Even if you’ve never heard his name, chances are you’ve seen Shepard Fairey’s stickers, posters, and stencils on lampposts in New York City, or peeking out from doorways and street signs in one of the countless countries where his street art has traveled. With a large-scale installation at Jonathan Levine in New York City, Fairey brings his sense of humor and outrage to his gallery work. Born in Charleston, SC in 1970, Shepard Fairey lives and works in Los Angeles.

All images courtesy Shepard Fairey, Kyle Oldoerp, and Jonathan Levine; all images copyright ©, all rights reserved.

Your work has always struck me as having a political bent or message. Do you feel like the message has changed over time?

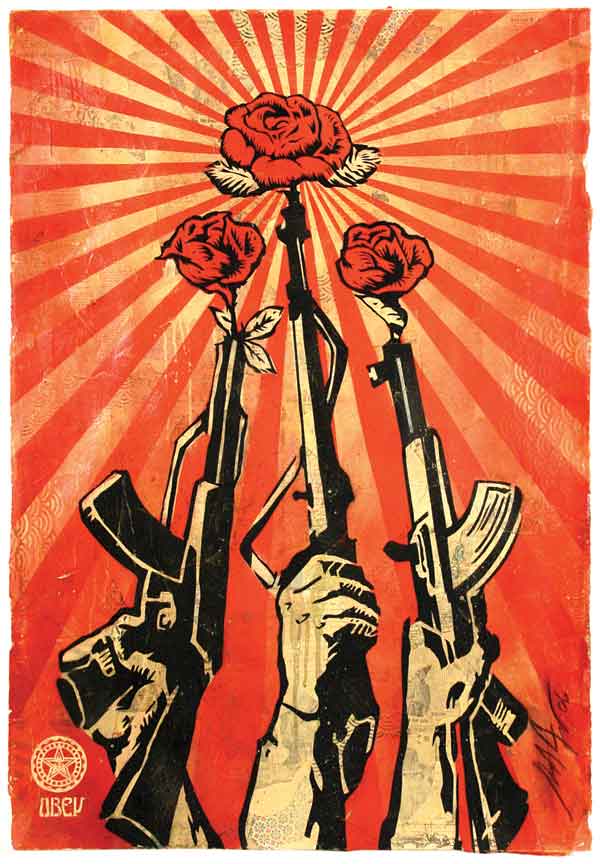

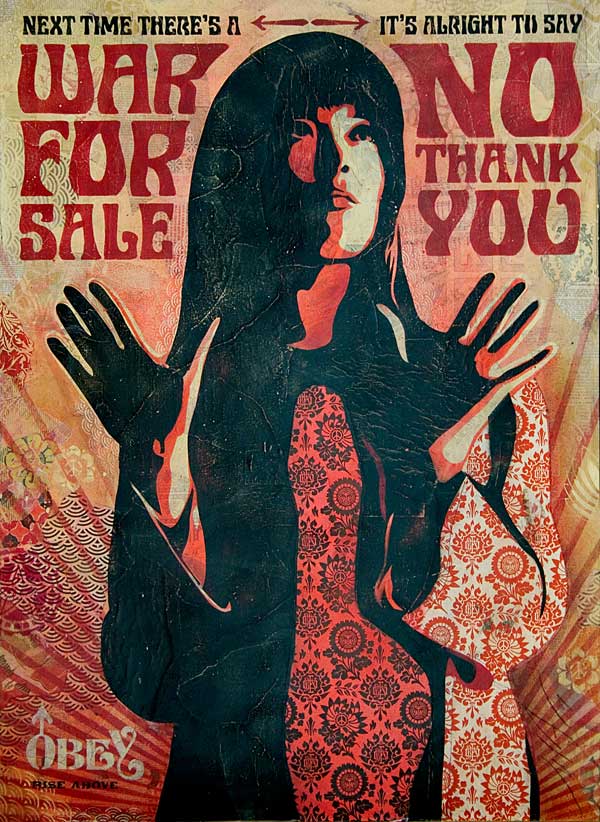

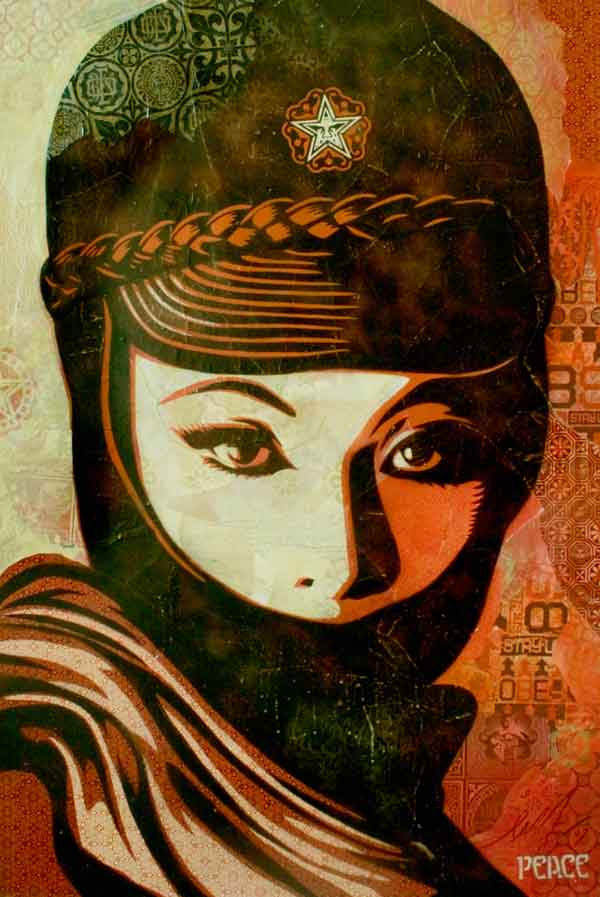

The work’s been evolving slowly but surely for 18 years. Especially since the war started, I’ve been doing stuff that’s more overtly political. Prior to that, I’d been doing images that were about questioning authority and the pervasiveness of advertising. But, especially since Bush has been in office and [since the] post-9/11 buildup to the war, I felt that there weren’t enough dissenting voices, so I started including direct political commentary in my work.

