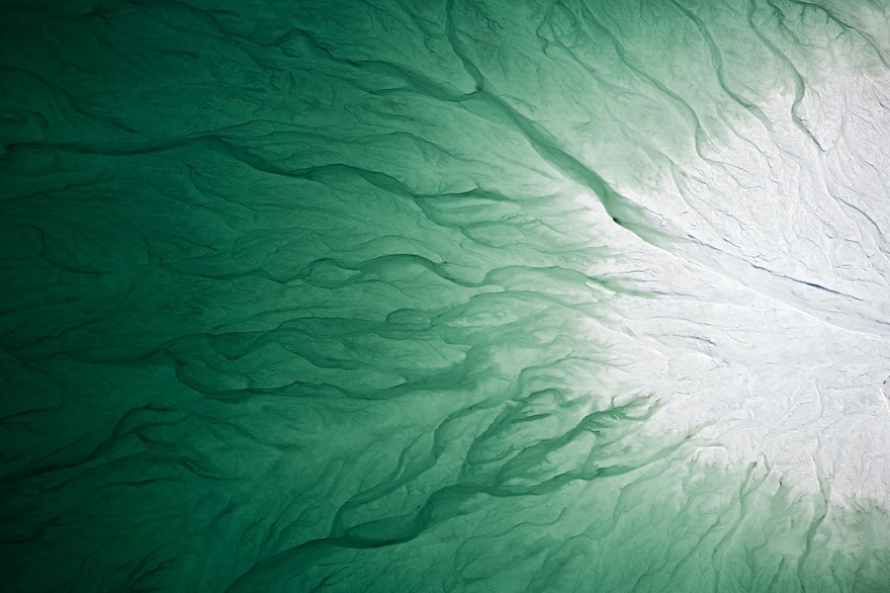

What’s happening in these photographs? These are ongoing environmental nightmares that are a result of our consumer society. The pictures fall into two groups. The first group are the beautiful abstracts that really grab people and draw them in and make them question what it is they’re seeing and hopefully lead them to some understanding of their complicity—’cause we’re all complicit. The brand of toilet paper you buy determines whether or not wolves and bears will have habitats in northern Canada in the next century. We’re separated from that knowledge in consumer society because, of course, producers don’t really want you to think that way.

The second group of photographs depicts the mechanics of the destruction we’re reaping. It includes the more graphic images, like the machines eating the earth and oil rigs drilling in the Gulf of Mexico.

The facts are staggering. If you throw away one aluminum can you’ve wasted enough electricity to power your computer for three hours. You walk by a garbage can in New York City and it’s full of aluminum cans. What that means is mercury is in your fish because aluminum is an electricity-hungry industry, and electricity is made by burning coal, and burning coal is how mercury gets into our streams, which gets into our fish and then into our bodies. That’s the circle I’m trying to illuminate for viewers.

The images in this book are of devastation, but they’re undeniably beautiful. As you say in the intro, “Because of the subject the pictures are inherently political, but my first goal was to create compelling images.” Why create such compelling images?

I think what the human being wants more than anything is entertainment. We’ve all seen too many pictures of denuded hillsides, the usual environmental picture—it doesn’t stimulate any response. Really compelling images of these issues stop people and make them ask questions and get interested. It motivates them to think about the issues in a way that less beautiful images that don’t compel that response.

So there’s political or social power in beautiful objects?

As an artist, one wants to make art that’s as compelling as possible. Photography is very much an arbitrary art on some level. Where we point the camera defines what the image is. Ninety-nine percent of my images are full-frame images. What I shoot is what I print. I’m an old-school photographer in that way.

I’m an artist first, then an activist, because that’s the way I think of myself. But certainly because of the very strange world that we live in, this body of work is very political. Look at the headlines: The Republicans are trying to roll back very small gains in environmental legislation. Ultimately, these issues are not political at all. What’s political about clean air and clean water? But there’s a cadre of elected representatives who are trying to roll back the laws. Because of the political world we live in, my work is political, but it shouldn’t be.

