During the past 40 years, writer and photographer Danny Lyon has recorded the stories of “outlaw bikers” and documented the front lines of the Civil Rights movement, but most of the photos in his book Like a Thief’s Dream aren’t his own. To accompany the story of his friendship with James Ray Renton and Harold Davey “Dinker” Cassell, two men convicted of murder in Arkansas, Lyon included mug shots, scrapbook pages, even a “Wanted” poster from the FBI. In the tradition of Wallace Stevens, these “found” photos represent Cassell and Renton better than any high-resolution photojournalism ever could. The photographs, Lyon’s book, and this interview depict the complex and politically urgent issues that American prisons raise and the ordinarily faceless lives spent within these institutions.

Danny Lyon was born in Brooklyn. While studying history at the University of Chicago, Lyon joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee as their first staff photographer. One of the best-known photojournalists today, Lyon has produced 11 books of photography and 12 nonfiction films. His books include Indian Nations (Twin Palms, 2002), Knave of Hearts (Twin Palms, 1999), a memoir, Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement (University of North Carolina, 1992), Merci Gonaives (Bleak Beauty, 1988), an account of the 1986 Haitian revolution, and Conversations With the Dead (Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1970), the first book by a photojournalist inside the American prison system. Lyon recently republished his second book, the acclaimed The Destruction of Lower Manhattan, with powerHouse Books. He has received a Rockefeller Fellowship in filmmaking, Guggenheim fellowships for photography and filmmaking, and numerous fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts. His photographs are in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Art Institute of Chicago; the Corcoran Gallery of Art and the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; as well as other museums throughout the world. Lyon lives in Ulster County, N.Y., and Sandoval County, N.M.

How did you meet James Renton?