What specifically have you been trying to say with your more recent work?

A couple of years ago my wife and I had a daughter, and I began to look at what was failing about my critique of the war. I think that it was a hostile, divisive critique. So in addition to being angry and critiquing the war, I started to turn out some work that was promoting peace. [That basically said,] you’re just an asshole if you can’t get behind [an idea of peace].

In some cases thoughtful anti-war messages can be more sophisticated than a very anti-capitalist critique.

This body of work specifically is sort of a satire of the Norman Rockwell naïve American dream. The pursuit of abstract American ideals has led people to support whatever the government says is in their best interest—which often isn’t [in their best interest]. Whether it’s the little girl holding the grenade or the couple hugging the bomb, there’s stuff in there that uses the language of Americana. But it’s also mixed with the color palette and some stylistic elements of my earlier work. It’s a mixing of several different styles.

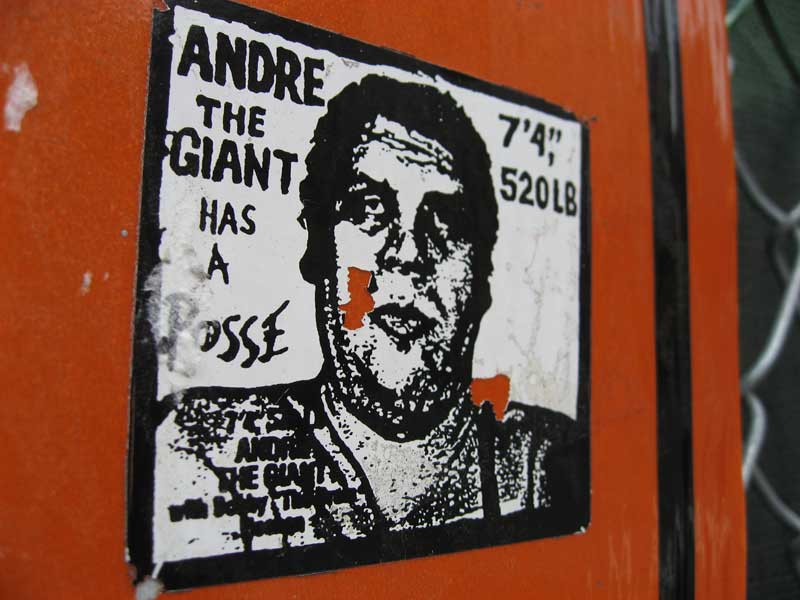

I think a lot of people are familiar with your work because of Obey Giant and the Andre the Giant sticker. How has that image affected or reflected your career?