Can environmental destruction be said to have an aesthetic or is it just photographing realities?

There’s certainly a history—the history of photography is filled with people who have photographed industrial objects. In a way they are the pinnacles of human achievement. As horrible as an offshore drill rig is, have you ever looked closely at one? It’s a thing of beauty. Photography is replete with people who have taken industrial objects as subject matter. The Bauhaus has that elevation of function into artwork. The Beckers, German photographers, are also doing it. But my work is much more abstract than others in the same realm. The other thing I’m doing is correlating this tremendous amount of data. I recently went on a flight up the Mississippi, it’s one of my favorite stomping grounds—cancer alley—and for each of the sites I photograph I correlate the E.P.A. release data. So if I find out that a power plant is releasing 150 pounds of mercury, which is about average for a coal-fired power plant, then I correlate that to, “What does mercury do to the human body?” I associate all of the data and current events with the pictures.

In the intro to your book you state that your goal is to promote an activist consumerism. But considering the scale and government support for harmful industrial production, is that going to be enough?

It might not be enough, but it’s all we have. Let’s face it, government no longer responds to citizens, if it ever did. Our government has gotten into this very strange place where it responds to the hand that feeds it, i.e. the producers. As a concerned citizen, what can you do? You can vote, but as a New Yorker your vote for the president doesn’t count. Basically the only vote you have is how you spend your dollar.

Look at how fast producers respond to the buying power of the consumer. Remember when the Toyota Prius came out in 2001, everybody laughed. By 2003 they were rushing to buy the technology from Toyota. People rushed to buy the car because they wanted to invest in a technological innovation for environmental advantage. Wal-Mart now has organic food. If you’ve read Michael Pollan, you know organic [food] is still factory farmed but it’s better than non-organic. The fact that Wal-Mart has it is an indication that people want it and an indication of how fast a retail plant will respond to its consumers. The dollar is the only vote we have.

How do you set up these photo shoots and decide where to take pictures?

I’m fascinated by rivers and their place in our culture. The first place I started was “Cancer Alley” on the Mississippi. I’d been prowling around refineries for years, but especially after 9/11, don’t even bother, they’ll arrest you for standing on the street. I saw cooling towers on a commercial red-eye flight one morning and I took a picture out the window and I thought, “That’s the answer, just get above it.” I started going to an area—in this case the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans—and hiring a plane. I came back with these images and then it became a detective job to discover what the hell I’d taken pictures of. Now, more and more, I’m looking for something in particular. For instance, the regulation of coal ash is a big political and environmental issue now. I got SouthWings, a group of environmentally-minded pilots, to fly me so I could photograph all of the coal plants in Tennessee and focus on their coal ash handling and then made a presentation at the E.P.A. hearing in Knoxville, Tenn., on coal ash.

Who are these pilots you fly with?

Initially, I’d find out where I wanted to go and then find a plane to charter—usually through a flight school. As my reputation has grown, there are two groups of pilots in the U.S. who fly environmentalists. They are SouthWings and LightHawk. They are independent pilots who have banded together in the groups and they fly environmentalists and legislators to show them these issues—coal ash, hydro-fracking, mountaintop removal. They work together and take different regions.

Flying is a huge expenditure of fossil fuels. Is the information you’re gathering worth the waste?

Yes. I use the example of the wolf center I run. We have wolves in captivity—nobody wants to see wolves in captivity—but the reason we have them is so that we can teach people about wolves and about saving their habitat so that we can preserve wolves in the wild. I don’t really believe in carbon offsets and I just think that we need to reduce our carbon footprint. I do it every way I can. I hitchhike! Why should I drive to the train station? Why not hitchhike? You come to my house at night you won’t find any lights on, there’s one light on in one room. I’m no saint—I’m just more and more aware of all this connectivity.