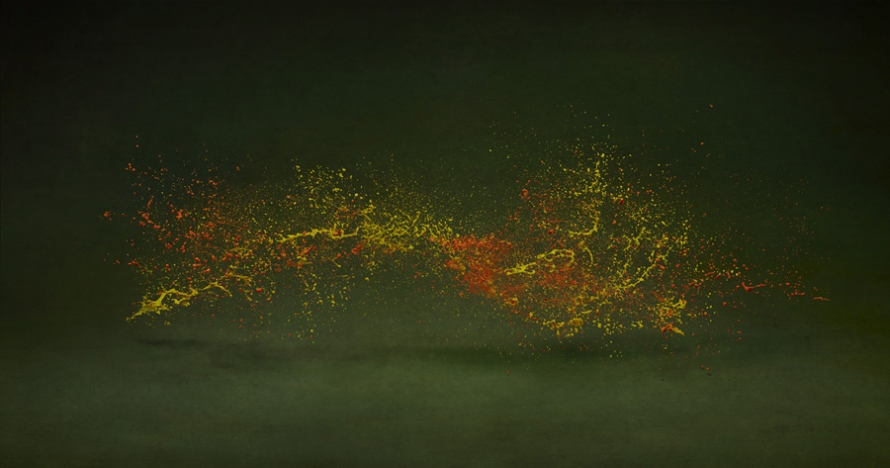

In Shinchi Maruyama’s photographs, handfuls of water tossed into the air become flowerbeds or perfect cylinders. An amalgam of sculpture, performance, and photography, Mauyama’s work reveals how much beauty can occur in the blink of an eye.

Shinchi Maruyama was born in 1968 in Nagano, Japan. After graduating from Chiba University in 1991, majoring in film and photography, Maruyama began taking photos for his personal project “Into the Spiti Valley,” a documentary work about Tibetan culture in India. The exhibition opened in 2001 along with the publication of two books, Into the Spiti Valley and Spiti. Maruyama moved to New York in 2003 where he created his two latest series, “Nihonga” and “Kusho.”

All images courtesy the artist, all rights reserved, copyright © Shinchi Maruyama.

How does your work as a photographer relate to traditional Japanese painting and calligraphy?

The only art series of mine that has been inspired by Japanese traditional calligraphy is Kusho. As a young student, I often wrote Chinese character in sumi ink. I loved the nervous, precarious feeling of sitting before an empty white paper, the moment just before my brush touched the paper. Those childhood moments have undeniably influenced my work in that series, however, my respect for the Japanese ability to find the beauty in the imperfect (the essence of wabi-sabi) is the main source of inspiration that is found throughout all of my work.

You describe the images in your photographs as water sculptures, how do you make these sculptures?

By my hands and glasses of water.

How do you then document them?

I use a Phase One P45 camera and a Broncolor Strobe to capture them.

These images—or sculptures—are so exciting, fleeting, and unique. How do you determine or control the shape of the water or ink?

Just keep throwing the liquids for the sake of it.

It seems there’s a definitive moment of performance in your work, though this be said of all painting and sculpture. Are you more aware of the event or moment of your sculpture because the final result is a photograph?

I think I am more aware of the moment recently after many years of experimenting with liquids. But no matter how many times I repeat the same process of throwing it in the air, I never achieve the same result. And I am so fascinated by this unexpected interaction of liquids colliding, which happens fairly infrequently, that I am overwhelmed by its beauty.

Was your process for making the Garden images different from that of the Kusho or Water Sculpture images?

Yes. For Garden, I’ve pictured shapes and colors of the liquids in my mind first, and tried to re-create it on the shoot. It is said that a Zen garden represents the minds of high priests who achieved enlightenment. I always attain serenity by just being in a Zen garden. It makes me forget every temptation, evil thought, or news from outside. I’ve tried to represent this feeling I get from Zen gardens in these photographs. Although I am still far from those enlightened monks, my actions—throwing liquids for the sake of it and photographing them over and over endlessly—could be considered spiritual practice to reach enlightenment.