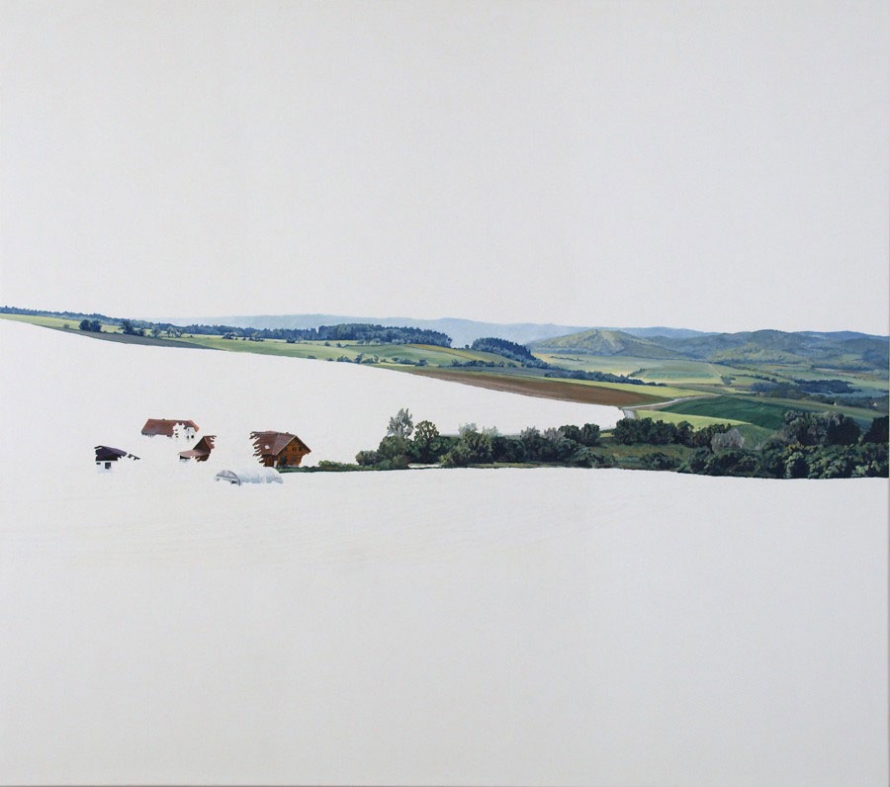

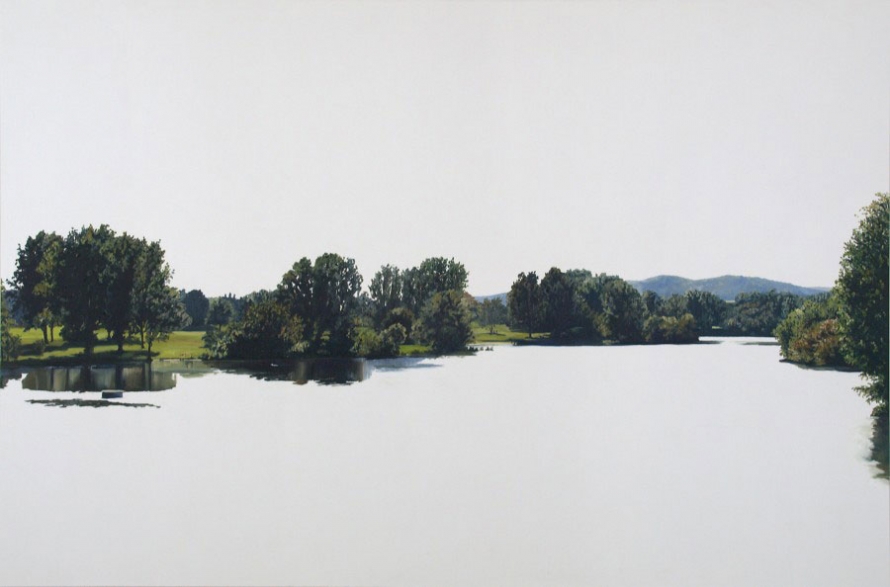

Cézanne couldn’t tell you what an apple looked like, not empirically (who could?), but his paintings shocked audiences by conveying what apples looked like to him. Painter Silke Schöner turns landscapes on their heads with extraction, paving fields and sky with empty plains of space that we can fill in. A new exhibition of Schöner’s work opens this week, May 14, 2009 at Dillon Gallery in New York, and will be on view through June.

Silke Schöner was born in 1968 in Krefeld, Germany. She has worked as an artist in Kassel, Germany since 1989 and has been widely exhibited in Germany, Japan, and the U.S.

How long have you been using white space to isolate aspects of your art? What does it enable you to do as a painter?