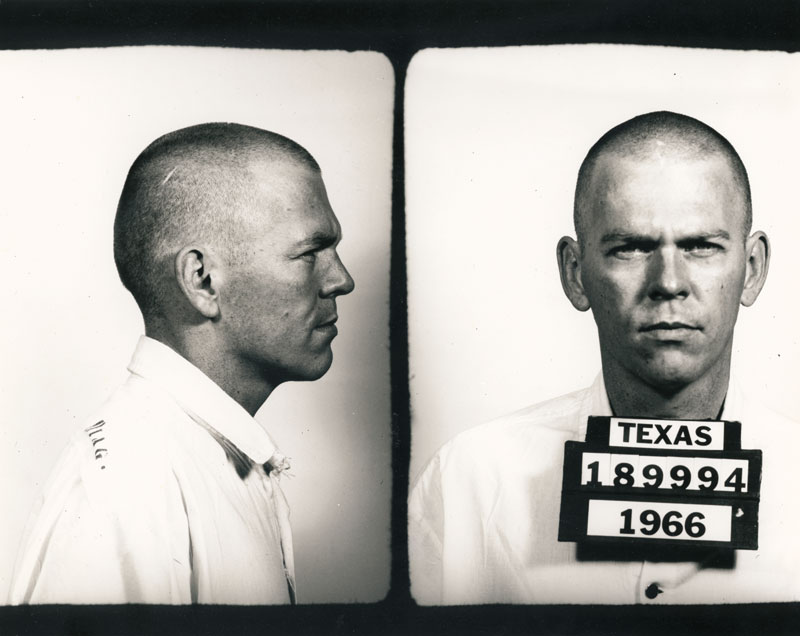

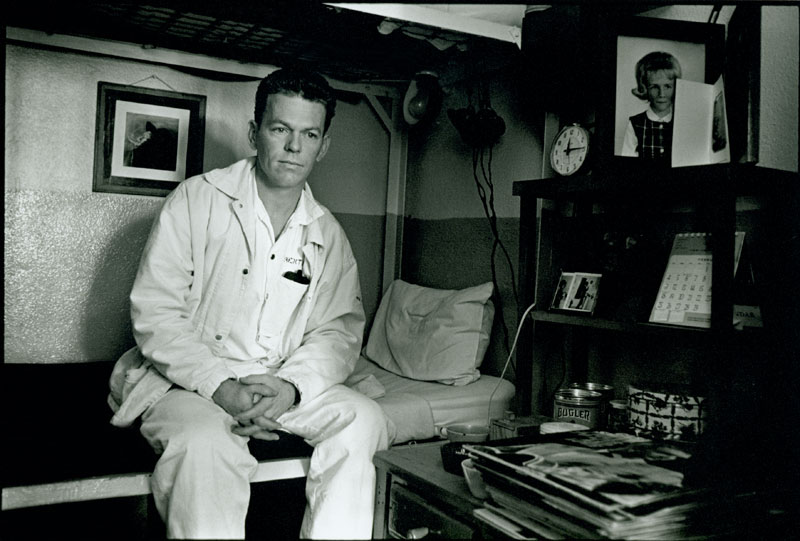

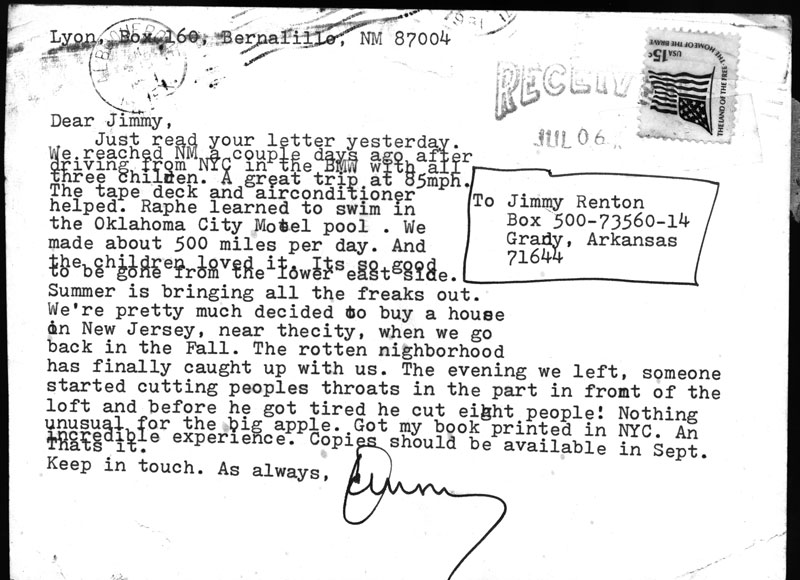

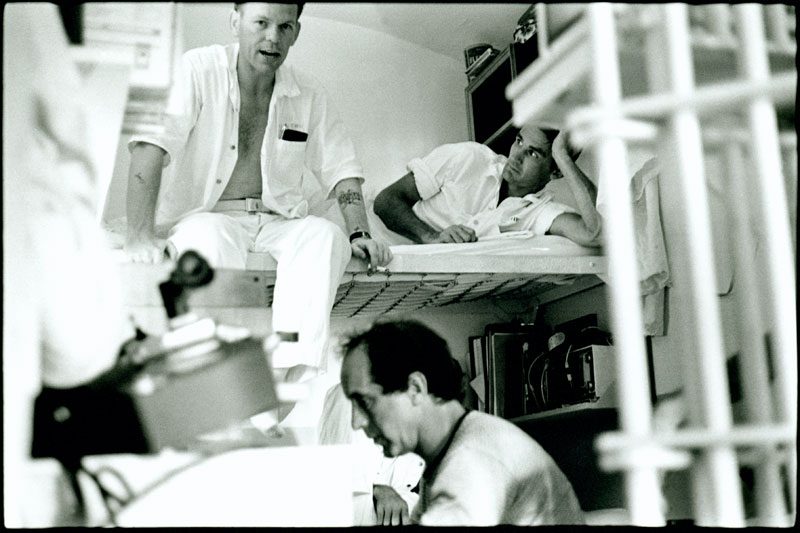

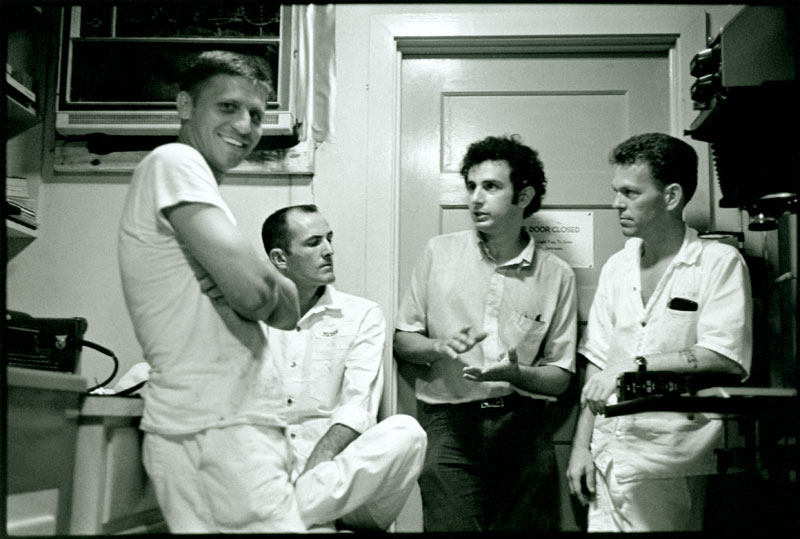

I met Renton walking down a cellblock in the Walls prison of the Texas Department of Corrections. He was interested in my Nikon F, and asked to use it. We made pictures of each other. He had been trained as a lithographer in El Reno, a federal penitentiary in Oklahoma. Renton was then working in the Walls darkroom. From there I started to visit him in the print shop and the darkroom. Towards the end of my stay I was “borrowing” documents from the T.D.C. record room, walking over to the Walls prison darkroom, and having Renton make copy negatives of them, which I would later use in my book, Conversations With the Dead. He was interested in offset printing and the production of my books.

Why was Renton in prison?

When we met, he was doing 11 years for the burglary of a drugstore in Port Arthur, Texas. He was released in 1969 while I was still working in the prison. I believe his time in El Reno, as a kid, was for counterfeiting. He made a very authentic copy of a Canadian bond worth a few hundred thousand dollars. He was very proud of it.

Around 10 years after you met, Renton was convicted of murdering police officer John Hussey. How do you feel about Renton’s accused crimes?

There is no question that Renton was guilty of murdering Officer Hussey. He did not use the weapon, but he was there, and is equally guilty under the law of what was an execution-murder. During his lifetime I was never able to bring myself to look him in the eye and ask him, “What happened that night?”—something I came to regret. When you know criminals, it is not polite to ask too many questions about their crimes. At the time of his trial, when the prosecutor was portraying Renton as a monster, and Officer Hussey as his innocent victim, Renton turned to me and said, “He wasn’t innocent. He was a soldier in an army.” Later in prison he told friends that the kidnapping and murder were “just a dumb mistake.”

How do you understand your role in this story? Are you documentarian, friend, activist, journalist?

The story evolved organically, which is how almost all of my work is done. It began with me as a journalist and bookmaker inside a prison. Later it became a friendship. Then when he made the Ten Most Wanted List, I was moved as a journalist and documentarian to pursue the story. I’ve never separated what we call “friendship” from my work. I like the people I work with, and I prefer to work among my friends.

What was Dinker Cassell’s relationship to Renton? How did you become friends with Cassell?

