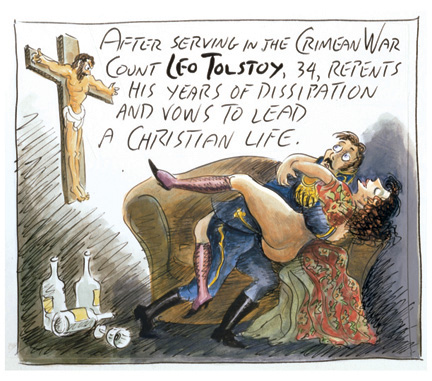

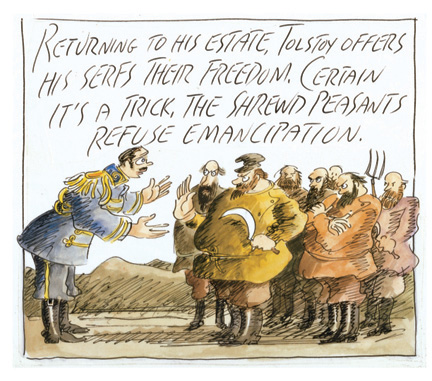

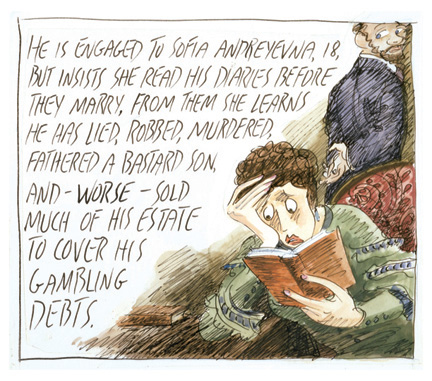

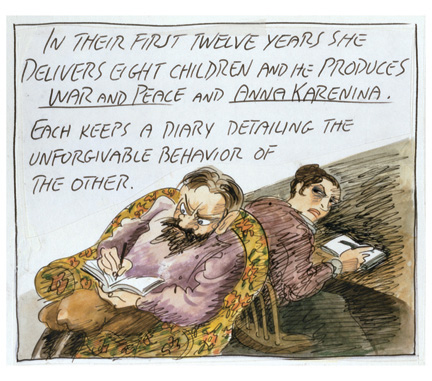

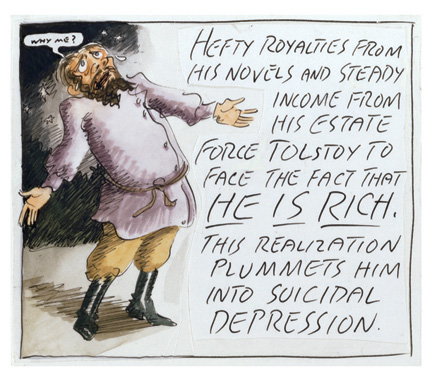

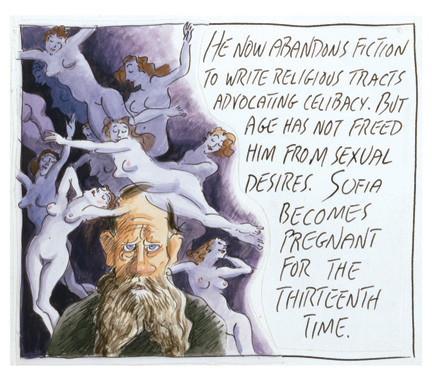

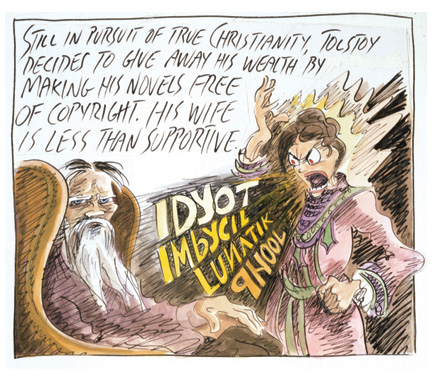

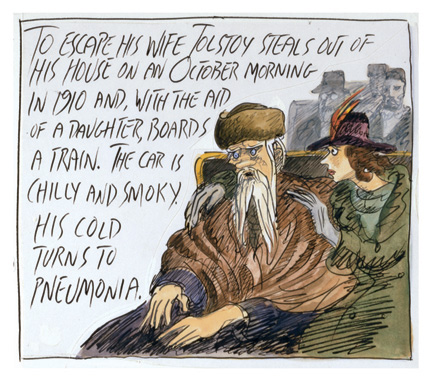

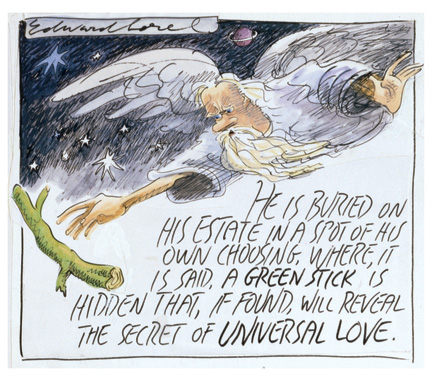

Since the 1960s, illustrator Edward Sorel has massacred political leaders and public personalities with his shrewd cartoons and caricatures. In his new book Literary Lives (Bloomsbury, originally serialized in the Atlantic Monthly), the Atlantic and New Yorker contributor mercilessly scrutinizes the lives of nine canonized authors, a scathing intrusion of humor and satire into snooty literary history.

Nicole Pasulka: Much of your published work in the Nation, the New Yorker, and the Atlantic Monthly focuses on politics and current events—why were you drawn to work with historical biography for this series?

Edward Sorel: I find that when I have shows or exhibits, the political work I did two or three years ago is so dated that I can’t even show it. I got tired of politics; it was too ephemeral. So, I had the idea of doing something historical—history stays still as opposed to the present, which is always moving around.

NP: What texts or images did you use as starting points for Literary Lives?

ES: When I was in school there used to be something called Classic Comics. They were bowdlerized biographies of the great men. They were kind of boring, and suddenly it seemed funny if we could do the same kind of thing, but not leave out all the unpleasantness—instead, bring it out.

NP: After reading your book, many of these authors seem so nasty. Were they actually this bad, or are the cartoons an exaggeration?