The original Andre sticker started as an inside joke among friends. As it [gained] a cult following, it opened my eyes to a lot of sociological phenomena about control of public space, psychology, paranoia about cults. There’s a Rorschach test-like quality of an image that has no correct interpretation and that elicits a different interpretation from each individual. I first hijacked a lot of pop culture stuff like putting Andre’s face on the first Neil Armstrong moonwalk, or [on] Jimi Hendrix’s afro. I was being a style chameleon and piggybacking on things that had already happened. As I saw a more serious side to its implications, I started using the “Obey” and taking it in more of a cautionary, “big brother is watching you” direction and utilizing a lot of the communist propaganda because I knew people had a built-in fear of that aesthetic [due to] the historical context.

How did you come to make the Andre sticker?

I ran a skate shop as a college student at RISD and I had a friend come in one night [as] I was making t-shirts. He said, “I want to learn how to make a stencil while you’re doing that.” So I looked in the paper and found a picture of Andre the Giant and he said, “No way. That’s stupid.” At the skate shop it was really cliquish and everyone who hung out at the shop was like a little gang. We were all trying to show each other and everyone else up and I thought it was kind of silly. So, very spontaneously, we started an inside joke. I latched onto the idea for whatever reason. It was absurd because we were mixing wrestling, which to us was the lowest common denominator, with skateboarding, which we saw as totally cutting-edge culture. It stuck with our community: it played into that elitist mentality but at the same time it was perpetuating something so ridiculous. There’s an element of that to the project to this day.

I think people really get excited when something pervasive, iconic, and successful is spontaneously born.

I think it almost has to be spontaneously born because when you’re going to art school and all your teachers and peers are super-critical of everything you’re doing, if you set out to create what would be the central image of your work for the next 15 years you would be paralyzed.

Once the sticker started having a wide presence, did its purpose change?

Initially, I was more or less anonymous. I just hoped that this would be the first domino to fall, for people to start questioning all commands, whether it’s to buy, or obey the law, or anything pushed their way. As I became known as “that guy,” I felt the need to evolve. Now that I had people’s attention, instead of being ambiguous and enigmatic and hoping it creates the kind of dialogue I want it to create, I’ve used it to say things I wanted to say.

You’re known for having an anti-establishment message. Do you get shit for being a “street artist” and doing corporate design work?

Of course I do. People will give you shit for almost anything besides crucifying yourself. People say, “Oh, he did this street art thing and now he’s just cashing in on it.” I couldn’t survive from art until about three years ago. I had to do graphic design because I couldn’t make a living until very recently. I always felt that graphic design was a good way to continue honing my art skills and make a living creatively. You can call someone a sellout if they do graphics for a company they don’t ethically agree with [solely] for the money. I’ve turned down jobs for companies when I’m not comfortable with they’re doing.

What kinds of design work are you doing?

I just did the new Smashing Pumpkins album cover. I’ve done stuff for Interpol, for Billy Idol. I’ve done stuff for Toyota and I did the Walk the Line movie poster. I think it’s really horrible when people vilify artists who have design careers as if they’re working with the enemy or something, and these are people who are wearing limited-edition Nikes. Most of these projects are things I want to do because I’m excited about the subject matter. The others, I definitely don’t have a problem with. I get to be more selective now.

Do you still do street art?

When I was in New York I did a bunch of stuff on the street and when I was in Japan a few months ago I did a bunch of work there. I’m putting stickers up every day all day. I did [a] bunch of oversized posters in New York.

How is it related to what you show in galleries?

The only difference [in the art being shown] in the gallery is that it’s a controlled presentation. I can spend more time on the stuff and know that it’s not going to get splashed or buffed or gone over by another graffiti artist or ripped within a matter of days. On the street, the goal is to make it as artistic as possible, keeping in mind that it’s temporary. I’ve developed technology to put up stuff that works on the street: really strong, fast to put up, and not that expensive for me to create. The thing that’s discouraging for street artists is when they spend five hours on a piece and it’s cleaned two days later. There’s not a lot of return on the investment. I made sure that the stuff that I make communicates what I want it to communicate but is fairly efficient. It’s finding a balance between quantity and quality.