Cassell was a professional burglar when, after leaving the Kansas prison, he was introduced to Renton. But Renton was a much more violent and aggressive criminal than Dinker. They traveled together and committed burglaries. During one of these burglary trips, into Arkansas, they parted company. That night Renton and a buddy kidnapped and murdered Officer Hussey. Dinker was hunted down, and captured, and asked to testify against Renton, “to put Renton in the electric chair.” When Dinker refused to cooperate with police, he was charged and convicted of the murder also. In the process of writing about Renton, I looked up Dinker in prison. He is a very intelligent and charming person. Over the years it took to write the book we have become friends. He also helped me make a short film called Murderers.

What is the status of Dinker’s case today?

Harold Davey Cassell, aka Dinker, has spent 30 years in prison in Arkansas primarily because he refused to testify against Renton. He is currently filing an appeal in Pine Bluff, in the Arkansas state system. Eventually it will reach the Arkansas Supreme Court. It is his last chance to make an appeal. Publicity, especially inside Arkansas, is the best thing that can happen for him at this moment. He has had almost none.

What are some of the most important things you learned about the American prison system through photographing there and through the friendships you made?

You really need a friend, or family member inside a prison, to appreciate what we are doing. America has two million people inside of her prisons. Only China, a dictatorship, tops us in this growth industry. I like to think of the words of Fredrick Douglas “Be neither a slave nor a master.” All of us, outside of prisons, are the masters.

What do readers and audiences who have limited experience with the prison industrial complex need to understand about these institutions?

They need to understand that they should be turned into bowling alleys, schools, and daycare centers, or demolished. We could probably do better with 90 percent of the inmates being released. Communities should deal with offenders on a local level. Review panels should meet with all of the 200,000 prisoners doing life sentences. Many of these people are harmless and aged, and should be released. I would like to see review panels sent into all the prisons, to meet with inmates face to face. Most should be released.

Can you describe some of the changes in American prisons and the American prison system since you starting photographing and visiting prisons and corresponding with men in prison?

When I was working in the Texas prison there were 12,500 men and women inside the prison and there were no executions. Today there are 200,000 in Texas and they kill prisoners all the time. Prisons are now everywhere, a major employer in upstate New York. Simply put, everything about prison is worse.