ES: Well, they weren’t all bad. Tolstoy wasn’t bad; he was just odd and kind of crazy. But some of the others were nasty. [Lillian] Hellman was nasty and Bertolt Brecht was one of the 10 worst people in the whole world, I’d say. And so was Carl Jung. I was not too fond of Sartre. No, they were nasty pieces of work. The first writer I [profiled] was Balzac and it wasn’t funny. Balzac was essentially a very sympathetic character because he was shunted off during his childhood by his mother and was always looking for his mother’s approval. The cartoon was very sad and wasn’t successful. The next writer I illustrated was Tolstoy, and I realized that they would have to be nasty in some respects to be amusing.

NP: Why emphasize the ugliness in these writers’ lives?

ES: I have nothing else in mind, as far as I know, other than to make people smile. And avarice, duplicity, and selfishness can be amusing. Vices are amusing, and these were all writers with vices.

NP: How is it that such great authors can turn out to be these cruel, hypocritical individuals?

ES: When you read biographies, it’s very disappointing; you see that when writers or artists receive a certain kind of fame they seem to think of themselves as godlike and they change a lot. It’s surprising how many people were big fans of Mussolini—Yeats was one, George Bernard Shaw was another; there were dozens. I think that’s because they no longer felt an affinity with the democratic process. They had an affinity with strong men. I was always very distrustful of ideologues.

NP: This distrust is apparent in your political cartooning, as well.

ES: I’ve always had distrust for all authority. [My political cartooning is] telling truth to power, in a sense. It’s bringing down the gods. [laughs] There’s probably some deep psychological need I have in tearing down people who are more famous and better artists than I am.

NP: Do you see a difference in an audience’s response to images versus written commentary or criticism?

ES: One of the reasons why the op-ed page these days has words but not pictures is because pictures do have a power that words don’t have. The newspapers are very frightened of them, as witnessed the recent business about the [Danish newspaper’s] cartoon [of Muhammad].

Gallery

Literary Lives

Read artist interview