Small details make a space unique, familiar, and alive. Photographer Dave Jordano knows that a personal, individual spirit can bring a place to life, and, in his “Article of Faith” series, he shows us it’s not only how, but where congregations pray that defines their faith.

Dave Jordano was born in 1948 in Detroit. His work is included in the permanent collection of The Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. His recently completed book, Articles of Faith, was published by The Center for American Places at Columbia College, Chicago. He lives and works in Chicago. All images courtesy courtesy of the artist, all rights reserved.

How do you understand the role of the storefront church in Chicago?

Their first role is to provide a haven for those who want or need a place to practice their faith. Secondly, their physically small size creates a sense of connection and closeness that is unique amongst parishioners and their association with a particular pastor. Many small community churches are akin to private social clubs, where group membership is often less than 15 or 20. This kind of close-knit association is the attraction for many members who seek out pastors because of their personality and preaching style. I’ve seen three churches on one city block, each a different Christian denomination, each with a pastor preaching in his or her own distinctive style. It’s this diversity of faith and the eccentric characteristics of each pastor that creates such a proliferation of storefront churches.

Do you feel that the churches are changing?

I don’t see things changing much. There is a long history of small storefront churches in urban areas throughout America. The great migration of African-Americans to the north during the last century has definitely contributed to this. Even after blacks moved north, they still encountered much racial tension and segregation, creating isolation and economic hardship within their communities. Because of this, many groups couldn’t afford to build a large church, so the idea of reusing small empty storefronts in depressed areas where rents were low became the catalyst for their reuse. It’s a cultural phenomenon that still resonates today and has become a vital component within the cultural fabric of poor black urban communities. Interestingly, whenever I would enter a middle class black neighborhood, I noticed that all the storefront churches would disappear, being replaced by more affluent, traditional, larger congregational churches. It’s true that the poorer the neighborhood, the higher the concentration of storefront churches.

What’s your connection to these storefront churches?

Other than being raised Baptist and my parents both being born-again Christians, who were very active in their church, I really have no connection. I guess there was a sense of sharing a common knowledge when speaking with the pastors and their members. As a self-employed freelance photographer, I related to the independent, strong-willed spirit that drove these pastors to chart their own religious path out of desire and compassion.

Why photograph them?

The idea came about quite by accident. I was working on another project just over the Illinois-Indiana border and my route took me over the Chicago Skyway Bridge. I would often look down onto a small plain industrial building that had a large hand-painted sign above its door that read, “Cathedral of Divine Love Church.” It impressed me that this pastor felt this little nondescript building was worthy of being called a cathedral. I decided to stop and introduce myself and ask the pastor if I could photograph the church empty. I told him I was mainly interested in how he had decorated and set it up. This threw up a cloud of suspicion. I persisted, and after much discussion about my intentions, God, and religion, he granted me permission. I felt as if I had been the center of an inquisition, but rightly so. It was important that I had the trust of every pastor, that they knew my intentions were sincere, and that I had a great deal of respect for their church. I went back several times over the next month and made more photographs. In total, I worked on the project for three and a half years and photographed 65 churches.

What’s the reason for photographing the churches (mostly) empty?

I think that an interior space can possess a personality all its own. How a pastor adorns and decorates a space reflects on their religious ideology, their concept of what is appealing and attractive to others, and how that space can make others feel comfortable and leave them with a sense of feeling important. I also wanted to document these spaces not only for their unique qualities but also because of their positive influence within poor black neighborhoods as pillars of community stability and support, especially where crime, prostitution, and drugs are often just a step outside the front door.

Did you have a favorite church of the places you photographed?

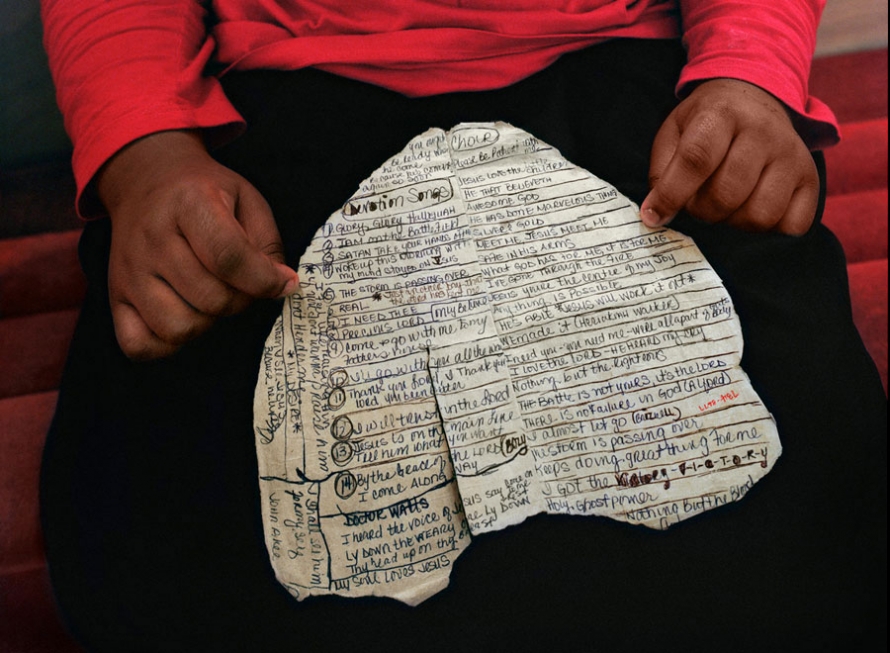

One picture in particular is of Pastor Mallet’s back room. It has dozens and dozens of hand-written posters covering the walls. Some of them went back nearly 40 years. He saved them all and created a little shrine that represented his own beliefs. He was just an amazing person. I loved his eccentricity and his determination. He passed away last year at the age of 92. Really though, the project is seen as a collective whole, where all the images build a narrative that evokes the feeling of the place and enriches our understanding of a complex and distinctly American culture.

Your photos seem to really hone in on small details or particulars in the churches, but seen in a group, the pictures give the sense of a rich and complex whole—are they portraits of these places, in some way?

Yes, I see these rooms as “portraits” that resonate with the creators’ personality. Insignificant items like the ripped and folded-up paper song sheet that the young girl is holding so delicately between her fingers are important documents that signify identity. The hand-written titles are someone’s favorite songs to sing. It’s just a piece of paper, but its history is profound. Many churches display portraits of the founder of that church, to pay tribute or memorialize them—some were photographs, some were paintings on the walls. What I found interesting was that there were often more portraits of the founding pastors on the walls than there were of Christ. I took this as a sign of respect but also as a testament to the importance of the here and now and the day-to-day guiding principles of the leader of the church.

You mentioned you’re working in rural Illinois right now—what are you photographing?

Small towns specifically. To paraphrase my artist statement: “Illinois is a state long monopolized by mechanized agricultural farming, creating endless fields of corn and soybeans and leaving several hundred economically challenged older small towns dotting the landscape. Within this geographic and economic framework I’m searching for strong notions of individualistic expression that are tied directly to the land and its people. As someone who is admittedly an outsider, I’m trying to discover for myself the differences that separate my own perception of rural life and what I find to be that reality, whether real or imagined.”

Much like the church project in its relationship and connection to Chicago, Illinois’s small rural towns make up a part of the economic and social fabric of the state that gives it its character.