How can we, as a society and as individuals, change our policies and values in order to accept and respect someone despite some of his or her actions?

The best way to change yourself is to go outside your world into the world of others. It’s a big world out there. The worst thing about New York City is that all the young people that gather there are extremely like-minded. Creative people are comfortable there, but they are preaching to the choir. I always wanted to move Brooklyn to Missouri. Everyone would benefit.

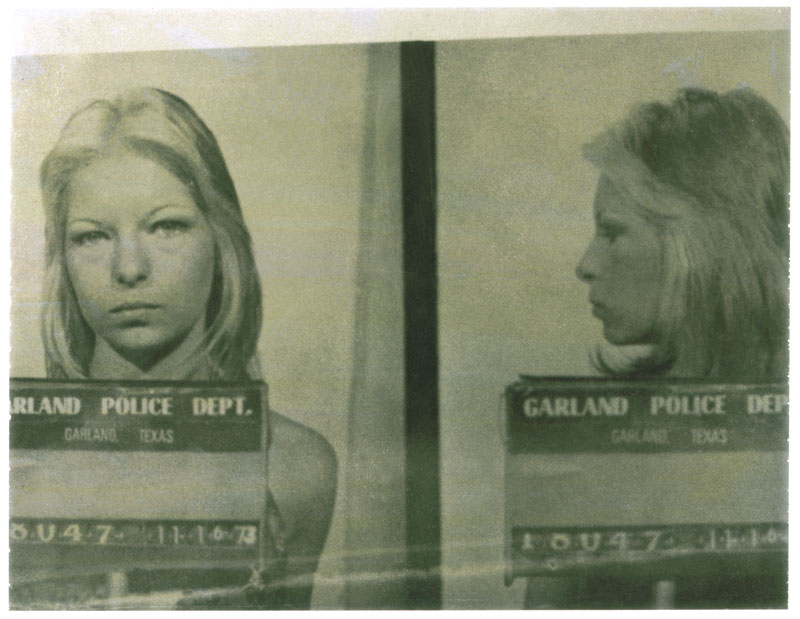

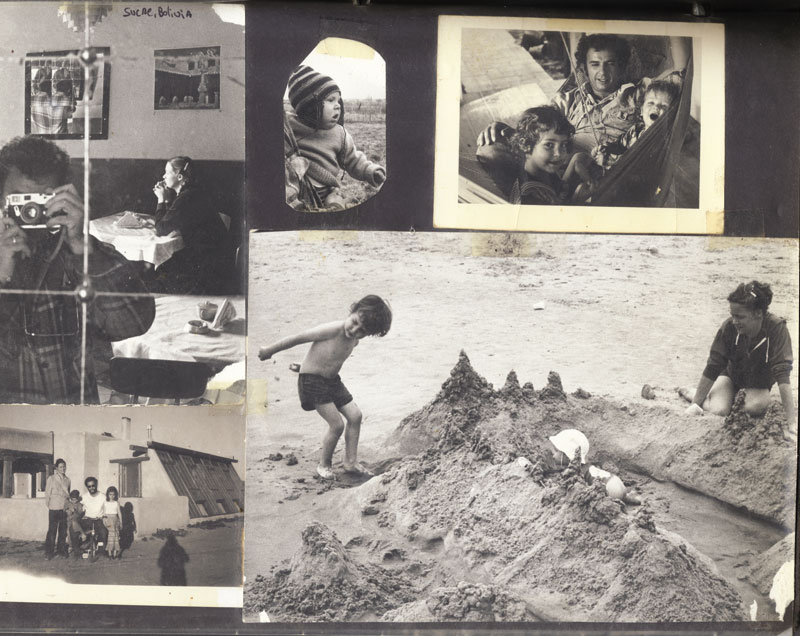

You’ve mentioned Walker Evans and the idea of finding a picture rather than making one, in respect to the images in Like a Thief’s Dream. How do the photos from this book give us more of a sense of Renton or Dinker than your own portraits or photojournalism?

Walker Evans worked in Cuba and found pictures in a police file of murdered students. Clearly they were better than anything he could do, and he published them. It’s true that when you find a picture, you tend to get possessive of it, and feel its yours. I’ve always been fond of mug shots, particularly of friends of mine. I published many of them in Conversations with the Dead. For Thief’s Dream finding a picture of Dinker 30 years before I knew him was very exciting. A yellowing Polaroid mug shot of young Dinker with streaks on it, to me was very beautiful. He looked like one of the Everly Brothers. I put it on the back cover.

Gallery

Like a Thief’s Dream

Read artist interview