After completing my art studies in 1994, I started working with ornaments and shapes. As an experiment, I did some portraits of a very close friend of mine called Sylvia Weiss (White!). The portraits were on a white background with geometric forms as a supporting means.

For me, an object painted in a white space has room to expand, i.e., it is not limited by adjoining objects or visual information. The portraits showed Sylvia in pensive poses, and by means of the geometric elements, I tried to create an abstract/notional impression.

This then led me to attempt painting the abstract/spiritual world by means of real objects. Instead of color-space paintings (associated with emotions), I used empty white spaces to represent the mental/spiritual, whereby the viewer unconsciously adds the “missing information.”

How do you select which parts are the “missing information?”

Basically, it’s purely intuitive or coincidental. However, when making photos of landscapes, I do a kind of pre-selection in my mind. Then, while painting, I decide whether individual details are to remain or not. I compose the picture by painting the most important objects first, and then adding detail by detail until I feel that the painting is finished. Hereby, the formal, the “weight” of each object plays a role. Sometimes I decide to leave out items that seemed to be important when I took the photograph. Also, by deliberate shaping of the positive, real shape, I am able to give a specific negative shape to the white space. In this way, I am able to influence the viewer’s spiritual/mental impression.

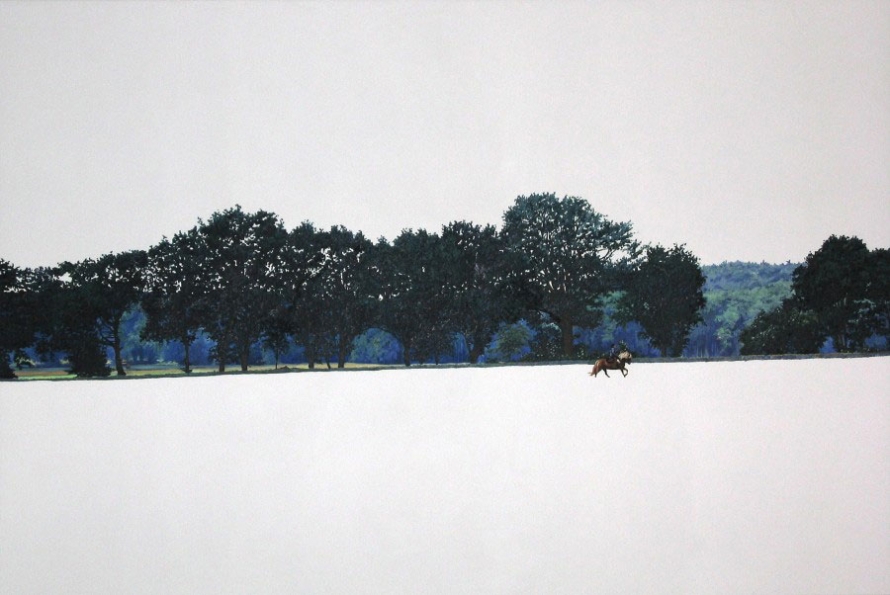

Your recent paintings seem more sparse to me, even lighter than previous years. It’s quite an alien world. Do you want your paintings to have a disorienting effect?

The reduction of the “real” portions of my paintings was a gradual process up to the point where there was no longer a connection with the border of the canvas (see “Sleeping beauty”). With this painting, I realized that I was getting close to surrealistic art, a direction that I did not want to go. By means of photography, I want to remain in the real world, because I believe that it is also possible to represent the spiritual/mental without resorting to surrealism.

Then to remain in the real, is the real world external or internal? Do you see the natural world as something outside you that you are painting, or are you painting a vision that comes from within?

My paintings are based on photographs projected onto the canvas (the natural world). I then paint what I consider to be essential, as explained before. Hereby, I don’t abstract by changing shapes or colors, but instead I select and compose the objects that I intuitively feel are necessary (vision from within). By painting only a portion of the real world together with the white spaces, I create a landscape with a universal character that conveys distance, clarity, and serenity. Viewers associate with the universal impression, and “recognize” a landscape familiar to them.

One piece of work with a special meaning for me is “Winterbild.” Painting the group of people wandering through the cold of winter created an inner picture of flight and expulsion. For me, the painting is charged with the subjects of loss, separation, and homelessness.

In fact, the painting developed such a powerful dynamism of its own that it got lost on its way from Germany to New York. While filling out the search request form, I imagined it was similar to the procedure for tracing a missing person. When I was informed some six months later that the painting had been found, I felt relief and happiness in two ways: first, I was pleased that the picture was safe in the Dillon Gallery, and second, I was able to experience the sense of loss again, but this time with a kind of healing effect.